Our discussion on The Devil’s Vice included comments on: its Gothic elements; references to other Gothic films; Richard’s ‘Gaslighting’ of Susan; the audience’s genre expectations; the audience’s alignment with Susan; Richard and Susan’s relationship in terms of control and isolation and Susan’s realisation that Richard is her abuser; the role of technology; the film’s contemporary setting; the film’s purpose of the promotion of awareness of domestic abuse and the relation of this to the Gothic.

Like last session’s The Diary of Sophronia Winters, The Devil’s Vice contained a checklist of gothic elements. The opening shots of Susan, as a woman-in-peril, falling through the space from the top of the stairs onto the hard floor beneath emphasises the importance of the house. This is where much of the film’s events take place (the only other settings are a hospital, a local library, a coffee shop and a police station), with its two staircases also playing prominent roles. Other aspects of the house are significant: there is a mirror on the stairs, several locked doors, focus on a keyhole, creepy portraits (specifically an old black and white formal photograph of a group of children and their schoolteacher, nicknamed ‘Smiler’ by Susan and Richard and seen as a demon), bats in the attic (and later in reference to this a comparison to Dracula’s house) and a disturbing doll in the no-longer needed nursery. In addition to Susan’s status as woman-in-peril she, like many other gothic heroines, is an active investigator who is seeking an answer to what is happening – and engages in the often-present action of walking down the stairs in her nightwear. In keeping with the contemporary setting, Susan is clad in pyjamas rather than a nightdress, and lacks a candlestick to light her way.

Like last session’s The Diary of Sophronia Winters, The Devil’s Vice contained a checklist of gothic elements. The opening shots of Susan, as a woman-in-peril, falling through the space from the top of the stairs onto the hard floor beneath emphasises the importance of the house. This is where much of the film’s events take place (the only other settings are a hospital, a local library, a coffee shop and a police station), with its two staircases also playing prominent roles. Other aspects of the house are significant: there is a mirror on the stairs, several locked doors, focus on a keyhole, creepy portraits (specifically an old black and white formal photograph of a group of children and their schoolteacher, nicknamed ‘Smiler’ by Susan and Richard and seen as a demon), bats in the attic (and later in reference to this a comparison to Dracula’s house) and a disturbing doll in the no-longer needed nursery. In addition to Susan’s status as woman-in-peril she, like many other gothic heroines, is an active investigator who is seeking an answer to what is happening – and engages in the often-present action of walking down the stairs in her nightwear. In keeping with the contemporary setting, Susan is clad in pyjamas rather than a nightdress, and lacks a candlestick to light her way.

More specific references to gothic and horror films abound. The spiral staircase invokes memory of Robert Siodmak’s 1945 film. Susan’s research into the possible presence of a poltergeist summons up thoughts of Tobe Hooper’s Poltergeist (1982), and her misleading suggestion that they call in a catholic priest brought to mind William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973). Other points of plot similarity to gothic films include the pain of child loss (in J.A. Bayona’s The Orphanage, 2007) and concern for Susan expressed by her husband Richard to his wife’s friend (Douglas Sirk’s Sleep My Love, 1948). Aspects of The Devil’s Vice’s style also appeared to be referencing other films: the black and white footage of Richard’s attack on Susan was likened to scenes in Oren Peli’s Paranormal Activity (2009).

expressed by her husband Richard to his wife’s friend (Douglas Sirk’s Sleep My Love, 1948). Aspects of The Devil’s Vice’s style also appeared to be referencing other films: the black and white footage of Richard’s attack on Susan was likened to scenes in Oren Peli’s Paranormal Activity (2009).

Smaller moments also inspired comparisons. The appearance of the sunglass and strange oculist equipment-wearing medium, Madam Barbara, reminded us of Insidious (James Wan, 2010). Shots of Susan painfully and slowly crawling across the floor after being attacked in the kitchen were similar to Michelle Pfeiffer’s attempts to escape her husband in Robert Zemecki’s What Lies Beneath (2000). Richard’s sing-song taunting while addressing Susan by her name as she’s attempting to find proof of his attacks  echoed that in The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980). The colour red also gains significance when Richard is about to repaint the no longer needed nursery in a blood red hue; when combined with The Devil’s Vice’s concern with children and the occult, this made us think of Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968).

echoed that in The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980). The colour red also gains significance when Richard is about to repaint the no longer needed nursery in a blood red hue; when combined with The Devil’s Vice’s concern with children and the occult, this made us think of Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968).

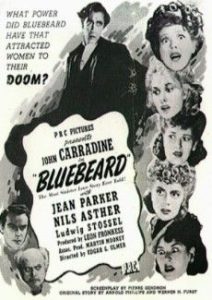

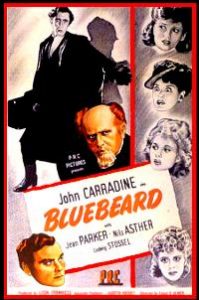

We also brought in our own knowledge of other gothic texts and films. Particular attention was paid to Susan’s moment of realisation that her husband is her attacker. This occurs in the office as she watches footage form the cameras she has placed in the kitchen. It was noted that this pivot is in some ways is akin to Bluebeard’s eight wife entering the secret room which contains the bodies of his previous wives. Such a device was also used in Fritz Lang’s Secret Beyond the Door (1947) when Celia (Joan Bennett) uncovers her husband’s secret.

We also brought in our own knowledge of other gothic texts and films. Particular attention was paid to Susan’s moment of realisation that her husband is her attacker. This occurs in the office as she watches footage form the cameras she has placed in the kitchen. It was noted that this pivot is in some ways is akin to Bluebeard’s eight wife entering the secret room which contains the bodies of his previous wives. Such a device was also used in Fritz Lang’s Secret Beyond the Door (1947) when Celia (Joan Bennett) uncovers her husband’s secret.

The film’s self-aware drawing on of other gothic texts is probably most obvious in its use of Gaslighting. The term comes from Patrick Hamilton’s 1938 play Gaslight (notably filmed in the UK by Thorold Dickinson in 1940 and the US by George Cukor in 1944) in which a husband attempts to make his wife think she is going mad and thus gain control of her fortune. In The Devil’s Vice, Richard engages in such behaviour by placing the creepy photograph in their home. Susan later doubts herself when she remembers that the schoolteacher’s eyes in the photographs have always been closed while Richard insists the opposite is the case. (He has presumably used digital alteration to support his position, since the audience agrees with Susan.) Not all Richard’s manipulations are as clear-cut. His suggestion that Susan research the history of the house seems less than helpful, while his subtle undermining of Susan to her friend Helen and the hospital doctor includes him planting the idea that Susan harms herself. We even wondered if the anti-depressants in Susan’s system were only present because Richard was drugging her in order to undermine her at this point.

The film’s self-aware drawing on of other gothic texts is probably most obvious in its use of Gaslighting. The term comes from Patrick Hamilton’s 1938 play Gaslight (notably filmed in the UK by Thorold Dickinson in 1940 and the US by George Cukor in 1944) in which a husband attempts to make his wife think she is going mad and thus gain control of her fortune. In The Devil’s Vice, Richard engages in such behaviour by placing the creepy photograph in their home. Susan later doubts herself when she remembers that the schoolteacher’s eyes in the photographs have always been closed while Richard insists the opposite is the case. (He has presumably used digital alteration to support his position, since the audience agrees with Susan.) Not all Richard’s manipulations are as clear-cut. His suggestion that Susan research the history of the house seems less than helpful, while his subtle undermining of Susan to her friend Helen and the hospital doctor includes him planting the idea that Susan harms herself. We even wondered if the anti-depressants in Susan’s system were only present because Richard was drugging her in order to undermine her at this point.

Much of this is only seen in retrospect, once it is revealed that Richard is an abuser. This is also true of the way in which Madam Barbara’s ambiguous warning to Susan that ‘he’ will kill her, and that she should leave the house, becomes reframed as a clear denouncement of Richard. Similarly, Susan’s friend Helen asking Susan if she has received the messages she gave to Richard, and indeed her straight forward question of whether Richard is hurting Susan, are afforded extra significance. The oddness of the latter was made more apparent when we considered it later – Helen would hardly have asked this unless she was already concerned. Some of us suspected Richard early on; he seemed too perfect and his ever-ready smile caused us to make connections with ‘Smiler’ in the photograph. In addition, we are familiar with Gothic tropes, and in the gothic the husband is often the perpetrator. Yet like Susan, who is clearly also aware of some of the horror tropes present (she researches the Occult, knows about poltergeists and considers calling in a catholic priest for an exorcism) others in the group, despite their awareness of the related matter of the gothic, only realised later. It was knowledge of horror films which led to this. It occurred just after Richard claimed he had been attacked by the demon – while the woman often sees the demon in horror films, this is far less true of the man.

Much of this is only seen in retrospect, once it is revealed that Richard is an abuser. This is also true of the way in which Madam Barbara’s ambiguous warning to Susan that ‘he’ will kill her, and that she should leave the house, becomes reframed as a clear denouncement of Richard. Similarly, Susan’s friend Helen asking Susan if she has received the messages she gave to Richard, and indeed her straight forward question of whether Richard is hurting Susan, are afforded extra significance. The oddness of the latter was made more apparent when we considered it later – Helen would hardly have asked this unless she was already concerned. Some of us suspected Richard early on; he seemed too perfect and his ever-ready smile caused us to make connections with ‘Smiler’ in the photograph. In addition, we are familiar with Gothic tropes, and in the gothic the husband is often the perpetrator. Yet like Susan, who is clearly also aware of some of the horror tropes present (she researches the Occult, knows about poltergeists and considers calling in a catholic priest for an exorcism) others in the group, despite their awareness of the related matter of the gothic, only realised later. It was knowledge of horror films which led to this. It occurred just after Richard claimed he had been attacked by the demon – while the woman often sees the demon in horror films, this is far less true of the man.

The delayed realisation reveals the success of the film’s attempt to align us with Susan. We spend most of our time with Susan, with Richard’s life away from the house little commented on – we just see him in his pinstripe shirt and suit, setting off for an undemanding day at work. Our alignment is not just in terms of sympathy, but in point of view. This is not strictly literal, but significantly we, like Susan do not physically see her attacker until the camera footage is screened. This means the revelation is indeed a plot twist for some of the audience.

We further pondered Susan and Richard’s relationship, speculating on how long they had been together and when the abuse started. Susan seems highly conditioned to her situation, accepting Richard’s control and her isolation without question. Oddly many of us also accepted Susan’s isolation until considering it more after the screening. In addition to the earlier mention that Richard has isolated Susan from Helen, we found it troubling that she had no friends or family to turn to – even by telephone. The house, in which Susan spends the majority of her time, is also physically isolated – with Richard using the couple’s one car to go to work every day. Some of us even credited Richard with more control than he possessed by wondering if he planted the card for Madam Barbara in the library book on the Occult. What happened during her visit discounted this theory, since Madam Barbara does not reinforce Richard’s ideas on the presence of demons. While Richard has not arranged the Madam Barbara’s appearance, she nonetheless seems frightened of him too since she leaves after giving only an ambiguous warning to Susan, and does not return to check on Susan.

Instead, Susan takes the matter into her own hands. She escalates the situation with Richard by goading the ‘demon’ until he attacks her – in full view of the cameras in the kitchen. Susan is prompted to take this action after ‘Smiler’ has apparently attacked Richard. The couple sits in the car, with Susan at the wheel, ready to drive them both away from the danger in the house. She is stopped by Richard, who asserts that Susan will never be able to escape from the demon, who he claims is feeding off the guilt she feels at losing her unborn children. This argument is illogical since Susan’s miscarriage occurred when she was attacked (seemingly by the demon). Susan does not question Richard’s logic. It is only after Susan sees the visual evidence from the cameras that the two parts of her brain which have previously been dissociated, join together, and she sees Richard as her abuser.

Instead, Susan takes the matter into her own hands. She escalates the situation with Richard by goading the ‘demon’ until he attacks her – in full view of the cameras in the kitchen. Susan is prompted to take this action after ‘Smiler’ has apparently attacked Richard. The couple sits in the car, with Susan at the wheel, ready to drive them both away from the danger in the house. She is stopped by Richard, who asserts that Susan will never be able to escape from the demon, who he claims is feeding off the guilt she feels at losing her unborn children. This argument is illogical since Susan’s miscarriage occurred when she was attacked (seemingly by the demon). Susan does not question Richard’s logic. It is only after Susan sees the visual evidence from the cameras that the two parts of her brain which have previously been dissociated, join together, and she sees Richard as her abuser.

The consequences of this realisation are grim for Susan. Richard hits her over the head with the laptop on which she has been viewing the camera footage. We wondered if perhaps a similar realisation had prompted the attack at the start of the film. It is also possible that Richard deliberately timed it so that causing the loss of her babies would further punish Susan, make her more vulnerable, and place her more fully in his control. Sadly it is the case that an abuser never needs a reason to abuse. The morning after Susan’s discovery, Richard seems a little wary of her. Susan is especially forceful in her squashing of sausages in the frying pan, perhaps causing him, like us, to wonder if he was about to be attacked with this most domestic of weapons. He is right to be concerned. Although Richard foolishly takes at face value Susan’s suggestion they consult a catholic priest, she finally finds proof of his abuse (courtesy of the camera she placed in the fruit bowl which she has previously overlooked) and leaves him.

Symbolically Susan leaves behind her rather ostentatious engagement/wedding ring. Susan and Richard are obviously comfortably off; they rent or own a large house, have a four wheel drive car, neither is overworked, and Susan can spend several hundred pounds on her investigations without blinking. The ring is another sign of this wealth. It is also indicative of something else though. A member of the group was reminded of the Adrienne Rich poem ‘Aunt Jennifer’s Tigers’. This discusses the ‘massive weight of Uncle’s wedding band’ on Aunt Jennifer’s hand and references imperialism and the oppression of women by men. (You can find the full poem here: http://writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/88v/rich-jennifer-tiger.html) As with The Yellow Wallpaper and The Diary of Sophronia Winters, patriarchy is signalled to be damaging, and women are advised to avoid marriage.

Symbolically Susan leaves behind her rather ostentatious engagement/wedding ring. Susan and Richard are obviously comfortably off; they rent or own a large house, have a four wheel drive car, neither is overworked, and Susan can spend several hundred pounds on her investigations without blinking. The ring is another sign of this wealth. It is also indicative of something else though. A member of the group was reminded of the Adrienne Rich poem ‘Aunt Jennifer’s Tigers’. This discusses the ‘massive weight of Uncle’s wedding band’ on Aunt Jennifer’s hand and references imperialism and the oppression of women by men. (You can find the full poem here: http://writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/88v/rich-jennifer-tiger.html) As with The Yellow Wallpaper and The Diary of Sophronia Winters, patriarchy is signalled to be damaging, and women are advised to avoid marriage.

Susan, with the help of technology, manages to extricate herself from her situation. Seeing film footage of Richard attacking her is what makes Susan see the truth, and also provides proof for the police. Susan was also able to access this technology via other technology – she orders the cameras over the internet she perhaps surprisingly has some access to. Technology is not wholly positive, however, since Richard uses it to physically attack Susan.

Such instances of technology clearly place the film in the modern day. The modern is also reflected in the decoration of the central aspect of the house. While it has Gothic elements (an almost church-like appearance, especially evident in its windows) the interior is stylish and modern. The fact it is largely functional also suggests emptiness. There seem to be few personal items, with the main photograph that of a group of children and their schoolteacher. While some Gothic films are set in contemporary times  (notably Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940), Secret Beyond the Door, and Bryan Forbes’ The Stepford Wives (1975)), more often they take place in the past (Gaslight, The Spiral Staircase, Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s Dragonwyck (1946) and Jack Clayton’s The Innocents (1961).

(notably Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940), Secret Beyond the Door, and Bryan Forbes’ The Stepford Wives (1975)), more often they take place in the past (Gaslight, The Spiral Staircase, Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s Dragonwyck (1946) and Jack Clayton’s The Innocents (1961).

Setting films in the past provides the audience with distance from the narrative, to allow them to deny the relevance of the gothic (and its disturbing overtones) to the present day. By contrast, The Devil’s Vice is set in contemporary times since social documentary and feature film maker Peter Watkins-Hughes’ main remit was to raise awareness of domestic abuse and to encourage people to seek help. It was released at the time Clare’s Law –the Domestic Violence Disclosure Scheme was rolled out across the UK. The law allows people with concerns to make enquiries about a partner. You can find out more on the film’s website: http://www.thedevilsvice.org.uk/

We thought that the film was very effective in using its small cast of fewer than ten, limited running time and few locations. These all added to the sense of constraint. However, the tone was occasionally uneven (especially in Helen’s visit to the house seemingly being played for a little comedy), and we found Susan’s desire to return to home a bit unbelievable. Regardless of how much Susan is being controlled, she has suffered not just terrible physical trauma but the emotional effect of losing her unborn babies. This is dealt with quickly. While the focus on extreme physical violence is understandable in terms of seeing what is already in plain sight, it underplays the significance of the more subtle ways people abuse others. Since the film’s release, the matter of coercive control has also been more discussed, and indeed in March 2015 was included in the Serious Crime Act https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/482528/Controlling_or_coercive_behaviour_-_statutory_guidance.pdf)

But the film did raise our awareness in making the connection between Gothic heroines and domestic abuse – whether physical, emotional, or both. This crystallised for us the continuing relevance of the Gothic, especially in a world that continues to be unequal.

As ever, do log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.

We particularly commented on the impactful nature of the first two scenes. In the first, Eddie’s tangle with an impresario comments on Black Swan (2010, Darren Aronofsky) with her success in winning the dual role in Swan Lake prompting Norma to celebrate and reminisce about her own related experience. This second scene also involves an impresario, though Norma is far more knowing, and pushy, than the heroine she references: that of the young female ballet dancer Vicky (Moira Shearer) in The Red Shoes (1948, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressberger). The fact that the both the obsessive female dancer and the figure of the impresario are archetypes – as demonstrated by the act The Red Shoes is based on Hans Christian Andersen’s disturbing fairy tale (1845) – aids the audience’s recognition of both figures even if they are unfamiliar with the films. But the play delves far deeper than this as Norma and Eddie’s relationship to these related but diverging film texts, and of course to each other, are multi-layered.

We particularly commented on the impactful nature of the first two scenes. In the first, Eddie’s tangle with an impresario comments on Black Swan (2010, Darren Aronofsky) with her success in winning the dual role in Swan Lake prompting Norma to celebrate and reminisce about her own related experience. This second scene also involves an impresario, though Norma is far more knowing, and pushy, than the heroine she references: that of the young female ballet dancer Vicky (Moira Shearer) in The Red Shoes (1948, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressberger). The fact that the both the obsessive female dancer and the figure of the impresario are archetypes – as demonstrated by the act The Red Shoes is based on Hans Christian Andersen’s disturbing fairy tale (1845) – aids the audience’s recognition of both figures even if they are unfamiliar with the films. But the play delves far deeper than this as Norma and Eddie’s relationship to these related but diverging film texts, and of course to each other, are multi-layered. While both The Red Shoes and Black Swan focus on a woman’s love/hate relationship with dancing and the control it exerts on her, these women and the contexts of the films are very different. In The Red Shoes the ballerina literally cannot escape her compulsion, dancing up until almost her last moment when she jumps in front of a moving train. In Andersen’s story this a punishment for the pleasure she takes in her beautiful new red slippers she insists on wearing to church, with her only stopping once her slipper-encased feet have gruesomely been chopped off. The more modern Black Swan couches Nina Sayers’ (Natalie Portman) breakdown as the pressure between the oppositional good and bad characters she plays on stage, with the moral judgment of women seen in Andersen’s fairy tale replaced by recognition of the pressures women are under.

While both The Red Shoes and Black Swan focus on a woman’s love/hate relationship with dancing and the control it exerts on her, these women and the contexts of the films are very different. In The Red Shoes the ballerina literally cannot escape her compulsion, dancing up until almost her last moment when she jumps in front of a moving train. In Andersen’s story this a punishment for the pleasure she takes in her beautiful new red slippers she insists on wearing to church, with her only stopping once her slipper-encased feet have gruesomely been chopped off. The more modern Black Swan couches Nina Sayers’ (Natalie Portman) breakdown as the pressure between the oppositional good and bad characters she plays on stage, with the moral judgment of women seen in Andersen’s fairy tale replaced by recognition of the pressures women are under. While Norma changes little, Eddie develops, after a crisis of identity leads to a period of estrangement and meaning that Eddie following her own path. Here the recognisable film tropes of women empowering themselves through education (Erin Brockovich, 2000, Steven Soderbergh) and of films’ makeover scenes (Clueless, 1995, Amy Heckerling) shine a light on the way audiences in general respond to stars, including as an ego ideal inspiring self-development. Norma is also ‘made-over’ (references to the classic Now Voyager, 1942, Irving Rapper) but her empowerment comes through her manipulation of men (The Damned Don’t Cry, 1950, Vincent Sherman). Even for modern day theatre audiences who might not be familiar with these specific (though widely available and mostly Hollywood) film texts, the fact they reference themes disseminated in films and indeed these themselves reflect their presence in other art forms/discourses of entertainment widens their appeal, reach and relevance. The script sets up the matter of how specific (though imaginary) audience members might appropriate material from well-known films with female stars whose characters undergo some sort of transformation. Furthermore, as film academics, many of us historians, this bridges the gap between historical audiences who can seem difficult to grasp, offering some insights into how texts are read, re-read and re-purposed including as part of people’ life narratives.

While Norma changes little, Eddie develops, after a crisis of identity leads to a period of estrangement and meaning that Eddie following her own path. Here the recognisable film tropes of women empowering themselves through education (Erin Brockovich, 2000, Steven Soderbergh) and of films’ makeover scenes (Clueless, 1995, Amy Heckerling) shine a light on the way audiences in general respond to stars, including as an ego ideal inspiring self-development. Norma is also ‘made-over’ (references to the classic Now Voyager, 1942, Irving Rapper) but her empowerment comes through her manipulation of men (The Damned Don’t Cry, 1950, Vincent Sherman). Even for modern day theatre audiences who might not be familiar with these specific (though widely available and mostly Hollywood) film texts, the fact they reference themes disseminated in films and indeed these themselves reflect their presence in other art forms/discourses of entertainment widens their appeal, reach and relevance. The script sets up the matter of how specific (though imaginary) audience members might appropriate material from well-known films with female stars whose characters undergo some sort of transformation. Furthermore, as film academics, many of us historians, this bridges the gap between historical audiences who can seem difficult to grasp, offering some insights into how texts are read, re-read and re-purposed including as part of people’ life narratives. A particularly enjoyable and fruitful discussion revolved around the matter of pre-code films. This too relates to the matter of historically situated audiences as many today would be unaware that some films before the implementation of this heavier censorship in Hollywood (the Production or Hays Code in 1934) actually referenced matters like prostitution, child abuse and other weighty issues. We specifically discussed the pre-code Baby Face (1933, Alfred E. Green) – a film credited as partly responsible for more censorship being necessary. In this, Lily (Barbara Stanwyck) is a young woman who after years of abuse, including being prostituted by her own father, is encouraged (ironically enough by a man) to use men the way men have always used her – to employ sex for her own ends. Although Lily is in some ways ‘normalised’ – although she cold-heartedly climbs the ladder of executives at the company she is employed by she eventually marries her boss and realising her love for him she later sacrifices her hard-won jewellery – she still gains through using her sexual powers, although she may of course be given special justification due to the awful abuse she has suffered.

A particularly enjoyable and fruitful discussion revolved around the matter of pre-code films. This too relates to the matter of historically situated audiences as many today would be unaware that some films before the implementation of this heavier censorship in Hollywood (the Production or Hays Code in 1934) actually referenced matters like prostitution, child abuse and other weighty issues. We specifically discussed the pre-code Baby Face (1933, Alfred E. Green) – a film credited as partly responsible for more censorship being necessary. In this, Lily (Barbara Stanwyck) is a young woman who after years of abuse, including being prostituted by her own father, is encouraged (ironically enough by a man) to use men the way men have always used her – to employ sex for her own ends. Although Lily is in some ways ‘normalised’ – although she cold-heartedly climbs the ladder of executives at the company she is employed by she eventually marries her boss and realising her love for him she later sacrifices her hard-won jewellery – she still gains through using her sexual powers, although she may of course be given special justification due to the awful abuse she has suffered. We contrasted this to The Damned Don’t Cry which is referenced in the play as Norma regales Eddie, and us, with how she used men to further her own financial standing. The Damned Don’t Cry is a somewhat uneven film, veering from severe sympathy for Edith Whitehead/Lorna Hansen Forbes (Joan Crawford) after the loss of her child and perhaps some delight in her turning the tables on men, though she does not have such a damaged background as Lily in Baby Face. Furthermore in the post-code and more conservative early 1950s Ethel/Lorna is punished by the killing of the man she loves by the one she has betrayed.

We contrasted this to The Damned Don’t Cry which is referenced in the play as Norma regales Eddie, and us, with how she used men to further her own financial standing. The Damned Don’t Cry is a somewhat uneven film, veering from severe sympathy for Edith Whitehead/Lorna Hansen Forbes (Joan Crawford) after the loss of her child and perhaps some delight in her turning the tables on men, though she does not have such a damaged background as Lily in Baby Face. Furthermore in the post-code and more conservative early 1950s Ethel/Lorna is punished by the killing of the man she loves by the one she has betrayed.