Watching these two very different films gave us much food for thought. In addition to tracing elements of the Gothic and Bluebeard fable across two texts, it afforded the opportunity to compare silent and sound films, as well as French and Hollywood productions.

Barbe Bleue’s treatment of the Bluebeard fable was fairly in keeping with Charles Perrault’s 1697 version of the traditional folktale. At only 9 minutes long, we were surprised that some of the scenes were so lengthy. In particular, the long wedding banquet scene added little to the tension of the woman in peril. Neither did it match some of the comedy scenes in the film – notably the proposed wife’s clear disdain for Bluebeard in the opening scene, or the ‘below stairs’ hijinks of the servants.

The scenes where the latest wife was encouraged by the devil to enter the forbidden room and submitted to this temptation were more successfully realised. Both gave Melies an opportunity to show off his special effects. The discovery of the previous wives’ hanging bodies was suitably striking.

We were surprised by the fact this was undercut in the next few scenes as, after a short period of panic and struggle with her husband, the rescue occurred quickly and all Bluebeard’s wives were brought back to life. While this last action fitted Melies’ reputation for screening the fantastical, it affects the film’s impact, especially as all the women are given a final scene happy ending in which they marry noblemen.

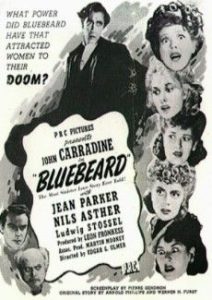

Despite this non-traditional ending to the story, Ulmer’s film was even less true the traditional Bluebeard tale than Melies’. The film focuses on puppet-maker and painter Gaston Morrell – a serial killer of women in Paris. In a warning poster the killer is referred to as a ‘Bluebeard’. But Morrell is not married to these women, which made us ponder the use of the term – especially as the film’s title. It certainly draws on the horror so important to the Bluebeard tale, however, potentially signalling that this was important to audiences of the time.

Ulmer’s film contained more horror than Melies’ – as befits the director of spine-chilling The Black Cat (1934) starring horror stalwarts Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff. There was little suspense in terms of the killer though. After initial scenes of melodramatic moral panic, and the lengthy puppet opera, the confirmation of the identity of ‘Bluebeard’ was fairly swift. This was first implied by Gaston Morrell’s (John Carradine) emergence from the fog to make acquaintance with the heroine of the story – Lucille (Jean Parker). As well as echoing similar scenes in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lodger (1927), the detail of the framing was significant: the meeting occurred in front of the warning poster. Not long after, Morrell’s murder of his lover, Renee (Sonia Sorel), takes place on screen.

little suspense in terms of the killer though. After initial scenes of melodramatic moral panic, and the lengthy puppet opera, the confirmation of the identity of ‘Bluebeard’ was fairly swift. This was first implied by Gaston Morrell’s (John Carradine) emergence from the fog to make acquaintance with the heroine of the story – Lucille (Jean Parker). As well as echoing similar scenes in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lodger (1927), the detail of the framing was significant: the meeting occurred in front of the warning poster. Not long after, Morrell’s murder of his lover, Renee (Sonia Sorel), takes place on screen.

Ulmer was especially known for his talent for mise en scene – indeed American film critic Andrew Sarris assessed that this was the one notable aspect of his work (Andrew Sarris, The American Cinema, New York, Dutton, 1968, p. 143). We were struck by  some of the backgrounds of Morrell’s paintings. We were also impressed by Ulmer’s use of chiaroscuro to emphasise the gothic spaces of Morrell’s apartment as well as the scenes in the sewers below. Despite the latter being somewhat derivative of Gaston Leroux’s The Phantom of the Opera (1909), elsewhere another echo – this time of Melies’ film when the most recent wife discovered the previous ones– proved especially effective as dangling shadowy puppets eerily appear on the walls of Morrell’s apartment. It is also notable that the film uses Killer point-of-view as

some of the backgrounds of Morrell’s paintings. We were also impressed by Ulmer’s use of chiaroscuro to emphasise the gothic spaces of Morrell’s apartment as well as the scenes in the sewers below. Despite the latter being somewhat derivative of Gaston Leroux’s The Phantom of the Opera (1909), elsewhere another echo – this time of Melies’ film when the most recent wife discovered the previous ones– proved especially effective as dangling shadowy puppets eerily appear on the walls of Morrell’s apartment. It is also notable that the film uses Killer point-of-view as  shots of Morrell’s eyes spying through a hole prior to the puppet show as he searches for Lucille. We’ve previously discussed Killer POV in relation to The Spiral Staircase (1945, Robert Siodmak: see https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2015/12/02/summary-of-discussion-on-the-spiral-staircase/), and it is interesting that Ulmer’s use occurred first and that he had previously worked with Siodmak.

shots of Morrell’s eyes spying through a hole prior to the puppet show as he searches for Lucille. We’ve previously discussed Killer POV in relation to The Spiral Staircase (1945, Robert Siodmak: see https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2015/12/02/summary-of-discussion-on-the-spiral-staircase/), and it is interesting that Ulmer’s use occurred first and that he had previously worked with Siodmak.

Our definition of the Gothic involving the Woman in Peril had obviously played an important part in Melies’ film though, as mentioned earlier, this was relatively short-lived in the silent. Here the tension is ratcheted up, as Lucille continually places herself in danger. Firstly, she declares herself not to be scared of Bluebeard, then she visits Morrell alone in his apartment, later confronting him here, again alone, even once she suspects the truth.

There is another Woman in Peril – Lucille’s sister Francine (Teala Loring) – who appears part-way through the film. It is suggested that she is an undercover agent,  working with the police, though this is not made clear. She too places herself in danger (presumably often a part of her job), by luring Morrell into a trap – both are women who actively investigate. When Francine appeared it almost seemed she had usurped Lucille, but with former’s death at hands of Morrell, Lucille was once more the heroine. While both women investigate, only Francine – who is actually employed as a detective (especially surprising in the 19th century) is punished by death though.

working with the police, though this is not made clear. She too places herself in danger (presumably often a part of her job), by luring Morrell into a trap – both are women who actively investigate. When Francine appeared it almost seemed she had usurped Lucille, but with former’s death at hands of Morrell, Lucille was once more the heroine. While both women investigate, only Francine – who is actually employed as a detective (especially surprising in the 19th century) is punished by death though.

We noted that the film was rather odd tonally. This includes its shaky grasp of its historical and geographic setting – not all that unusual in Hollywood productions. While the costumes (women’s dresses with bustles) broadly suggest the 19th century, the amount of ankle on show was deemed inaccurate. Although set in Paris, the only European accent was contributed by Swedish actor Nils Asther as Police Inspector Lefevre.

The uneven tone is especially notable in the film’s mix of comedy and horror. When in court trying to ascertain the painter of a particular picture, the questioning of artists’ models – one of whom replies in a thick Brooklyn accent – leads to responses of hilarity  by those attending. Much of this revolved around suggestions of prostitution – references also found elsewhere in the film, including as Morrell’s justification of his crimes. In addition, the killing scenes, whether an eye-bulging arms-raised action or a protracted and ineffective fight, were a bit comical. We noted these comedy elements in a horror film contrasted to Carry on Screaming’s (1966, Gerald Thomas) mostly comic, but occasionally, frightening tone.

by those attending. Much of this revolved around suggestions of prostitution – references also found elsewhere in the film, including as Morrell’s justification of his crimes. In addition, the killing scenes, whether an eye-bulging arms-raised action or a protracted and ineffective fight, were a bit comical. We noted these comedy elements in a horror film contrasted to Carry on Screaming’s (1966, Gerald Thomas) mostly comic, but occasionally, frightening tone.

The pacing of the film was also patchy. We especially wondered why so much time was spent on the enacting of the puppet opera near the film’s beginning. This does, however, give the film audience time to ponder the significance of the fact that Morrell is playing (and singing) the part of Faust in the production, while an older man plays the film’s hero. This disjuncture further helps suggest the fact Morrell is the serial killer at large. Non-diegetic music was also effectively used to punctuate melodramatic moments.

The extended musical scenes also caused us to further compare Ulmer’s sound and Melies’ silent films. In both, the killer got his comeuppance, with Morrell in the later film throwing himself into the Seine. Happy endings are also suggested in both. This occurs more forcefully in the earlier production when all the previously dead wives come back to life and are married off. In Ulmer’s film the relationship between Lucille and the Police Inspector appears to grow.

You can find an English translation of Perrault’s tale here: http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/perrault03.html

Both films are viewable on archive.org:

https://archive.org/details/Barbe-bleue

https://archive.org/details/Bluebeard

Do log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.