Exciting gothic news! Frances Kamm and Tamar Jeffers McDonald have released the Call For Papers for the University of Kent’s third Gothic Feminism conference. ‘Technology, Women and Gothic-Horror On-Screen’ will take place from the 2nd to the 3rd of May.

The call for papers:

Technology, Women, and Gothic-Horror On-Screen

2 – 3 May 2019

University of Kent

Keynote speaker: Dr Lisa Purse (University of Reading)

CALL FOR PAPERS

Gothic and technology appear, on the surface, to evoke contradictory connotations. As David Punter and Glennis Byron highlight, the Gothic came to be a term associated with the “ornate and convoluted”, “excess and exaggeration, the product of the wild and the uncivilized, a world that constantly tended to overflow cultural boundaries” (Punter and Byron, 2004, 7). Technology, on the other hand, is a term often linked to science, innovation and progressive invention. If the Industrial Revolution is emblematic of what one imagines a technological revolution to be, then technology becomes synonymous with the associations defining 18th Century culture, described by Terry Castle as “the period as an age of reason and enlightenment – the aggressively rationalist imperatives of the epoch” (Castle, 1995, 8).

Yet technology and the Gothic have been linked and have interacted since the latter’s beginnings in fiction. From the earliest reception of the original novels that give our Gothic films their name, fans and critics alike referred to the “machinery” of the narratives, implying that that the mechanisms that made them go were audible. Clara Reeve, who wrote The Old English Baron – itself is a tad creaky – commented on The Castle of Otranto that “the machinery is so violent, that it destroys the effect it is intended to excite” (Reeve, 2008, 3). And Horace Walpole, himself, made reference to the story’s “engine” (Walpole, 2014, 6). The Gothic can thus be conceptualised as metaphorically mechanical, a link explored within a different context by Jack Halberstam who writes that “Gothic fiction is a technology of subjectivity … designed to produce fear and desire within the reader” (Halberstam, 1995, 2).

Technology and the Gothic have also intersected in more literal terms, as with the horror created by the intersection of the two in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). On the one hand, the novel stands as a canonical Gothic text, and Ellen Moers argues that the story can be defined as the Female Gothic, a term commonly associated with the women-in-peril narratives which later saw the influence of Gothic literature translated onto the cinema screen in Hollywood during the 1940s. On the other hand, the tale of an unnatural and scientific birth is credited with establishing the generic tropes of science fiction, a mode of storytelling which is indebted to technology and acknowledges “contemporary scientific knowledge and the scientific method”, as Barry Keith Grant suggests. He also continues: “Science fiction, quite unlike fantasy and horror, works to entertain alternative possibilities” (Grant, 2004, 17). However, Fred Botting notes that the combining of science fiction and Gothic – two “generic monsters” – reveals a “a long and interwoven association” whereby both genres “give form to a sense of otherness, a strangeness that is difficult to locate” (Botting, 2008, 131).

Our conference aims to explore this relationship between technology and the Gothic by focussing upon its intersection as depicted on screen within visual media, with a specific focus on how such concerns impact on gender representations and, in particular, women. This connection may be explored figuratively: the “machinery” identified in Gothic fiction can also be extended to the filmic Gothics which centre upon the Gothic heroine. The Hollywood 1940s Gothics possess noticeably excessive convolutions of plot, as with Sleep, My Love (1948), and one could argue this trend has continued in contemporary returns to the Old Dark House and horror with films like Crimson Peak (2015). Technology may also be physically present within these Gothic-horror films. If the “machinery is so violent” in Crimson Peak’s narrative, then this is additionally foregrounded within the diegesis: Thomas Sharpe’s engine for extracting the red clay from the ground stands as both a metaphor for the genre’s mechanical plot – drawing on familiar tropes which unearth deadly secrets – as well as functioning as a visual spectacle around which the climax of the film shall take place.

Actual mechanical or technological inventions which impact upon the story may be wide-ranging: the railway, cars, telephones, recording devices, electric light and gaslight are just some examples of technologies integrated into the narratives of Gothic films, often with the intention of contributing to the imperilment and oppression of the central heroine. Technology can also do this by evoking the uncanny, itself a phenomenon which forms “the background and indeed the modus operandi of much Gothic fiction” (Punter and Byron, 2004, 286). Tom Gunning demonstrates this when he recounts several versions in early cinema of a woman-in-jeopardy story, Heard Over the Phone, which could almost be Gothic in that the woman is in her own home and menaced there by a male assailant. Drawing on Freud’s musings upon the ambivalent nature of technology, Gunning highlights the ambiguous – and uncanny – position of the telephone: it is a device which brings the absent near through sound, but actually this serves only to underline the actual distances involved. Gothic-type narratives, gender, and technology merge in these early films to reveal “the darker aspects of the dream world of instant communication and the annihilation of space and time” (Gunning, 1991, 188).

More recent Gothic and Gothic-horror films may update these technologies to include computers, the Internet and mobile phones. Technology also includes film and the moving image itself: this conference will explore how filmic technologies mediate and emphasise the connection between technology, the Gothic, and gender, including through the use of visual effects. Film is a particularly apt medium through which to contemplate these ideas as cinema’s ontology embodies both technology’s scientific roots and the Gothic’s appeal to excess and the supernatural. As Murray Leeder notes: “With its ability to record and replay reality and its presentation of images that resemble the world but as intangible half-presences, cinema has been described as a haunted or ghostly medium from early on” (Leeder, 2015, 3).

These ideas may also be explored by expanding upon the original notion of Moer’s Female Gothic: if the literary Female Gothic is defined by female writers working in this mode, then this conference would also like to explore how female filmmakers have made use of Gothic-horror conventions. It is significant to note that the most iconic examples of Gothic films focusing on stories about the victimisation of women, particularly in the 1940s, were directed by men. By thinking about the technology behind the screen, this event will also consider what influence women filmmakers have had upon this tradition, including within present day, and what further reflections may be offered between this relationship of the Gothic to gender and technology.

With this third annual Gothic Feminism conference, we invite scholars to respond to the theme of technology in the woman-in-jeopardy strand of the Gothic and Gothic-horror film or television.

Topics can include but are not limited to:

– the tension between Gothic and technology as the supernatural, fantastic and paranoia versus the rational, reason and logic. How do these elements intersect with the representation of gender in film and television?

– the traditions of the Gothic heroine on-screen and her interaction with technology. Does technology help the female character or is it another agent of terror used against her?

– the technology behind the screen. How have female filmmakers used the genres of Gothic-horror to express themselves?

– the technology of the screen. How has the technology of cinema, including visual effects, been used, and how do these aspects interact with the representation of the central female protagonist/s?

Please submit proposals of 500 words, along with a short biographical note (250 words) to gothicfeminism2016@gmail.com by Friday 15th February 2019.

We welcome 20-minute conference papers as well as submissions for creative work or practice-as-research including, but not limited to, short films and video essays.

Conference organisers: Frances A. Kamm and Tamar Jeffers McDonald

https://twitter.com/GothicFeminism

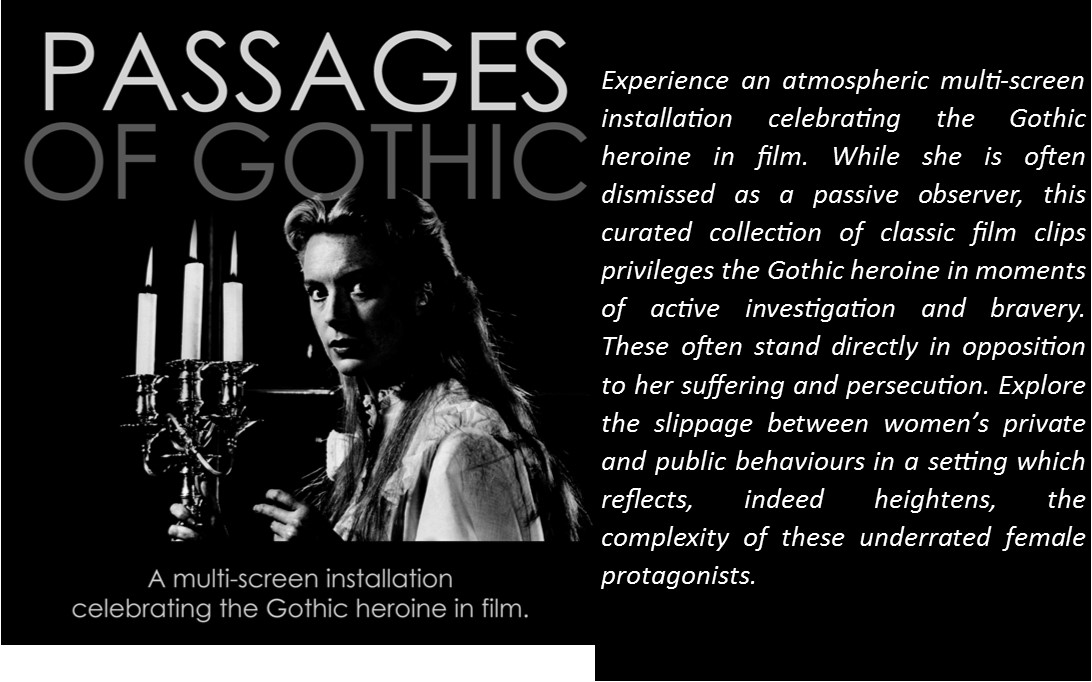

This conference is the third annual event from the Gothic Feminism project, working with the Melodrama Research Group in the Centre of Film and Media Research at the University of Kent. Gothic Feminism explores the representation of the Gothic heroine on-screen in her various incarnations.

References

Botting, Fred. (2008). Gothic Romanced: Consumption, Gender and Technology in Contemporary Fictions. London and New York: Routledge.

Castle, Terry. (1995). The Female Thermometer: 18th Century Culture and the Invention of the Uncanny. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gunning, Tom. (1991). “Heard Over the Phone: The Lonely Villa and the de Lorde Tradition of the Terrors of Technology.” In: Screen. 32:2. 184-196.

Grant, Barry Keith. (2004). “‘Sensuous Elaboration’: Reason and the Visible in the Science Fiction Film.” In: Redmond, Sean. (ed). Liquid Metal: The Science Fiction Film Reader. New York, Chichester: Wallflower Press.

Halberstam, Jack. (1995). Skin Shows: Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Leeder, Murray. (ed). (2015). Cinematic Ghosts: Haunting and Spectrality From Silent Cinema to the Digital Era. New York and London: Bloomsbury.

Punter, David and Glennis Byron. (2004). The Gothic. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Reeve, Clara. (2008). The Old English Baron. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Walpole, Horace. (2014). The Castle of Otranto. Oxford: Oxford University Press.