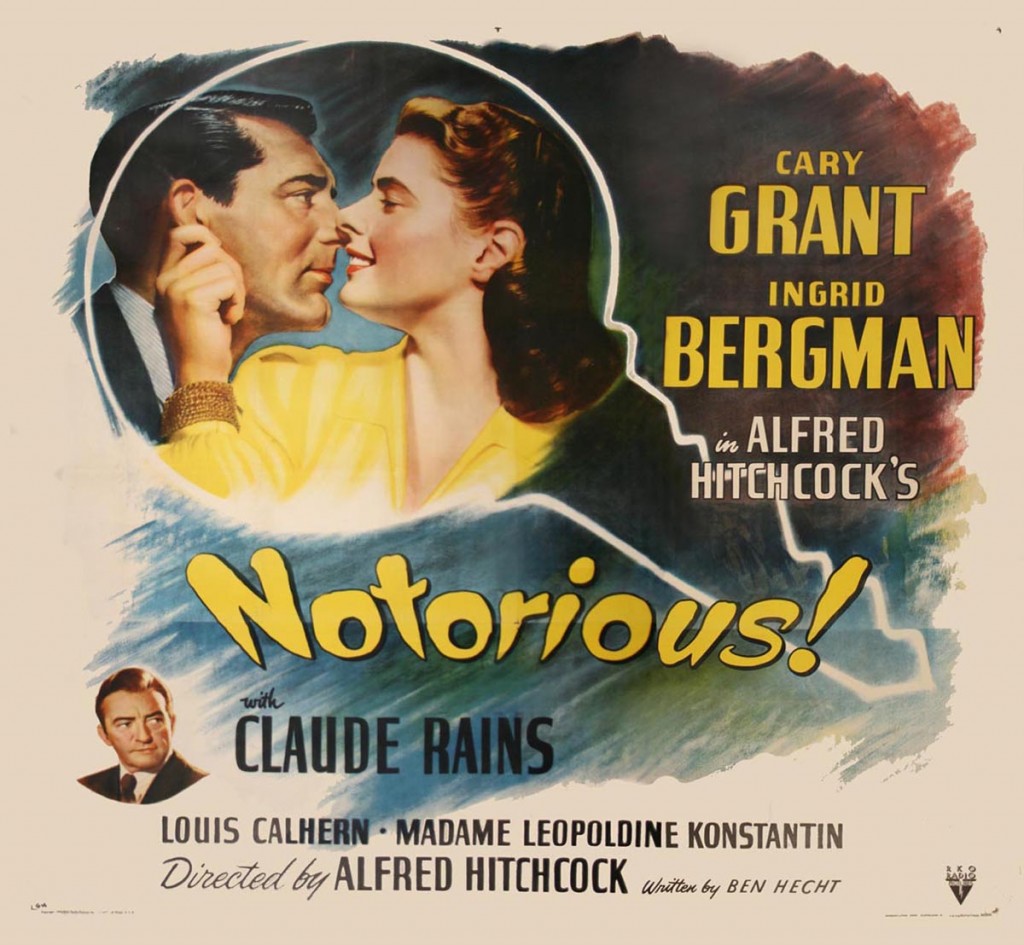

Our discussion on Notorious ranged across various aspects relating to melodrama and the gothic, also touching on production and reception issues and the recent film Crimson Peak.

An initial comment related to the film’s music. This was expressive throughout – including at moments when emphasis has already been provided visually. Several quick camera zooms into characters’ faces, poisoned cups of coffee, and vitally important keys were also punctuated by music. We thought it was interesting that the most suspenseful scene of the film was not heavily scored. The final scene in which Devlin (Cary Grant) has finally come to Alicia’s (Ingrid Bergman’s) rescue and has to face down her Nazi husband Alexis (Claude Rains) and his mother (Madame Konstantin) uses the characters’ looks to convey the tension.

important keys were also punctuated by music. We thought it was interesting that the most suspenseful scene of the film was not heavily scored. The final scene in which Devlin (Cary Grant) has finally come to Alicia’s (Ingrid Bergman’s) rescue and has to face down her Nazi husband Alexis (Claude Rains) and his mother (Madame Konstantin) uses the characters’ looks to convey the tension.

The film’s opening is also intriguing. In this, Alicia is seen flirting with an unknown and silent man who only appears from behind, sat in a chair. This is especially sinister since Alicia seems to be so open with her smiles. While this functions to build up to Grant’s star entrance, it also foreshadows the danger he (as Devlin) encourages her to place herself in. As an American Intelligence agent he is involved in recruiting her and remains her contact throughout. He even enables the Alicia and her target –Alexis – to be reacquainted by placing her in physical danger. He gives her horse a surreptitious kick to necessitate the nearby Alexis to ride to her rescue.

The film’s opening is also intriguing. In this, Alicia is seen flirting with an unknown and silent man who only appears from behind, sat in a chair. This is especially sinister since Alicia seems to be so open with her smiles. While this functions to build up to Grant’s star entrance, it also foreshadows the danger he (as Devlin) encourages her to place herself in. As an American Intelligence agent he is involved in recruiting her and remains her contact throughout. He even enables the Alicia and her target –Alexis – to be reacquainted by placing her in physical danger. He gives her horse a surreptitious kick to necessitate the nearby Alexis to ride to her rescue.

The woman-in-peril aspect is complicated however by the fact Alicia willingly places herself in extreme danger from the very start. This is especially seen in her drink-driving which conveys that following her father’s imprisonment for treason she does not care if she lives or dies. This places Devlin in danger for one of the few times in the film. Alicia faces far more danger and heartache – marrying a man she knows to be a Nazi when she is in love with Devlin.

herself in extreme danger from the very start. This is especially seen in her drink-driving which conveys that following her father’s imprisonment for treason she does not care if she lives or dies. This places Devlin in danger for one of the few times in the film. Alicia faces far more danger and heartache – marrying a man she knows to be a Nazi when she is in love with Devlin.

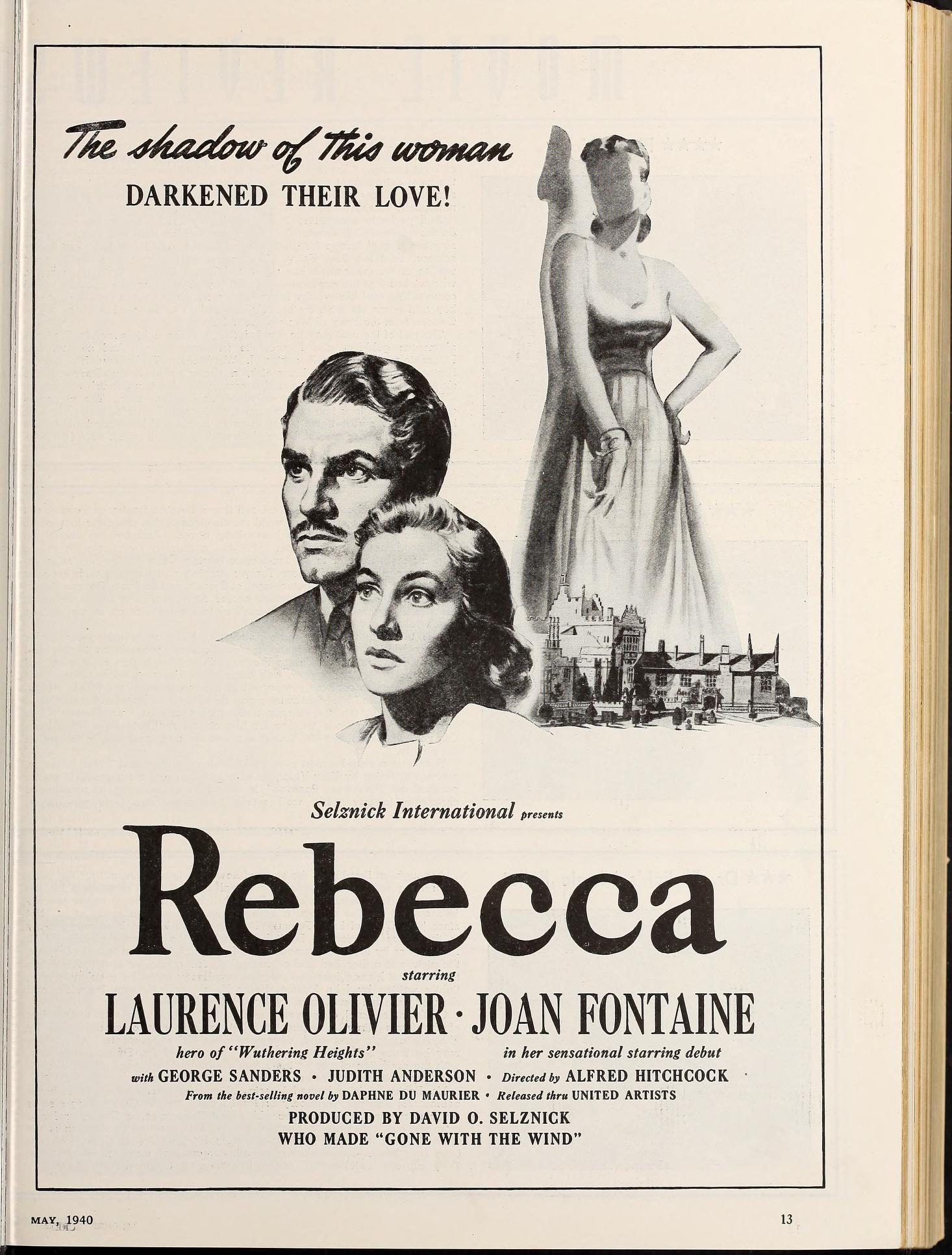

Such a tense marriage can be related to other gothic heroines in films we have recently screened. In In Gaslight (1944) (another film in which Bergman starred) her character’s husband meant her harm. We can contrast this to Rebecca (1940) in which the heroine also marries for love, and rightly grows suspicious of her husband, Maxim. This is proved to be unfounded in relation to the second Mrs de Winter’s own safety, however.

Such a tense marriage can be related to other gothic heroines in films we have recently screened. In In Gaslight (1944) (another film in which Bergman starred) her character’s husband meant her harm. We can contrast this to Rebecca (1940) in which the heroine also marries for love, and rightly grows suspicious of her husband, Maxim. This is proved to be unfounded in relation to the second Mrs de Winter’s own safety, however.

There are also useful comparisons in terms of Rebecca’s heroine as an ‘almost investigator’. Alicia is far more active than the second Mrs de Winter, fulfilling the role of spy. She also differs to the second Mrs de Winter (and several other gothic heroines) in her drunkenness. The fairly blatant communication of her apparent sexual promiscuity contrasts even more sharply to chaste, innocent heroines. By Alicia’s own admission to Devlin that she is a ‘crook’ as well as a ‘tramp’.

investigator’. Alicia is far more active than the second Mrs de Winter, fulfilling the role of spy. She also differs to the second Mrs de Winter (and several other gothic heroines) in her drunkenness. The fairly blatant communication of her apparent sexual promiscuity contrasts even more sharply to chaste, innocent heroines. By Alicia’s own admission to Devlin that she is a ‘crook’ as well as a ‘tramp’.

The fact Alicia appears in modern fashionable clothes contrasts to several other gothic heroines. Many of the other films we have screened are set in earlier periods (the late 1800s Gaslight, the early 20th century in The Spiral Staircase (1945)). Even the contemporary second Mrs de Winter only becomes comfortable in fashionable clothes as the film progresses. Alicia’s riding gear which is not only formal but includes a mannish tie contrasts to the second Mrs de Winter’s soft femininity.

The fact Alicia appears in modern fashionable clothes contrasts to several other gothic heroines. Many of the other films we have screened are set in earlier periods (the late 1800s Gaslight, the early 20th century in The Spiral Staircase (1945)). Even the contemporary second Mrs de Winter only becomes comfortable in fashionable clothes as the film progresses. Alicia’s riding gear which is not only formal but includes a mannish tie contrasts to the second Mrs de Winter’s soft femininity.

A more specific aspect of setting often associated with the gothic, the mansion house, is also present in Notorious. Alicia moves to Alexis’ house following their marriage and scenes of the lavish party they throw convey a sense of space. It is significant that Alicia is not allowed access to all areas of her new home. Notably the key to the wine cellar, highlighted in the previous post’s advertisement for the film, is kept by Alexis. The wine cellar’s role as dangerous space also compares to The Spiral Staircase. A staircase also plays an important part in Notorious. It conveys Alexis’ mother’s sense of ownership as she sweeps down them to meet Alicia for the first time and is the setting for the film’s climax. Devlin’s tense rescue of Alicia involves him carrying her down the staircase.

the gothic, the mansion house, is also present in Notorious. Alicia moves to Alexis’ house following their marriage and scenes of the lavish party they throw convey a sense of space. It is significant that Alicia is not allowed access to all areas of her new home. Notably the key to the wine cellar, highlighted in the previous post’s advertisement for the film, is kept by Alexis. The wine cellar’s role as dangerous space also compares to The Spiral Staircase. A staircase also plays an important part in Notorious. It conveys Alexis’ mother’s sense of ownership as she sweeps down them to meet Alicia for the first time and is the setting for the film’s climax. Devlin’s tense rescue of Alicia involves him carrying her down the staircase.

The smaller trope of the candle-carrying which we have noticed in other gothic films was also noticeable – though given a twist. Instead of carrying a candle or torch to aid with her investigations, Alicia holds a fan throughout the hosting of the party. This signals the deceit she is practicing on her husband and also nods to the film’s romantic moments – the film’s beginning brings to mind a romantic comedy. Significantly candles are most obviously present as a mood-setter for Alicia and Devlin’s outdoor picnic before their romance turns sour and she marries Alexis. The fact Devlin remains Alicia’s contact throughout the film also comments on the film’s romantic, rather than realistic, point of view as it allows for their relationship to play out.

The smaller trope of the candle-carrying which we have noticed in other gothic films was also noticeable – though given a twist. Instead of carrying a candle or torch to aid with her investigations, Alicia holds a fan throughout the hosting of the party. This signals the deceit she is practicing on her husband and also nods to the film’s romantic moments – the film’s beginning brings to mind a romantic comedy. Significantly candles are most obviously present as a mood-setter for Alicia and Devlin’s outdoor picnic before their romance turns sour and she marries Alexis. The fact Devlin remains Alicia’s contact throughout the film also comments on the film’s romantic, rather than realistic, point of view as it allows for their relationship to play out.

We also discussed some of the film’s other characters.  We found Alexis’ mother especially compelling. Dorothy Kilgallen’s November 1946 Modern Screen piece on the film (cited in the previous post) compared Madame Konstantin’s performance to that of Judith Anderson, as Mrs Danvers, in Rebecca (p. 138). We also spoke a little about Madame Konstantin’s earlier stage career and roles in European films. This was her main Hollywood role and like other emigres who had fled the Nazis, it is ironic that she played a Nazi in Notorious.

We found Alexis’ mother especially compelling. Dorothy Kilgallen’s November 1946 Modern Screen piece on the film (cited in the previous post) compared Madame Konstantin’s performance to that of Judith Anderson, as Mrs Danvers, in Rebecca (p. 138). We also spoke a little about Madame Konstantin’s earlier stage career and roles in European films. This was her main Hollywood role and like other emigres who had fled the Nazis, it is ironic that she played a Nazi in Notorious.

It was also mentioned that several aspects of the film relate to a recent release which drew on the gothic. In Crimson Peak (2015), like Notorious, the heroine is poisoned by a drink and carried out of the house at the film’s end. This reveals the continued relevance of melodramatic and gothic tropes.

Consideration of Crimson Peak also flagged up Notorious’ very different production and reception contexts. While the later film is very sexually explicit, sexual references made in Notorious were rather explicit for their time – especially given the censorship of Hollywood films operating. In addition to general comments about Alicia’s sexual behaviour, it is heavily hinted that she has pre-marital sex with Alexis. The lengthy kiss between Devlin and Alicia was censored, however, with constant distractions and discussion about dinner technically meaning it did not last long enough to be considered objectionable. We also noted that alcohol was very freely enjoyed by Alicia – a contrast to a decade earlier when films such as The Thin Man (1934) were criticised for such scenes.

Consideration of Crimson Peak also flagged up Notorious’ very different production and reception contexts. While the later film is very sexually explicit, sexual references made in Notorious were rather explicit for their time – especially given the censorship of Hollywood films operating. In addition to general comments about Alicia’s sexual behaviour, it is heavily hinted that she has pre-marital sex with Alexis. The lengthy kiss between Devlin and Alicia was censored, however, with constant distractions and discussion about dinner technically meaning it did not last long enough to be considered objectionable. We also noted that alcohol was very freely enjoyed by Alicia – a contrast to a decade earlier when films such as The Thin Man (1934) were criticised for such scenes.

It was said that the key which played such an important role in the film also had an interesting afterlife. Apparently Grant took it from the set and sent it to Bergman when she was in disgrace for her adulterous affair with the Italian director Roberto Rossellini. Later still, Bergman returned it to Hitchcock.

We also spoke about Bergman’s star image. She was half-German as well as half-Swedish but unsurprisingly the latter was far more foregrounded in information circulated about her in 1930s and 1940s Hollywood. Bergman’s international heritage was also utilised in her screen image as she often played characters who were not native to the countries in which her films were made. These extended to not just the United States, but Germany and Italy.

As ever, do log in to comment or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.