Posted by Sarah

All are welcome to attend the fourth of this term’s screening and discussion sessions which will take place on the 19th of February in Keynes Seminar Room 6, from 4pm to 7pm.

We will be screening The Awakening (2011, Nick Murphy, 107 mins).

Frances has very kindly provided the following introduction:

Following on from Kat’s screening of Black Christmas last week, this week’s film The Awakening is another example of the intersection between horror and melodrama in the

Gothic tradition. The Awakening picks up many of the Gothic tropes present in Black Christmas, such as the woman-in-peril and dark house motifs, but uses these elements for a very different effect.

The Awakening  is a 2011 British horror film starring Rebecca Hall, Dominic West and Imelda Staunton and directed by Nick Murphy. In many ways the film contributes to the popularity of the haunted house and ghost story narratives which have been featured and revived in many recent horror films, such as the Paranormal Activity series (2009-present) and, in particular, The Woman in Black (2012 and another British horror film). The Awakening also shares many similarities with The Orphanage (2007), as it seeks to combine a classic chilling story of a house haunted by a supernatural presence with the aftermath of traumatic historic events: in The Awakening’s case, Britain in 1921 after World War One. The Awakening tells the story of writer Florence Cathcart who has made her name as a paranormal sceptic and now helps the police in exposing and arresting charlatans who host spiritualism meetings and séances which promise to reunite paying customers with family members and the soldiers who did not return from the war. A war veteran and teacher, Robert Mallory, meets Florence and requests she return with him to his boarding school in the countryside, where he believes a real ghost of a former schoolboy is haunting the premises. Although initially reluctant at first, Florence agrees to return with Robert and prove the ghost a fraud, and thereby restore order to the school and the boys who believe the recent death of their school friend to be caused by a malicious spirit. With the help of her scientific equipment, Florence quickly believes the mystery to be solved and the ‘ghost’ exposed as a childish prank, until further paranormal occurrences begin to take place and Florence is forced to question her beliefs…

is a 2011 British horror film starring Rebecca Hall, Dominic West and Imelda Staunton and directed by Nick Murphy. In many ways the film contributes to the popularity of the haunted house and ghost story narratives which have been featured and revived in many recent horror films, such as the Paranormal Activity series (2009-present) and, in particular, The Woman in Black (2012 and another British horror film). The Awakening also shares many similarities with The Orphanage (2007), as it seeks to combine a classic chilling story of a house haunted by a supernatural presence with the aftermath of traumatic historic events: in The Awakening’s case, Britain in 1921 after World War One. The Awakening tells the story of writer Florence Cathcart who has made her name as a paranormal sceptic and now helps the police in exposing and arresting charlatans who host spiritualism meetings and séances which promise to reunite paying customers with family members and the soldiers who did not return from the war. A war veteran and teacher, Robert Mallory, meets Florence and requests she return with him to his boarding school in the countryside, where he believes a real ghost of a former schoolboy is haunting the premises. Although initially reluctant at first, Florence agrees to return with Robert and prove the ghost a fraud, and thereby restore order to the school and the boys who believe the recent death of their school friend to be caused by a malicious spirit. With the help of her scientific equipment, Florence quickly believes the mystery to be solved and the ‘ghost’ exposed as a childish prank, until further paranormal occurrences begin to take place and Florence is forced to question her beliefs…

The film incorporates many of the major themes and tropes of the Gothic, as established by the Gothic literature of the 18th century and the Bluebeard tale, which in turn inspired the Gothic cycle of films in Hollywood in the 1940s beginning with Rebecca (1940). Florence is the Gothic heroine of the film who is compelled to investigate the mystery of an old, dark house: in this case, the boarding school. In unlocking the secrets of the house, Florence becomes the woman-in-jeopardy conventionally at the heart of these stories: Florence is imperilled by the supernatural presence in the house; by the threats posed by the shady groundskeeper Edward Judd; and by her own stubbornness to question her rationalist convictions. In keeping with the traditions of the Gothic, the film’s narrative hinges on the revelation of a hidden secret which comes to light through Florence’s investigation. In The Awakening this secret is not contained within a single secret, locked room (as conventionally seen in such Bluebeard-inspired tales) but rather the house itself is the mystery to Florence, which must be discovered and understood in order to reveal the building’s – and her own – troubled past. As such we explore the house and experience the supernatural sightings with Florence and this identification with the female protagonist shows the film’s correlation to the conventions of horror established by films like Black Christmas, as discussed last week. The film adheres to other horror generic conventions, particularly in respect to low key lighting and the threat conveyed through effective editing and camera movement, but The Awakening is not just concerned with shocks and jumps. In his 2011 review of the film, Guardian critic Peter Bradshaw describes the film as a ‘supernatural melodrama’ and this description becomes very apt. The film’s horror elements work to illuminate and

The film incorporates many of the major themes and tropes of the Gothic, as established by the Gothic literature of the 18th century and the Bluebeard tale, which in turn inspired the Gothic cycle of films in Hollywood in the 1940s beginning with Rebecca (1940). Florence is the Gothic heroine of the film who is compelled to investigate the mystery of an old, dark house: in this case, the boarding school. In unlocking the secrets of the house, Florence becomes the woman-in-jeopardy conventionally at the heart of these stories: Florence is imperilled by the supernatural presence in the house; by the threats posed by the shady groundskeeper Edward Judd; and by her own stubbornness to question her rationalist convictions. In keeping with the traditions of the Gothic, the film’s narrative hinges on the revelation of a hidden secret which comes to light through Florence’s investigation. In The Awakening this secret is not contained within a single secret, locked room (as conventionally seen in such Bluebeard-inspired tales) but rather the house itself is the mystery to Florence, which must be discovered and understood in order to reveal the building’s – and her own – troubled past. As such we explore the house and experience the supernatural sightings with Florence and this identification with the female protagonist shows the film’s correlation to the conventions of horror established by films like Black Christmas, as discussed last week. The film adheres to other horror generic conventions, particularly in respect to low key lighting and the threat conveyed through effective editing and camera movement, but The Awakening is not just concerned with shocks and jumps. In his 2011 review of the film, Guardian critic Peter Bradshaw describes the film as a ‘supernatural melodrama’ and this description becomes very apt. The film’s horror elements work to illuminate and frame the personal (and often private) melodramas which affect each character. The teachers of the school fail to conceal these tragedies as these secrets are also revealed within the course of Florence’s investigation. Central topics include shell-shock, child abuse and death.

frame the personal (and often private) melodramas which affect each character. The teachers of the school fail to conceal these tragedies as these secrets are also revealed within the course of Florence’s investigation. Central topics include shell-shock, child abuse and death.

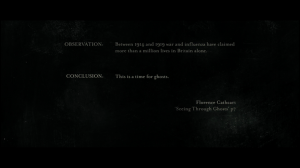

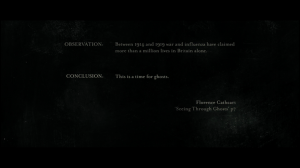

The film extends the Gothic trope of the house revealing secrets to include Florence herself, as The Awakening ultimately performs an in-depth analysis of the heroine and her psyche as well. This commingling of the paranormal or the mysterious with scientific and rational reasoning is a  reoccurring trend in the narrative and becomes key to unlocking the secret of Florence and her past. This is evident from the film’s very first frames, when we see a quotation from Florence’s popular book about the debunking of spirits informing us of the high death rate in Britain recently and concluding: ‘This is a time for ghosts’. This sentiment is supported by the opening scene which sees Florence attend a séance. Yet this first ghostly encounter is quickly revealed to be a fraud by Florence, who has the proponents of the meeting arrested. Florence maintains her sceptical, rationalist ideals through the use of advanced technological devices to prove the boarding school’s sightings of ghosts to be a hoax, only to have this same scientific equipment ‘prove’ the opposite is true. The narrative’s vacillation between incredulity and belief highlights the importance of the film’s setting in post-war Britain. The years following the First World War – a conflict which would radically re-define modern warfare and the devastating impact of technology – saw an increase in the popularity of spiritualism and belief in the paranormal. It is important to note that Freud’s essay on the uncanny was also published at this time, in 1919. The uncanny has a long history, which is interwoven with the Gothic tradition and literature of the 18th century, but the fact that Freud should choose to publish his work on the uncanny at this time is significant. Just as the world was recovering from the shock and trauma of the ‘modern’ – in this case, modern warfare – Freud muses upon the affect a displacement from the world, like an experience of the uncanny, has upon the mind. Like Florence, Freud hopes to offer a scientific explanation for these occurrences although, by his own admission, he ultimately fails. It is therefore important to view the film in terms of the uncanny as well, because the concept helps contextualise the historical setting for the film and The Awakening effectively incorporates many of the motifs which Freud identifies as ripe for an uncanny experience. These include representations of the double; the slippage between what is known to be alive or dead; and the unheimlich or the unhomely nature of the house. In testament to Freud’s work, The Awakening reveals that the secret behind the melodrama, the cause of the horror and ‘the uncanny is that species of the frightening that goes back to what was once well known and has long been familiar.’

reoccurring trend in the narrative and becomes key to unlocking the secret of Florence and her past. This is evident from the film’s very first frames, when we see a quotation from Florence’s popular book about the debunking of spirits informing us of the high death rate in Britain recently and concluding: ‘This is a time for ghosts’. This sentiment is supported by the opening scene which sees Florence attend a séance. Yet this first ghostly encounter is quickly revealed to be a fraud by Florence, who has the proponents of the meeting arrested. Florence maintains her sceptical, rationalist ideals through the use of advanced technological devices to prove the boarding school’s sightings of ghosts to be a hoax, only to have this same scientific equipment ‘prove’ the opposite is true. The narrative’s vacillation between incredulity and belief highlights the importance of the film’s setting in post-war Britain. The years following the First World War – a conflict which would radically re-define modern warfare and the devastating impact of technology – saw an increase in the popularity of spiritualism and belief in the paranormal. It is important to note that Freud’s essay on the uncanny was also published at this time, in 1919. The uncanny has a long history, which is interwoven with the Gothic tradition and literature of the 18th century, but the fact that Freud should choose to publish his work on the uncanny at this time is significant. Just as the world was recovering from the shock and trauma of the ‘modern’ – in this case, modern warfare – Freud muses upon the affect a displacement from the world, like an experience of the uncanny, has upon the mind. Like Florence, Freud hopes to offer a scientific explanation for these occurrences although, by his own admission, he ultimately fails. It is therefore important to view the film in terms of the uncanny as well, because the concept helps contextualise the historical setting for the film and The Awakening effectively incorporates many of the motifs which Freud identifies as ripe for an uncanny experience. These include representations of the double; the slippage between what is known to be alive or dead; and the unheimlich or the unhomely nature of the house. In testament to Freud’s work, The Awakening reveals that the secret behind the melodrama, the cause of the horror and ‘the uncanny is that species of the frightening that goes back to what was once well known and has long been familiar.’

When watching the film we can think about:

– How The Awakening fits into this Gothic tradition

– Why the film has this historical setting

– Florence’s characterisation

– The ending: what does it all mean?

Do join us if you can for this chilling screening!