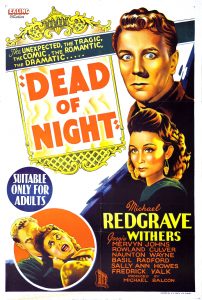

Dead of Night proved to be suitably spooky pre-Christmas fare, and prompted much discussion on its unusual structure, its gothic and uncanny elements, as well as its lasting influence.

It is first worth noting that the version of the film we watched was that which was originally released in the UK (102 mins, October 1945), and not the edited US edition (77 mins, released June 1946). Both included at least some of the wraparound narrative of the architect Walter Craig (Mervyn Johns) visit to Eliot Foley’s (Ronald Culver) house, its consequences, and the restarting of the tale. There were significant cuts in the US however. According to contemporaneous sources, the US version excluded the second (The Christmas Party) and the fourth (The Golfing Story) sequences, keeping the first (The Hearse), the third (The Haunted Mirror) and the fifth (The Ventriloquist’s Dummy) (New Movies: the National Board of Review Magazine, August –September 1946, pp. 6-7).

It is first worth noting that the version of the film we watched was that which was originally released in the UK (102 mins, October 1945), and not the edited US edition (77 mins, released June 1946). Both included at least some of the wraparound narrative of the architect Walter Craig (Mervyn Johns) visit to Eliot Foley’s (Ronald Culver) house, its consequences, and the restarting of the tale. There were significant cuts in the US however. According to contemporaneous sources, the US version excluded the second (The Christmas Party) and the fourth (The Golfing Story) sequences, keeping the first (The Hearse), the third (The Haunted Mirror) and the fifth (The Ventriloquist’s Dummy) (New Movies: the National Board of Review Magazine, August –September 1946, pp. 6-7).

We particularly commented on the Englishness of the two tales cut from the US release. In the Christmas Party sequence the large house was occupied by upper class characters, with cut-glass accents, enjoying games of sardines and blind man’s bluff. This was reminiscent of Charles Dickens’ narrative of Scrooge’s previously happy  Christmases in A Christmas Carol (1843). Meanwhile, the golfing buddies are played by Basil Radford (George) and Naunton Wayne (Larry). The comic duo were especially familiar to UK audiences, not just as Charters and Caldicott in The Lady Vanishes (1938, Alfred Hitchcock) but other films whose release was more limited to the UK – including Crook’s Tour (1941, John Baxter) and Millions Like Us (1943, Sidney Gilliat and Frank Launder).

Christmases in A Christmas Carol (1843). Meanwhile, the golfing buddies are played by Basil Radford (George) and Naunton Wayne (Larry). The comic duo were especially familiar to UK audiences, not just as Charters and Caldicott in The Lady Vanishes (1938, Alfred Hitchcock) but other films whose release was more limited to the UK – including Crook’s Tour (1941, John Baxter) and Millions Like Us (1943, Sidney Gilliat and Frank Launder).

As well as the specific Englishness of these sequences perhaps making them unsuitable for US audiences, the decision may have also be related to the time of year of the releases: the Christmas Party sequence seems more appropriate to Autumn than Summer. We found the horror anthology nature of the film reminiscent of M.R. James whose tales of ghosts have become a Christmas staple. Notably it was not just the Christmas ghost tale removed from the US release, but also the only other tale with ghosts.

We turned to more detailed discussion of the sections, noting that each of these contained an uncanny element. In the first, The Hearse sequence, it was commented on that the immobility of the doctor’s (Robert Wyndham) left arm, while well disguised, became a point of focus for some.

The Cavalcanti-directed Christmas Party sequence was especially gothic. The shadowy shots of the large space, especially the stairs, are effective. This combined with the appearance to Sally (Sally Ann Howes) of a suitably creepy ghost child summoned up gothic associations. This child names himself as Francis Kent. Other characters assert that his older sister Constance was his killer. This refers to the real-life case of 1860 in which a sixteen year old had murdered her four year old brother. It gained much publicity five years later, and again in 2008 with the publication of Kate Summerscale’s The Suspicions of Mr Whicher. The bringing in of such a notorious case serves to blur the boundary between fiction and reality, adding to the sense of unease.

that his older sister Constance was his killer. This refers to the real-life case of 1860 in which a sixteen year old had murdered her four year old brother. It gained much publicity five years later, and again in 2008 with the publication of Kate Summerscale’s The Suspicions of Mr Whicher. The bringing in of such a notorious case serves to blur the boundary between fiction and reality, adding to the sense of unease.

The woman-in-peril aspect of the gothic was especially seen in the third narrative – the Haunted Mirror. In this, the teller of the tale, Joan (Googie Withers) is in great danger from her new husband Peter (Ralph Michael). He has seemingly been possessed by the spirit of a bed-bound, violent and jealous husband of a century before. This is caused by Joan’s present of an antique mirror in which the husband sees a different background reflected. Joan is only saved when she literally breaks the mirror whilst being strangled by her husband with a scarf.

The woman-in-peril aspect of the gothic was especially seen in the third narrative – the Haunted Mirror. In this, the teller of the tale, Joan (Googie Withers) is in great danger from her new husband Peter (Ralph Michael). He has seemingly been possessed by the spirit of a bed-bound, violent and jealous husband of a century before. This is caused by Joan’s present of an antique mirror in which the husband sees a different background reflected. Joan is only saved when she literally breaks the mirror whilst being strangled by her husband with a scarf.

While the previous Christmas Party sequence seems firmly anchored in the past by its referencing of the Kent case and its Dickensian overtones, the Haunted Mirror had a more modern feel to it. While it too looked back at the past, we found it more striking in terms of the comment it makes on post-war masculinity. Peter seems passive – especially in his lack of interest in getting married, and searching for a house, while Joan drives things forward. She sets off the entire narrative by purchasing the mirror. Joan’s active nature is also seen as she is pictured sitting on Peter’s double bed, in his presence, before they are married. The last action of the sequence – Joan’s mirror-breaking during her husband’s only attempt to take charge – comments further on this. Another odd aspect we commented on was the other main character of the sequence- the antiques shop owner (Esme Percy). His strange manner, especially his lengthy clutching of Joan’s hands when she returns to the store, seems to make the possibility of a supernatural, rather than a psychological, cause even more likely.

Another odd aspect we commented on was the other main character of the sequence- the antiques shop owner (Esme Percy). His strange manner, especially his lengthy clutching of Joan’s hands when she returns to the store, seems to make the possibility of a supernatural, rather than a psychological, cause even more likely.

Our main thoughts about the golfing sequence involved its comic value – perhaps providing a breather for the audience. One of the key moments, when Larry walks into the water and drowns after having lost the round of golf, and therefore the girl, Mary (Peggy Bruce), who figures as the ‘prize’ – is not very funny though. Nor did we find it scary – life in the narrative simply goes on without him. The ambivalence is furthered when it is implied that after the disappearance of the newly married George and the presence, though invisible, of Larry, the latter will simply take the former’s place (maybe a further reason for the fact this section is not seen in the US release).

Our main thoughts about the golfing sequence involved its comic value – perhaps providing a breather for the audience. One of the key moments, when Larry walks into the water and drowns after having lost the round of golf, and therefore the girl, Mary (Peggy Bruce), who figures as the ‘prize’ – is not very funny though. Nor did we find it scary – life in the narrative simply goes on without him. The ambivalence is furthered when it is implied that after the disappearance of the newly married George and the presence, though invisible, of Larry, the latter will simply take the former’s place (maybe a further reason for the fact this section is not seen in the US release).

We found the final sequence (the Ventriloquist’s Dummy) the most disturbing of the individual narratives. There are unsettling moments throughout, including the dummy Hugo seeming to move from one place to another without help. The switching of the ventriloquist Maxwell Frere (Michael Redgrave) and Hugo’s voices at the end of the sequence was particularly striking – visually and aurally.

We found the final sequence (the Ventriloquist’s Dummy) the most disturbing of the individual narratives. There are unsettling moments throughout, including the dummy Hugo seeming to move from one place to another without help. The switching of the ventriloquist Maxwell Frere (Michael Redgrave) and Hugo’s voices at the end of the sequence was particularly striking – visually and aurally.

The ways in which the sequences can be compared, as well as the wraparound narrative, were also discussed. The relation of the tellers to their narratives is interesting. The first 3 play significant parts in the flashback sequences – though notably only the wife and not her passive husband is present at the house to tell of the tale of the Haunted Mirror. Given the proximity of the tellers to these spooky tales, they remain surprisingly unruffled by these earlier experiences – all only proffering their narratives once prompted by Craig.

Noticeably the Golfing story sequence is more tangential to its teller Foley, the owner of the house and gatherer of the guests. It is understandable that neither of the golfing buddies can tell the tale- one has managed to disappear while the other in invisible. In addition to the teller being somewhat disconnected from the story, since he is a bystander, the ambivalence towards death referred to earlier, blurs the boundary between life and death.

The final sequence also involves its teller – the psychiatrist Dr Van Straaten (Frederick Valk)– to a lesser degree. The reason for the lack of Maxwell Frere at the house is more sinister than previous one – he has gone insane. It is also significant that by telling the tale, the doctor is afforded, and indeed lends, an authority to it – and indeed to his assertions throughout that there is an explicable, psychological reason for Craig’s sense of déjà vu. It is presumably that it is just this which inspires Craig to strangle him.

The final sequence also involves its teller – the psychiatrist Dr Van Straaten (Frederick Valk)– to a lesser degree. The reason for the lack of Maxwell Frere at the house is more sinister than previous one – he has gone insane. It is also significant that by telling the tale, the doctor is afforded, and indeed lends, an authority to it – and indeed to his assertions throughout that there is an explicable, psychological reason for Craig’s sense of déjà vu. It is presumably that it is just this which inspires Craig to strangle him.

All the narratives satisfyingly come together at the end. The characters are still present in Foley’s house, but there is splicing of various spaces we know cannot be geographically related – for example the separate spaces of the Christmas Party house and the prison. This adds to the sense of terror. We agreed that the most terrifying moment was when the dummy ‘walks’. The circularity of the narrative was also deemed especially effective as there was not just a wraparound story, but the restarting of the film’s beginning with Walter Craig again visiting Foley’s house, once more with a feeling of déjà vu.

in Foley’s house, but there is splicing of various spaces we know cannot be geographically related – for example the separate spaces of the Christmas Party house and the prison. This adds to the sense of terror. We agreed that the most terrifying moment was when the dummy ‘walks’. The circularity of the narrative was also deemed especially effective as there was not just a wraparound story, but the restarting of the film’s beginning with Walter Craig again visiting Foley’s house, once more with a feeling of déjà vu.

We concluded with comments about the influence of the film. While the production of horror films had been banned in the UK during the war the genre exploded following the film’s release. More specific influence has also been attributed to the scene in which Frere switches his voice to that of his dummy. It is echoed at the end of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). Jez Conolly and David O. Bates comment on this, as well as the reading of the tussle between the two ventriloquists over the male dummy as a love triangle (Dead of Night, Columbia University Press, 2015). More recently, the presence of the character the Ventriloquist in Batman films is perhaps a nod to this horror classic.

As ever, do log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.

I hope you all have a peaceful Christmas and New Year.