by Rory Butcher

This summer I have been consumed by my master’s dissertation. I promised myself I wouldn’t, and truth be told I never expected I would be. In September 2018, I had anticipated researching Waterloo or the Peninsula War – as all good budding Napoleonic historians do. But of course, the first casualty of battle is always the plan. By early this year, I had concluded that I was going to research something far more niche. And so, I discovered the Fencible Regiments.

This summer I have been consumed by my master’s dissertation. I promised myself I wouldn’t, and truth be told I never expected I would be. In September 2018, I had anticipated researching Waterloo or the Peninsula War – as all good budding Napoleonic historians do. But of course, the first casualty of battle is always the plan. By early this year, I had concluded that I was going to research something far more niche. And so, I discovered the Fencible Regiments.

In 1793, with Britain suddenly thrust into a war with Revolutionary France, the British Army was in a spot of bother. They weren’t fully prepared to fight an army which was upwards of 600,000 men – and so rushed to recruit men to defend against a French invasion. One of the ways these men were recruited was to enlist them in these Fencible Regiments. The regular army was considered “too much” by many, and so these were the alternative. They were paid the same as the regulars, disciplined the same as the regulars, and drilled the same as the regulars; but they weren’t to serve overseas without the express permission of every man. Despite the fact that the Fencible Establishment was, at its largest, over 30,000 men (1/6 of the entire British Army payroll), there has been little to no substantial research into their existence. So I found myself investigating a series of regiments with files barely touched at the National Archives, and scouring various journal catalogues for any mention of them.

Now why is this relevant to the rather wonderful view of Edinburgh at the top of this article, I hear you ask? Well, because a large proportion of the Fencibles were Scottish. Of the 55 infantry regiments raised, 44 were Scottish. Of the approximately 30 cavalry regiments, 14 were Scottish. It therefore became rather pertinent to my research that I visit the archives which reside in Edinburgh. So off I went!

It has been 9 years since I was last in the Scottish capital, but I had forgotten how beautiful the city is! When I first arrived, however, I did not have long to dwell. I was straight off to the National Library, just off the Royal Mile. A killer climb to be sure, but at the top of it a very welcome break. As is always sensible at these places, I had gone through their catalogue ahead of time, and requested the documentation I thought would be most useful to this research. Some of the wonderful material I was able to uncover included: a copy of the list of officers in the first Fencible regiments, and even 3 accounts of trials involving men in the regiments! One of these court martials was for eight soldiers, all implicated in a mutinous uprising. It being a library, I was also overjoyed to read through several books which are either out of print, or never went into print. These would not have been accessible down south, and so made the trip worthwhile on their own.

I then spent the next three days of my trip at the Public Records Office of Scotland, in one of the grandest archive buildings I’ve ever been in. The National Archives at Kew are lovely, but are not the most visually stimulating. The PRO has its own private garden! It is also a much smaller affair, and fosters a closer relationship between researchers and the archivists. Some of the material I uncovered there was equally astonishing – several items were from family collections, and so I found myself promising to contact them if I wanted to make use of them in any publication! There I was able to access commission forms, regimental ledgers, and lots of correspondence. I have often struggled to read historic letters, on the basis of the handwriting alone, but they did become a little easier knowing that I was the only person who was going to read them otherwise! I will admit my frustration with the rather perplexing differences in spelling, though – inlist and publick especially.

Two gems I wish to note here are as follows. The first is a series of letters written by one of the Colonels of a Fencible Regiment to the Secretary at War, demanding that he be given permanent rank in the army. Being a Fencible, his rank would otherwise expire at the end of the war, and so a series of 7 letters over nearly 18 months remain of his constant demanding for this confirmation. He specifically complains at one point that another officer ‘got the rank he now holds in purchase alone, and he held no commission in the army a few months ago.’ You can almost feel the frustration.

Two gems I wish to note here are as follows. The first is a series of letters written by one of the Colonels of a Fencible Regiment to the Secretary at War, demanding that he be given permanent rank in the army. Being a Fencible, his rank would otherwise expire at the end of the war, and so a series of 7 letters over nearly 18 months remain of his constant demanding for this confirmation. He specifically complains at one point that another officer ‘got the rank he now holds in purchase alone, and he held no commission in the army a few months ago.’ You can almost feel the frustration.

The other noteworthy items were a shock to me. When men enlisted into any regular regiment, their names, physical descriptions, previous occupations, and place of birth were recorded in an inventively named “Description Book”. The historian Edward Coss researched the British army in 1808, and only found 11 of these for the entire regular infantry. The PRO had 2 Fencible Description Books, buried amongst other paperwork of the regiments. I was astounded enough when I uncovered the first, but the second one truly blew me away. These were some of the rarest documentation in British military history, and I was able to read 2 of them.

As you can imagine, that was probably the highlight of my week. Although, of course, after the archives had closed in the afternoon my wanderings around Edinburgh were very enjoyable. I was able to squeeze in visits to the National Portrait Gallery, and to St Giles’ Cathedral. I even managed to convince myself to enter a purveyor of Scottish whisky – oh the horror(!)

As you can imagine, that was probably the highlight of my week. Although, of course, after the archives had closed in the afternoon my wanderings around Edinburgh were very enjoyable. I was able to squeeze in visits to the National Portrait Gallery, and to St Giles’ Cathedral. I even managed to convince myself to enter a purveyor of Scottish whisky – oh the horror(!)

So this piece has had two outcomes, really. The first is that the obscure archives really do hold treasures; if you, the reader, do want to undertake research into a niche facet of history do be sure to scour all possible avenues for material. And the second is that Edinburgh is a gorgeous place, and I am very lucky to have been able to visit it, and have it prove a useful investment of my time academically, as well as personally!

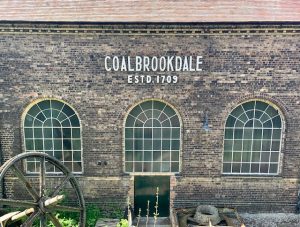

As a first-time visitor to Coalbrookdale, I could’ve been mistaken for Owen Wilson, considering how many times I said, “wow.” I mean, who knew that Ironbridge is so much more than literally just an iron bridge? Imagine my surprise when I learned that the Ironbridge Gorge museum network is actually comprised of ten separate heritage sites, including the Blists Hill Victorian Town, the Coalport China Museum, and the Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron, where I spent the majority of my far-too-short time in Shropshire.

As a first-time visitor to Coalbrookdale, I could’ve been mistaken for Owen Wilson, considering how many times I said, “wow.” I mean, who knew that Ironbridge is so much more than literally just an iron bridge? Imagine my surprise when I learned that the Ironbridge Gorge museum network is actually comprised of ten separate heritage sites, including the Blists Hill Victorian Town, the Coalport China Museum, and the Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron, where I spent the majority of my far-too-short time in Shropshire. Set upon the grounds which served as the birthplace of industry, the Museum of Iron illustrates the lives and work of the family of Abraham Darby. As a staunch Quaker, studying and developing the craft of a skilled tradesman was an obvious path for Abraham Darby. Darby’s notoriety surpassed that of an ordinary artisan, however, when he perfected a method of smelting iron in a blast furnace which was fueled by coke as opposed to charcoal.

Set upon the grounds which served as the birthplace of industry, the Museum of Iron illustrates the lives and work of the family of Abraham Darby. As a staunch Quaker, studying and developing the craft of a skilled tradesman was an obvious path for Abraham Darby. Darby’s notoriety surpassed that of an ordinary artisan, however, when he perfected a method of smelting iron in a blast furnace which was fueled by coke as opposed to charcoal.

Admittedly, I knew very little about Coalbrookdale prior to my visit, but after driving past the Abraham Darby Academy and the Abraham Darby Sports and Leisure Centre, I felt it was safe to assume that the men who bore the name were a pretty big deal. What I did not anticipate, however, was how important women were in securing Abraham Darby’s place in history. In the Quaker faith and in the Darby family business, regardless of any legislative factors, men and women were acknowledged as equal, which offered all individuals access to the same educational and employment opportunities. As this is a history blog rather than a political rant, I shall continue onward, with no further comments or comparisons.

Admittedly, I knew very little about Coalbrookdale prior to my visit, but after driving past the Abraham Darby Academy and the Abraham Darby Sports and Leisure Centre, I felt it was safe to assume that the men who bore the name were a pretty big deal. What I did not anticipate, however, was how important women were in securing Abraham Darby’s place in history. In the Quaker faith and in the Darby family business, regardless of any legislative factors, men and women were acknowledged as equal, which offered all individuals access to the same educational and employment opportunities. As this is a history blog rather than a political rant, I shall continue onward, with no further comments or comparisons.

Grade I Listed status), and touring the Darby family houses, situated atop the hill alongside the workers’ quarters really puts into perspective both the massive scale of the family’s iron-making operation and its commitment to the Ironbridge Gorge community. For less casual history buffs, the Coalbrookdale Research Library and Archive house rich primary resources, including personal diaries, private correspondence, photographic collections, and local ephemera which reinforce the region’s importance in the Industrial Revolution.

Grade I Listed status), and touring the Darby family houses, situated atop the hill alongside the workers’ quarters really puts into perspective both the massive scale of the family’s iron-making operation and its commitment to the Ironbridge Gorge community. For less casual history buffs, the Coalbrookdale Research Library and Archive house rich primary resources, including personal diaries, private correspondence, photographic collections, and local ephemera which reinforce the region’s importance in the Industrial Revolution.

We had visited the museum as part of the project’s military history aspect, and the Royal Green Jackets Museum is one of several museums that ambassadors will be visiting, or indeed have already visited, over the next couple of weeks. The other museums are the Princess of Wales Royal Regiment at Dover Castle, the Royal Welch Fusiliers Museum at Caernarfon Castle, and the Highlanders Museum in Fort George. The aim of the project is to create a pop-up exhibition to be displayed in the museums, highlighting the role the British Army played in this period, with a particular emphasis on the Napoleonic Wars. The exhibition hopes to ‘fill in the blanks’, so to speak, with what the current museums offer with regards to Napoleonic history, exploring the history of recruitment for the British Army among other aspects. As a military history student at the University of Kent, it is sad to see that the school curriculums never seem to truly tackle military history, and so the project hopes to introduce this vital aspect of the Age of Revolutions back into schools.

We had visited the museum as part of the project’s military history aspect, and the Royal Green Jackets Museum is one of several museums that ambassadors will be visiting, or indeed have already visited, over the next couple of weeks. The other museums are the Princess of Wales Royal Regiment at Dover Castle, the Royal Welch Fusiliers Museum at Caernarfon Castle, and the Highlanders Museum in Fort George. The aim of the project is to create a pop-up exhibition to be displayed in the museums, highlighting the role the British Army played in this period, with a particular emphasis on the Napoleonic Wars. The exhibition hopes to ‘fill in the blanks’, so to speak, with what the current museums offer with regards to Napoleonic history, exploring the history of recruitment for the British Army among other aspects. As a military history student at the University of Kent, it is sad to see that the school curriculums never seem to truly tackle military history, and so the project hopes to introduce this vital aspect of the Age of Revolutions back into schools.

The structure of the event was simple. The course was divided up into various sections, based either on period or theme. The students spent thirty minutes on each section which was itself divided into a lecture to revise the basic facts and a discussion period where various sources were analysed. There were also frequent breaks to refresh both mind and body, which stopped the students from losing too much focus. The source section was where Ben and I swung into action, roaming around the room attempting to broaden and improve the students understanding and analytical skills.

The structure of the event was simple. The course was divided up into various sections, based either on period or theme. The students spent thirty minutes on each section which was itself divided into a lecture to revise the basic facts and a discussion period where various sources were analysed. There were also frequent breaks to refresh both mind and body, which stopped the students from losing too much focus. The source section was where Ben and I swung into action, roaming around the room attempting to broaden and improve the students understanding and analytical skills.

Five minutes before the end, the organizers allowed us to give a short talk on the Age of Revolution project which we used to spread the word about the projects aims and achievements. The students seemed interested although this may have been simply relief that their ordeal was almost at an end! With that the day ended, with the students departing for their homes and Ben and I for the tube in a successful attempt to beat the rush hour throng.

Five minutes before the end, the organizers allowed us to give a short talk on the Age of Revolution project which we used to spread the word about the projects aims and achievements. The students seemed interested although this may have been simply relief that their ordeal was almost at an end! With that the day ended, with the students departing for their homes and Ben and I for the tube in a successful attempt to beat the rush hour throng.

Hi! My name is Becky Beach and I have recently been recruited as the Project Administrator to provide administrative support to the Waterloo 200 legacy project.

Hi! My name is Becky Beach and I have recently been recruited as the Project Administrator to provide administrative support to the Waterloo 200 legacy project.