Ralph Roberts

Back in June, I wrote a blog for the Age of Revolution project that detailed my visit to the Bowes Museum in County Durham. The Bowes Museum is one of the University of Kent’s partner locations, and part of its collection is a series of painting, prints, and objects related to Napoléon and the Napoleonic era. During my first visit I met with the museum’s Education Co-ordinator, Julia Dunn, to devise a workshop that could be delivered at Bowes for upper key stage 2 and lower key stage 3 children (approximate ages 10-12). It was hoped that we could develop a workshop that encouraged children to think about who Napoléon was and why he was an important figure, as well as to give them an opportunity to express themselves artistically using Napoleonic imagery as an inspiration. Early in November, I got the opportunity to return to the museum to see the first of these workshops in action – I was very excited to see the fruits of our labour! The workshops were led by Julia, while I was there to observe and to assist if necessary.

Upon arrival, the children were asked to colour in the French Tricolore, and to note what they already knew about Napoléon in the middle band. In most instances, this was limited to the fact that he was French, with a reasonable number of children having some awareness that he was a military figure. In short, the vast majority knew only some basic facts about Napoléon. This was perfectly understandable – I doubt that I even had that knowledge of Napoléon at age 11! It also offered a good opportunity to gauge how much the children had learned at the end of the day, to see what resonated with them and how effective the workshop had been. Interestingly, a few of them stated that he was short, which provides an example of how pervasive the myth of a diminutive Napoléon is! Once we had some idea of what the children knew about the subject, it was time to head to the galleries to begin a journey into the life of “Little Corporal”, led by Julia dressed as a “French wench” (her term, not mine, I hasten to add!).

The first stop was the John and Joséphine gallery on the first floor of the museum, which is dedicated to the founders of the museum, John and Joséphine Bowes. Before learning about Napoléon himself, the children were able to find out why there was a museum in Barnard Castle that had some pictures and objects related to a French political and military leader. It helped to provide context for the children’s visit to the Bowes Museum, and to give an indication that Napoléon’s importance and influence is widespread, including within the United Kingdom. As an aside, one of the rooms in this part of the museum contains a fabulous series of paintings by Nicholas Gabé based on the French Revolution of 1848. Though not a particularly well-known artist, Gabé captures the spirit of the subject brilliantly: his work The Barricade at Porte St Denis, Paris 1848 evokes comparison with Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, with a fearless woman leading the revolutionaries amid a pitched battle. Well worth a look if you ever have the opportunity to visit the Bowes Museum!

After learning about the museum’s founders, it was time for the children to enter the open space of the picture galleries to trace the life and career of Napoléon Bonaparte. The children were given a biographical overview of his life and times, and Julia chose some of the children to portray the key figures in the narrative. Thus, we had a Carlo and a Letizia as Napoléon’s parents, and subsequently one pupil was transformed into Napoléon, complete with military jacket, bicorne, and sabre! The first focus of Napoléon’s military career was his campaign in Italy, and specifically in Venice, as the museum’s possession of Canaletto’s Regatta on the Grand Canal provided a fantastic backdrop to the tale of Napoléon’s plundering of Venice and his denudation of the Bucintoro, the Doge’s ceremonial barge visible in the painting. Having a visual aid such as this was useful in helping the children understand that Napoléon’s ventures were on a grand scale and involved traveling to distant places to achieve his goals. To get a sense of this aspect of travel, the children marched, led by their Napoléon, into the next gallery, chanting the revolutionary slogan of Vive la France as they went. It was quite a sight to behold, and one hopes we haven’t planted any ideas in their heads should the political climate remain unstable in 10-15 years’ time!

Having finished their brief march, the children were greeted by the grand image of Napoléon as Emperor, one of Anne-Louis Girodet de Roucy-Trioson’s 26 identical portraits. With the aid of copies of some of the nineteenth-century prints held in the museum’s archive, the children were given an overview of the 17 years from Napoléon’s coronation in 1804 to his death on St Helena in 1821. It is to Julia’s credit that she was able to give the children a sense of this in one morning session, given that many historians have written entire books about this period and have still acknowledged that much more is to be said. The children were given a sense that fortunes can change in a short space of time, hence why Napoleon was able to return for his “hundred days” before being defeated at Waterloo and exiled on a remote island where any possibility of return was eliminated. At the end of the morning session, students were given the chance to sketch something from the gallery, related to Napoleon, to use for a printing exercise in the afternoon. It was fascinating to see what resonated with different individuals: whereas some were taken with the figure of Napoléon himself, others preferred more natural images such as a boat on the ocean, similar to one that would have taken Napoléon to his final resting place.

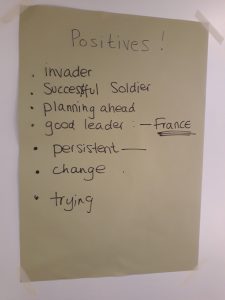

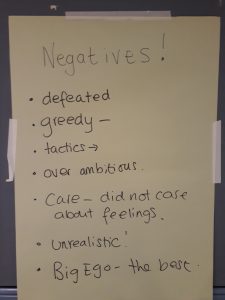

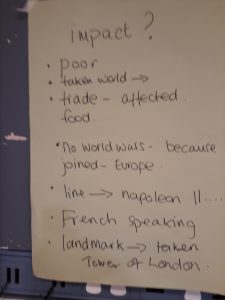

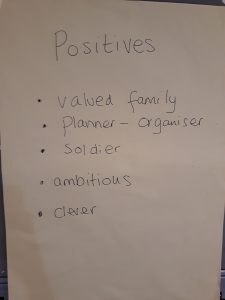

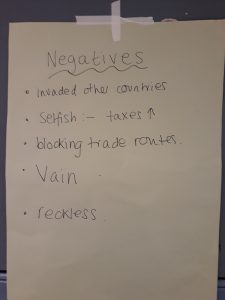

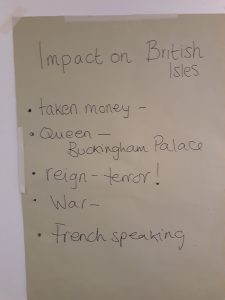

After lunch, Julia led a discussion on what the children thought might have happened had Napoléon been able to launch a successful invasion of Britain and incorporate it into his empire. This encouraged children to think about what it might have been like to live in a state occupied by Napoléon, and to consider how our own national history has been shaped by the fact that this did not occur. While counterfactuals are contentious in academic history, for students of this age it was ideal for encouraging critical thinking about the importance of events and how our modern world is shaped by causality. One pupil in the first group made the link between Napoléon’s endeavours and the subsequent world wars, and how the Europe that Napoléon left behind was influenced by him and how it might have altered had he been able to invade Britain. For somebody 10-11 years old, this was a fantastic point to make, and is a testament to how Julia’s engagement with the topic had influenced the children in attendance. The discussions also brought up other questions about what it means to be British, and how these things might be affected by a figure such as Napoléon. It was great to hear the students come up with abstract ideas based on a topic that most knew very little about beforehand, and that is a testament to Julia’s delivery, the skills they have developed in their schools, and their own natural inquisitiveness.

Before the final activity, the students were asked to write down everything they could remember from the workshops, so that we could compare what they knew by the end of the session with what they knew coming into it. Most of the children were able to recall a good number of details about Napoléon’s life, with those pertaining to his family and their roles in developing and maintaining the Empire being commonly recalled. The children wrote their recollections on the back of the flags they’d made earlier – in many instances they were running out of room due to how much they’d remembered! It was certainly pleasing for Julia, their teachers, and myself to see how much they’d learned over the course of the day.

The sessions concluded with a printing exercise, whereby the children copied their drawings from the galleries onto a polystyrene plate and used paint and rollers to transpose the images onto paper that they could hang up in their classrooms at a later date, if desired. The children enjoyed the activity, and it was certainly beneficial to break up the historical elements with some practical activities. The children all produced fantastic images in the end, even those that were stuck with someone as unartistic as I am to supervise! Hopefully the finished prints have served as a fond memento of the day for all the children involved.

To summarise, it was fantastic to be able to return to the Bowes Museum and witness the workshops take place, and I am grateful to the University of Kent for enabling me to go back. I would like to thank Julia Dunn for shaping and delivering the workshops, and for making them a success for the Age of Revolution project. The feedback from both schools involved was fantastic: both schools rated the workshop as “excellent”, and the teachers were pleased with the variety of activities available to the children and the enthusiasm with which they were delivered. Most of the children that attended had never been to the Bowes Museum before, so it is wonderful that the Age of Revolution project has enabled them to visit this wonderful location and see the art and the artefacts first-hand. I’m glad to say that our collaboration with the Bowes Museum is not over: we are currently planning outreach and digital elements to this project, to be developed and delivered in the first quarter of next year. I am very much looking forward to working with Julia and her colleagues on these aspects of the project; another Kent student, Will Jarvis, will be involved, and we’re both looking forward to what we can achieve in partnership with the Bowes Museum. If we can hit the same heights as the workshops have, I should think we’ll all be delighted!