In addition to keeping the Templeman Library a welcoming place for all, our Learning Environment Assistant Christine Davies has been exploring fashion in our collections this year! We hope you enjoy this blog post by her – and look out for details of rescheduled events when we’re open again.

I am by nature whimsical and self-indulgent, and not generally inclined to resolutions that champion achievement from self-deprivation. And yet, on January 1st, 2020, I resolved not to buy any new clothes for a whole year. I have, like many others, been cluing up on the subject of sustainability in the fashion industry and if you haven’t already seen it, I can recommend Stacey Dooley’s ‘Fashion’s dirty secrets’ documentary released last summer and still available on BOB. However, I love clothes. I have always been fascinated with the creative and complex possibilities that clothing affords, for self-expression, negotiation, transformation. I enjoy the lure of fashion, but also take delight in ignoring its dictates with regard to my personal wardrobe. Make no mistake, I fully intend to return to the high street next year, just hopefully better equipped to make more ethical and considered choices. However, to mitigate my material loss in the meantime, I have been spending some time browsing the fashions of the past, and discovered a veritable boutique in our Special Collections & Archives. Since Covid-19 has put a temporary stop to my reading room visits, I thought this would be a good opportunity to take stock and share some of my favourite finds with you.

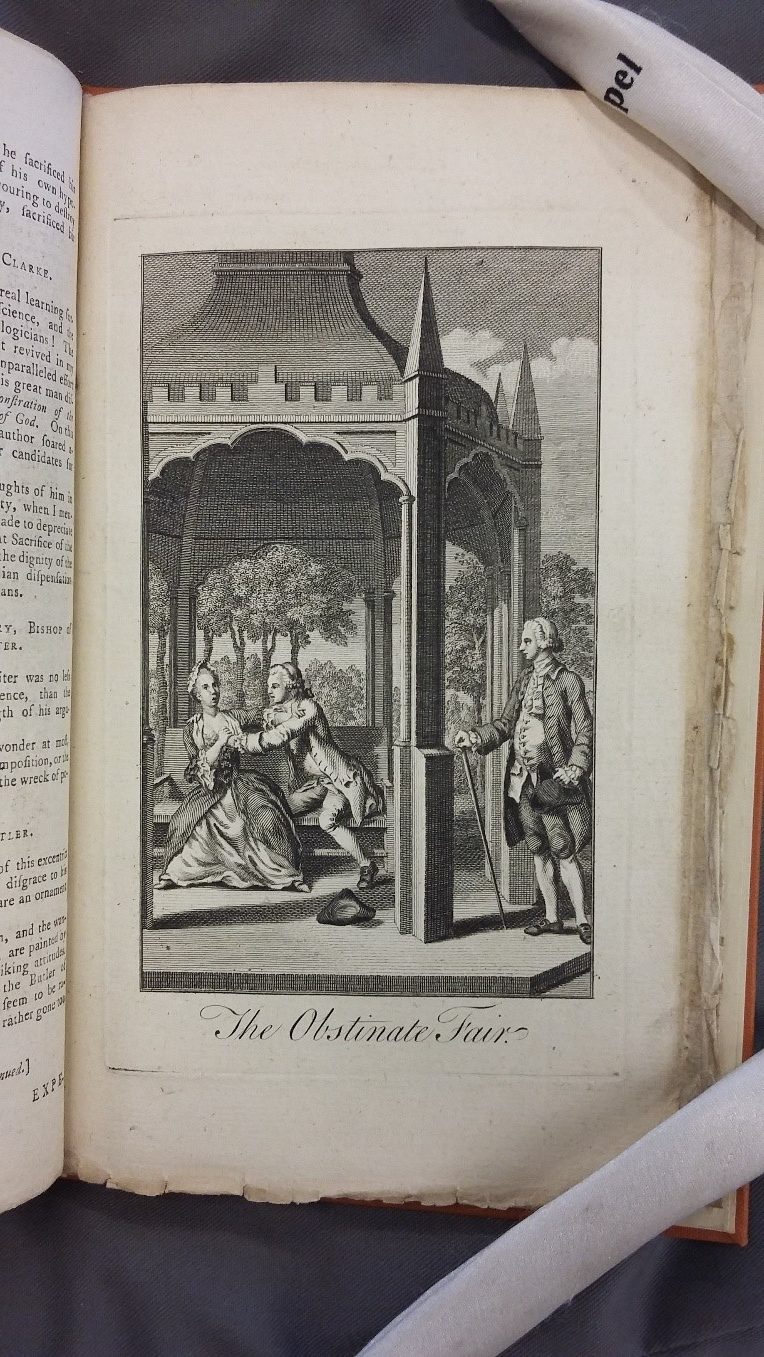

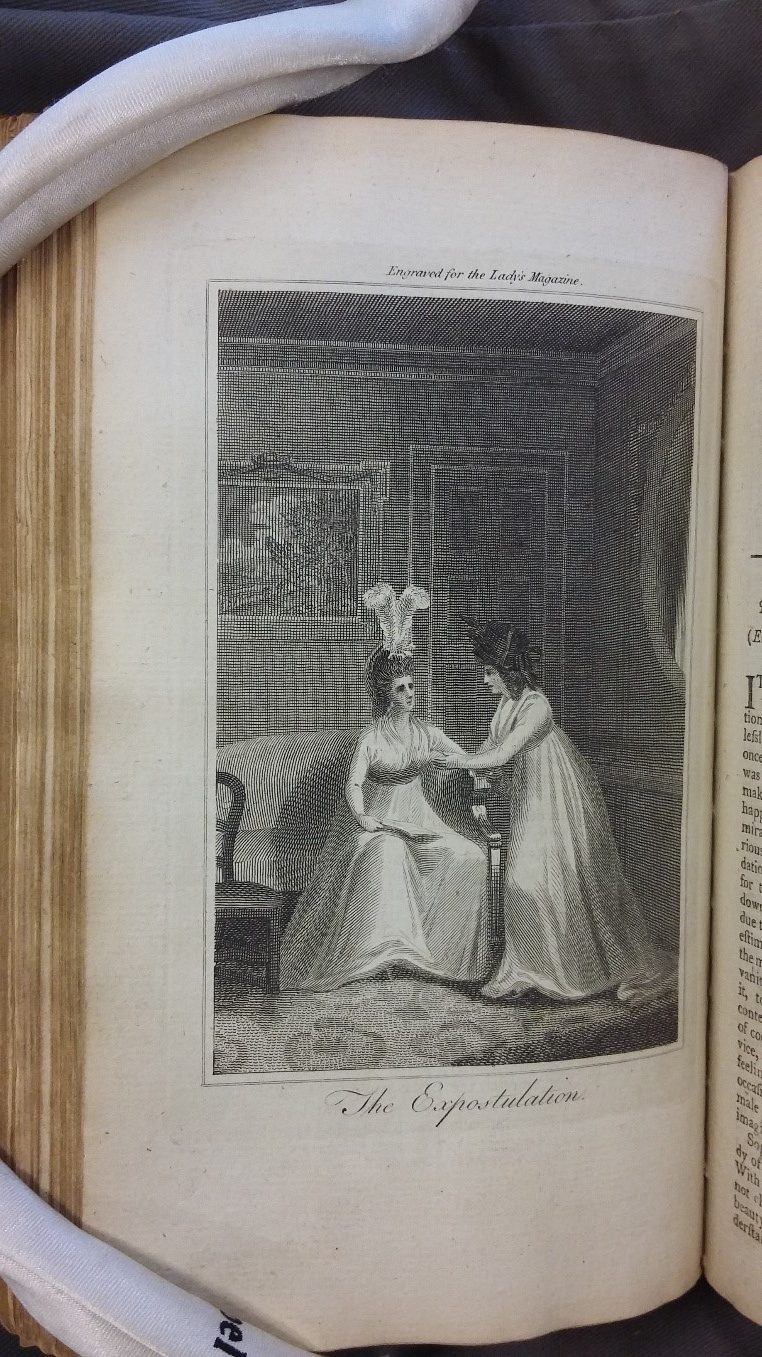

The history of fashion magazines goes back a long way, and we are lucky to have two examples of the ultimate trend-setter in this genre, The Lady’s Magazine – a monthly miscellany founded in 1770 that, from its inception, supplied readers with embroidery patterns and pilfered reports on fashions worn at court and in Paris. Special Collections has a rare single issue of The Lady’s Magazine for October 1771 and a bound volume for 1798, which, whilst sadly lacking embroidery patterns, nevertheless hold fascinating insights into historical dress. Another selling point for the magazine was its literary content, and each issue was illustrated with a monochrome copperplate engraving that often featured subjects wearing contemporary dress. As we can tell from figs. 1 and 2, 27 years can make a considerable difference – just notice the rising waistline!

For those interested in further contextualising the development of The Lady’s Magazine, you can access the entire run digitally on Adam Matthew. Also, check out Professor Jennie Batchelor’s blog for an exhilarating and in-depth discussion of the magazine, including its fashion content.

Moving into the nineteenth century, Special Collections also has some wonderful copies of La Belle Assemblée (vols. 5-11, 13, Jan. 1812-Jun. 1815, Jan.-Jun. 1816) and select issues of Le Monde Élégant, or the World of Fashion (nos. 455, Nov. 1861; 460, Apr. 1862; 461, May 1862; 473, May 1863; and 478, Oct. 1863), publications which show us how the form developed over several decades. Since I am not an expert in this field, I will keep my observations to the examples in Special Collections & Archives, but again, you can access the complete run of these publications on e-resources like Gale.

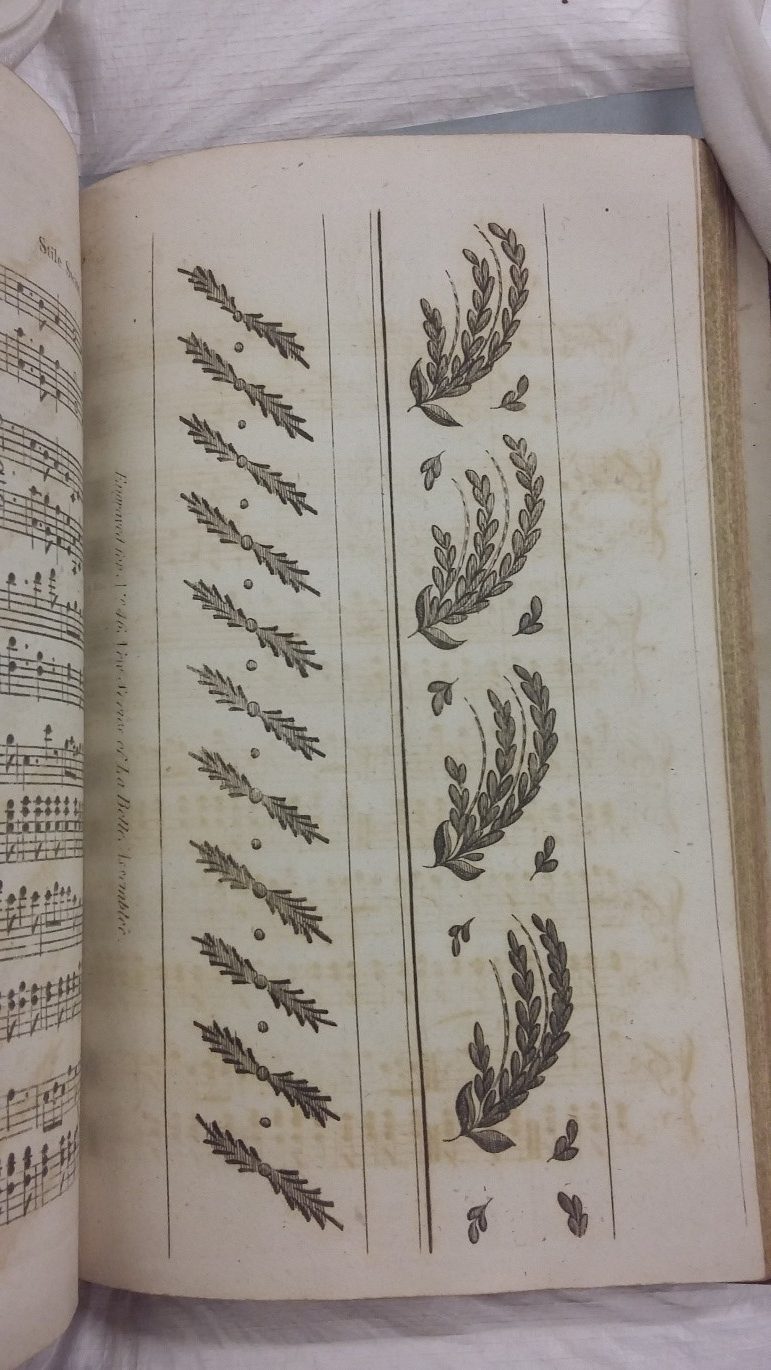

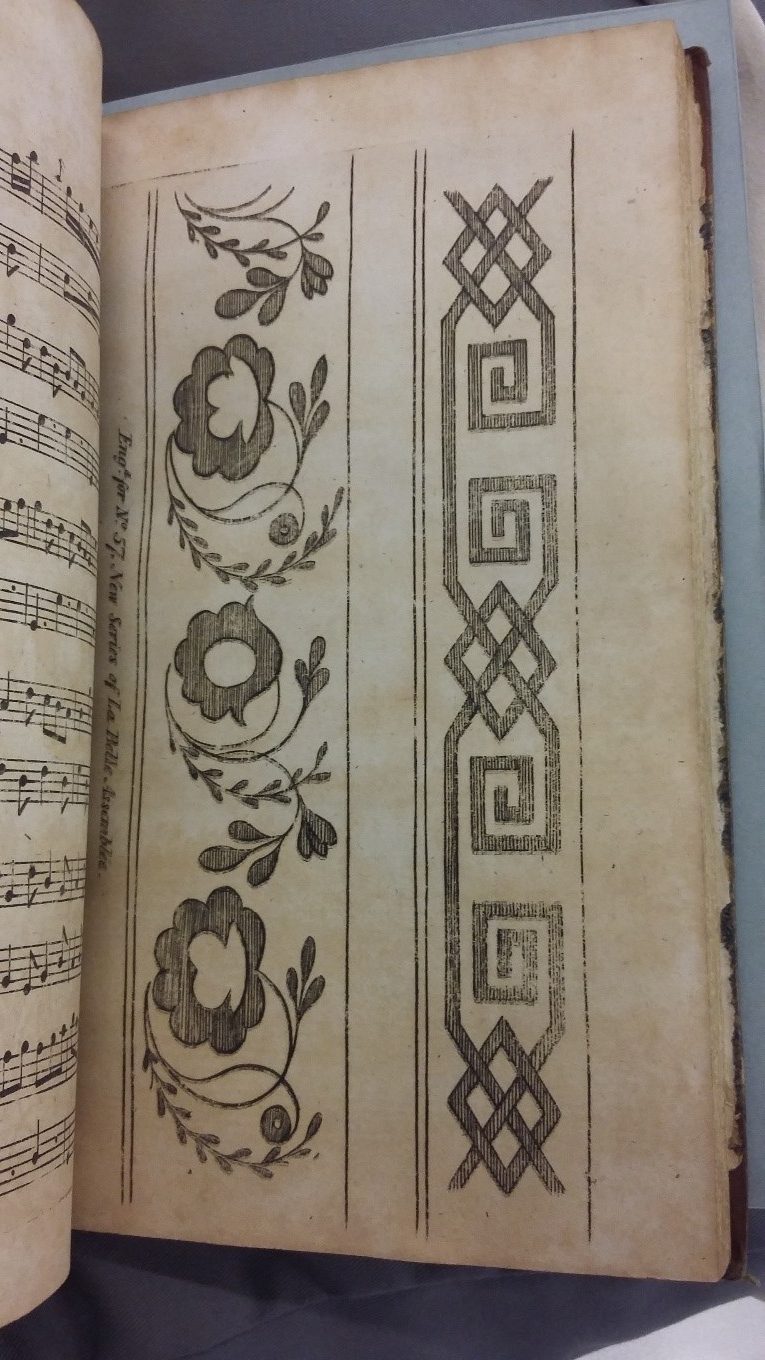

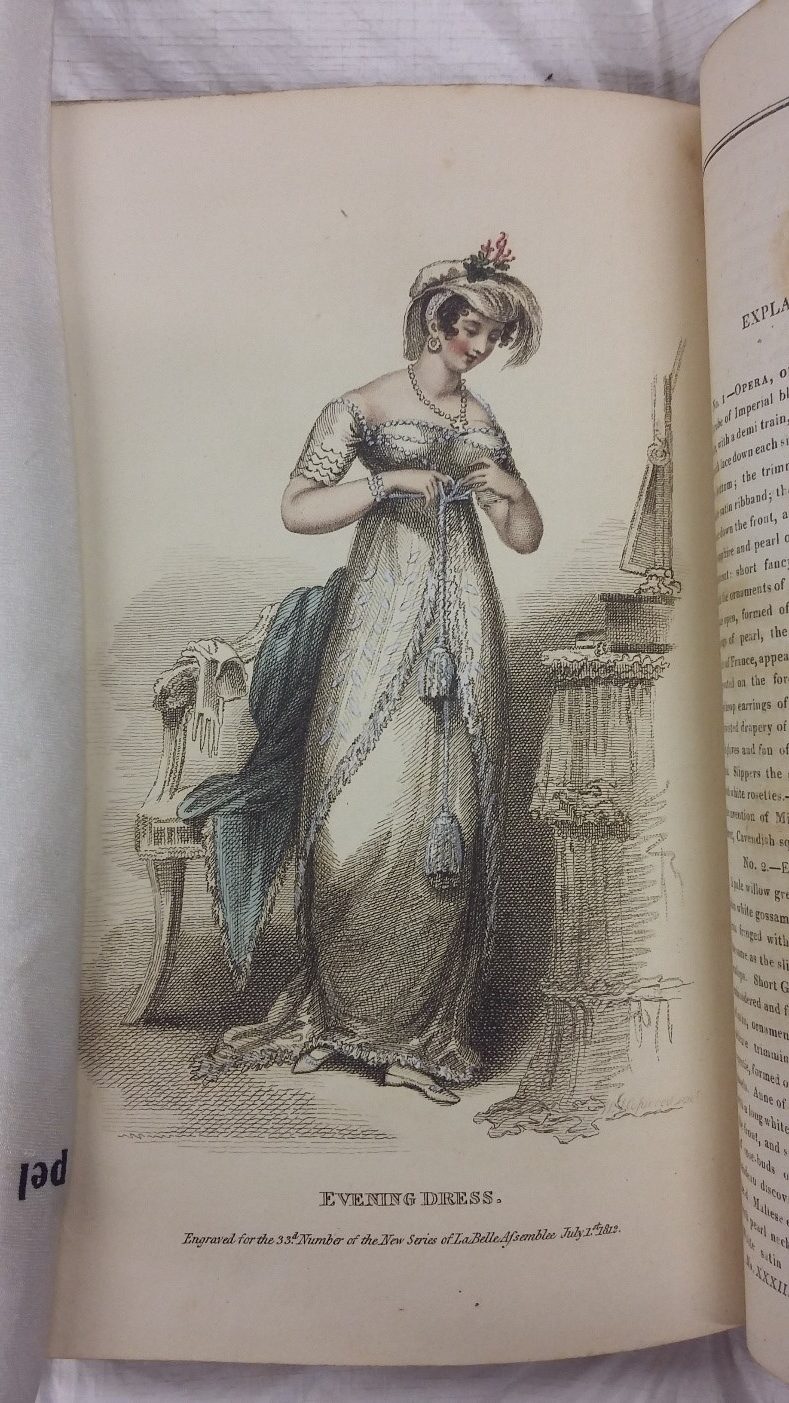

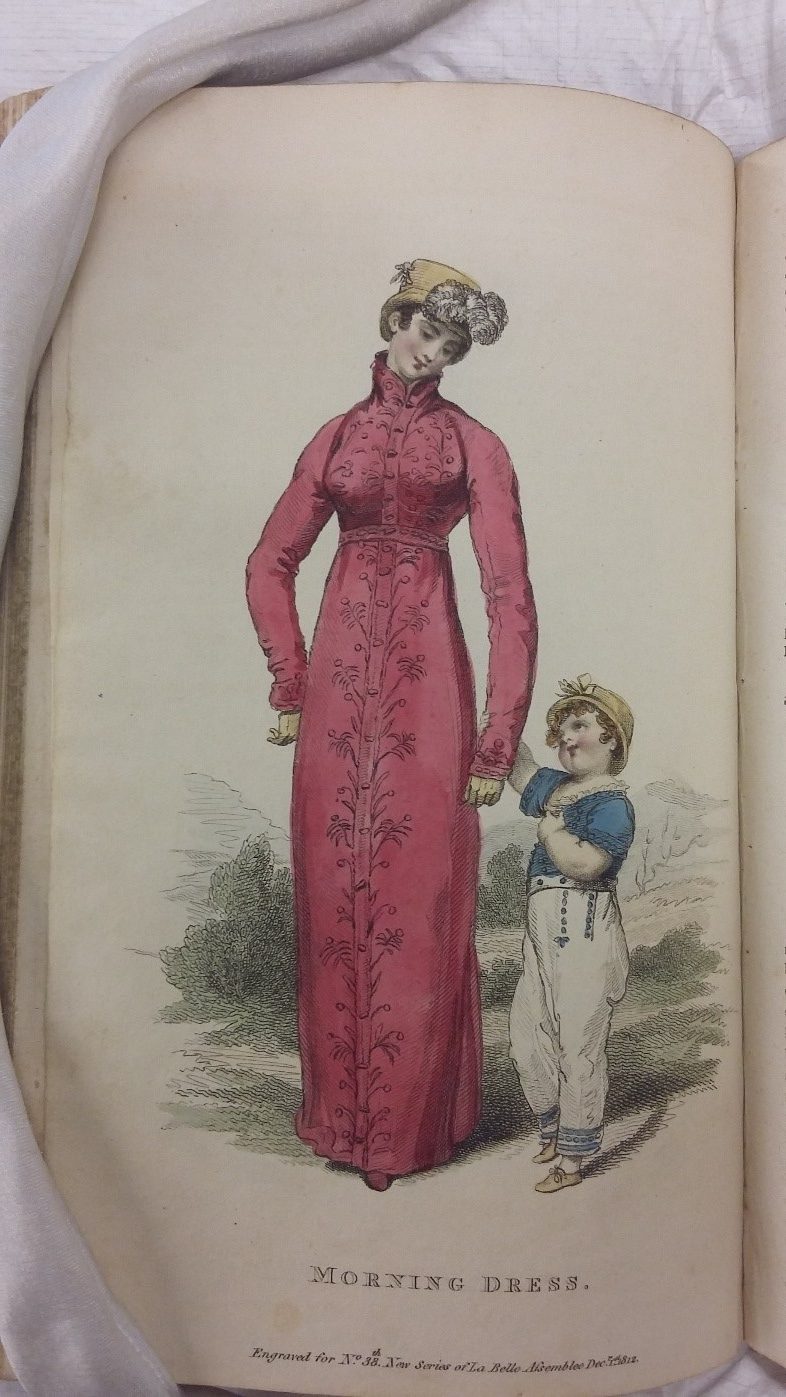

La Belle Assemblée was founded in 1806 and ran concurrently with The Lady’s Magazine; it employed a similar formula with regards to content, but swiftly invested in upscaling its fashion column to include extensive commentary and hand-coloured fashion plates. (It took The Lady’s Magazine thirty years to introduce its first fashion plates in colour, but of course this still preceded La Belle Assemblée by six). La Belle Assemblée also consistently supplied its readers with embroidery patterns in its monthly issues, and we are lucky that these survive in the Special Collections & Archives copies, providing key insights into Regency material life. In the issues at hand, the patterns typically consist of two running borders, either geometric or organic in style, which could be adapted for different garments; favourite motifs, as you can see from figs. 3 and 4, included wheat sheaves and neoclassical key patterns, or frets.

What strikes me the most, however, is the complexity of the fashion plates themselves. At first glance, they project a delightful whimsy, using colour, composition and exquisite detail to sell a lifestyle grounded in aesthetics and aspiration, and inflected, of course, with contemporary gender ideology. For the most part, the plates feature a female individual, predominantly as a full-length forward-facing standing figure – a format favoured in fashion plates generally at this time – to show both garment and figure to most advantage (think, Miss Bingley in Pride and Prejudice). I am particularly interested in fashion’s narratives of femininity, and figs. 5 and 6 are examples of plates that indisputably advocate the merits of beauty and domesticity, featuring women at their dressing-tables, pursuing sedentary activities or caring for children.

Having said this, the occasional plate was also dedicated to riding dress, (arguably the equivalent of sportswear today) featuring women with whip in hand. The plates must also be considered in the context of their accompanying commentary, which often reveals women in an alternative entrepreneurial light. In the Special Collections & Archives holdings of La Belle Assemblée, we learn that several of the featured garments derive from the creative and professional skills of the following London-based business women: Mrs. Schabner, of Tavistock-street; Miss Walters, of Wigmore-street; Mrs. Thomas, of Chancery-lane; Miss Powell, of Piccadilly; and, unsurprisingly, of a Mrs. Bell (who was successful enough to upscale from Bloomsbury to Bedford Square in the course of these few years).

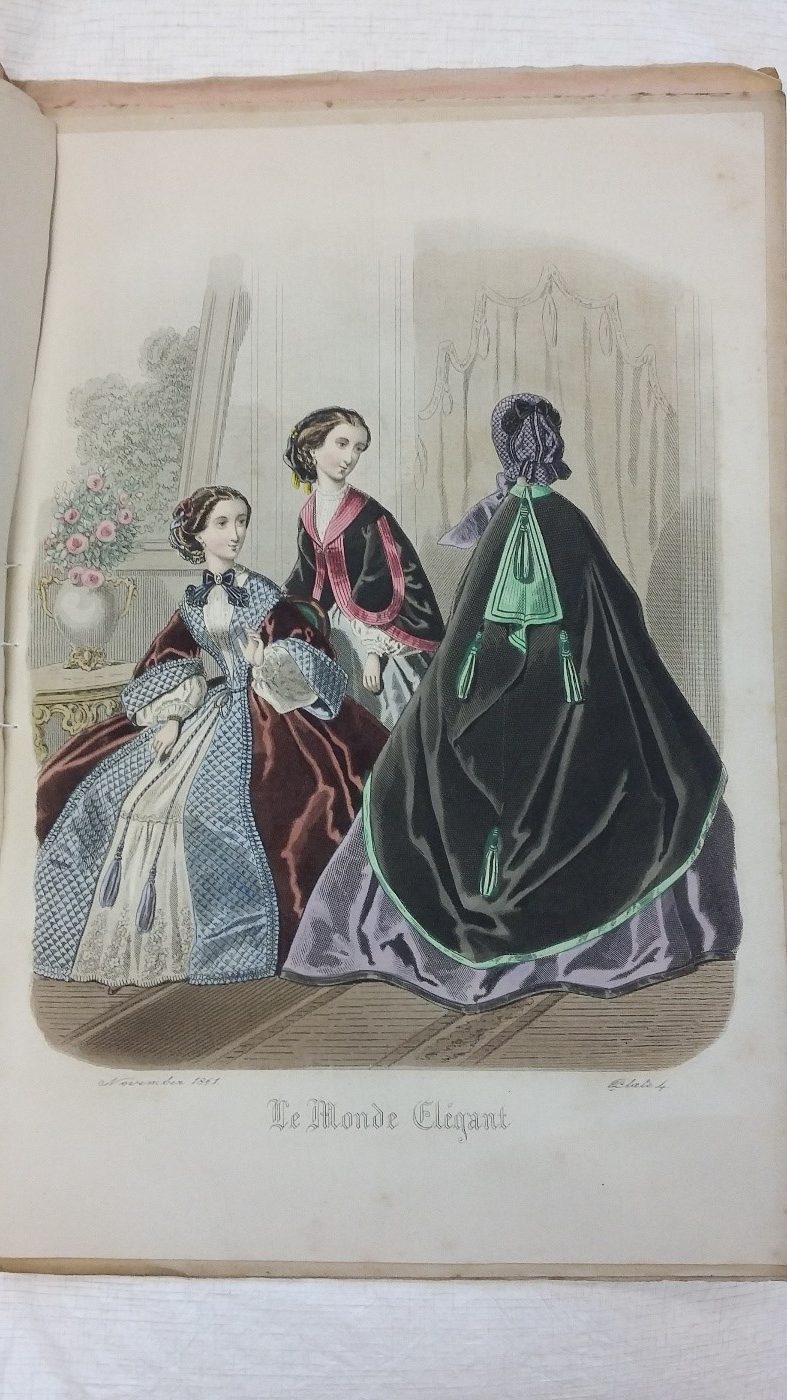

In Le Monde Élégant, the fashion plates become the raison d’être of the women’s magazine – as would be the case from hereon (I don’t know about you, but it’s rare that I actually read a column in Vogue, etc., preferring to flip through the glossy photographs, cooing and grimacing by turns). By the 1860s, Le Monde Élégant had evolved through several different titles and had several achievements, not least becoming the first magazine to introduce paper sewing patterns in the 1850s, each month enabling readers to reconstruct one of the illustrated garments for themselves. The magazine also pointed out how readers could make variations with the patterns, to suit different tastes. Intended for immediate consumption – like the embroidery patterns of earlier magazines – these were an ephemeral component of the magazine, and unfortunately do not survive in the copies held in Special Collections & Archives.

Nevertheless, we can see how the magazine sought to have real material application for its readers whilst showcasing fashions that were, for the most part, unobtainable for the middle classes. The magazine supplied five plates per issue, larger in scale than those of La Belle Assemblée, of which four were in colour, consistently featuring a group of three figures, and one in black and white, covering millinery. Of the examples at hand, the figures are entirely female, though fashion magazines in Britain had started incorporating male figures as early as 1812 (yes, you’ve guessed it, in The Lady’s Magazine). Whilst there is surely a lot more that we could explore, I think for now, we should draw this post to a close. So, to end, here are my personal favourites from Le Monde Élégant (see figs. 7 and 8).

All details of Special Collections & Archives journal holdings can be found through LibrarySearch. Thanks again Christine for a wonderful blog!