Written by Matthew Crook, student on HI6062: Dynasty, Death and Diplomacy – England, Scotland & France 1503 – 1603

Holinshed’s Chronicles is arguably one of the most important history books to have emerged from the Elizabethan era. Made up of two volumes, Holinshed’s twin books offer a fascinating insight into both early modern history and sixteenth-century printing; they also provide an understanding of how the people of the Tudor period viewed their own national past. The Chronicles were printed many times, and the Templeman Library’s Special Collections and Archives currently holds a copy of the 1587 edition of the second volume—it is this version that that will be discussed here.

Perhaps the most surprising fact about the Chronicles is that Holinshed was not the man who dreamt them up. Though he would later give his name to the work, Raphael Holinshed was really a secretary hired to help the project’s originator—Reyner Wolfe, a Dutchman who arrived in London in 1533.[1] Wolfe appears to have been an extremely ambitious man, as he originally planned for the Chronicles to cover the histories of ‘every knowne nation’, a desire which would prove to be far more difficult than he had perhaps imagined.[2] It would seem that Wolfe was naïve to the state of printing in sixteenth-century England, and his printers were quick to point out the impossibility of his plan. Even with Holinshed on board to help with the workload, Wolfe was forced to accept that the book would need a very serious scaling back to be feasible. Ultimately, the decision was made to focus the Chronicles on Great Britain alone, telling the histories of ancient England, Scotland and Ireland in the first volume and England’s royal lineage in the second. This, it would seem, was felt to be a far more manageable task than a complete international history.

Surprisingly, Holinshed was very nearly not involved in the Chronicles in the first place. Originally, he had his career trajectory aimed towards the Church, rather than history writing; his biographer, Cyndia Susan Clegg, said that he was involved in the English Protestant movement until the accession of Mary I in 1553.[3] With England’s religious situation changing rapidly, he took up work with Wolfe and, when the Dutchman passed away with the Chronicles still incomplete, he took over as project manager. What this shows is the complicated nature of the book’s production—the originator died before its completion and left it to a man who was not a trained historian. Certainly, the Chronicles was not born out of easy circumstances.

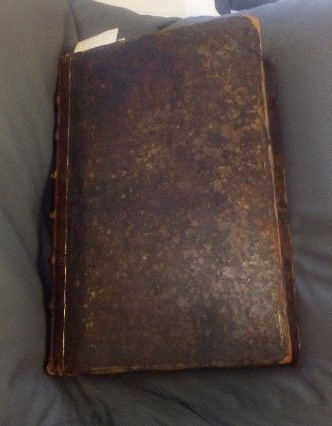

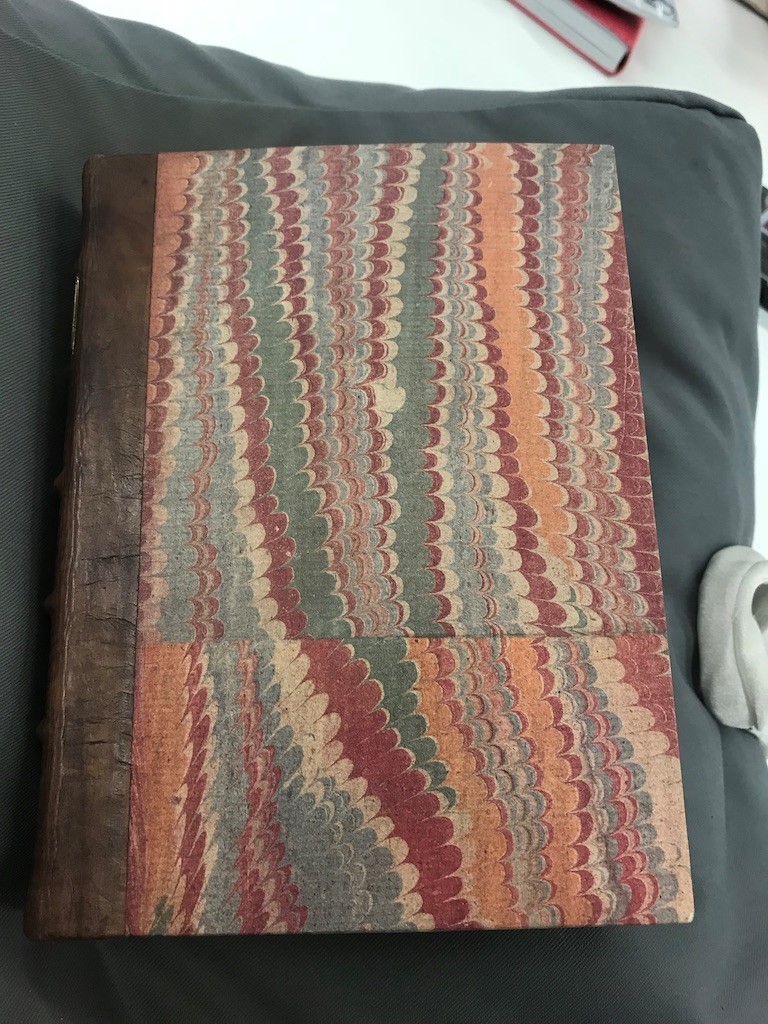

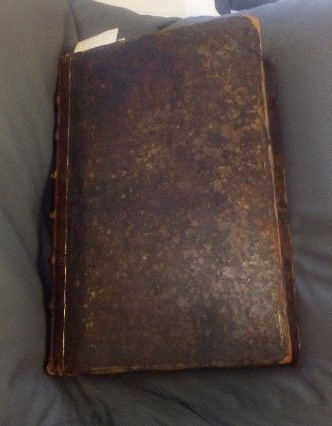

The front cover of the Chronicle—though it does show signs of age, it remains sturdy and protects the pages inside well

Nevertheless, the Chronicles remains a fascinating example of sixteenth-century literature; the Templeman’s edition is not only academically striking, however, but is also physically captivating. It’s covers are rebacked calf-over-boards and, though worn by age, it is obvious that the covers once had gilded edges. Whilst showing signs of exhaustion, these covers do show the wealth of the person who purchased the text, since books in this period were not distributed with their own covers. After all, such a book was deliberately designed for an audience that was both literate and educated, and therefore likely to be wealthy too.

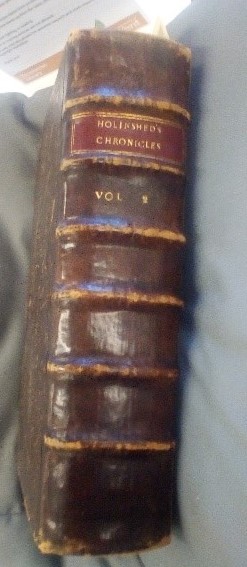

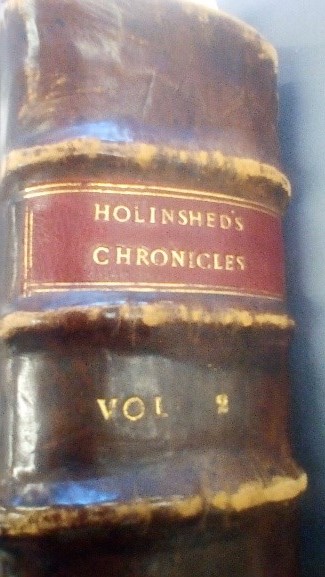

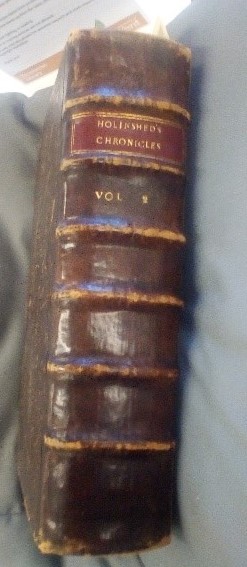

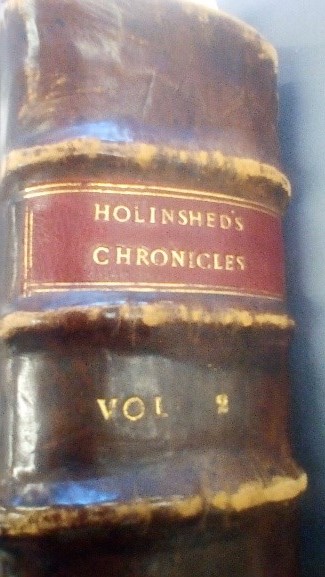

The spine for the Templeman’s copy of the Chronicles—though not original, it is undoubtedly fitting for such an impressive text.

It is, however, this volume’s patchwork nature that makes it uniquely attractive; the Templeman’s volume is a mixture of sixteenth-century craftsmanship and various repair jobs of wavering quality. For instance, the book’s spine has been very well restored, giving the text a sturdy support whilst also demonstrating the sort of gilding that is now missing from the covers. Inside the book is a different matter entirely; the first page of the Chronicles’ main body, which covers William the Conqueror, is both badly damaged and poorly repaired. The paper appears to have been torn at one point and crudely stuck back together—the technique employed, however, indicates that it was conducted towards the end of the nineteenth century; whilst this book may have needed repairing upon purchase, it does suggest the possibility that it was used a great deal throughout its lifetime.

On the spine, the title and volume number are written in gold lettering, something which reflects the gilding of the covers.

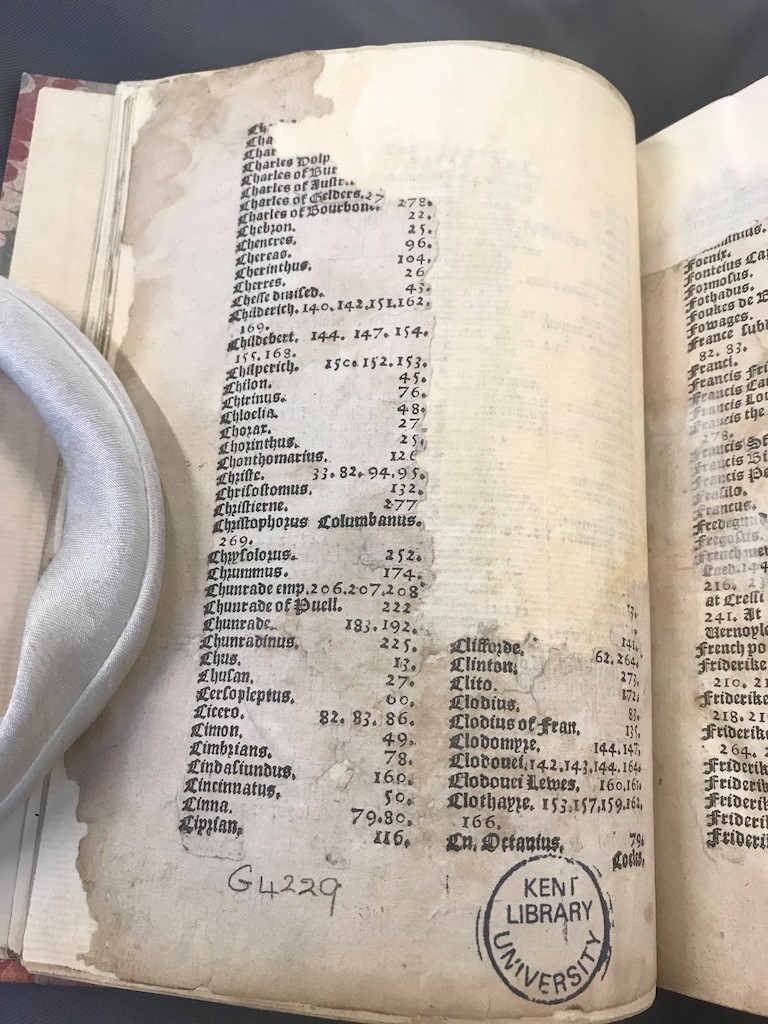

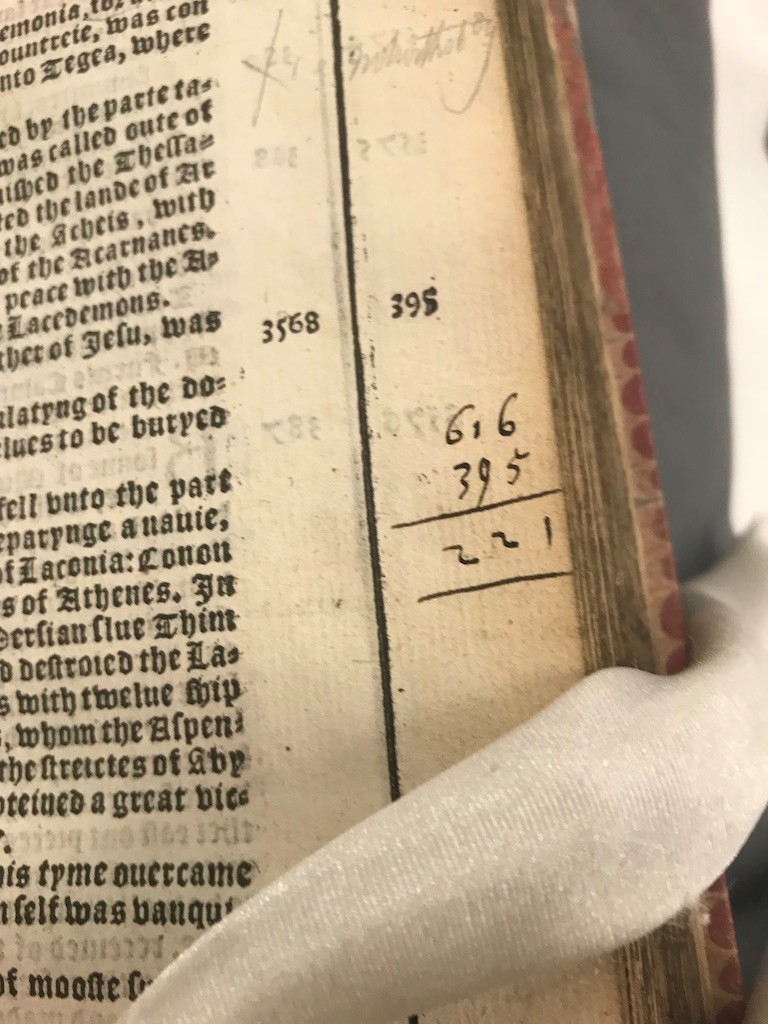

Aside from the damage and patch-up attempts, the book still maintains much of the Chronicles’ original features; among others, it demonstrates a variety of charming details that can be found in early modern printed texts. Being a book of considerable size and covering every monarch from 1066 through to the late sixteenth-century, its printers were likely aware that ease of navigation was important. Each left page has ‘An. Dom’ in the top right corner, followed by a date—since each chapter covers a different English monarch, this allowed an early modern reader to find a specific year within a king or queen’s reign without difficulty. Another interesting reader aid comes in the margin, as each paragraph has a small summation to its side that briefly describes its contents. Such a tool would be useful for anyone who used the book for research purposes; many writers used the Chronicles in such a manner, and perhaps the most famous of the text’s users was William Shakespeare. Allardyce and Jacqueline Nicholl, in their book Holinshed’s Chronicles as Used in Shakespeare’s Plays, notes that he was known for using Holinshed’s book to inspire many of his most beloved plays, including Richard III and King Lear.[4]

This image shows the inside of the book—specifically, the start of the section about Richard II. Though the book is centuries old, the print is surprisingly legible.

The Chronicles’ function as a history book is relatively straightforward; it details the lives of each English monarch in a linear fashion, with little deviation from such a structure. Curiously, however, the authors appear to have taken the chronology aspect very literally. For example, the chapter on Richard II does not end with the king’s death in 1400, but rather with his deposition the previous year.[5] At the very end, there is an authorial note which declares that, ‘Thus farre Richard of Burdeaux, whole deprivation you have heard; of his lamentable death here—after, to wit, pag. 516, 517’. The death of Richard II is only acknowledged during the section on his successor, Henry IV; whilst one would expect the deposed king’s death to be acknowledged at the end of his own section, it would seem the authors here preferred the history to be uninterrupted by time jumps. Though this does make certain chapters somewhat strange—after all, one would expect it to end with the monarch’s passing—the pathway of logical is sound and adds more to the Chronicles’ identity.

There is no doubt that Holinshed’s Chronicles is an utterly fascinating book. Not only is it contextually and academically marvellous, but its numerous printing quirks and occasional damage makes it a captivating physical object as well. Filled with all manner of oddities and unusual details, it is a treasure-trove of curiosities for any budding bibliophile.

Bibliography

Primary Material:

Holinshed, Raphael, Chronicles (London, 1587) Special Collections & Archives: Pre-1700 Collection, q C 587 HOL

Secondary Material:

Clegg, Cyndia Susan, ‘Raphael Holinshed (1525-1580?)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [accessed 31 October 2018]

Heal, Felicity and Henry Summerson, ‘The Genesis of the Two Editions’, in The Oxford Handbook of Holinshed’s Chronicles, ed. by Paulina Kewes, Ian W. Archer and Felicity Heal (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2013) 3-21

Nicoll, Allardyce and Josephine Nicoll, Holinshed’s Chronicle As Used in Shakespeare’s Plays (J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd.: London, 1927)

Pettegree, Andrew, ‘Reyner Wolfe (d. in or before 1547)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [accessed 31 October 2018]

Tuck, Anthony, ‘Richard II (1367-1400)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [accessed 31 October 2018]

[1] Andrew Pettegree, ‘Reyner Wolfe (d. in or before 1547)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [accessed 31 October 2018]

[2] Felicity Heal and Henry Summerson, ‘The Genesis of the Two Editions’, in The Oxford Handbook of Holinshed’s Chronicles, ed. by Paulina Kewes, Ian W. Archer and Felicity Heal (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2013) 3-21, p.3

[3] Cyndia Susan Clegg, ‘Raphael Holinshed (1525-1580?)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [accessed 31 October 2018]

[4] Allardyce Nicholl and Josephine Nicoll, Holinshed’s Chronicle As Used in Shakespeare’s Plays (J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd.: London, 1927), p.vii.

[5]Anthony Tuck, ‘Richard II (1367-1400)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [accessed 31 October 2018]