Hello again! Welcome to the second post in the series of our foray into the Maddison Collection. This past week has seen temperatures skyrocket but we have been staying cool in the basement of the Templeman Library, researching and caring for the treasures of the collection. Read on as we turn up the heat on this week’s topic, The Honourable Robert Boyle F.R.S.

For the record, all puns are the fault of Philip and Jo. Janee relinquishes all responsibility for them.

One of the first things we noticed when we began working on the Maddison Collection was the sheer volume of texts on Robert Boyle. He is perhaps the collection’s best represented topic. By the time we got to the fourth shelf, of the first bay we were working on, we discovered why Maddison had collected such an immense number of books focusing on Boyle: he had written his own book on the topic, one of the first full biographies on Robert Boyle! A little more research unveiled that Maddison had in fact also written around twenty articles on Boyle, as well as a second book on the subject and had been gathering material for over twenty-five years (Maddison, The life of the Honourable Robert Boyle, viii).

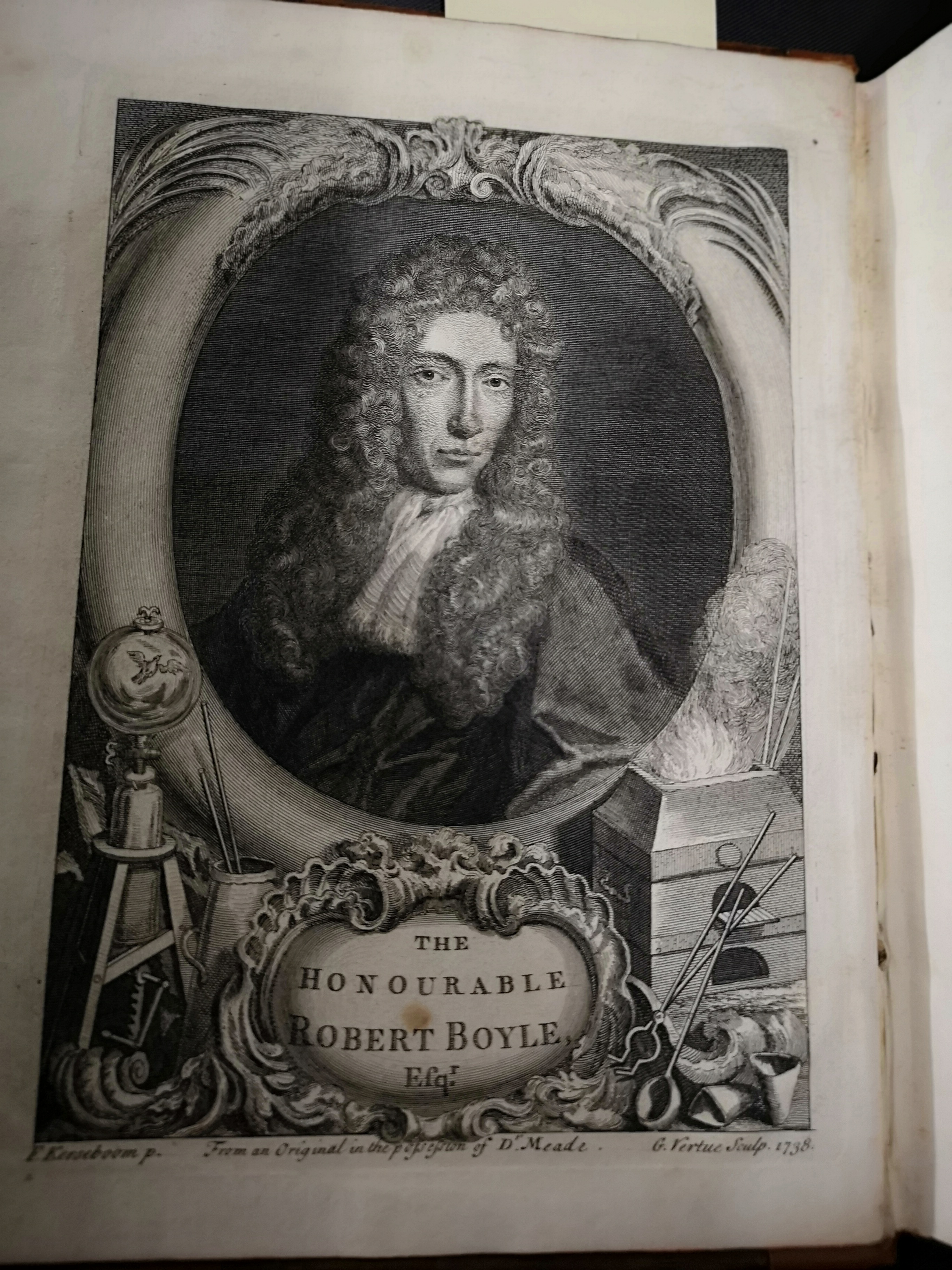

Boyle is often considered to be the ‘Father of Chemistry’ and is most well-known for the scientific principle named after him. Boyle’s Law states that the pressure of a given quantity of gas varies inversely with its volume at constant temperature. To this day we are taught about Boyle’s Law in science classes, and so it was a surprise to find that between the mid eighteenth- and early twentieth-century there was very little academic scholarship conducted on Boyle. As Maddison notes in the Preface to his book, Thomas Birch’s volumes on Boyle, written in the eighteenth century, have ‘served as the basis of all subsequent accounts of Robert Boyle, wherever they have been published, right down to the present day’ (Maddison, viii).

It was only after the Second World War that there was a major shift in Boyle scholarship. One such scholar, Marie Boas was particularly well known for her research during this time period, publishing two books and a series of articles about Boyle. Boas’ work provides a detailed analysis of Boyle’s aims and achievements and both of her books can be found within the Maddison collection.

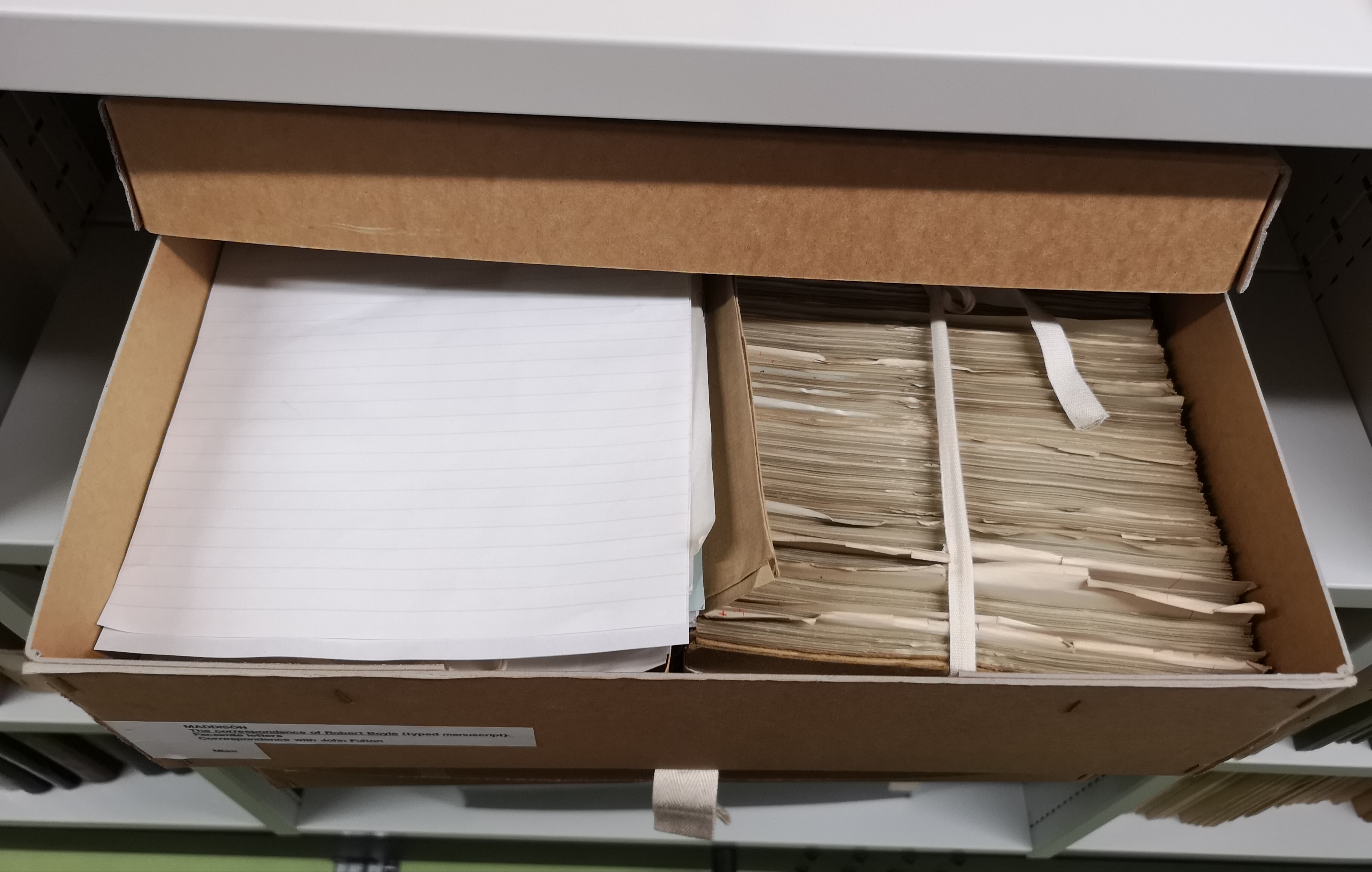

While Boas focused on Boyle’s academic achievements, Maddison had an all-encompassing interest in Boyle. Within Maddison’s biography he dedicates sections to discussing Boyle’s appearance, life and family, alongside his published writings and contributions to the scientific community. When looking through the collection it becomes clear that Maddison was able to discuss these things in depth due to his extensive research. Amongst books authored by Boyle and covering his interests, there are boxes of letter facsimiles copied from the Royal Society’s collection, an extensive, handmade Boyle family tree, and even a book that may have come from Boyle’s personal library.

It seems pertinent at this point to provide some brief biographical information about Boyle. More can of course be found in R. E. W. Maddison’s The Life of the honourable Robert Boyle.

Robert Boyle was born in Ireland on January 25th 1627 to one of the wealthiest families in Britain and died on December 31st 1691 in London, England. He never married, nor had any children, but he did have a number of siblings.

Of particular importance was his older sister, Katherine Jones, Viscountess of Ranelagh, with whom he lived from 1668 until her death in 1691. Lady Ranelagh is fascinating, as her interests were similar to Boyle’s. In fact, she is thought to have encouraged him to work on questions of ethics and they would consult each other on chemistry and alchemical problems.

Boyle was a founding member of The Royal Society, although he never served as its president. The Maddison collection contains many books on the Society’s history and a significant number of holdings of ‘The Notes and Records of the Royal Society’.

Boyle’s interests were far-reaching and varied. Whilst he is best known as a natural philosopher (mainly in chemistry), he diversified and covered hydrostatics, physics, medicine, earth science, natural history, Christian devotional and ethical essays, theological tracts on biblical passages and alchemy. He sponsored religious missions and the translation of the Scriptures into several languages. His most notable works include Touching the Spring of the Air and its Effects (1660), The Sceptical Chymist (1661), New Experiments Physico-Mechanical (1682) and The Christian Virtuosos (1690). This vast array of pursuits is marvellously reflected within the Maddison Collection.

Within the collection there are copies of Boyle’s most famous works, as listed above, as well as complete volumes containing some of his lesser known texts. Maddison collected books covering religious philosophy, chemistry and natural sciences, medicine, as well as alchemy and witchcraft, amongst other things. Maddison himself held a BSc in chemistry and a PhD in photochemistry and electrochemistry, but his collection shows that he, like Boyle, was capable of straddling the boundaries between disciplines. This variety results in the Maddison Collection being able to connect with subject matters beyond that of History of Science.

As a brief example, Boyle’s interest in medicine may be of interest to those studying the history of medicine or medical students joining Kent’s forthcoming medical school and wishing to know more about their predecessors. Maddison writes of Boyle’s ‘sickly constitution’ (Maddison, 219) and suggests that this prompted ‘[h]is interest in medico-chemistry [which] was further stimulated by the desire to alleviate pain and suffering of others, with the result that he was an ardent collector of recipes and seeker of new or improved remedies.’ (221)

There are ample books which could be of use to those studying early modern philosophy, history, medicine and herbalism. Others can be studied to learn more about the geography of the time, as well as the obvious link to early Chemistry and Physics. There is a strong collection of books written before 1700 within Maddison’s collection and a surprisingly large volume of books that would be of interest to religious studies scholars.

While we don’t have the time to explore all of these niches with the collection, we are able to focus on some of our personal favourites and so following in the footsteps of Maddison and Boyle, next week we will be exploring the world of alchemy. Stay tuned to learn about making your own personal philosopher’s stone!

Further Reading

Thomas Birch (1744), The life of the Honourable Robert Boyle (A. Millar), Maddison Collection (1C30)

Marie Boas (1958), Robert Boyle & Seventeenth Century Chemistry (Cambridge University Press), Maddison Collection (1C32)

Marie Boas (1962), The Scientific Renaissance 1450-1630 (Collins), Maddison Collection (19A31)

Robert Boyle (1680), The Sceptical Chymist (Henry Hall) Maddison Collection (1C1)

Mr. D*** (1688), Traittez des Barometres, Thermometres, et Notiometres ou Hygrometres (Henry Wetstein), Maddison Collection (2A5)

R. E. W. Maddison (1969), The Life of the Honourable Robert Boyle F.R.S (Taylor & Francis Ltd.), Maddison Collection (1D15)

Previously in Janee and Philip’s blog posts:

Introduction: or, how do you solve a problem like the Maddison Collection?