May 8th 2020 is a particularly notable date for us UK residents. Not only is it a bank holiday (on a Friday), but it’s also the 75th anniversary of Victory in Europe day, better known as VE Day. On the 8th of May 1945 the Allies formally accepted the surrender of Nazi Germany, marking the end of the Second World War in Europe. What better time, then, to delve back through the British Cartoon Archive to see how cartoonists marked this momentous occasion?

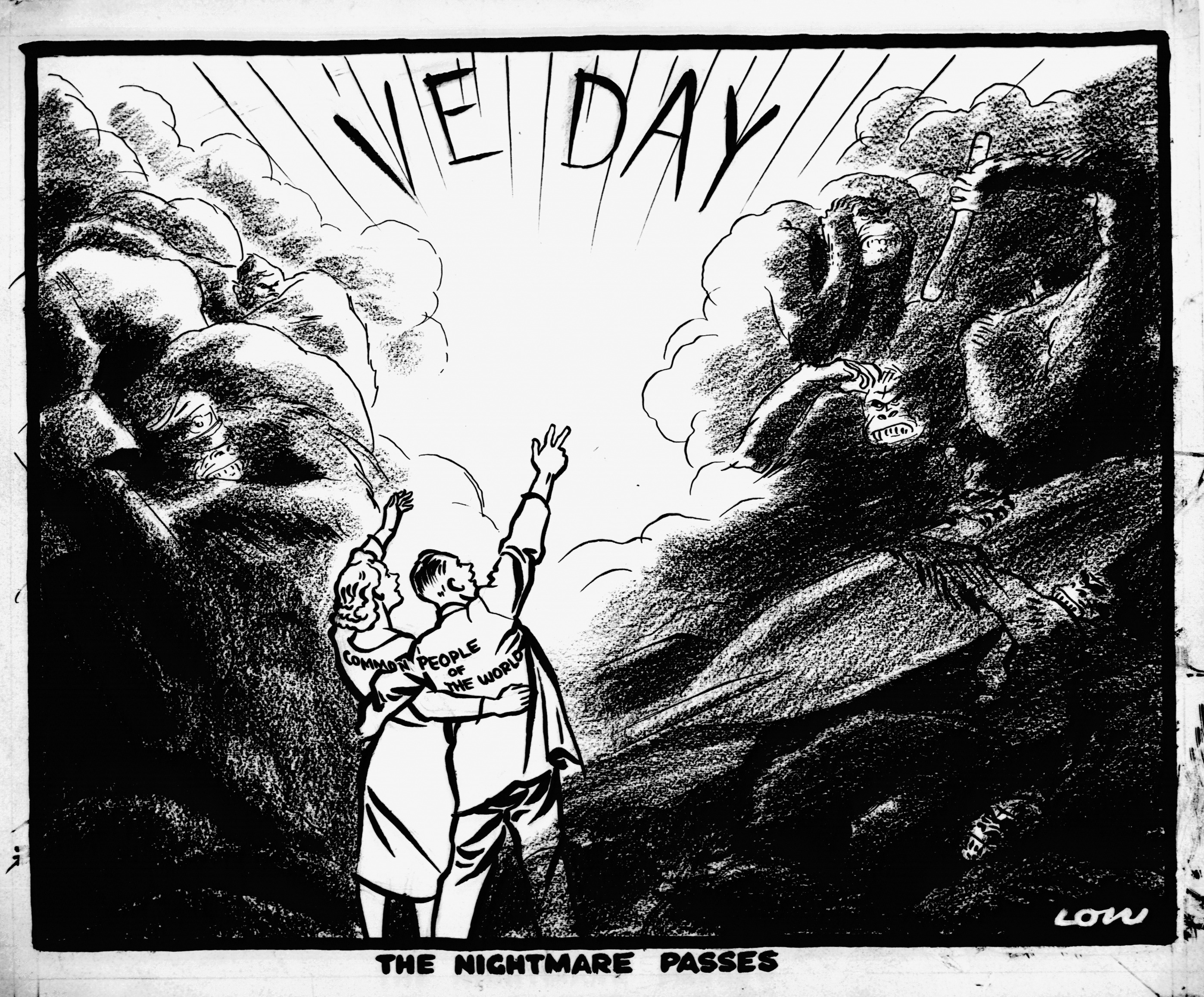

‘The nightmare passes’ by David Low is arguably one of the most famous images from VE day. Published by the Evening Standard on 8th May 1945, it shows a man and a woman – representing everyday citizens – waving as the black clouds part to let the sun in.

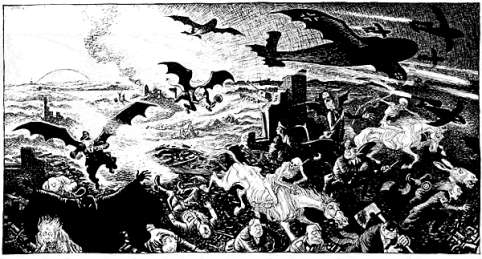

Leslie Illingworth published ‘Night passes and the evil things depart’ in the Daily Mail also on the day itself. It’s interesting to compare Low and Illingworth here – both use the natural world as a metaphor for the War, but Low focuses on depicting the general public whereas Illingworth explores the detail of the dark clouds, bringing up spooky and apocalyptic visions.

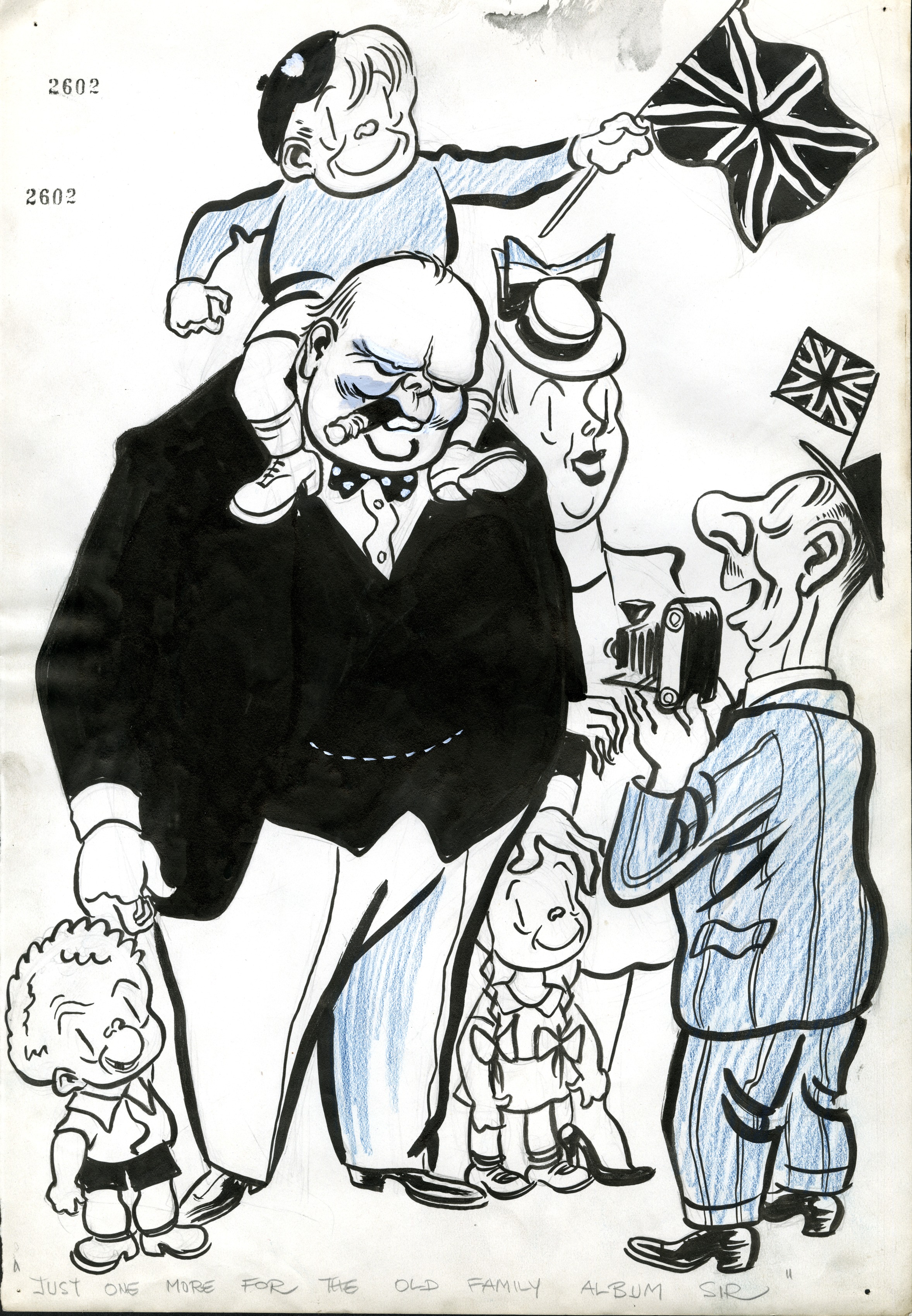

NEB (Ronald Niebour), “Just one more for the old family album sir.”, Daily Mail, 8th May 1945(NEB0247)

In contrast to Low and Illingworth, Ronald Niebour (NEB) depicts one of the most famous figures of the Second World War – Prime Minister Winston Churchill, complete with cigar in his mouth. Niebour presents a patrotic, jovial side to the celebrations here – there are multiple union jack flags and someone is photographing the scene, aware of its place in history.

Carl Giles, “…The forces surrendering will total over a million chaps…and that, gentlemen, is a good egg…”, Daily Express, 8th May 1945 (GA5444)

Carl Giles was travelling in Europe as the Daily Express’ war correspondent in 1945, so his art published during this period is more observational than his traditional style. Here Giles depicts Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, who played a crucial role in directing troops during the Second World War – both in the Western Desert campaign in Egypt and Libya and in Europe from 1944. On the 4th May 1945 Montgomery accepted the surrender of German forces in northwest Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands. Giles drew this image at Montgomery’s headquarters in Luneberg; it is thought to be one of the first sketches of the Field Marshal in action, as previously he had only been depicted in caricature.

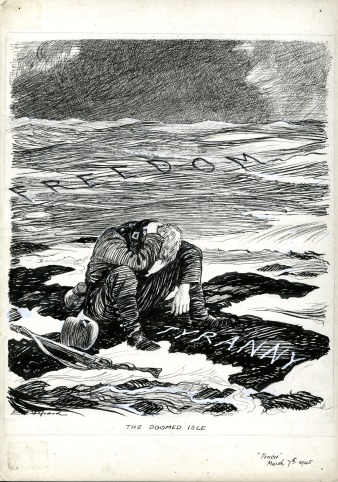

Cartoonist and illustrator E.H. Shepard’s cartoons from VE day aren’t held in the British Cartoon Archive but we couldn’t resist sharing this work, published in Punch in March 1945. Unusually, Shepard depicts a German soldier (sitting vulnerable in a stormy sea) as the tides of freedom wash in around him. The continuing nature references in these cartoons suggest that there was a feeling in 1945 (and throughout the war) that the world is returning to how it should be rather than what the Nazi party wanted to change it into.

Prior to VE day itself, cartoonists were already echoing political sentiment that the Nazi era was drawing to a close – even before Hitler’s suicide on the 30th April. Here, this drawing by David Low follows on from Shepard above to highlight the aftermath of six years of war:

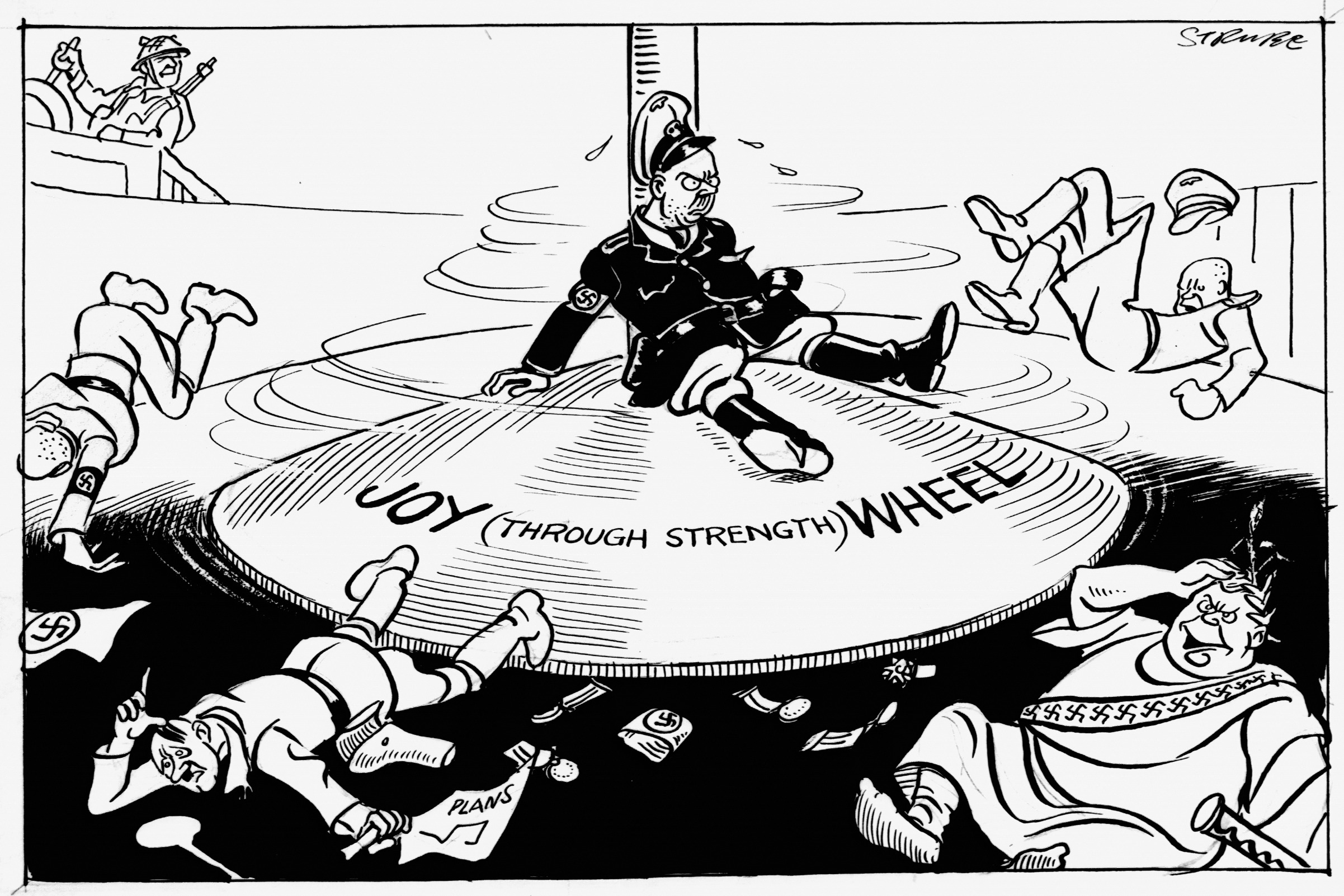

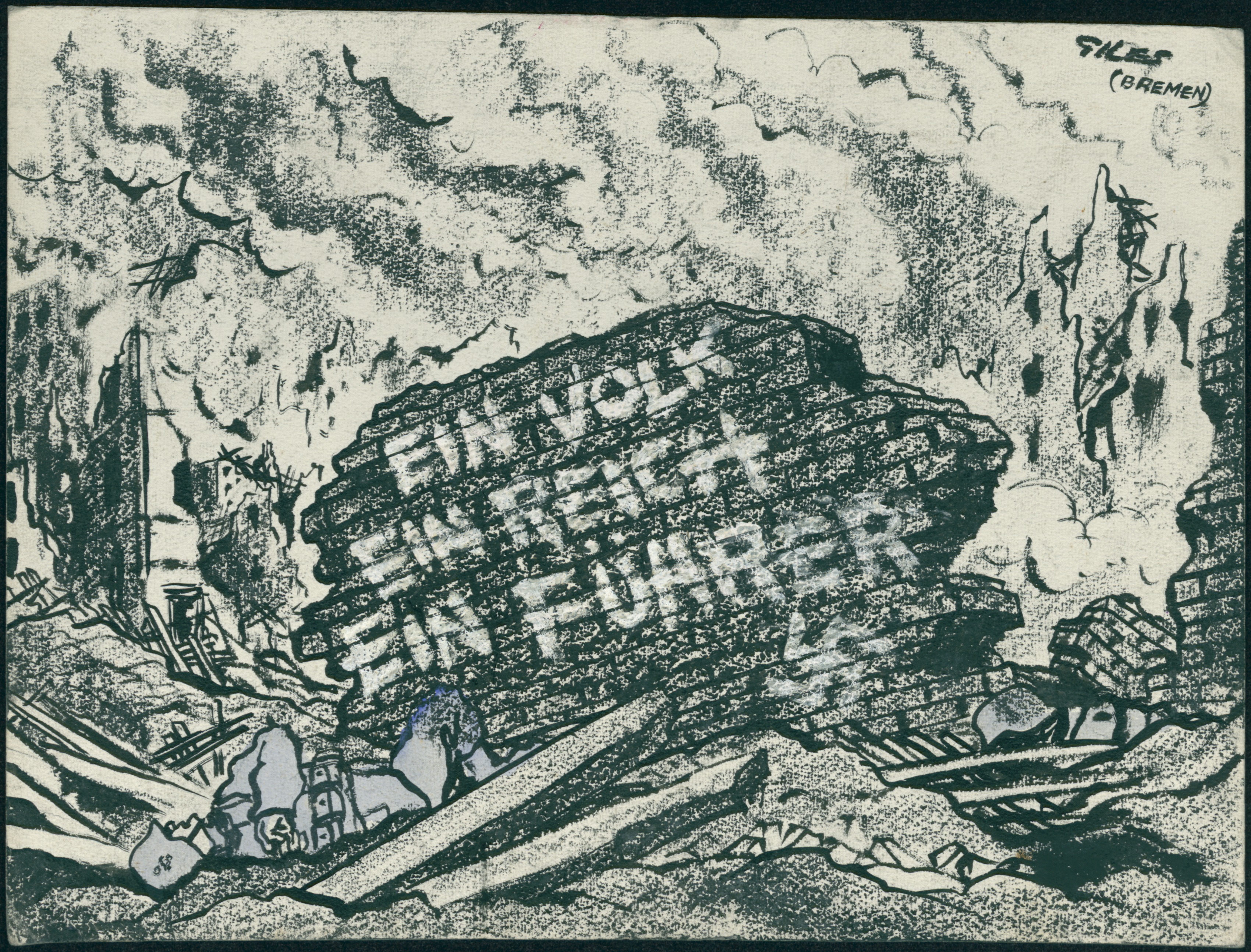

Strube takes a slightly more lighthearted approach to to the collapse of the Nazi regime, using the infamous phrase “joy through strength” here to ridicule Hitler and echo the saying “the wheels are coming off”. An interesting inclusion to Strube’s cartoon is the Roman Emperor, which could either be a reference to the mythology the Nazis sought to uphold or the political disputes which ended many Roman leaders’ reigns.Wordplay can also seen in Giles’ cartoon, published on the 29th April; here, the Nazi motto “One people, one state, one leader” is barely intact amongst the rubble of Germany:

The overwhelming majority of cartoonists praise Allied powers for bringing about VE Day, and one man in particular – as depicted here by David Low:

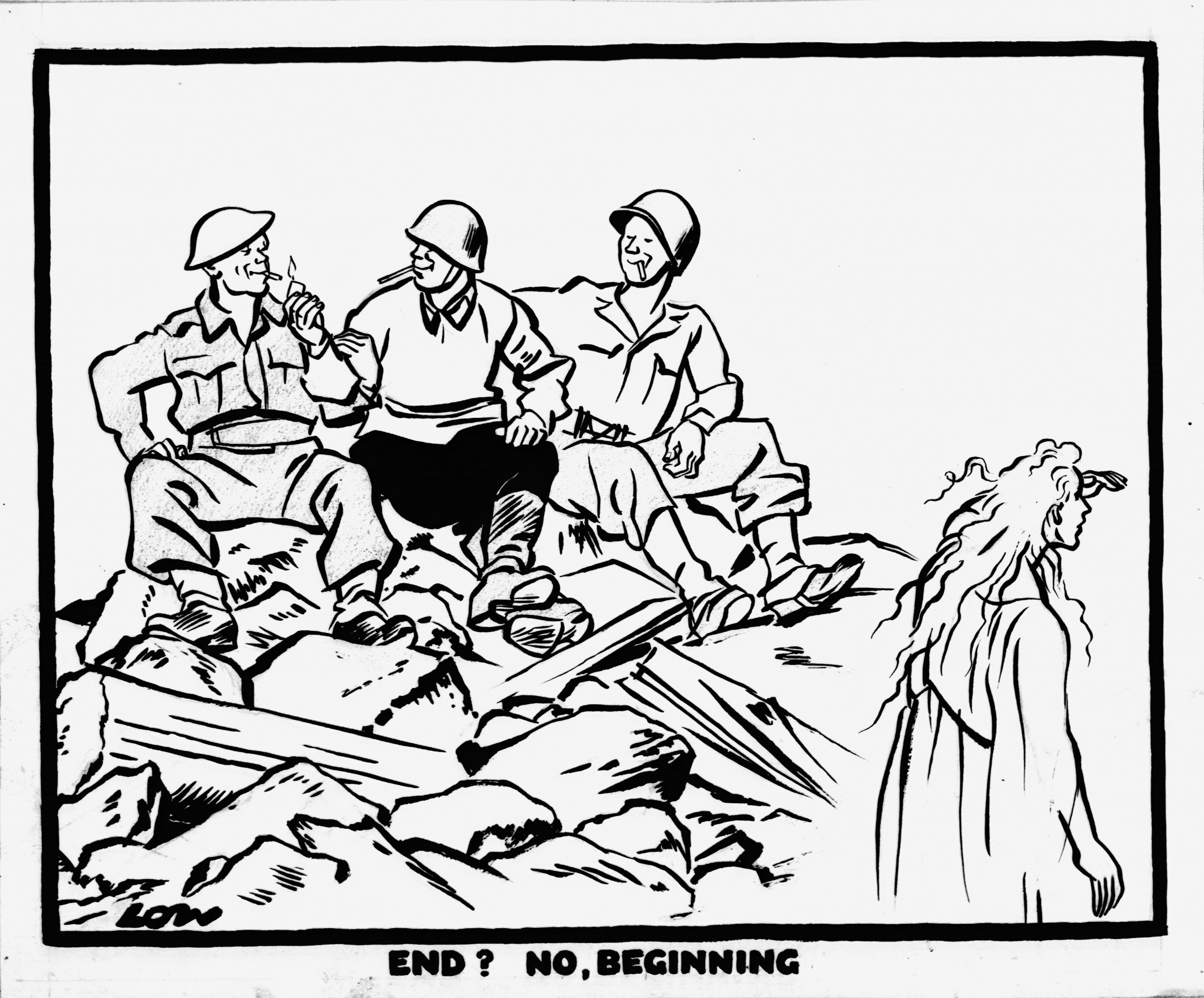

As the war ended in Europe and soldiers began to come home, many artists looked to the future. Once again, David Low summarises public sentiment best: VE Day wasn’t an end, but a beginning – well worth remembering in current times too.As ever, we could continue this exploration of VE day images for ages but why don’t you have a look? You can search through the British Cartoon Archive’s collections here. And if you’ve forgotten what exactly happened during the Second World War, don’t worry – Illingworth has your back:

![David Low, [no caption], Evening Standard, 7th May 1945 (DL2415)](http://blogs.kent.ac.uk/specialcollections/files/2020/05/DL2415-1.jpg)

![David Low, [no caption], Evening Standard, 12th May 1945 (LSE1229A)](http://blogs.kent.ac.uk/specialcollections/files/2020/05/LSE1229A-1.jpg)

![Leslie Illingworth, [no caption], Daily Mail, 1 May 1945 (ILW0898)](http://blogs.kent.ac.uk/specialcollections/files/2020/05/ILW0898.jpg)