This blog from our Centre for Philanthropy colleague and Pears Fellow, Rhodri Davies, first appeared as panels in the ‘Exploring Philanthropy’ exhibition in the Templeman Gallery in 2022.

Read on as Rhodri takes you on a whistle stop tour of the history of philanthropy!

How do we define “Philanthropy”?

“Philanthropy” is one one sense simple to define: it literally means “love of humanity”. Yet what this means in practice has proven far more difficult to pin down. The historian Benjamin Kirkman Gray argued in his 1905 book A History of English Philanthropy that philanthropy is “probably incapable of strict definition”, and many modern academics and practitioners would agree that it is an “essentially contested term”.

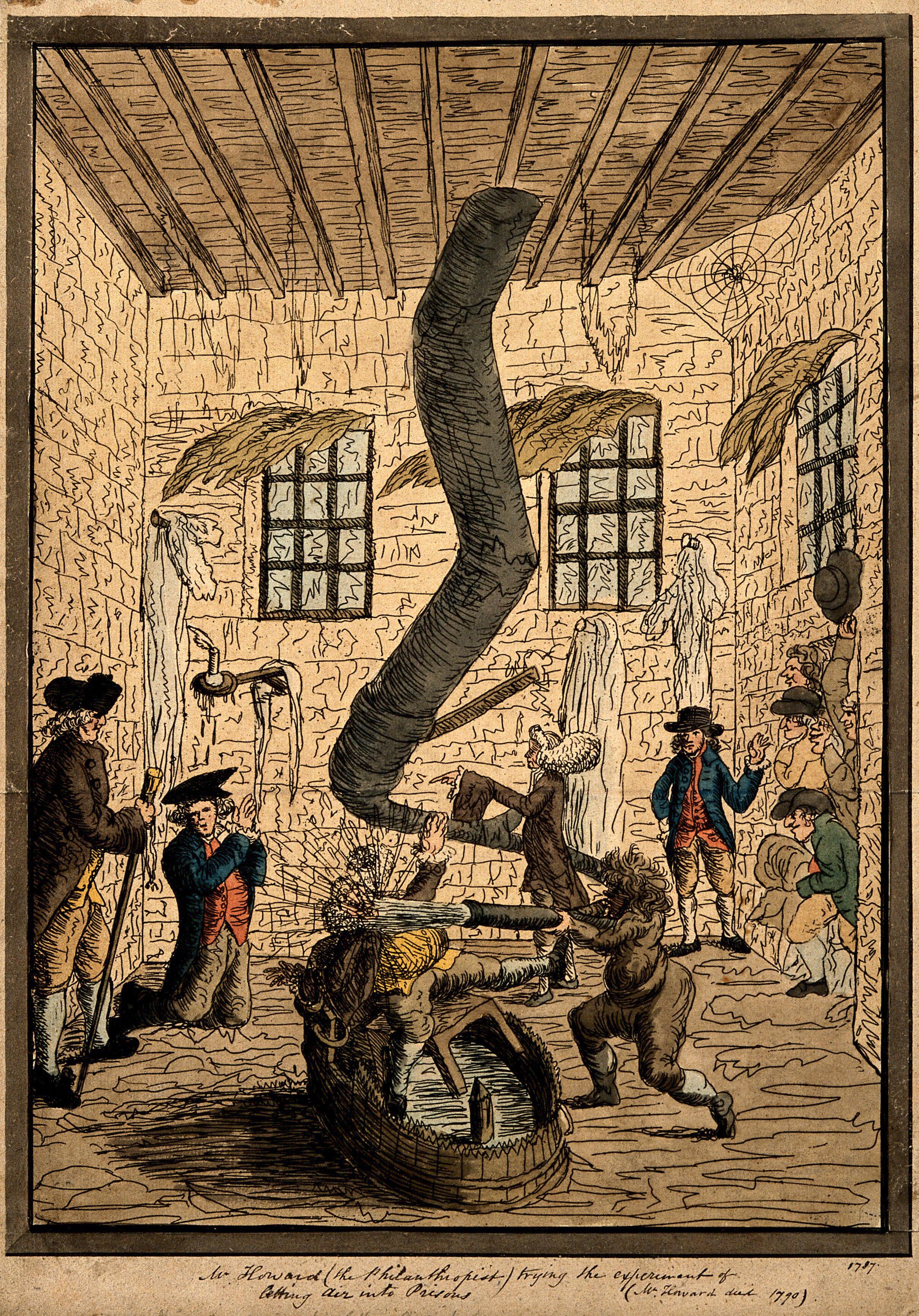

Part of the challenge is that the meaning of philanthropy has shifted considerably over time. Following its emergence in Ancient Greece (where it had a meaning significantly different to our modern understanding), the word philanthropy largely disappeared for more than a thousand years, when it was replaced by Judeo-Christian notions of “charity” and “almsgiving”. It finally re-emerged in something like its modern form in the 18th century, first in France and then in England, where it was used to refer to the prison reformer John Howard – a man who has been called “the first modern philanthropist”.

A key milestone in the emergence of the modern conception of philanthropy was the introduction in 1601 of the Statute of Charitable Uses. This did not, as it has sometimes been claimed, introduce a legal definition of charity; but its preamble did enumerate for the first time a list of purposes which could acceptably be deemed as ‘charitable’. (A list that borrowed heavily from William Langland’s 14th century dream poem Piers Plowman). This strengthened the notion of philanthropy as something that was concerned with secular problem solving, and laid the foundations for the definition of charity that we still use in the UK to this day (and, indeed, in many other places whose common law has followed our own).

We might assume a link between philanthropy and giving money, but this has not always been the case. Many of the celebrated “philanthropists” of the 18th century were men like John Howard or William Wilberforce, whose primary tools were campaigning and political influence. It was only in the 19th century, during the Victorian era, that philanthropy gradually came to be more associated with the idea of wealthy individuals giving money. This was cemented in the late 19th and early 20th century with the emergence in the USA of a new breed of ultra-wealthy industrialists like Andrew Carnegie, John D Rockefeller and J. P. Morgan – who were vilified by some as “robber barons”, but were celebrated by others for the scale of their giving. These Gilded Age mega-donors established a new template that continues to shape our understanding of philanthropy even today.

Credit: John Howard bringing water and fresh air into a prison in order to improve the conditions for the inmates. Watercolour. Wellcome Collection: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/kp2dxsex

Religion and Secularisation

The relationship between religion and philanthropy is deep and long-standing. For a long time the two were inextricably linked, as virtually all giving was guided by religious teaching and done via religious institutions. However, the Reformation in 15th Britain – which saw a schism between Catholicism and Protestantism following the decision of Henry VIII to leave the Church of Rome – together with the rise of a new form of secular humanism in continental Europe during the 16th century (epitomised by figures such as Erasmus) eventually paved the way for a new secular conception of philanthropy that was distinct from the religious almsgiving of medieval times.

This secularisation was a very slow process, however; and religious teaching continued to play a major part in motivating and shaping philanthropy for a long time. Protestant preachers and writers in the 15th and 16th centuries, keen to find new ways to distinguish their religion, often caricatured Catholic giving as “superstitious” and derided it as inferior to their own brand of “worldly” philanthropy. The poet John Donne, for instance, claimed that:

“There have been in this kingdome, since the blessed reformation of religion, more publick charitable works perform’d, more hospitals and colleges erected and endowed in threescore, than in some hundreds of years of superstition before.”

The secularisation of philanthropy only really took root with the advent of the enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries, when the arguments of influential thinkers like Mary Wollstonecraft, Emmanuel Kant and Thomas Paine led to the emergence of new views on the interplay of rights, responsibilities, charity and justice in our society.

The link between religious identity and philanthropy remained important for many, however. This was particularly true of minority groups, for whom systems of mutual aid and charity were often vital because they were excluded from the support that mainstream society offered. This was the case for the many dissenting groups of Protestants- including most notably, perhaps, the Quakers; whose willingness to combine commercial success with a strong habit of giving saw them produce many celebrated philanthropic families such as the Cadburys and the Rowntrees. It was also true of Britain’s Jewish community, which likewise gave rise to many significant philanthropists like Frederick David Mocatta and Baron Maurice de Hirsch.

Religion remains an important element of philanthropy to this day. Many donors, at all levels, would still cite religious belief as a key factor that motivates and informs their giving; even if the causes they focus on and the approaches they use reflect our more secular modern understanding of philanthropy.

Credit: George Cadbury, from Stead, H.F., How Old Age …. Wellcome Collection. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/nsq63wc6 Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Campaigning and Reform

When trying to define the difference between charity and philanthropy, a distinction is sometimes drawn between addressing the symptoms of society’s problems and addressing their underlying causes: with the argument being that the former typifies charity while the latter typifies philanthropy. This is perhaps too simplistic, but it does reflect a fundamental truth about the history of philanthropy: that campaigning and advocacy designed to bring about social change has long been just as important as addressing issues through the direct provision of services.

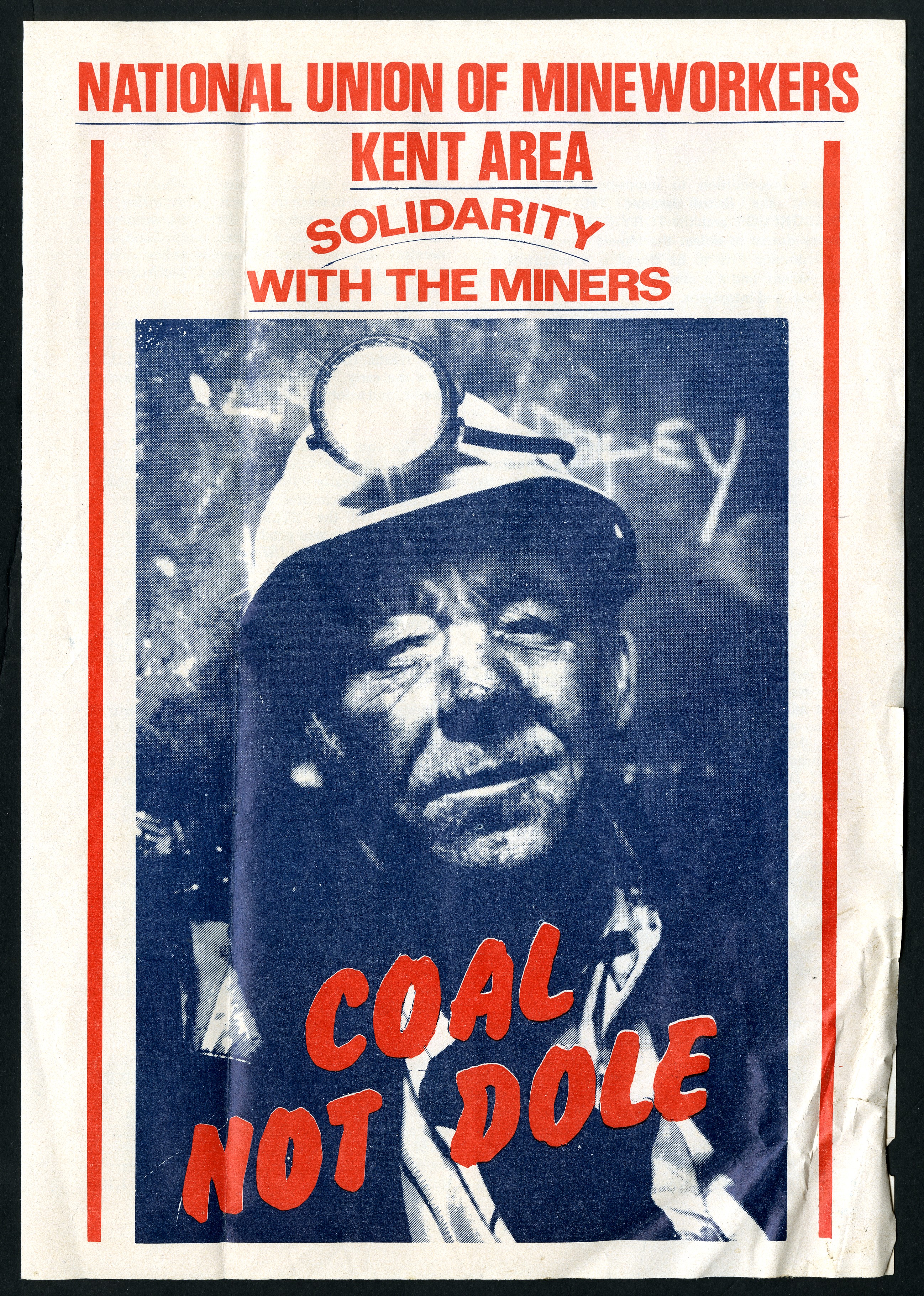

When “philanthropy” started being used in its modern form in the 18th century it was primarily applied in the context of campaigning; to figures like the anti-slavery advocate William Wilberforce or the prison reformer John Howard. And even as philanthropy increasingly came to be associated with the giving of money, efforts to drive fundamental social change rather than merely alleviate immediate suffering remained equally important.

Philanthropy has often played a particularly important role in the early stages of campaigning for new rights or freedoms, because it can provide vital support for marginalised groups and causes that have little or no public recognition at that point. Over time, further resources can be drawn in and new public and political support developed, resulting in the cause in question being brought from the margins into the mainstream and – in many cases – resulting in changes in policy and legislation. Following this template, philanthropy has helped to secure many major milestones of social progress that we now take for granted; from the abolition of slavery and the prohibition of child labour, to universal suffrage and the decriminalisation of homosexuality.

This has, of course, been far from easy. At the core of philanthropy’s role in attempting to drive social change there is often a tension between incrementalism and radicalism: between those who feel that the only pragmatic option is to work with existing systems, and those who feel that those very structures need to be torn down for real change to occur. Sometimes this tension has been a positive one; bringing both sides towards a middle ground that makes it possible to achieve real change. At other times, however, the tension between incrementalism and radicalism has proved too much and seen movements splinter.

There has also been sustained criticism of the campaigning role of philanthropy. The then-Chief Charity Commissioner wrote in 1979 that “The role of the charity is to bind up the wounds of society…to build a new society is for someone else”, and charities are still regularly told by politicians to “stick to their knitting” and “stay out of politics”. Often part of the rationale for doing so is a suggestion that charitable campaigning somehow represents an unwelcome new development. However, it is clear from history that this is far from true and that campaigning has in reality always been a vital tool for philanthropists in driving social change.

Philanthropy and Business

Philanthropy and business are sometimes presented as if they are entirely separate from one another, but in reality the lines between making money and giving it away have often been distinctly blurred throughout history, as people have found novel ways to combine profit and purpose.

As far back as 1361, on his death from plague, the Bishop of London Michael Northburgh left 1,000 silver marks to establish a fund in old St Paul’s Cathedral that would not make grants, but rather offer interest-free loans on pawned objects, which had to be repaid within one year or the goods would be sold.

In the late 17th century, meanwhile, the London merchant Thomas Firmin set up a number of projects “for the imploying of the poor”, where he ran deliberately loss-making businesses in which spinners and weavers were paid well above the going market rate. It was said that he viewed these projects as “thrifty philanthropy rather than ordinary business”. The desire to combine business and philanthropy was in fact so widespread in the 18th century that the merchant James Hodges lamented:

“Any proposals for publick benefit, at the expense of private purses, without any visible return, must probably make but a small progress”

One group notable for combining business with philanthropy were the Quakers. Many big name companies and brands that still exist to this day have their roots in Quaker-owned family companies; e.g. Cadburys and Rowntrees in the world of confectionery or Barclays and Lloyds TSB in the world of banking. Figures like Elizabeth Fry, George Cadbury and Joseph Rowntree became renowned for their giving and social campaigning; which was often inextricably linked to their commercial activities.

The creation of new accommodation and facilities for employees and their families was a prominent focus for the philanthropy of Quakers as well as other business leaders. Cadbury created the model village of Bournville to house his workers; likewise Joseph Rowntree had New Earswick, Titus Salt had Saltaire and William Lever built Port Sunlight, among others. These new villages combined decent quality housing with suitably-improving leisure amenities such as museums and gardens, and were vastly superior to the majority of the cramped housing found in larger urban areas at the time. In many cases, however, this came at the price of additional controls on the lives of workers- such as the prohibition of alcohol or the introduction of curfews.

Housing was also the focus of a different business-informed approach to philanthropy known as “percentage philanthropy” (or “4 per cent philanthropy”). This was where donors like Octavia Hill and Edward Guinness would build decent-quality affordable housing in urban areas and then charge the working classes below-market rents to live in them, so the properties would deliver some financial return and the discount would be seen as the philanthropic element.

Today there is a growing trend towards “social enterprise” or “social investment” approaches that seek to combine social and financial return. Often this is presented as an unprecedented new innovation, but in fact it is clear that there is a rich history stretching back many years of people finding ways to bring business and philanthropy together.

Credit: Elizabeth Fry. Reproduction of lithograph. Wellcome Collection: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/ghqzazrc

Philanthropy and the Welfare State

From the beginning of the 17th century, when the Tudor government somewhat reluctantly introduced Poor Law legislation, the question of whether responsibility for meeting the welfare needs of citizens should lie with the state or with private philanthropy has been at the heart of political debate for hundreds of years.

Over time, the nature and scale of social problems changed as the UK became industrialised and urbanised, and it became apparent that the State had to step into many areas. But as David Owen, one of the most prominent historians of English philanthropy, notes: The welfare role of government remained “largely supplementary, to fill such urgent gaps as might be left by the network of private agencies and to carry out its traditional obligation of relieving the genuinely destitute.”

However, from the late 19th century into the first half of the 20th century a growing body of thought emerged which saw the State as having a far more central role in providing welfare. This was realised in 1948 with the creation of the National Health Service and the wider welfare state. Philanthropy and charities had played a key role in this story, as almost every element of the welfare state as we know it reflected a need that was first identified and met through philanthropic means, but it was unclear at first what the ongoing role (if any) of philanthropy was to be. As Maria Brenton notes “a common expectation in those years at the end of the war was that the voluntary sector would just wither away.”

Some rejoiced at this idea. Labour Health Minister Aneurin Bevan, for instance, derided philanthropy as “a patchwork of local paternalisms” and thought that the move towards centralised state control of healthcare represented clear progress. Others had different views: William Beveridge, one of the key intellectual architects of the welfare state, thought that there would always be a role for philanthropy because:

“Voluntary Action is needed to do things which the State should not do… It is needed to do things which the State is most unlikely to do. It is needed to pioneer ahead of the State and make experiments. It is needed to get services rendered which cannot be got by paying for them.”

The dire predictions of those who thought philanthropy had had its day clearly turned out to be incorrect, but the creation of the welfare state did lead to a period of soul-searching in which charities and their supporters were forced to rethink what their role might be. For some organisations this meant repositioning themselves to fill in gaps in state provision. For others it meant challenging the failings of state welfare directly through advocacy and campaigning. As it became clear throughout the 1960s and 70s that universal welfare was not the panacea some had thought, organisations like Shelter and the Child Poverty Action Group emerged to bring new issues of homelessness and poverty to public attention.

The present-day relationship between philanthropy and the welfare state in the UK is complex: in addition to charities filling in gaps in state welfare, or working alongside public sector bodies to enhance state services (as many charities do within the NHS), there are also many charities that deliver services on behalf of the state through grant-funding or contractual arrangements. Perhaps as a result, the desirable balance between state-funded and philanthropic welfare provision continues to be a point of fierce debate in political discourse.

Tainted Donations

Philanthropy has, throughout the ages, generated controversy of various kinds as people object to who is giving, what they are giving to and how they are doing it. Within this controversy there is a notable recurring theme is a belief that some donations are “tainted” by virtue of where they come from because the money being given away was made in ethically dubious ways.

The question then, of course, is whether it is better to accept the gift in the hope of “putting bad money to good uses”, or to turn it down in order to avoid tainting oneself. This is a question people have been grappling with for as long as they have been giving to good causes, and opinion has always been divided. In 746, for instance, at the Council of Clovesho (a church synod attended by Anglo-Saxon kings) it was decreed that “alms should not be given from goods unjustly plundered or otherwise extracted through force or cruelty”.

Likewise in the 19th Century the Quaker philanthropist George Cadbury took a holistic view of wealth: as the historian David Ownen notes, “making money and giving it away formed for Cadbury a single pattern, and making it could be a constructive socially as giving it away. No amount of philanthropic giving could take the curse of a fortune that had been accumulated carelessly or without regard for the welfare of the workpeople who had labored for it.”

Others, meanwhile, have argued that the distinction between “good” and “bad” money is unworkable and should therefore not be an impediment to philanthropy: according to George Bernard Shaw:

“practically all the spare money in the country consists of a mass of rent, interest and profit, every penny of which is bound up with crime, drink, prostitution, disease and all the evil fruits of poverty as inextricably as with enterprise, wealth, commercial probity and national prosperity. The notion that you can earmark certain coins as tainted is an unpractical individualist superstition”.

And “General” William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army, perhaps expressed it most clearly when he (somewhat apocryphally) said “the only problem with tainted wealth is t’aint enough of it!”

Concerns about tainted donations continue to be a major issue for philanthropy. As the UK undergoes something of a reckoning with our national history in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests in recent years, many organisations – including philanthropic ones – are digging into their own histories to uncover potentially problematic links to slavery and the proceeds of colonialism, and trying to determine the best course of action to take in light of these findings. There are also concerns about current donors: the most notable example in recent years being the Sackler family, whose long-standing philanthropy has become the focus of widespread controversy as a result of their much-criticised role in creating and sustaining the US opioid epidemic.