Our discussion about The Witness for the Prosecution in its various forms focused on: differences between the mediums (radio, short story, TV, 1957 film) including of the plot’s key revelation; whether and how various characters received their comeuppance; the characters of Leonard, Romaine, Mayherne (Mayhew in the BBC TV version) and Emily French; matters of gender, class and World War I; general comments on Sarah Phelps’ TV adaptation, especially its pacing and cinematography.

Starting the session by listening to the BBC’s half hour 2004 radio version meant that we were able to compare and contrast the ways in which Agatha Christie’s 1933 short story was adapted to different mediums. Unlike the short story which reported the meeting between Leonard and Emily French and the latter’s murder in retrospect, the radio version utilised flashbacks which directly reported Leonard and Emily’s interaction; this meant that we were not relying on Leonard’s rather doubtful word (also true of the BBC TV version).

The quick pace of the radio version, with the fairly rapid switching between its micro scenes, often marked by bursts of Django Reinhardt, was especially commented on. We also noted how the main expansion of the radio version from the short story was its preface. This featured Leonard’s garrulous club-owning friend George (whom we compared to George Sanders’ character in Alfred Hitchcock’s film version of Rebecca (1940) which provided Leonard with some colour by association. References to the club also helped to establish the metropolitan London setting. Shifts within this were well evoked by sound effects: Romaine asked to speak to Mayherne outside in private and the subsequent scene was punctuated by birdsong. The time setting was established by both references to the date of the crime (in the year 1947) and by the wail of sirens.

The quick pace of the radio version, with the fairly rapid switching between its micro scenes, often marked by bursts of Django Reinhardt, was especially commented on. We also noted how the main expansion of the radio version from the short story was its preface. This featured Leonard’s garrulous club-owning friend George (whom we compared to George Sanders’ character in Alfred Hitchcock’s film version of Rebecca (1940) which provided Leonard with some colour by association. References to the club also helped to establish the metropolitan London setting. Shifts within this were well evoked by sound effects: Romaine asked to speak to Mayherne outside in private and the subsequent scene was punctuated by birdsong. The time setting was established by both references to the date of the crime (in the year 1947) and by the wail of sirens.

Discussion also focused on the ways in which the radio medium in its lack of the visual differed to the TV adaptation. This mostly involved our recognition that one of the radio actors played 2 key roles: Miriam Margolyes was recognisably Romaine as well as the part she plays to deceive Mayherne (Mrs Mogdon). While different accents and markers of class were used (we especially noted the newly named maid ‘Flora’ McKenzie’s Scottish brogue) we

Discussion also focused on the ways in which the radio medium in its lack of the visual differed to the TV adaptation. This mostly involved our recognition that one of the radio actors played 2 key roles: Miriam Margolyes was recognisably Romaine as well as the part she plays to deceive Mayherne (Mrs Mogdon). While different accents and markers of class were used (we especially noted the newly named maid ‘Flora’ McKenzie’s Scottish brogue) we  also recognised some of the actors by their voices: this meant that our knowledge of the age and appearance of some of the actors gave us particular views of the characters played. We thought Hywel Bennett as Leonard sounded older and more confident than in the TV version – as indeed did Romaine. This meant that the TV version’s revelation of Leonard and Romaine’s crimes, and the level of manipulation employed, were perhaps more surprising.

also recognised some of the actors by their voices: this meant that our knowledge of the age and appearance of some of the actors gave us particular views of the characters played. We thought Hywel Bennett as Leonard sounded older and more confident than in the TV version – as indeed did Romaine. This meant that the TV version’s revelation of Leonard and Romaine’s crimes, and the level of manipulation employed, were perhaps more surprising.

We also noted how the revelation of Romaine’s performance as Mrs Mogdon occurred in different ways: in the short story Mayherne realises it due to Romaine and the part she plays sharing the same ‘foreign gesture’. Since radio has the audio advantage, it chooses to damn Romaine by her own words: ‘a tree is a tree is a tree’. She utters this both while playing Mrs Mogdon and in court giving evidence. Since the TV version affords Mayhew a larger place in the narrative, and also significantly differs in its characterisation of Romaine, it is framed as something Mayhew finds out only after his success in the defence of Leonard leads to him taking a holiday in Le Touquet. Seeing Leonard and his new bride outside a hotel, Mayhew pays them a visit: Romaine calmly tells him what they had done. This underlined the less calculating Romaine in the radio adaptation as the warmth of her voice and her talk of love contrasts to the TV Romaine’s coldness and the impression she is more intent on survival. In Wilder’s 1957 film Marlene Dietrich as ‘Christine’ re-enacts her earlier performance as the scarred woman for the barrister Sir Wilfrid Robarts, played by Charles Laughton. While Christine seems to revel in her talent, Andrea Riseborough in the TV adaptation is more subdued and matter-of-fact.

adaptation as the warmth of her voice and her talk of love contrasts to the TV Romaine’s coldness and the impression she is more intent on survival. In Wilder’s 1957 film Marlene Dietrich as ‘Christine’ re-enacts her earlier performance as the scarred woman for the barrister Sir Wilfrid Robarts, played by Charles Laughton. While Christine seems to revel in her talent, Andrea Riseborough in the TV adaptation is more subdued and matter-of-fact.

Another significant difference between the original and its several adaptations are whether characters get their comeuppance. While the short story and radio version end with the revelation of the deception, and the impression no justice will be served, the film and TV versions tackle the matter in alternative ways. In the film, Leonard and Christine do not ‘get away with it’ since the existence of Leonard’s girlfriend is revealed in the court room and Christine takes her revenge by stabbing him. It was mentioned that the filming of this is especially instructive as the light from Sir Wilfrid’s monocle, which he spins on the desk, highlights the presence of the knife. In effect, this means that Sir Wilfrid, by now fully cognizant of Leonard’s crime and Christine’s lies, somehow directs Christine towards committing her crime.

In the TV version Leonard and Romaine do appear to have escaped justice – instead Janet McKenzie is wrongly convicted and hanged for their crime. Furthermore, Mayhew was instrumental in Janet’s arrest, causing him much distress when the truth is revealed by Leonard and Romaine. Mayhew is unable to bear the guilt and walks into the sea at the end. Some in the group did not like the fact that Mayhew is the only one to fully accept his guilt for his actions, this seeming to let Leonard and Romaine off the hook. However a note of caution is also sounded for the ‘happy’ couple: Leonard asks whether Romaine will need him much longer, to which she replies that she will – as long as he’s not boring. In addition to suggesting Leonard may yet be punished for him crime, this gives further insight into Leonard and Romaine’s relationship as it shows her very much in control.

We spoke further on the matter of gender and especially Romaine. We commented on her emotionless rendering of her signature tune ‘Let me Call You Sweetheart’ at the theatre throughout the TV adaptation. Although her skimpy costume and centre stage placement suggest objectification, she is in fact very closed. This was also true of her seeming breakdown in court: she is confronted by the letters to her non-existent lover she has in fact planted in order to keep her husband out of prison. Although she performs anger at having been discovered, allowing those who accuse her to feel especially smug in the face of her abjectness, she is in fact more opaque than ever – and a willing victim, sacrificing herself for a higher purpose. She is one of the few women who actually get to speak in court and have their words believed – even though ironically they are not the truth. Janet’s evidence is (accurately) put down to having

We spoke further on the matter of gender and especially Romaine. We commented on her emotionless rendering of her signature tune ‘Let me Call You Sweetheart’ at the theatre throughout the TV adaptation. Although her skimpy costume and centre stage placement suggest objectification, she is in fact very closed. This was also true of her seeming breakdown in court: she is confronted by the letters to her non-existent lover she has in fact planted in order to keep her husband out of prison. Although she performs anger at having been discovered, allowing those who accuse her to feel especially smug in the face of her abjectness, she is in fact more opaque than ever – and a willing victim, sacrificing herself for a higher purpose. She is one of the few women who actually get to speak in court and have their words believed – even though ironically they are not the truth. Janet’s evidence is (accurately) put down to having been coached by the prosecution team. We compared Romaine’s largely subdued character to a similar quality in Mayhew’s wife (a newly invented character for the TV adaption). The very presence of Mrs Mayhew increased the number of women playing an important part in the narrative, and showed one side of sexual politics as she endured her husband’s attentions.

been coached by the prosecution team. We compared Romaine’s largely subdued character to a similar quality in Mayhew’s wife (a newly invented character for the TV adaption). The very presence of Mrs Mayhew increased the number of women playing an important part in the narrative, and showed one side of sexual politics as she endured her husband’s attentions.

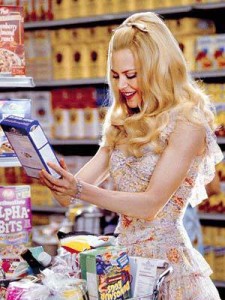

Unsurprisingly, the TV version was also more modern in its approach to sexual politics. Emily’s maid Janet appears to have a passion for her employer, the cougar-ish Emily, played by Kim Catrall. Emily was not just stunningly attractive, but open about her desire for Leonard. Despite the more modern production context, this made the force used in killing her seem more like a punishment; this was especially evident when we re-watched the scenes in which Emily and Leonard first met and she invited him back to her house. Rather than Leonard helping a little old lady who’d dropped her parcels in the street, it is Leonard who is clumsy as the tray of drinks he is carrying at his place of work crashes to the ground. The fact that this happens just after Emily has passed him on the stairs seems to afford her a certain power of the gaze (heightened later as she watches him in the bath, objectifying his body and feeding him scraps of food from a plate as though he were a pet). Leonard is shown to be her prey, unable to escape her attentions.

Unsurprisingly, the TV version was also more modern in its approach to sexual politics. Emily’s maid Janet appears to have a passion for her employer, the cougar-ish Emily, played by Kim Catrall. Emily was not just stunningly attractive, but open about her desire for Leonard. Despite the more modern production context, this made the force used in killing her seem more like a punishment; this was especially evident when we re-watched the scenes in which Emily and Leonard first met and she invited him back to her house. Rather than Leonard helping a little old lady who’d dropped her parcels in the street, it is Leonard who is clumsy as the tray of drinks he is carrying at his place of work crashes to the ground. The fact that this happens just after Emily has passed him on the stairs seems to afford her a certain power of the gaze (heightened later as she watches him in the bath, objectifying his body and feeding him scraps of food from a plate as though he were a pet). Leonard is shown to be her prey, unable to escape her attentions.

That Leonard was unable to escape Emily is also seen in the dynamic between him, Janet and Emily. At the beginning, Leonard is clearly marked as having less agency than Janet. Janet directly tells him to leave within seconds of first meeting him. Emily’s desire, however, trumps her employee’s reservations, with Leonard becoming increasingly forthright (even vindictive) with Janet, and taking advantage of his opportunity. In the end this means that it is Emily and Janet who are punished – both for their desires. Leonard takes Emily’s life in a particularly savage and bloody way, and the fact Janet is wrongly executed for murdering her beloved mistress makes her punishment especially cruel.

That Leonard was unable to escape Emily is also seen in the dynamic between him, Janet and Emily. At the beginning, Leonard is clearly marked as having less agency than Janet. Janet directly tells him to leave within seconds of first meeting him. Emily’s desire, however, trumps her employee’s reservations, with Leonard becoming increasingly forthright (even vindictive) with Janet, and taking advantage of his opportunity. In the end this means that it is Emily and Janet who are punished – both for their desires. Leonard takes Emily’s life in a particularly savage and bloody way, and the fact Janet is wrongly executed for murdering her beloved mistress makes her punishment especially cruel.

While in the cases of Janet and Emily the punishment meted out in linked to gender, the matter of Class comes in to play in different versions. In the film, Sir Wilfrid is higher class and, as noted above, can be seen to have directed justice for his own ends. By contrast, Mayhew in the TV version is clearly shown to be middle class- he has a

While in the cases of Janet and Emily the punishment meted out in linked to gender, the matter of Class comes in to play in different versions. In the film, Sir Wilfrid is higher class and, as noted above, can be seen to have directed justice for his own ends. By contrast, Mayhew in the TV version is clearly shown to be middle class- he has a comfortable home; but occupies a dank and leaky office and has to bribe police officers for access to potential cases. His punishment comes due to his own error, made partly due to his grief over the loss of his son, killed when Mayhew lied about his son’s age so that they could go to war together. Leonard is clearly a surrogate son he is determined to save.

comfortable home; but occupies a dank and leaky office and has to bribe police officers for access to potential cases. His punishment comes due to his own error, made partly due to his grief over the loss of his son, killed when Mayhew lied about his son’s age so that they could go to war together. Leonard is clearly a surrogate son he is determined to save.

The TV version’s post World War I setting was especially important. This tied Leonard and Romaine closer together in their desperation – including their first meeting at the very start of the adaptation. We noted that this scene could be interpreted in several ways: as a fairly direct telling of a soldier and a young woman (possibly a prisoner, kept near the front to service the soldiers) meeting, a dream of either Leonard or Romaine, or a metaphorical representation of their relationship to each other and the world.

We further pondered the decision to set the adaptation just post World War I. While Christie’s short story was published in 1933, there was little mention of the conflict of twenty years earlier. The radio adaptation, by contrast, chose to place the action post-World War II. We commented on the fact that adapter Sarah Phelps had also created and written the 6 part BBC drama series The Crimson Field. Taking place during World War I, this focused on strong women working as nurses near the front. The post-World War I setting also seems especially timely given the continuing centenary commemorations today. We thought it gave more cause (if not justification) to the characters of Leonard and Romaine. They attempt to excuse themselves to Mayhew by arguing that the murder of Emily is just one more death – what is to be expected when we put the young through the horrifying experience of fighting a war. In relation to Romaine, we additionally considered that a post-World War II setting might unnecessarily complicate her Austrian heritage, and hammer home too forcefully any suggestion of Nazism in Phelps’ expanded narrative.

We further pondered the decision to set the adaptation just post World War I. While Christie’s short story was published in 1933, there was little mention of the conflict of twenty years earlier. The radio adaptation, by contrast, chose to place the action post-World War II. We commented on the fact that adapter Sarah Phelps had also created and written the 6 part BBC drama series The Crimson Field. Taking place during World War I, this focused on strong women working as nurses near the front. The post-World War I setting also seems especially timely given the continuing centenary commemorations today. We thought it gave more cause (if not justification) to the characters of Leonard and Romaine. They attempt to excuse themselves to Mayhew by arguing that the murder of Emily is just one more death – what is to be expected when we put the young through the horrifying experience of fighting a war. In relation to Romaine, we additionally considered that a post-World War II setting might unnecessarily complicate her Austrian heritage, and hammer home too forcefully any suggestion of Nazism in Phelps’ expanded narrative.

The legacy of World War I is also seen in the relationship of the Mayhews. Indeed it underpins Mayhew’s relationship with Leonard and Romaine. The former is the surrogate for the son lost at war, and his sympathy for the latter initially comes from a sentimentalised romantic desire which is not reciprocated at home: his wife blames him for their son’s death. Significantly while experiences during the War have desensitised Leonard and Romaine, Mayhew is still capable of wanting love, and of feeling guilt. It was also mentioned that in the introduction to the BBC’s new tie-in version of the short story, Phelps highlighted the matter of characters performing – which we specially connected to the female characters. This adds another level when considering the performative nature of the mediums of TV, film and radio.

In more general terms we also commented on the pacing of the TV production and its cinematography. Extending to two hours, even allowing for the extra twist Phelps had added of Mayhew ‘discovering’ Janet’s guilt as the Mayhews holidayed in Le Touquet, was a stretch. This is hardly surprising when we note that Phelps’ 2015 3 part TV adaptation of Christie’s novel And Then There Were None had far more characters, and murders, to dramatize. While the revelation that Romaine was going to be a witness for the prosecution rather than the defence acted as a useful pivot between episodes 1 and 2, some of the scenes and shots seemed overlong. We wondered if sometimes the shots lasted so long to allow us to try and discern what was happening in the murkier scenes. (There was a pervading yellowy green atmosphere to some of the scenes of Mayhew in London – perhaps an ongoing reminder of the mustard gas poisoning he is suffering from.) Extended shots and scenes on occasion hammered home aspects a little too forcefully, with the images of Emily’s hitherto gleamingly white cat padding in her recently murdered mistress’s blood especially gratuitous.

In more general terms we also commented on the pacing of the TV production and its cinematography. Extending to two hours, even allowing for the extra twist Phelps had added of Mayhew ‘discovering’ Janet’s guilt as the Mayhews holidayed in Le Touquet, was a stretch. This is hardly surprising when we note that Phelps’ 2015 3 part TV adaptation of Christie’s novel And Then There Were None had far more characters, and murders, to dramatize. While the revelation that Romaine was going to be a witness for the prosecution rather than the defence acted as a useful pivot between episodes 1 and 2, some of the scenes and shots seemed overlong. We wondered if sometimes the shots lasted so long to allow us to try and discern what was happening in the murkier scenes. (There was a pervading yellowy green atmosphere to some of the scenes of Mayhew in London – perhaps an ongoing reminder of the mustard gas poisoning he is suffering from.) Extended shots and scenes on occasion hammered home aspects a little too forcefully, with the images of Emily’s hitherto gleamingly white cat padding in her recently murdered mistress’s blood especially gratuitous.

As ever, do log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.