Discussion on Libel included: its melodramatic elements in terms of its main narrative line of imposture, the villain/victim dynamic, coincidence, the courtroom setting and the rhythm of the plot which contains multiple flashbacks, especially emotional moments, and the film’s use of music; the matter of trauma caused by war and the attempted recovery of repressed memory; doubling in the source text and adaptations; doubling in films; the doubling of Mark and Frank – both played by Dirk Bogarde; narcissism and homosexual desire; how the fact Bogarde plays both posh Mark and lower-class Frank related to his screen and star images; scandal magazines.

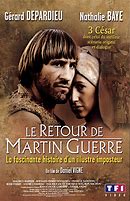

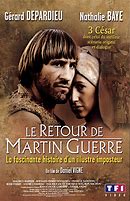

Our discussion began with comments on films which had similar narratives. The plot where a man commits, or is accused of committing, identity theft recalled The Captive Heart (1946, Basil Dearden). In this, Michael Redgrave starred as a Czechoslovakian prisoner of war posing as (Redgrave’s real-life wife) Rachel Kempson’s RAF husband through letters to her. We also spoke about the French film The Return of Martin Guerre (1982, France, Daniel Vigne), with Gerard Depardieu as the titular character and Nathalie Baye as Bertrande, his wife. Although this was based on a historical case from 16th century France, Hollywood later updated and relocated it to Civil War America in Somersby (1993, Jon Amiel) starring Richard Gere and Jodie Foster.

Our discussion began with comments on films which had similar narratives. The plot where a man commits, or is accused of committing, identity theft recalled The Captive Heart (1946, Basil Dearden). In this, Michael Redgrave starred as a Czechoslovakian prisoner of war posing as (Redgrave’s real-life wife) Rachel Kempson’s RAF husband through letters to her. We also spoke about the French film The Return of Martin Guerre (1982, France, Daniel Vigne), with Gerard Depardieu as the titular character and Nathalie Baye as Bertrande, his wife. Although this was based on a historical case from 16th century France, Hollywood later updated and relocated it to Civil War America in Somersby (1993, Jon Amiel) starring Richard Gere and Jodie Foster.

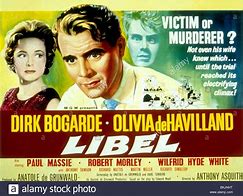

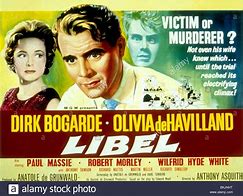

In addition to Libel’s central melodramatic plot-line, which not only needs the audience to suspend its disbelief to some degree but also promises a revelation of the truth, we considered whether the film employed stock characters thought to be typical to melodrama. Because of the confusion over the main character’s identity, the matter was very blurred. This is well illustrated by a contemporary poster for the film which poses the question of whether Baronet Mark Loddon (Dirk Bogarde) is ‘Victim or Murderer?’ Furthermore, the next line, ‘not even his wife knew which’ points to Margaret Loddon (Olivia de Havilland) as the real victim if ‘Mark’ is in fact ‘Frank’ playing a role. The matter turns out to be even more nuanced when ‘Number 15’ (a severely injured man, and like Mark and Frank also played by Bogarde, and therefore either the ‘real’ Mark or the ‘real’ Frank) appears in court. Towards the end of the film the recovery of Mark’s previously repressed memory further complicates any view of him being wholly ‘good’ or ‘bad’.

In addition to Libel’s central melodramatic plot-line, which not only needs the audience to suspend its disbelief to some degree but also promises a revelation of the truth, we considered whether the film employed stock characters thought to be typical to melodrama. Because of the confusion over the main character’s identity, the matter was very blurred. This is well illustrated by a contemporary poster for the film which poses the question of whether Baronet Mark Loddon (Dirk Bogarde) is ‘Victim or Murderer?’ Furthermore, the next line, ‘not even his wife knew which’ points to Margaret Loddon (Olivia de Havilland) as the real victim if ‘Mark’ is in fact ‘Frank’ playing a role. The matter turns out to be even more nuanced when ‘Number 15’ (a severely injured man, and like Mark and Frank also played by Bogarde, and therefore either the ‘real’ Mark or the ‘real’ Frank) appears in court. Towards the end of the film the recovery of Mark’s previously repressed memory further complicates any view of him being wholly ‘good’ or ‘bad’.

The film’s many melodramatic twists on turns depended to a large extent on coincidences. The central one – that of two men who look nearly exactly alike (both are played by Dirk Bogarde, after all) apart from hair colour and the matter of a few missing fingers – being interned in the same prisoner of war camp – took a fair suspension of disbelief on the audience’s part. Some of the explanations for the physical changes which have occurred to the present-day (and possibly ‘fake’) Mark also stretched credence, especially since they made him resemble Frank. The turning of Mark’s hair from dark to silver (like Frank’s) could be explained by age and the trauma of war. (It was in any case helpful for distinguishing between the dark-haired Mark and the silver-haired Frank in the flashbacks.) However, the chance that Mark lost fingers during his escape which exactly matched Frank’s disability seemed slim.

The film’s many melodramatic twists on turns depended to a large extent on coincidences. The central one – that of two men who look nearly exactly alike (both are played by Dirk Bogarde, after all) apart from hair colour and the matter of a few missing fingers – being interned in the same prisoner of war camp – took a fair suspension of disbelief on the audience’s part. Some of the explanations for the physical changes which have occurred to the present-day (and possibly ‘fake’) Mark also stretched credence, especially since they made him resemble Frank. The turning of Mark’s hair from dark to silver (like Frank’s) could be explained by age and the trauma of war. (It was in any case helpful for distinguishing between the dark-haired Mark and the silver-haired Frank in the flashbacks.) However, the chance that Mark lost fingers during his escape which exactly matched Frank’s disability seemed slim.

Coincidence also led to the Canadian Jeffrey Buckenham (Paul Massie) seeing the live television broadcast of the present-day Mark showing Richard Dimbleby around his stately home. Buckenham states that he is only in the UK for a couple of days. His presence in a pub which happens to boast a television which is tuned into the correct channel at just the right time (especially since in the 1950s television programmes often aired just once) is, however, superseded by another coincidence. The other pub customers object to viewing the programme, and Buckenham persuades fellow customer Maisie (Millicent Martin), whom he has only just met, to let him view her television in her nearby flat. The choice of the TV medium almost seems to deliberately underline the unlikeliness of the situation. Buckenham could have been exposed to photographs of Mark in a newspaper or a newsreel, which would have relied less on the precise timing of Buckenham’s reception. Furthermore, it is in an incredible twist of fate that Buckenham is the only person to have known both Mark and Frank well – the three escaped the prisoner of war camp together.

Coincidence also led to the Canadian Jeffrey Buckenham (Paul Massie) seeing the live television broadcast of the present-day Mark showing Richard Dimbleby around his stately home. Buckenham states that he is only in the UK for a couple of days. His presence in a pub which happens to boast a television which is tuned into the correct channel at just the right time (especially since in the 1950s television programmes often aired just once) is, however, superseded by another coincidence. The other pub customers object to viewing the programme, and Buckenham persuades fellow customer Maisie (Millicent Martin), whom he has only just met, to let him view her television in her nearby flat. The choice of the TV medium almost seems to deliberately underline the unlikeliness of the situation. Buckenham could have been exposed to photographs of Mark in a newspaper or a newsreel, which would have relied less on the precise timing of Buckenham’s reception. Furthermore, it is in an incredible twist of fate that Buckenham is the only person to have known both Mark and Frank well – the three escaped the prisoner of war camp together.

More believable were aspects which weighed for the likelihood of the present-day Mark being an imposter. Frank’s profession as a ‘provincial actor’, meaning that he could conceivably imitate Mark’s voice and gestures. The flashbacks show this convincingly since Buckenham remarks that he could ‘understudy’ the ‘star’ part of Mark Loddon. The prisoner of war scenes also reveal that Frank was present while Mark described some of his past, and his fiancée. Frank could therefore make use of such information.

We pondered the flashbacks a little more. While some of these recounted the same events, such as the misdelivering of one of Mark’s letters to Frank, the details differed depending on who was giving evidence. Buckenham’s included more of an emphasis on Frank’s violence. They are not necessarily contradictory, however, unlike the lying flashback in Alfred Hitchcock’s Stage Fright (1950) for example). In this film they add further nuance, and indeed more evidence for Buckenham’s claims Mark is an imposter.

We pondered the flashbacks a little more. While some of these recounted the same events, such as the misdelivering of one of Mark’s letters to Frank, the details differed depending on who was giving evidence. Buckenham’s included more of an emphasis on Frank’s violence. They are not necessarily contradictory, however, unlike the lying flashback in Alfred Hitchcock’s Stage Fright (1950) for example). In this film they add further nuance, and indeed more evidence for Buckenham’s claims Mark is an imposter.

We also discussed how coincidence played a part in action which occurred prior to the film. The fact that Mark was engaged, but not yet married, was significant. It meant that the chance of an imposter being able to fool his family, and specifically his fiancée, was more likely. This was aided by the present-day Mark’s amnesia which helpfully provides an excuse for why he cannot remember certain details of what happened before the war.

Two important courtroom revelations also relied on coincidence. A physically and, more importantly, severely mentally damaged man – known only as Number 15 – is produced in the court by the defence team. Recognisably played by Bogarde, this means that somehow Frank (or Mark!) survived the injuries sustained abroad and has at last been identified. The final coincidence which in fact clinches the fact of Mark’s innocence also occurs in the court room. He has finally remembered the medallion charm his fiancée gave to him, and more significantly recalls that it is hidden in the coat Number 15 was found wearing. Conveniently this coat has been kept, and indeed is present in court.

Two important courtroom revelations also relied on coincidence. A physically and, more importantly, severely mentally damaged man – known only as Number 15 – is produced in the court by the defence team. Recognisably played by Bogarde, this means that somehow Frank (or Mark!) survived the injuries sustained abroad and has at last been identified. The final coincidence which in fact clinches the fact of Mark’s innocence also occurs in the court room. He has finally remembered the medallion charm his fiancée gave to him, and more significantly recalls that it is hidden in the coat Number 15 was found wearing. Conveniently this coat has been kept, and indeed is present in court.

The fact that much of the film’s action, and the framing of flashbacks, take place in court, is significant. In this formal setting, elderly, privileged, white men in traditional robes follow procedures which have been established for centuries. Its staid atmosphere contrasts to the action in the flashbacks and the intensity of the revelations which are divulged, providing a rhythm of lows and highs. Even the brilliant British actors Robert Morley, Wilfrid Hyde-White and Richard Wattis, who are not exactly underplaying their roles as legal stalwarts, seem surprised by the level of revelation. This was also reflected by the audible gasps of those in the public gallery, which were in turn echoed by members of the melodrama research group!

The fact that much of the film’s action, and the framing of flashbacks, take place in court, is significant. In this formal setting, elderly, privileged, white men in traditional robes follow procedures which have been established for centuries. Its staid atmosphere contrasts to the action in the flashbacks and the intensity of the revelations which are divulged, providing a rhythm of lows and highs. Even the brilliant British actors Robert Morley, Wilfrid Hyde-White and Richard Wattis, who are not exactly underplaying their roles as legal stalwarts, seem surprised by the level of revelation. This was also reflected by the audible gasps of those in the public gallery, which were in turn echoed by members of the melodrama research group!

We also paid attention to moments when characters displayed extreme emotion. Mark’s struggling with his memory, and his being seemingly haunted by his own reflection, led to outbursts both at home and in court. His wife is more emotionally stable, providing Mark with solid support. But after she has denounced him in court as a fraud, the enormity of his presumed deception distresses her and she verbally attacks Mark. Following this, she leans against the hotel door, exhausted, and calls out his name.

Much of this emotion is underscored by the film’s music. We especially noted the use of a particular refrain – the whistling of the English folk song ‘Early One Morning’ – in the narrative. As well as further suggesting that Mark is an imposter (we see Frank whistling the tune in the flashbacks and it is part of what makes Buckenham suspicious of him) the lyrics of the chorus seem to reinforce Mark’s wife’s view that she has been lied to:

Oh, don’t deceive me,

Oh, never leave me,

How could you use

A poor maiden so?

The theme of deception works on several levels in the film, including that of self-deception. Mark claims to have lost his memory due to the trauma of war. While some in the film think that this is a convenient way for Frank to explain any gaps in his knowledge of a life he has after all not lived, it turns out to in fact be the case. He is in fact the real Mark, though is unaware of who he is for most of the film. A flashback reveals the memory Mark has repressed. He is shown to viciously attack Frank after Frank decided to put Buckenham’s suggestion of taking over the ‘star’ part into practice. This explains his distress when seeing his own reflection in a mirror – it is a reminder of the man with his face who turned against him. It is also significantly suggestive of a fear of himself. Though Mark acts in self-defence, his sustained attack is unjustifiable. The effects of his actions are seen as Number 15 shuffles into court, physically but even more overwhelmingly mentally and emotionally damaged. This speaks to a more universal fear of what the self is capable of.

The recovery of repressed memory reminded us of when the melodrama research group screened The Awakening (2011, Nick Murphy). The Awakening is especially tied to time and place as the film’s protagonist, Florence (Rebecca Hall), unknowingly returns to her childhood home after the first world war in order for her to remember her past. (You can see a summary of the group’s previous discussion here: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2014/03/01/summary-of-discussion-on-the-awakening/).

The recovery of repressed memory reminded us of when the melodrama research group screened The Awakening (2011, Nick Murphy). The Awakening is especially tied to time and place as the film’s protagonist, Florence (Rebecca Hall), unknowingly returns to her childhood home after the first world war in order for her to remember her past. (You can see a summary of the group’s previous discussion here: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2014/03/01/summary-of-discussion-on-the-awakening/).

A film which had more direct comparisons to Libel, and indeed was released more than a decade previously, is Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945). Like Mark, the character Gregory Peck plays – Dr Anthony Edwardes – is thought to be an imposter. He is suspected by Dr Constance Petersen (Ingrid Bergman), who nonetheless does not believe his admission that he has killed the real Dr Edwardes. While in fact he is not who he claims to be, Peck’s character, like Mark, is suffering from amnesia. Because of the profession Dr Petersen and Dr Edwardes share (they are psychoanalysts) this aspect is especially well-worked through. It is explained that he is suffering from a guilt complex. He was present there when the real Dr Edwardes accidentally fell to his death, which recalled a childhood accident in which his brother died.

A film which had more direct comparisons to Libel, and indeed was released more than a decade previously, is Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945). Like Mark, the character Gregory Peck plays – Dr Anthony Edwardes – is thought to be an imposter. He is suspected by Dr Constance Petersen (Ingrid Bergman), who nonetheless does not believe his admission that he has killed the real Dr Edwardes. While in fact he is not who he claims to be, Peck’s character, like Mark, is suffering from amnesia. Because of the profession Dr Petersen and Dr Edwardes share (they are psychoanalysts) this aspect is especially well-worked through. It is explained that he is suffering from a guilt complex. He was present there when the real Dr Edwardes accidentally fell to his death, which recalled a childhood accident in which his brother died.

We also especially focused on the relation of the doubling not just to the self, and to psychology, but to the medium of film. In relation to this, it is worth contemplating the original source text and other adaptations. Edward Wooll’s play, on which the film was based, was first staged in 1934. The 1930-1939 volume of J.P. Wearing’s incredibly helpful The London Stage: A Calendar of Productions, Performers, and Personnel (1990) contains the cast list and this suggests that the character of Frank does not appear in the original production. This is unsurprising, since the doubling would be extremely difficult to achieve on stage. It is however, possible that it took place in the novelised version Wooll wrote in 1935.

We also especially focused on the relation of the doubling not just to the self, and to psychology, but to the medium of film. In relation to this, it is worth contemplating the original source text and other adaptations. Edward Wooll’s play, on which the film was based, was first staged in 1934. The 1930-1939 volume of J.P. Wearing’s incredibly helpful The London Stage: A Calendar of Productions, Performers, and Personnel (1990) contains the cast list and this suggests that the character of Frank does not appear in the original production. This is unsurprising, since the doubling would be extremely difficult to achieve on stage. It is however, possible that it took place in the novelised version Wooll wrote in 1935.

Several radio and television versions were made between 1934 and the 1970s. According to my research on the internet movie database (https://www.imdb.com/) and the BBC’s excellent genome project (https://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk/), which gives access to all the BBC’s radio and TV listings from 1923 to 2009, these productions also do not include Frank. Doubling would have been possible on radio, but certainly more impactful on screen. The fact that much TV of the time was shown live or ‘as live’ making manipulation of the image difficult, or indeed consisted of excerpts of stage plays, perhaps partially explains why the doubling remains a peculiarly cinematic phenomenon.

Several radio and television versions were made between 1934 and the 1970s. According to my research on the internet movie database (https://www.imdb.com/) and the BBC’s excellent genome project (https://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk/), which gives access to all the BBC’s radio and TV listings from 1923 to 2009, these productions also do not include Frank. Doubling would have been possible on radio, but certainly more impactful on screen. The fact that much TV of the time was shown live or ‘as live’ making manipulation of the image difficult, or indeed consisted of excerpts of stage plays, perhaps partially explains why the doubling remains a peculiarly cinematic phenomenon.

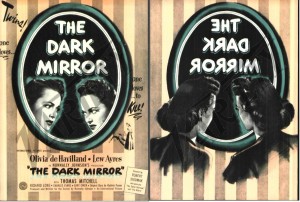

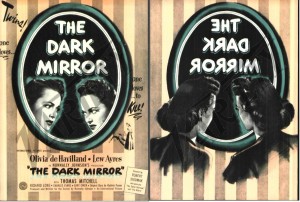

Such a view is supported when we consider that other instances of doubling are especially linked to film. We’ve viewed and discussed some examples in the melodrama research group. In addition to instances of doubling which are related to the split self (The Student of Prague (1913, Stella Rye), Black Swan (2010, Darren Aronofsky), The Double (2013, Richard Ayoade)) we’ve also seen stars playing dual roles: Mary Pickford in Stella Maris (1918, Marshall Neilan) and Norma Shearer in Lady of the Night (1925, Monta Bell). You can also see summaries of our discussion on Olivia de Havilland playing twins in The Dark Mirror (1946, Robert Siodmak) here: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2015/01/31/summary-of-discussion-on-the-dark-mirror/. Jeremy Irons also undertook such a feat in Dead Ringers (1988, David Cronenberg), a summary of our discussion appearing here: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2015/03/26/summary-of-discussion-on-dead-ringers/.

Such a view is supported when we consider that other instances of doubling are especially linked to film. We’ve viewed and discussed some examples in the melodrama research group. In addition to instances of doubling which are related to the split self (The Student of Prague (1913, Stella Rye), Black Swan (2010, Darren Aronofsky), The Double (2013, Richard Ayoade)) we’ve also seen stars playing dual roles: Mary Pickford in Stella Maris (1918, Marshall Neilan) and Norma Shearer in Lady of the Night (1925, Monta Bell). You can also see summaries of our discussion on Olivia de Havilland playing twins in The Dark Mirror (1946, Robert Siodmak) here: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2015/01/31/summary-of-discussion-on-the-dark-mirror/. Jeremy Irons also undertook such a feat in Dead Ringers (1988, David Cronenberg), a summary of our discussion appearing here: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2015/03/26/summary-of-discussion-on-dead-ringers/.

Not only is the film audience afforded the opportunity of seeing both Mark and Frank, importantly these characters are able to see one another. There was an undercurrent of narcissism present in the relationship between the two men. Frank admired Mark so much as his ego ideal (the self he wanted to be) that he tried to take Mark’s life – both literally and figuratively. In addition, there was the suggestion of homosexual desire. Buckenham’s defending counsel, Hubert Foxley (Hyde-White) states that Mark has kept many things from his wife. While ostensibly this refers to the accusation that Mark has stolen another man’s identity, we might also consider that this refers to other parts of his private life. Such a reading seems especially indicated by the tone of Foxley’s probing. He asks what happened between the two men when they were left alone on one occasion at the prisoner of war camp, repeating ‘and then….?’ in such a way as to imply that more has occurred.

Not only is the film audience afforded the opportunity of seeing both Mark and Frank, importantly these characters are able to see one another. There was an undercurrent of narcissism present in the relationship between the two men. Frank admired Mark so much as his ego ideal (the self he wanted to be) that he tried to take Mark’s life – both literally and figuratively. In addition, there was the suggestion of homosexual desire. Buckenham’s defending counsel, Hubert Foxley (Hyde-White) states that Mark has kept many things from his wife. While ostensibly this refers to the accusation that Mark has stolen another man’s identity, we might also consider that this refers to other parts of his private life. Such a reading seems especially indicated by the tone of Foxley’s probing. He asks what happened between the two men when they were left alone on one occasion at the prisoner of war camp, repeating ‘and then….?’ in such a way as to imply that more has occurred.

We can connect such readings more closely to the fact that Mark and Frank were played by Bogarde. Our view of a star’s screen image is of course informed by the other roles he or she plays, including in terms of character and class, as well as any knowledge we have of a star’s ‘real’ self (star image). We noted how in Esther Waters Bogarde played a gambler of the lower classes, and while he is the cause of the heroine’s downfall his character is nuanced. Bogarde’s ability to play two extremes was seen to even greater effect in Hunted as a murderer on the run who nonetheless cares for a neglected little boy. In the seven years between Hunted and Libel, Bogarde appeared in a variety of films, and began to be listed by the trade magazine Motion Picture Herald as a draw at the British box office.

We can connect such readings more closely to the fact that Mark and Frank were played by Bogarde. Our view of a star’s screen image is of course informed by the other roles he or she plays, including in terms of character and class, as well as any knowledge we have of a star’s ‘real’ self (star image). We noted how in Esther Waters Bogarde played a gambler of the lower classes, and while he is the cause of the heroine’s downfall his character is nuanced. Bogarde’s ability to play two extremes was seen to even greater effect in Hunted as a murderer on the run who nonetheless cares for a neglected little boy. In the seven years between Hunted and Libel, Bogarde appeared in a variety of films, and began to be listed by the trade magazine Motion Picture Herald as a draw at the British box office.

Soon after Hunted, Bogarde played another man-on-the-run, though this time an innocent one, in Desperate Moment (1953, Compton Bennett). Other roles saw Bogarde breaking the law. In The Gentle Gunman (1952, Basil Dearden) he was a member of the IRA and in The Sleeping Tiger (1954, Joseph Losey) a man who hold a psychiatrist at gunpoint. In Cast a Dark Shadow (1955, Lewis Gilbert) Bogarde’s repulsive wife-killer is specifically coded as a member of the lower classes (despite having married into wealth). Similarly, the feckless and petty thief he portrays in Anthony Asquith’s 1958 adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s play The Doctor’s Dilemma is poor. Bogarde also played non-criminal types, in both light comedies (most notably in 3 of the Doctor series of films– 1954, 1955 and 1957 – and action or adventure narratives like Campbell’s Kingdom (1957), all directed by Ralph Thomas. Thomas was also at the helm when Bogarde starred as Sydney Carton in an adaptation of Charles Dickens’ 1859 novel A Tale of Two Cities and in the war picture The Wind Cannot Read (both 1958). Like other stars of the time, Bogarde appeared in several war

Soon after Hunted, Bogarde played another man-on-the-run, though this time an innocent one, in Desperate Moment (1953, Compton Bennett). Other roles saw Bogarde breaking the law. In The Gentle Gunman (1952, Basil Dearden) he was a member of the IRA and in The Sleeping Tiger (1954, Joseph Losey) a man who hold a psychiatrist at gunpoint. In Cast a Dark Shadow (1955, Lewis Gilbert) Bogarde’s repulsive wife-killer is specifically coded as a member of the lower classes (despite having married into wealth). Similarly, the feckless and petty thief he portrays in Anthony Asquith’s 1958 adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s play The Doctor’s Dilemma is poor. Bogarde also played non-criminal types, in both light comedies (most notably in 3 of the Doctor series of films– 1954, 1955 and 1957 – and action or adventure narratives like Campbell’s Kingdom (1957), all directed by Ralph Thomas. Thomas was also at the helm when Bogarde starred as Sydney Carton in an adaptation of Charles Dickens’ 1859 novel A Tale of Two Cities and in the war picture The Wind Cannot Read (both 1958). Like other stars of the time, Bogarde appeared in several war  films in the 1950s, beginning with Appointment in London (Philip Leacock) in 1953. In these films Bogarde mostly played members of the middle or the upper classes. His status as a star at the British box office at this time was impressive, 5th in both 1953 and 1959, and in between rose higher: 2nd (1954), 1st (1955), 3rd (1956), 1st (1957) and 2nd (1958).

films in the 1950s, beginning with Appointment in London (Philip Leacock) in 1953. In these films Bogarde mostly played members of the middle or the upper classes. His status as a star at the British box office at this time was impressive, 5th in both 1953 and 1959, and in between rose higher: 2nd (1954), 1st (1955), 3rd (1956), 1st (1957) and 2nd (1958).

Bogarde’s appearance as Sydney Carton in A Tale of Two Cities is particularly worth singling out in comparison to Libel. The narrative turns on the uncanny physical similarity between drunken English lawyer Carton and French aristocrat Charles Darnay. Carton famously nobly sacrifices his own life for Darnay’s, substituting himself for the Frenchman at the guillotine. While Bogarde does not play both parts in the film (Paul Guers is Darnay), this has occasionally been the case. William Farnum starred in both roles in Frank Lloyd’s 1917 silent film and Desmond Llewelyn in a 1952 television adaptation. The two 1980 TV versions also used this device – Paul Shelley appearing as Carton and Darnay in the mini-series and Charles Sarandon doing so in the TV movie. Libel therefore addresses the matter of the double more directly. It also problematizes the matter due to the fact neither the audience, nor Mark, is sure of Mark’s identity.

Bogarde’s appearance as Sydney Carton in A Tale of Two Cities is particularly worth singling out in comparison to Libel. The narrative turns on the uncanny physical similarity between drunken English lawyer Carton and French aristocrat Charles Darnay. Carton famously nobly sacrifices his own life for Darnay’s, substituting himself for the Frenchman at the guillotine. While Bogarde does not play both parts in the film (Paul Guers is Darnay), this has occasionally been the case. William Farnum starred in both roles in Frank Lloyd’s 1917 silent film and Desmond Llewelyn in a 1952 television adaptation. The two 1980 TV versions also used this device – Paul Shelley appearing as Carton and Darnay in the mini-series and Charles Sarandon doing so in the TV movie. Libel therefore addresses the matter of the double more directly. It also problematizes the matter due to the fact neither the audience, nor Mark, is sure of Mark’s identity.

Libel also adds aspects which connect more specifically to Bogarde’s star image. John Style’s chapter “Dirk Bogarde’s Sidney Carton—More Faithful to the Character than Dickens Himself?” (from Books in Motion, Adaptation, Intertextuality, Authorship (2005)), wrote about Bogarde’s theatricality in this film in relation to camp. Libel’s references to camp are more overt. Frank is after all, an actor, and excuses his impersonation of Mark by claiming that he is practicing for the ‘camp’ concert. Many films set in prisoner of war camps show its inmates spending what might seem like an inordinate amount of time on such entertainments, including quite often female impersonation; for us though, the use of the word ‘camp’ had an obvious double meaning.

Frank has less depth than the character of Mark – Mark is after all not sure who he is – but the relation to Bogarde’s real life is intriguing. Bogarde too started as a provincial actor (in repertory at Amersham – see one of my posts on the NORMMA blog: http://www.normmanetwork.com/pre-search-dirk-bogardes-life-and-career/). It is also important to consider our reading of Libel in relation to revelations made after his death about his private life. The reading of some of the aspects in Libel as elating to homosexuality is also strengthened by Bogarde’s later screen image – especially his appearance as a gay man in Victim (1961, Basil Dearden).

Frank has less depth than the character of Mark – Mark is after all not sure who he is – but the relation to Bogarde’s real life is intriguing. Bogarde too started as a provincial actor (in repertory at Amersham – see one of my posts on the NORMMA blog: http://www.normmanetwork.com/pre-search-dirk-bogardes-life-and-career/). It is also important to consider our reading of Libel in relation to revelations made after his death about his private life. The reading of some of the aspects in Libel as elating to homosexuality is also strengthened by Bogarde’s later screen image – especially his appearance as a gay man in Victim (1961, Basil Dearden).

We concluded our discussion by pondering the film’s own raising of the matter of scandal – it is for this reason that Mark launches the libel action against a ‘sensationalist’ newspaper. While this type of publication is distinct from the celebrity scandal magazines which especially proliferated in the 1950s, we spoke about the tricky line stars sometimes had to negotiate. Stars relied on print to sustain the public’s interest in them, but also had to be careful in case revelations about their private lives harmed their careers. We commented that in Libel the scandal was connected to class. Class runs through the film. We are introduced to Mark, by Richard Dimbleby, as a Baronet with a long family history, and a palatial stately home (in fact Longleat House). It is because of his family name that he is a prominent person – one readers may be interested to learn more about.

We concluded our discussion by pondering the film’s own raising of the matter of scandal – it is for this reason that Mark launches the libel action against a ‘sensationalist’ newspaper. While this type of publication is distinct from the celebrity scandal magazines which especially proliferated in the 1950s, we spoke about the tricky line stars sometimes had to negotiate. Stars relied on print to sustain the public’s interest in them, but also had to be careful in case revelations about their private lives harmed their careers. We commented that in Libel the scandal was connected to class. Class runs through the film. We are introduced to Mark, by Richard Dimbleby, as a Baronet with a long family history, and a palatial stately home (in fact Longleat House). It is because of his family name that he is a prominent person – one readers may be interested to learn more about.

We also spoke about how the film commented on publicity as a particularly American phenomenon. Although she claims she only wants to protect their son’s future, his wife is criticised by those attending the local church for the fact the libel action goes ahead – it is said that Americans love publicity. Significantly, Mark’s American wife is played by the American star de Havilland. British fan magazine Picturegoer noted that Libel continued Bogarde’s run of American sponsored films which would also be shown in the United States (29th August 1959). These included the already-made The Doctor’s Dilemma, and the upcoming The Franz Liszt Story – later renamed Song Without End (1960, Charles Vidor; George Cukor).

We also spoke about how the film commented on publicity as a particularly American phenomenon. Although she claims she only wants to protect their son’s future, his wife is criticised by those attending the local church for the fact the libel action goes ahead – it is said that Americans love publicity. Significantly, Mark’s American wife is played by the American star de Havilland. British fan magazine Picturegoer noted that Libel continued Bogarde’s run of American sponsored films which would also be shown in the United States (29th August 1959). These included the already-made The Doctor’s Dilemma, and the upcoming The Franz Liszt Story – later renamed Song Without End (1960, Charles Vidor; George Cukor).

It was also remarked upon that it is somewhat ironic that de Havilland recently launched an unsuccessful libel action against the makers of the 2017 mini-series Feud. The TV production, about the relationship between Bette Davis (Susan Sarandon) and Joan Crawford (Jessica Lange), includes a characterisation of de Havilland (Davis’ co star and friend) by Catherine Zeta-Jones. De Havilland criticised the series for claiming she was a gossip and for its less than flattering depiction of her own relationship with her sister, fellow film star Joan Fontaine. This shows the importance of the matter of personal reputation to stars, as well as the mingling of screen and star images.

It was also remarked upon that it is somewhat ironic that de Havilland recently launched an unsuccessful libel action against the makers of the 2017 mini-series Feud. The TV production, about the relationship between Bette Davis (Susan Sarandon) and Joan Crawford (Jessica Lange), includes a characterisation of de Havilland (Davis’ co star and friend) by Catherine Zeta-Jones. De Havilland criticised the series for claiming she was a gossip and for its less than flattering depiction of her own relationship with her sister, fellow film star Joan Fontaine. This shows the importance of the matter of personal reputation to stars, as well as the mingling of screen and star images.

As ever, do log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk and let me know you’d like me to add your thoughts to the blog.