It seems like the summer was so long ago – and the discovery of William Harris’ letters from his trip around Europe. Even so, I’m still finding these letters intriguing – I hope that you are too!

By December 1821, William and his four friends – all architects – had reached Rome. Two of them had set out from Dover in June; they had acquired new friends as they journeyed through France, to Geneva, then south through Italy before arriving in Rome for the winter. Although William and his architect friends had hoped to go on to Greece to sample architecture of the classical style, the Greek War of Independence (from the Ottoman Empire) meant that travel there was too dangerous to contemplate. Instead, William, Mr Brooks and Mr Angell had decided to remain in Rome for three months, when they would journey on to Sicily.

William’s second letter to Rome

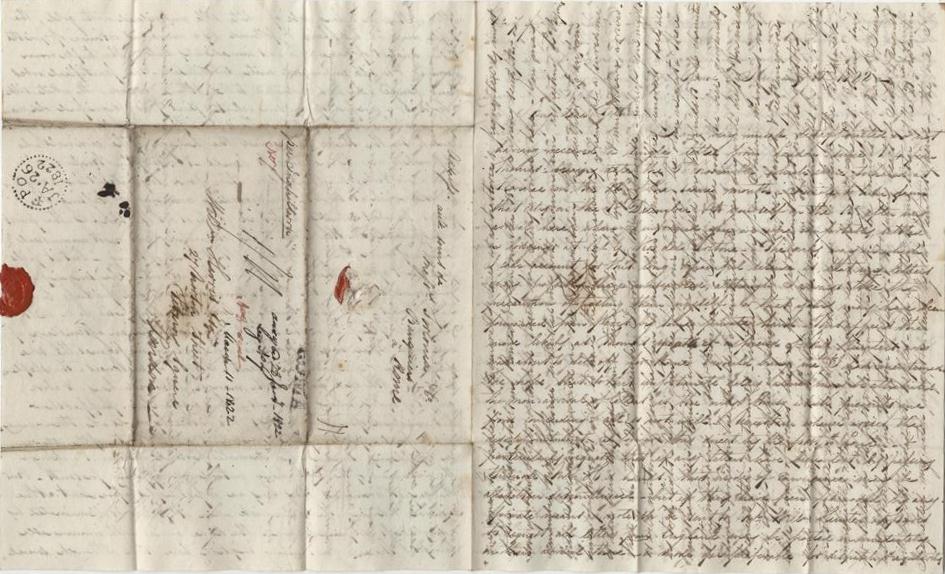

While we may think that the winter can be bleak in Britain, Rome in a nineteenth-century December, according to William, was not exactly exotic. He wrote again to his father on 10 January, ‘very much disappointed in not having received a single letter from London’ since the beginning of November. Whether it was homesickness, the distance from his family or simply the discomfort of the winter, William’s tone is unusually dismal – but still full of intriguing snippets. Since we’re coming up to Christmas, I thought William’s experience of the Roman festivities might be of interest.

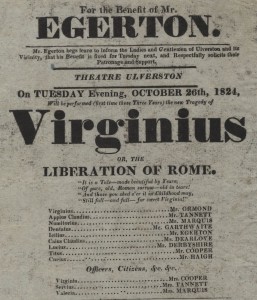

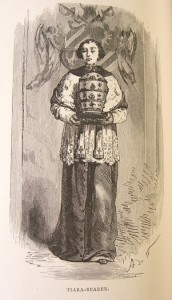

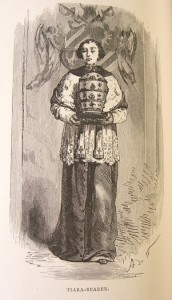

A papal tiara bearer, from ‘Rome’ by F. Wey, 1875

Evidently a staunch Protestant of the Church of England, William conceded that the Catholic ceremonies were ‘very splendid’. He visited the Pope’s chapel on the Quirinale Hill, where the Papal palace was used from the 16 century until around 1870. His first visit was on Christmas Eve, at a Mass which ‘was performed…with much grandeur’. On Christmas morning, William returned to the chapel for Mass, writing ‘I never witnessed a religious ceremony so nearly approaching a piece of acting as this’. Evidently he had been brought up in a rather more plain tradition.

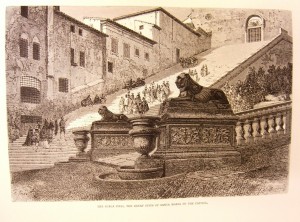

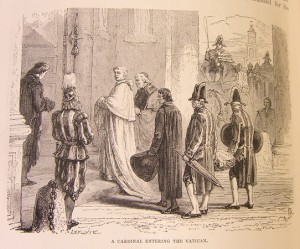

The cardinals wore scarlet robes with white fur capes and a scarlet skull cap and were each attended by a tiara bearer in a purple robe. They rose to receive each other as they arrived and took their seats in a line with their attendant tiara-bearers on a seat below them. The Pope entered soon after, clothed in a long robe of white silk embroidered with gold, the triple crown on his head and followed by a numerous retinue of priests and the senators of Rome. He was immediately seated, the triple crown removed and a silk embroidered mitre substituted. The pontifical robes being changed he was conducted to the throne covered with white silk and gold and a canopy of crimson velvet… On the throne he received the homage of the cardinals – who approached one by one to kiss hands – and also of the senators – who wear a wig and robes something like those of our serjeants at law, excepting the colour, which is scarlet.

Engraving of a cardinal, from ‘Rome’ by F. Wey, 1875

The Pope himself, Pius VII, seems to have impressed William; ‘Pius VII is a dignified old man of a very benevolent character’. Having become Pope in 1800, by 1821 Pius VII had reached the grand age of 79; it was hardly surprising that he was ‘too infirm to walk without assistance’. One of the ceremonies, William considered undignified: ‘the degrading ceremony of kissing the Pope’s toe was actually performed (at least on the shoe) by the priest who officiated at the altar.’ Other aspects of the Mass were more familiar, but still left William missing his customary style of worship;

The chaunting was most musical…but it falls far short of our cathedral service in this respect. The singing was fine enough but wanted the solemn organ to give fullness to the anthems.

The Mass was not the only unusual Christmas custom which William encountered in Rome

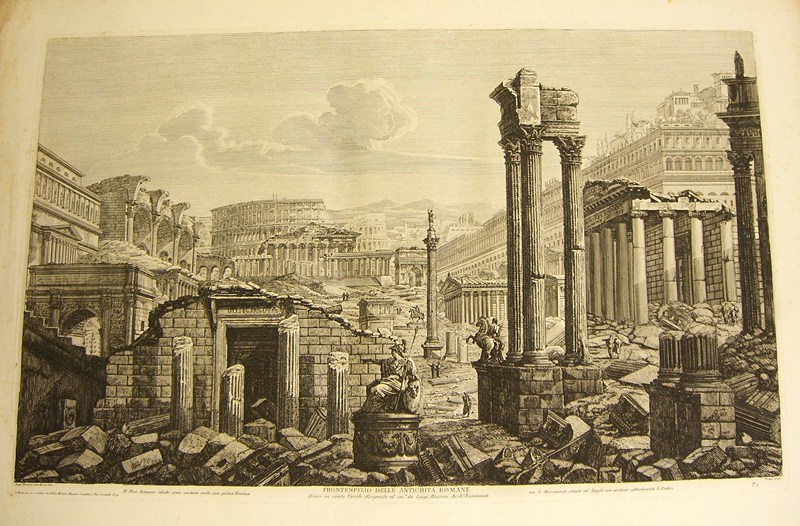

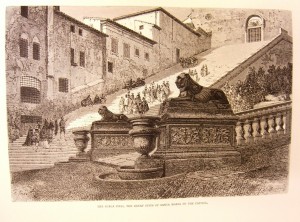

In the church of Ara-Coeli supposed to be built on the site of the temple of Jupiter on the Capitol – was exhibited an assemblage of wax work called here a ‘Presepio’ representing in size of life the Virgin with the infant – Joseph on his knees – the shepherds etc. etc. In the background was the manger, with real hay and above, groups of angels among the clouds.

The church appears to have been Santa Maria in Aracoeli, on the Capitoline Hill, previously a temple to Juno Moneta.

The steps leading up to the Ara Coeli from ‘Rome’ by F. Wey, 1875

This ‘presepio’, as you may have guessed, is a nativity scene, apparently largely unknown, at least in this larger incarnation, to William. These displays reached their apogee in the 19 century Kingdom of Naples – just a little earlier than William’s visit. Nowadays, we are used to these scenes – Canterbury Cathedral sets up its life-size model every year – but to William, this apparently Catholic practice was shocking:

This disgraceful puppet show has remained open several days and is visited by crowds who throw money into pewter platters placed to receive it in the centre of the stage.

It’s comments like this that make you realise how much things have changed in the last 200 years – and how Victorian our Christmas celebrations are now! In 1821, these festivities seem not to have impressed our English tourist, but he still had hope:

the gayest ceremonies they say are a fortnight before Lent at the carnival and during Easter week when St Peter’s is illuminated by a single cross suspended under the dome covered with innumerable lamps.

In spite of the season, there were still a number of English people in Rome. At the Mass on Christmas Eve, William met ‘Captain Grover of Norton Street’ – a neighbour back in London, I assume – while a number of English artists mingled at trattorias where William passed his time. At the Christmas Day Mass the congregation was finer still, with Cardinal Consalvi (Gonsalvi, in William’s letter), minister of the Papal States, and the Queen of Etruria, Marie Luisa of Spain who had been overthrown by Napoleon in 1807, in attendance.

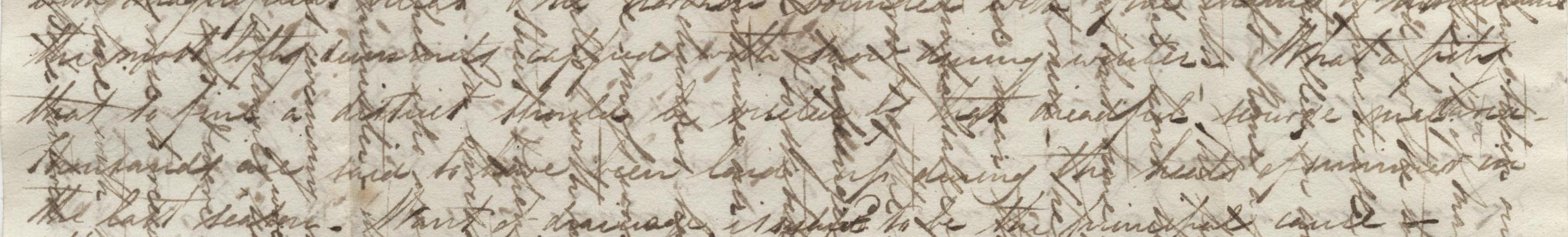

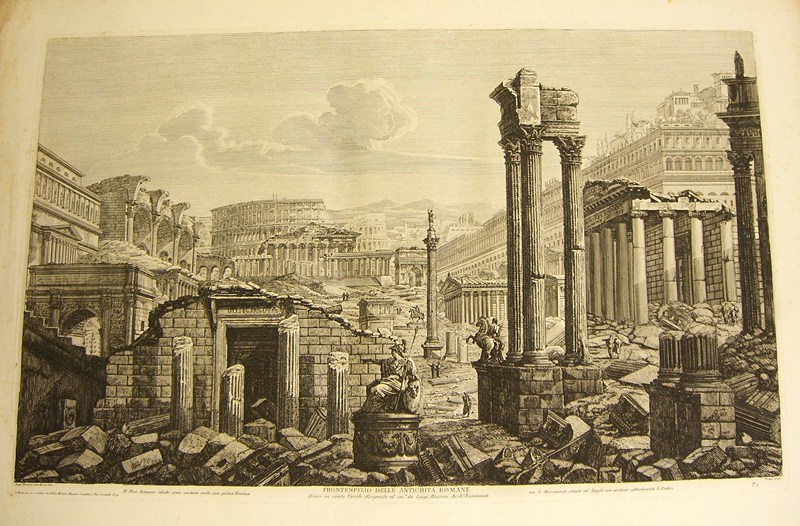

Illustration of the Roman Forum, from ‘Le antichita romane’ by Luigi Rossani, 1829

If the celebrities were shimmering, however, the weather certainly was not. Another particularly British trait which William possessed was a fascination with the weather and, while this had been fine when they arrived in Rome, by early January he complained: ‘lately there has been nothing but rain’. He went on:

The streets are…often overflowed near the banks of the Tiber and in some places almost impassable from streams of water pouring down from the roofs of the houses, each almost sufficient enough to drown the unfortunate passengers

All was not lost, however, since they still managed to ‘see a great deal and to sketch and measure a little’.

It may have been the weather, the season or his apparent isolation from his family, but in this letter, William seems to have been preoccupied with the morose. One paragraph begins ‘most of the funerals here are by torch-light’. I thought that the ostentatious fascination with death was a product of Queen Victoria’s reign, but the travellers evidently found the funeral traditions of Rome fascinating.

A very grand one [funeral] passed our lodgings the other night. There must have been a train of upwards of 300 monks and priests who chaunted as they moved along in their slow procession. In the centre was the bier gorgeously adorned, carried on the shoulders of penitents who wear long white dresses and a mask to conceal their countenances. On it lay the body of an Italian Marquis – not in a coffin but wrapped in funeral robes, the face, hands and feet uncovered while the crowd of torches shed a pale yet brilliant light on the ghastly scene.

In spite of his morose moments, William was entranced with the city of Rome. He had been told that that disappointment was the most common feeling on the part of tourists on seeing the city and was ‘agreeably surprised at finding much more scope for admiration’. Even without historical interest, William considered the city superior, designed on its seven hills to improve the aesthetic impact on the viewer. Even its outskirts were ‘graced with magnificent villas and the horizon bounded with fine chains of mountains the most lofty summits capped with snow during winter’. The only problem with the city, he wrote without premonition was ‘that dreadful scourge malaria. Thousands are said to have been laid up during the heats of summer in the last season.’

Urging his father to write soon, William signed off with love to his mother, sister and brother in law – and a request to send a watch and two books to Rome, in a packing case of fashionable clothes which Mr Brooks was having delivered from England. After all, a nineteenth century gentleman could not be seen measuring ancient monuments in last season’s coat.

Urging his father to write soon, William signed off with love to his mother, sister and brother in law – and a request to send a watch and two books to Rome, in a packing case of fashionable clothes which Mr Brooks was having delivered from England. After all, a nineteenth century gentleman could not be seen measuring ancient monuments in last season’s coat.

I hope you’ve enjoyed following the blog and all of our activities this year. It seems like just a few weeks since the first post of the year, when I wrote about the broadcasting of Restoration Man. Our year of Dickens has been eventful, productive and exciting. We look forward to welcoming you to the site, the collections and our events of 2013 – and also following William’s journey to its end, taking in Roman horse racing, Sicilian adventures, Mount Etna and an international scandal.

All the best wishes for the festive season!