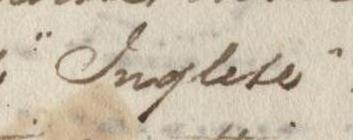

Exactly 191 years ago, William Harris, a young architect travelling around Europe, reached the city of Rome. Having explored ancient and more modern sites as he travelled from Dover to France, through Geneva and then Northern Italy, William waxed lyrical about the sites he’d seen, but none seem to have compared to his expectations of Rome.

Of course, the journey from Florence southwards was not without its share of excitement – the group of architects were eager to explore all that the country had to offer, from villas to volcanoes. The men employed a mule cart to transport their baggage and moved at a slow pace, allowing the men ‘plenty of excercise’; William added, ‘I think we must have walked a third of the way’. Having been warned about the poor quality of inns along the route, the friends were prepared for the worst, including a complete lack of tea. However, the warnings turned out to be ‘very much exaggerated’, although at one place they took a room ‘without any glass’ in its windows, in December. Being hardy souls, the men braved it: these hardships were of little consequence, William explained, since ‘we only slept there’.

Although there was indeed no tea to be found on the road, the architects discovered some ‘curious’ methods of making tea en route: ‘water boiled in a stewpan taken out with a soup ladle…tea made in a basin and drunk out of glasses without milk’. Travel, as the saying suggests, really does seem to have broadened these young architects’ minds.

The four architects also went to Siena, still scarred from an earthquake 31 years earlier. William noted ‘the ground is so irregular that the Baptistry is actually below the pavement of the chancel…and is approached from a different street’. Of the cathedral, however, William thought its ‘ornament is carried to excess but applied without taste’ – evidently not the clean, simple lines of perfection which the architect admired in classical buildings. The ornamented pavement, ‘in grey and white marble admirably contrasted’, depicting ‘scriptoral subjects’, impressed him. Still, with an abundance of common sense, he complained that although expending so much effort on the decoration of pavements was impressive, he pointed out that ‘it is impossible they can be seen to advantage.’

During his stay in Sienna, William also visited ‘the ‘Baths’ of St Phillippo formerly known to the Romans’. He wrote:

They are picturesquely situated among mountains and the water gushes from the natural soil with so great a heat that the hand cannot be borne in it more than half a minute – the steam rises from it as dense as boiling water strongly impregnated with sulphur and the surface all round is covered with thick calcareous deposate

Having read through several of these letters, I suspect that William discovered the heat of the water by sticking his hand in it. Architects in the nineteenth century were evidently thrill seakers; on hearing about a ‘cave of sulphur’, William decided to go and test its conditions for himself. He described;

a cleft…apparently immense in depth whence issues a strong sulphurous vapour and the heat is so great a few feet from the surface that in the space of one minute a pair of thick boots were insufficient to enable me to remain there.

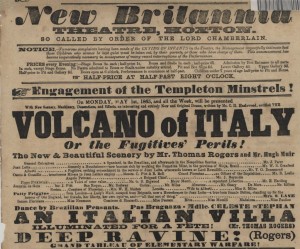

Forty years after William’s travels, the British public were still fascinated by Italian volcanoes, as this playbill shows

William went on: ‘a continued murmuring noise – no doubt proceeding from subterranean fires – was distinctly heard in this gloomy chasm’. I am beginning to wonder whether sending a lot of architects off to the continent served as a kind of natural selection – to ensure that the market back in ‘Old England’ didn’t get flooded with young professionals!

At Cassia, near Bolsena, the travellers visited a volcanic outcrop of rock similar to the Giant’s Causeway ‘and the cave of the Island of Staffa’. The only difference was that the Italian ‘curiosities…incline in various directions’, rather than being perpendicular: probably, William wrote ‘the result of some convulsion of nature’.

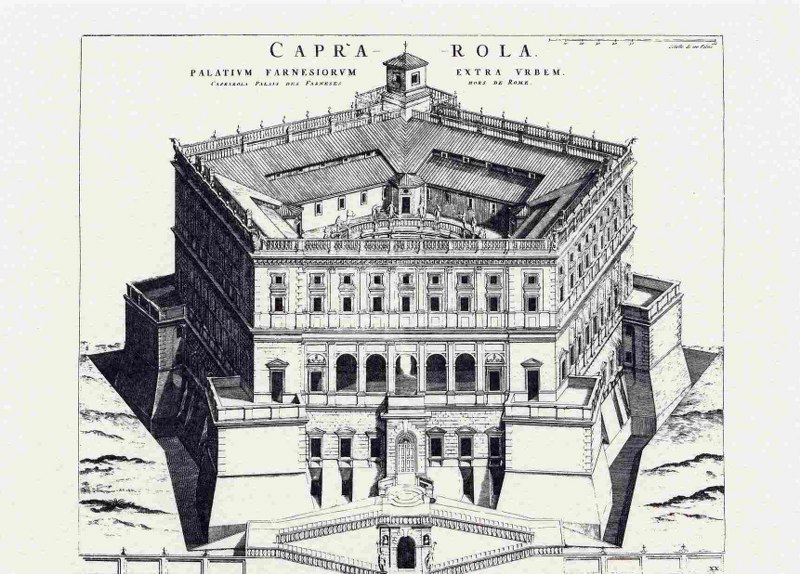

Of course, the dangers of nature were not the only perils which travellers faced in the nineteenth century. After leaving Bolsena, four of the group – William, Mr Brooks, Mr Angell and Mr Montague – left Mr Butts with the mules and the baggage to branch off and visit the villa of the King Naples. This pentagonal villa at Caprarola is known as the Palazzo Farnese and is less a villa than a small palace. William was, in general, impressed with the building and although ‘the gardens are deserted and neglected’, he noted to his father that they ‘have been laid out in the first style of Italian magnificence’. He also commented on a ‘curious style of decoration’ in some of the palazzo’s apartments: ‘huge maps are painted on them, covering the whole surface of the wall’.

Tired by their exploration of the lavish villa, William and his friends walked down to the village below and sought refreshment in ‘a little osteria’. There, they found themselves ‘in company with the most ill looking fellows I ever saw.’ He went on:

Some were enwrapped in the large Italian cloak and wore the high pointed Calabrian hat with a feather stuck in the band

Rather alarmed, the tourists discovered that there were bands of robbers operating in the area and, William recalled, ‘we had unthinkingly left our pistols in the carriage’. He worried that they ‘should have joined Mr Butts without our purses’, but these unsavoury men turned out to be two soldiers sent to safeguard travellers along the road. As luck would have it, William and his friends gained an escort back to their baggage: if they had been alone and met robbers, he joked to his father, ‘it would have been only ask and have’.

Without any further mishap, the architects caught their first glimpse of Rome at dawn on 10 December. William was evidently captivated:

From the heights…the distant farms of the city were seen illumed by the orb of day emerging from a fine chain of Appenines the loftiest of which were covered with snow. At every little eminence on the road the city gradually developed itself and the swelling dome of St Peter’s appeared in all its majesty.

Restraining himself from further description of the city so early in his acquaintance with it, William simply told his father ‘I am astounded and delighted with the magnificence of ancient and modern Rome.’ William’s ‘modern’ Rome is, of course, around 200 years earlier than what we would today consider the modern city.

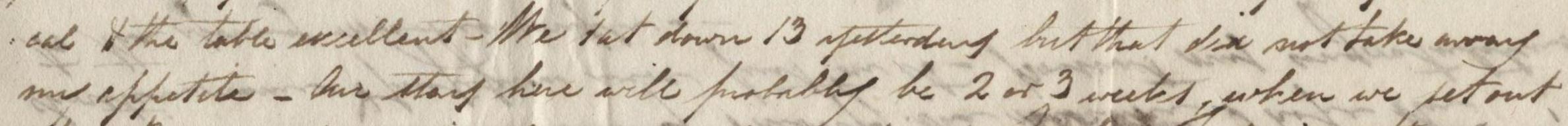

The men quickly settled into the city, Angell, Brooks and William sharing apartments on the Via del Tritone, while Montague and Butts remained at the Hotel d’Allemagne, since they intended to set off for Naples earlier than their friends.William related his concerns about this travel to his father, explaining that:

‘a day or two since…the courier from Rome to Naples had been stopped and two persons carried up into the mountains – a ransom being demanded for their liberation. How long will these wretches be suffered to carry on such horrid practices!’

William’s stay in Rome was intended to last for around 3 months: his intention was to be moving on in the spring ‘probably to Sicily – fearing there is but little hope of getting to Greece just at present’ due to wars in the area. Even so, the architects had prepared well and were not ready to give up on the hope of seeing Greece altogether: in Florence, they had ‘obtained some written directions and prescriptions from Dr. Down…good medical assistance is not easily obtained’. Remarkably, all of William’s party appear to have stayed in good health throughout their journey so far.

Closing his letter with ‘kindest love’ to all, William wrote that he hoped ‘to hear frequently from Old England during my residence’ in Rome. With the year coming to a close and planning to remain in Rome for several months, William was ready to spend Christmas in the city and looked forward to discovering all kinds of the weird and wonderful Italian customs before setting off for Sicily.

With a slight spoiler: William’s next letter is timely, describing Christmas in nineteenth century Rome…keep checking the blog for updates!