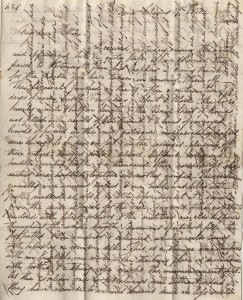

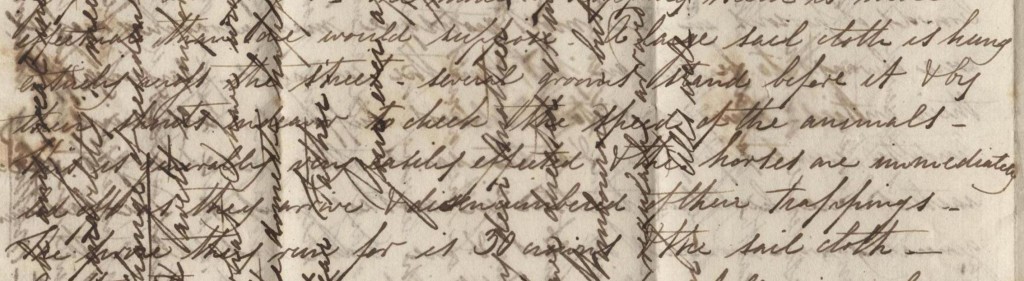

William usually over-wrote his letters to make the most of available paper

Well here we are in what finally feels like spring. The sun is shining, for now, and while I don’t suppose that it will last a week, it’s put me in mind of holidays and exotic locations once again. Those of you who’ve been following the series of posts recounting William Harris’ journeys around Europe in 1821-23 may remember that I started this series way back last summer, with a similar ‘holiday’ theme. In reality, William’s trip wasn’t a holiday but more of an extended gap year, on which he met a number of like minded young gentlemen, most of them architects, who spent their time exploring and frequently (if a little bizarre, to my un-architectural mind) measuring the remains of classical architecture around the Mediterranean.

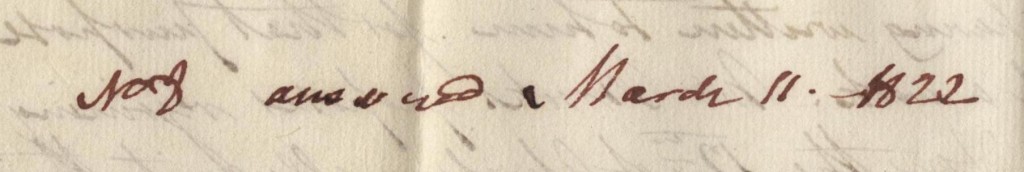

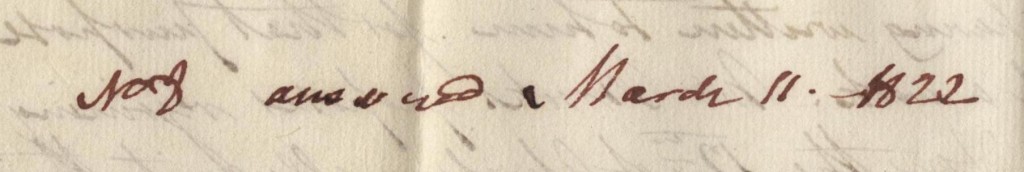

William’s story comes from a dozen or so letters written to his father back at home in London and recently discovered in the mysteriously named ‘Hansard Family deed box’. Unfortunately, we don’t have his father’s replies, but occasionally there are hints of the conversations which took place in the extant letters. Some of the replies evidently went astray; this is painfully clear in William’s previous letter from Rome, sent in January 1822, in which he wrote of the misery of being so far away from his loved ones. Probably in response to this, William’s father often annotated the received letters as ‘replied’ with a date, presumably to keep track of what had been sent.

William’s father noted the date of his reply

By the end of February 1822, William seems to have been in a more cheerful mood. He had received the package which he had requested from home in November, containing a watch, book and other ‘appendages’. It also seems that Rome itself was a more cheerful place to be – rather than the rain and funerals, the carnival season had come to the city.

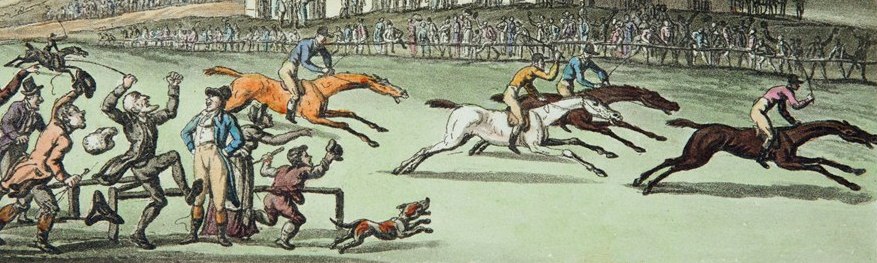

One of the highlights of the carnival was a horse race along the Via del Corso, noted by William as ‘the Bond Street of Rome’.

“About 7 o’clock the Corso nearly half a mile in length…was filled with crowds…. A little before sunset at a signal given the course is cleared for the race. The ends of the cross streets are closed with files of soldiers and the military…dispersed throughout the whole length. Numerous spectators fill the footpaths and windows and balconies, which are also hung with tapestries or crimson silk. This is a strange scene compared with an English racecourse.”

A Thomas Rowlandson illustration showing a British racecourse c.1820

William had, of course, a love of horses, witnessed in his concern about the lameness of one of the family ponies, named Dick, in earlier letters. This particular Roman race appears to have been a popular event since the fifteenth century, but it was somewhat alien to William’s cultural expectations. While debates over the humaneness of the Grand National continue, this race was a far cry from anything which William considered kind;

As the Italian race-horses always run without riders they have recourse to various means more or less cruel to urge their speed. A kind of spur is attached to their sides formed by a ball of lead stuck with spikes and fixed to the end of a short thong which beating against them goads the poor animals…. Fireworks also are sometimes fastened to them and large pieces of metal foil. Besides these instruments of torture, the horses are decked with ribbons.

Even in the nineteenth century, it’s clear that there were wide cultural differences in attitudes towards animals across Europe. Of course, goading the horses in this way could be as much danger to people as well: William reported that, ‘when led out for the race, some of them are so irritated as to require some 3 or so men to hold them…’

Without the need to impel the horses to start, the method of making them stop seemed to William still more bizarre:

A large sail cloth is hung entirely across the street – several grooms stand before it and by their shouts endeavour to check the speed of the animals.

Despite some of the animals getting outside the city walls and running for several miles before they could be stopped, in general, William considered this method of ending the race was ‘more effective than one would suppose’. The prize for the race was thirty crowns and the sail cloth.

Aside from being unnerved by Roman styles of horse racing, William evidently enjoyed the ‘confusion’ of the Carnival, which came to its end on 19 February 1822. He described streets ‘filled with pedestrians’ including ‘crowds of persons in the most grotesque masquerading dresses…huddled together in motley groups.’ ‘The coachmen’, William noted, ‘wore women’s dresses and one coach was filled with people masked as cats’.

As an educated gentleman with good connections, William was also privileged to be invited to a ‘very gay masked ball given by Torlonia’ at which the ‘rooms were brilliant and the dresses splendid’. The Torlonia family was a powerful banking family in Italy, and this particular Torlonia, probably Giovanni (1755-1829), administered the Vatican’s finances. Their wealth was evidently on display: William noted Torlonia’s ‘diamond buttons’ and that ‘the Duchess his wife was sparkling with finery’. ‘Many of the English and Italian nobility were there’, William commented airily, most of them in costume: ‘the young Torlonias danced as Peruvians in character-whimsical enough’.

Another of the honoured guests – somewhat higher up the social ladder than William himself – was ‘Prince Couburg who is to be seen everywhere.’ Evidently, the presence of Prince Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg (1785-1851) was nothing great to be commented on in Rome at that time, but we now know him as the uncle of both the later Queen Victoria (who was only 3 and a long way from the throne at this point) and her husband, Prince Albert.

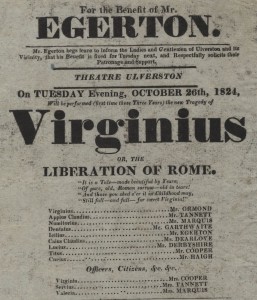

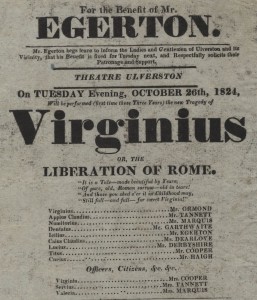

Virginius, or; the liberation of Rome This exotic location was used to advertise the play at Ulverston, 1824

Perhaps William’s buoyant mood also had something to do with his plans to move on from Rome after the long winter, to head to Sicily and discover new wonders. This meant the breaking up of their little group, gathered piecemeal from Calais onwards. Mr Butts (who avoided the near run-in with bandits near Naples by staying with the mules) and Mr Montagu (who had spent the summer cruising the Mediterranean in a brig of war) were returning to England via Northern Italy. Mr. Brooks, however, intended to come back to Rome from his visit to Florence in time to set off with Thomas Angell and William for Sicily in April. Their adventures – including climbing a volcano and sparking an international furore in the archaeological world – must wait until a later post, but I hope you still have time to hear an unusually personal note which William added to his letter the following morning.

We have surmised that Margaret, William’s sister, was married to a man named Thomas (another architect); some time between the 27 and the morning of 28 February, William received a letter from them which troubled him:

I am truly grieved to hear that circumstances have induced Thomas and my sister to think of letting their house and taking up their residence in the country

William evidently shared contemporaries’ mistrust of renting property

These ‘circumstances’, though they were apparently not spelled out in the letter, William had surmised to be ‘health and economy united’. The drive for economy, William feared, would prove futile, owing to the dangers of unreliable tenants, the expense of moving and ‘the damage which would almost inevitably accrue to their furniture when in the hands of strangers.’ Moving from the capital might also, William feared, have a negative impact on Thomas’ career and he also considered ‘the loss my poor Mother would suffer’. In the eloquent and painstakingly polite style of the time, William asked his father, who had ‘already done much’:

would it not be a satisfaction to you to reflect you had left nothing undone…?

Assuring his father that he requested this assistance to his sister ‘solely by my own convictions’ rather than any urging on any other behalf, ‘dictated by an ardent wish for the domestic happiness of all most dear to me’, he added;

may I not hope you will consider the matter and avert so unfortunate a circumstance

I don’t know why but I find it particularly touching that even halfway round the world on the trip of a lifetime, William clearly still felt the need to intervene and help his family, with real concern for their well-being. What happened to them is still to be discovered, with William setting off for Sicily in the hopes of new adventure – but I suspect that neither he nor his family could have imagined what would happen next.

Keep up to date with William’s adventures by checking the blog and keeping an eye on our Twitter feed @UoKSpecialColls

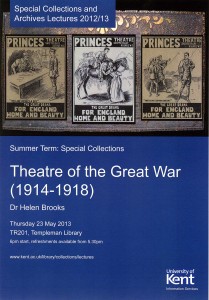

The launch was started with a lecture by Professor Kate Newey from the University of Exeter, who spoke about the subtle protest in suffragette parlour dramas and the deliberate inversion of the female stereotype by campaigners for womens emancipation. The event then moved to the gallery space in the Templeman Library, where everyone enjoyed this rare opportunity to see such different collections side by side.

The launch was started with a lecture by Professor Kate Newey from the University of Exeter, who spoke about the subtle protest in suffragette parlour dramas and the deliberate inversion of the female stereotype by campaigners for womens emancipation. The event then moved to the gallery space in the Templeman Library, where everyone enjoyed this rare opportunity to see such different collections side by side. This exhibition really is an intriguing and entertaining look at the way in which perceptions of women and society as a whole were being challenged a century ago and is only on until 31st May, so please do come and have a look around when you’re next in the Templeman.

This exhibition really is an intriguing and entertaining look at the way in which perceptions of women and society as a whole were being challenged a century ago and is only on until 31st May, so please do come and have a look around when you’re next in the Templeman.