[This blog has been written by Amy Green – a volunteer at Special Collections and Archives who was instrumental in planning and writing our exhibition about Mining in Kent. Amy added a personal story to the exhibition – describing the circumstances of the death of her Great Grandfather, who died in an accident in Betteshanger mine in 1934. It is through personal stories and connections such as Amy’s that the material in the archives are often brought to life – and we are grateful that Amy and her family shared their story with us.]

As a volunteer at the University of Kent archives, I am happy to have taken part in this display, which includes my connection with Kent Mining.

Before my grandfather passed away in 2021, we took it upon ourselves to research our family tree. My family all have links to Deal later in life.

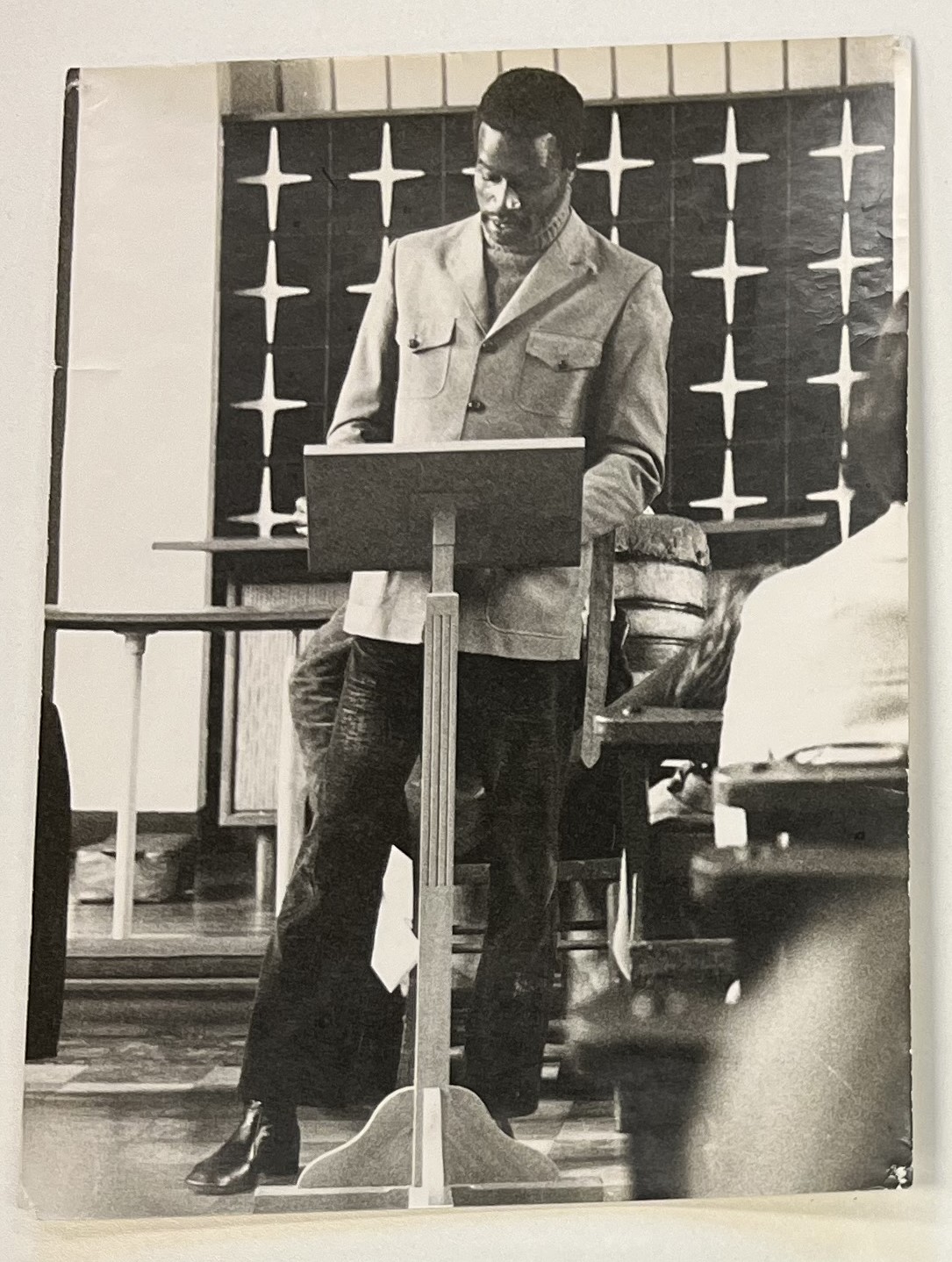

The following connection was established to a miner named Cephas Thorpe, my great-grandfather.

Cephas Thorpe – image provided by the family of Amy Green

Cephas moved from Attercliffe, Yorkshire, to Deal, joining Betteshanger Colliery in 1933. As a miner, you go where the work is. Many would have walked from their homes, as public transport was not what we have today! This averages 248 miles, moving his small family to Deal.

His career began in WW1, after following his father’s footsteps in mining. It is believed the regiment Cephas served under was the York and Lancaster Regiment, who were also part of The Tunnellers during WW1. He earned a victory medal for his service during the war which was given to those who served. He was medically dismissed for his age in 1920.[1]

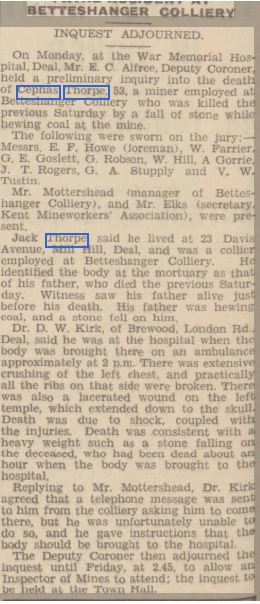

As a miner in Betteshanger, his time here was tragically cut short by an accident in 1934. Whilst hewing[2] coal at the mine, a lump of rock came loose, falling on Cephas, fatally crushing him. In Cephas’s inquest hearing, taken from a clipping from the Dover Express, Dr DW Kirk explains Cephas’ injuries, which were a combination of fatal crush and head injuries.

Clipping of report of the inquest into the death of Cephas Thorpe at Betteshanger in 1934

Life as a miner was always something of a risk; it had challenging circumstances. During the period of 1930-50, health and safety was yet to progress to the standard we are now lucky to have today to reduce such industry deaths. Mining had risks not only physically health but mental health as well. The physical dangers were clear, with incidents such as rock falls, explosions, and cave ins. Miners were also regularly exposed to harmful contaminants, and experienced very poor air quality, which was dangerous on its own. Without enough oxygen to the brain, headaches, nausea, and dizziness will occur, and can ultimately result in death when the oxygen concentration drops below 6%. This was a reason for regular breaks for miners and shift changes, depending how long you had spent down the mine.

Although only accounting for one percent of the global workforce today, it is responsible for about eight percent of fatal accidents at work. [3]

[1] At the time of publishing, family research is still ongoing.

[2] hewing is a mining term meaning to strike or blow with an axe or sword.

[3] International Labor organisation, 23, March 2015. https://www.ilo.org/safework/areasofwork/hazardous-work/WCMS_356567/lang–en/index.htm