Our thoughts about the film ranged over several topics: the film’s setting, including time, space and place; the gothic heroine; her husband; their children; the plot twist(s); other gothic films.

We began with discussion of the film’s setting. A title identifies the action as occurring in Jersey in 1945. The Channel Island location mostly seems significant in terms of its isolation and the unusual liminal position it held during World War II: it was British territory, but occupied by the Germans. This allows the film a connection to gothic of Britain past. The link to past gothic films is heightened by the 1945 date – a time at which many gothic films were popular in Britain and the US.

Discussion also centred on just what aspect of the film the 1945 date setting referred to. While there are no flashbacks, the film’s structuring of time is complex as it is revealed that most of the characters are no longer living, with their deaths having taken place at various points in the past. The main family appears to have died some time between the beginning and the end of World War II, with the heroine Grace (Nicole Kidman) mentioning that the staff has left in the last week. In retrospect, we can see this as relating to the time of her and the children’s (Ann and Nicholas’) deaths. The ghostly staff replacements’ date of death is more concretely asserted – Grace finds a photograph dated 1891 of housekeeper Bertha Mills, gardener Mr Tuttle, and housemaid Lydia posed after death from tuberculosis.

relating to the time of her and the children’s (Ann and Nicholas’) deaths. The ghostly staff replacements’ date of death is more concretely asserted – Grace finds a photograph dated 1891 of housekeeper Bertha Mills, gardener Mr Tuttle, and housemaid Lydia posed after death from tuberculosis.

The gulf in time between these sets of characters was especially interesting. We noticed that the film gave good reason for the lack of technology, the presence of which might have confused the older staff. Grace says that they have got used to not having electricity since the occupation, while the children’s supposed photosensitivity means they cannot be subjected to more than dull candlelight. The lack of a telephone and automobile also makes the fact that nobody calls more understandable – it both makes smoothes over the fact that the main family is only recognised by the three older ghostly staff and increases the whole household’s isolation.

Space is especially important to the film, not just in terms of its isolated Jersey manor house setting, but the specific way in which Grace, Ann and Nicholas, as well as Mrs Mills, Mr Tuttle, and Lydia are all bound to the area of the house. The suitably gothic fog is complicit in this. While the ghostly staff is tied to the house by their duties, the children by their photosensitivity and Grace to a large extent by her status as mother, on the one occasion she leaves the house she is hemmed in by oppressive fog. Mrs Mills is signals that this is a deliberate instrument to prevent Grace from reaching the outside world. This is unsettling, as it causes us to question what is going on, and this is reinforced by the film’s camerawork on the two occasions characters attempt to leave. When Grace sets out in the fog she appears to both leave the house and happen upon it without changing direction- almost making it seem that the building on screen is a  neighbouring manor house. The children leave in the dark and they too end up looping around the house. The camerawork suggests they are getting away from the house, but they return to it, and the gravestones revealing the deaths of Mrs Mills, Mr Tuttle, and Lydia.

neighbouring manor house. The children leave in the dark and they too end up looping around the house. The camerawork suggests they are getting away from the house, but they return to it, and the gravestones revealing the deaths of Mrs Mills, Mr Tuttle, and Lydia.

This lack of mobility, or the sense of characters trapped in space, led us to discuss this matter more. We thought it was especially significant that while the ghostly staff, Grace and the children are limited to their place of death – the house and its environs – Grace’s husband Charles (Christopher Ecclestone) manages to escape the front where he has been killed to meet Grace in the fog on his return home. He states that this is what he has been looking for. While the gardener Mr Tuttle also has more mobility than his female counterparts Mrs Mills and Lydia, like them he is afforded no class mobility. All three are not only confined to the area of the manor house they previously worked, but to working for the new lady of the house– they do not get to rise above their class situation.

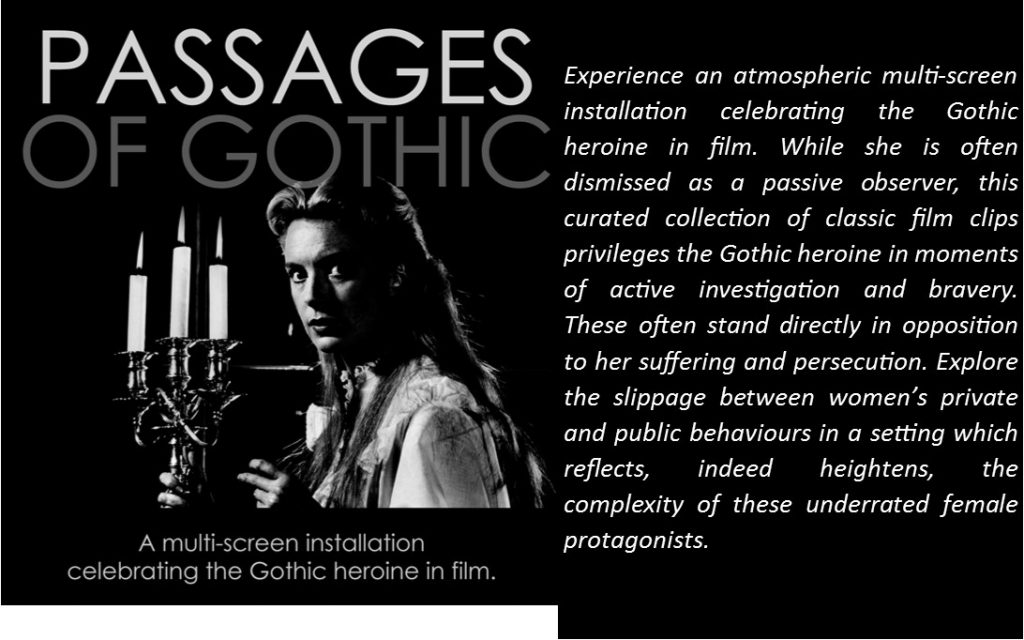

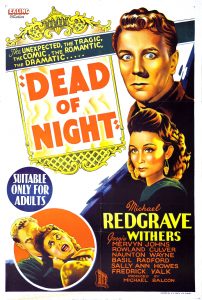

We especially focused on Grace’s status as gothic heroine. While the mother is fairly unusual in terms of gothic film (it does not occur in Rebecca (1940), Gaslight (1940 and 1944), The Spiral Staircase (1945), or Secret Beyond the Door (1947)) other aspects connect Grace to the genre. She is a woman in peril, seemingly beset by ghostly intruders (actually the new owners of the house) against whom she actively takes up arms – a shotgun. It is also feared, by her, and us, that she is going mad. It later turns out this had indeed previously happened as the children died after she smothered them with pillows and she consequently committed suicide with a shotgun. There also seem to be specific nods to the gothic film of the 1940s with an especially striking scene in  which Grace in dressed in a white nightgown, lamp in hand, as she investigates the goings on. (See previous posts on gothic films we’ve watched for discussion of similar scenes, as well as the 20 minute video essay Passages of Gothic which you can view here https://vimeo.com/170080190)

which Grace in dressed in a white nightgown, lamp in hand, as she investigates the goings on. (See previous posts on gothic films we’ve watched for discussion of similar scenes, as well as the 20 minute video essay Passages of Gothic which you can view here https://vimeo.com/170080190)

Grace’s relationship with her husband is also unusual in comparison to the 1940s gothic film. While in Rebecca, Secret Beyond the Door, and others, the heroine is in danger from her husband, in The Others he is absent for a large part of the narrative. When he returns this appears, as indeed it is, unlikely, seemingly summoned by Grace’s desire. We wondered what the point of Charles’ return was. While he does reunite with his family and they are overjoyed to see him, he is distressed, spending much time unable to get out of bed. We were unsure whether this related to post traumatic stress due to the war or if he had an inkling as to his own death, and perhaps those of his family members. It was noted that he confronts Grace about her slapping the children in the  past, after Ann relates this to him, and it was raised that perhaps this signalled his knowledge of Grace’s killing of the children. We also discussed Charles’ swift departure. Perhaps this signalled some kind of resolution for him, or Grace, though it seemed a little hurried.

past, after Ann relates this to him, and it was raised that perhaps this signalled his knowledge of Grace’s killing of the children. We also discussed Charles’ swift departure. Perhaps this signalled some kind of resolution for him, or Grace, though it seemed a little hurried.

The children were another interesting departure from gothic films. While they seemed grounded and modern in some ways (we especially appreciated Ann’s logic in arguing for her interpretation of the bible) there were moments they appeared more like the creepy of films such as The Innocents (1961). There are times it seems that Ann might be ‘gaslighting’ her mother since she tells her of the intruders only visible to her – and not the audience. An especially disturbing scene occurs when Ann, dressed in her first holy communion dress, is possessed by the medium attempting to make contact with the family. The time Ann is supposedly possessed by new resident Victor is more complex. In retrospect it seems unlikely that the young boy would have the same skillset as the medium – and since we only hear Ann with Victor’s voice while she faces away from her brother Nicholas we can suppose that, as in other parts of the film, she is tricking Nicholas in order to scare him. While not a very sisterly action, this has the feel of a childish prank rather than a truly creepy occurrence.

skillset as the medium – and since we only hear Ann with Victor’s voice while she faces away from her brother Nicholas we can suppose that, as in other parts of the film, she is tricking Nicholas in order to scare him. While not a very sisterly action, this has the feel of a childish prank rather than a truly creepy occurrence.

We also debated the children’s alleged photosensitivity. In addition to the fact any previous exposure does not appear to have affected them (there are no sores on either child’s skin) we wondered just how aware people would have been of the condition in the 1940s. It serves the narrative, however, to keep the children in the house without having to explain why they cannot leave the grounds. It also keeps them close to Grace. We instead considered the light Grace wanted to keep herself and her children from was metaphorical – the awful truth of their non-living status and Grace’s responsibility for this.

It is especially interesting that the truth should be revealed when the curtains supposedly protecting the children from the sunlight disappear. This is a moment of horror for Grace, and this is indeed played with panic by Kidman. The connection of the curtains to the matter of domestic setting, and arguably female furnishings, is significant. Taking the line ‘Where are the curtains?’ out of its context strips it of its intensity, reducing it to a possibly trivial household inquiry. Spoken with urgency, but without knowledge of Grace’s fears, we thought it would well suit a parodic melodrama.

It is especially interesting that the truth should be revealed when the curtains supposedly protecting the children from the sunlight disappear. This is a moment of horror for Grace, and this is indeed played with panic by Kidman. The connection of the curtains to the matter of domestic setting, and arguably female furnishings, is significant. Taking the line ‘Where are the curtains?’ out of its context strips it of its intensity, reducing it to a possibly trivial household inquiry. Spoken with urgency, but without knowledge of Grace’s fears, we thought it would well suit a parodic melodrama.

While this whole summary has included spoilers (sorry!) some of us who had not already seen the film were aware of the twist that the family and the servants were ghosts; furthermore we suspected that they were the intruders with the supposed intruders actually the new living owners. The manner of the Grace and the children’s deaths was a surprise though. They clearly all perished at the same time, but the fact that Grace killed her children and then herself was shocking. An attack by the Nazis seemed more likely. This revelation turns Grace’s whole gothic woman-in-peril status on its head. While we might feel sympathy for her, presumably she was unbalanced and distraught at her husband not returning from the war, it is she and not her husband, the intruders or the medium, who is the danger.

While we noted some differences from the 1940s gothic – the presence of the mother, the mostly absent husband, the fact Grace is not a woman in peril in the end, there are clearly aspects of the gothic the film knowingly draws on. In addition to the isolated manor house, Grace’s possible gaslighting, there is an emphasis on containment. Grace is obsessed with locked rooms, and keys, which speak to the fact she is keeping herself and the children from the ultimate secret – her actions. There is also the unusual fact that the supposedly ghostly goings on are indeed ghostly goings on –though the ghosts are not necessarily the people we suspect. They are not the result of Grace’s imagination or her persecution by her husband. We also thought the scene in which Grace is dressed in a white nightgown, lighting her way with a lamp during her active investigation, was a nod to the 1940s films and The Innocents. We contemplated that the mute Lydia was perhaps a reference to the heroine in The Spiral Staircase.

Grace is dressed in a white nightgown, lighting her way with a lamp during her active investigation, was a nod to the 1940s films and The Innocents. We contemplated that the mute Lydia was perhaps a reference to the heroine in The Spiral Staircase.

We were also reminded of more recent gothic films. Grace’s response to a suggestion that she has left a door unlocked, leading to the possible exposure of her children to damaging sunlight, ‘Do you think I’d do such a thing?’ is an important turning point. When we learn of just what Grace has done, it seems less like gaslighting and more that she is beginning to realise what she has done. Our knowledge then reframes the early scene of Grace waking up screaming and her response to the panicked breathing of her children. Grace’s screaming is especially intense, but she does not reflect on this. Other aspects appear to seep through, however. Grace admonishes Ann for her quick shallow breathing at the dinner table, and later Ann similarly tells off Nicholas for comparable behaviour. It is possible this is linked to how Grace killed them – their hastened breathing in response to her smothering of them with pillows. We connected this return of the repressed to the film The Awakening (2011) in which the heroine is walked through her childhood home, and the passages of her mind, in order to remember her past and move on. In fact, perhaps all of this is occurring in Grace’s mind. Such a view is supported by the fact Grace finds so many veiled items in the junk room of the mansion a surprise. While she has presumably lived there for a while, she has only just stumbled across the books of the dead- photographs of posed dead people. She is understandably shocked by these

We were also reminded of more recent gothic films. Grace’s response to a suggestion that she has left a door unlocked, leading to the possible exposure of her children to damaging sunlight, ‘Do you think I’d do such a thing?’ is an important turning point. When we learn of just what Grace has done, it seems less like gaslighting and more that she is beginning to realise what she has done. Our knowledge then reframes the early scene of Grace waking up screaming and her response to the panicked breathing of her children. Grace’s screaming is especially intense, but she does not reflect on this. Other aspects appear to seep through, however. Grace admonishes Ann for her quick shallow breathing at the dinner table, and later Ann similarly tells off Nicholas for comparable behaviour. It is possible this is linked to how Grace killed them – their hastened breathing in response to her smothering of them with pillows. We connected this return of the repressed to the film The Awakening (2011) in which the heroine is walked through her childhood home, and the passages of her mind, in order to remember her past and move on. In fact, perhaps all of this is occurring in Grace’s mind. Such a view is supported by the fact Grace finds so many veiled items in the junk room of the mansion a surprise. While she has presumably lived there for a while, she has only just stumbled across the books of the dead- photographs of posed dead people. She is understandably shocked by these macabre pictures, and later finally recognises the truth of the ghostly servants when she discovers their photograph hidden under Mrs Mills’ mattress. The notion that this is taking place in Grace’s mind may seem to undermine the earlier assertion that Grace is not imagining the goings on. But it simply points to the complexity of the film, its relation to the gothic and its conscious referencing of earlier gothic films.

macabre pictures, and later finally recognises the truth of the ghostly servants when she discovers their photograph hidden under Mrs Mills’ mattress. The notion that this is taking place in Grace’s mind may seem to undermine the earlier assertion that Grace is not imagining the goings on. But it simply points to the complexity of the film, its relation to the gothic and its conscious referencing of earlier gothic films.

As ever, do log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.