Posted by Sarah

The titles and abstracts for our upcoming Maternal Melodrama on the 3rd of June:

Pam Cook, University of Southampton, Film Studies

“Paratext and Subtext: Reading Mildred Pierce as Maternal Melodrama”

Maternal melodrama has  generated an influential body of critical writing that examines the implications of its representations of motherhood for women. Ambivalence towards and desire for mothers continue to inspire stories of maternal suffering, self-sacrifice, guilt and blame that have a powerful emotional appeal. I’ll focus on Mildred Pierce to try to get to the heart of why this genre (cycle?) is so significant and how a diverse collection of films comes to be viewed as maternal melodrama. Using my videographic work, I’ll look at the role of paratexts (Genette) in producing the subtexts that point to the genre’s transgressive potential.

generated an influential body of critical writing that examines the implications of its representations of motherhood for women. Ambivalence towards and desire for mothers continue to inspire stories of maternal suffering, self-sacrifice, guilt and blame that have a powerful emotional appeal. I’ll focus on Mildred Pierce to try to get to the heart of why this genre (cycle?) is so significant and how a diverse collection of films comes to be viewed as maternal melodrama. Using my videographic work, I’ll look at the role of paratexts (Genette) in producing the subtexts that point to the genre’s transgressive potential.

Catherine Grant, University of Sussex, Film Studies

“Studying Old and New Maternal Melodramas Videographically”

In my talk, I will screen a number of my short audiovisual essays on film melodramas which centrally feature mother-daughter relationships (including two cinematic adaptations of Olive Higgins Prouty’s 1922 novel Stella Dallas [1925 and 1937], The Railway Children [1970], and Andrea Arnold’s 2009 film Fish Tank).

I will also explore what “creative critical” videographic methods can bring to the study of old and new maternal melodramas. I will argue not only for the greater potential of audiovisual expression for richer and more precise engagements with the motifs and textures of film melodrama, but also for the benefits of methods which more evidently express, and at times productively foreground, the subjective and affective investments of the individual researcher.

For an example of Katie’s videographic essays on Melodrama please visit her fantastic Film Studies For Free blog, especially the post ‘Voluptuous Masochism: Gothic Melodrama Studies in Memory of Joan Fontaine’:

http://filmstudiesforfree.blogspot.co.uk/2013/12/voluptuous-masochism-gothic-melodrama.html

Keeley Saunders, University of Kent, Film Studies (ks424@kent.ac.uk)

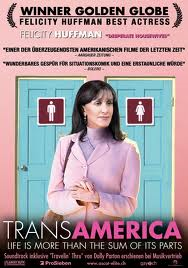

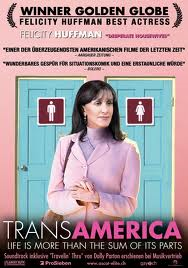

“Transitioning and the Maternal Melodrama: Parental Roles in Transamerica”

In the process of transitioning, many transgender individuals have to learn how to manage their new identity in society: dealing with other people’s perceptions of them, moving jobs or location, or significantly, ‘coming out’ to their family. Trans memoirs, such as Stuck in the Middle with You by Jennifer Finney Boylan, detail the complex process of transitioning as a parent: for Boylan, moving from ‘father’ to ‘mother,’ with a period in between where the subject occupied neither – or both – positions. Documenting this issue draws attention to the traditional roles of gender and the social structures policing gendered parenting responsibilities or behaviours. Elsewhere this can be depicted through a parent’s response to their child coming out and their reaction (and the relationship developed) following such an announcement.

Family dynamics and the role of the parent is a recurring narrative trope within the fictional mode of ‘trans-cinema.’ Transamerica (Duncan Tucker, 2005)  presents both of sides of the parental dynamic outlined above, following Bree, a pre-operative trans woman who is in the process of transitioning. This presentation will explore how Transamerica – and trans-cinema more broadly – adopts various melodramatic structures to portray its narratives. With particular reference to the characterisation and role of the mother, I will address how the film utilises the convention of parental roles, situating Bree as both the estranged parent and the estranged child attempting to (reluctantly) reconnect with her family before she undergoes her surgery.

presents both of sides of the parental dynamic outlined above, following Bree, a pre-operative trans woman who is in the process of transitioning. This presentation will explore how Transamerica – and trans-cinema more broadly – adopts various melodramatic structures to portray its narratives. With particular reference to the characterisation and role of the mother, I will address how the film utilises the convention of parental roles, situating Bree as both the estranged parent and the estranged child attempting to (reluctantly) reconnect with her family before she undergoes her surgery.

Lavinia Brydon, University of Kent, Film Studies

“The Suffering and Sacrifices of a Mother (Country): Examining the Scarred Irish Landscape in The Last September (1999)”

This paper seeks to investigate  and interpret the melodramatic tendencies of The Last September (Deborah Warner, 1999), an Anglo-Irish heritage film set just one year prior to the Ireland’s partition in 1921-1922. Taking John Hill’s comments on the melodramatic excess of the similarly concerned Fools of Fortune (Pat O’Connor, 1990) as a starting point, this paper will consider how the violence of the period complicates the restraint that typically marks the heritage film. Indeed, it will argue that the turbulent time frame permits the ‘astonishing twists and turns of fate, suspense, disaster and tragedy’ (Mercer and Shingler 2004: 7) for which early theatrical melodramas were famed. However, given the familiar nationalist allegory of Ireland as a poor old woman (otherwise known as Cathleen ni Houlihan), this paper will move on to consider how the violence inscribed on the Irish landscape allows the film to be framed specifically as a maternal melodrama. It will thus consider how the film depicts the suffering of and sacrifices made by Ireland as a mother (country).

and interpret the melodramatic tendencies of The Last September (Deborah Warner, 1999), an Anglo-Irish heritage film set just one year prior to the Ireland’s partition in 1921-1922. Taking John Hill’s comments on the melodramatic excess of the similarly concerned Fools of Fortune (Pat O’Connor, 1990) as a starting point, this paper will consider how the violence of the period complicates the restraint that typically marks the heritage film. Indeed, it will argue that the turbulent time frame permits the ‘astonishing twists and turns of fate, suspense, disaster and tragedy’ (Mercer and Shingler 2004: 7) for which early theatrical melodramas were famed. However, given the familiar nationalist allegory of Ireland as a poor old woman (otherwise known as Cathleen ni Houlihan), this paper will move on to consider how the violence inscribed on the Irish landscape allows the film to be framed specifically as a maternal melodrama. It will thus consider how the film depicts the suffering of and sacrifices made by Ireland as a mother (country).

Tamar Jeffers McDonald, University of Kent, Film Studies

“All That Costume Allows: Does Dress Tell the Mother’s Story?”

As its title suggests, this short paper seeks to link two famous Film Studies texts: Douglas Sirk’s 1955 melodrama, All That Heaven Allows, and Jane Gaines’ 1991 article, “Costume and Narrative: How dress tells the woman’s story”. Gaines’ piece insists that, because of the gendered division of narrative agency inevitably operating in Classical Hollywood Cinema, character is conveyed in different ways; men, who are active in the narrative, making things happen, are summed up by those happenings, but women, who are passive and acted upon, cannot thus be known. Their characters need to be made apparent to the viewer through other means: Hollywood has traditionally used costume. As Gaines remarks, “a woman’s dress and demeanour, much more than a man’s, indexes psychology: if costume represents interiority, it is she who is turned inside out on screen.” (Gaines, 1991: 181)

On first consideration, Sirk’s scenario – about a widow’s romance with a younger man seen, by her children and snobbish community, as her social inferior – appears ripe to contest Gaines’s assertions. The film is all about Cary Scott, the central female character, her feelings, motives, decisions. Her status as a mother surely endows her with agency, as she cares for her children and, true to the maternal melodrama formula, sacrifices her own happiness to ensure theirs? Does the film need to employ the ‘storytelling wardrobe’ for a character so at the heart of the story, even when she is female? This presentation examines Cary’s costumes in detail to find out.

On first consideration, Sirk’s scenario – about a widow’s romance with a younger man seen, by her children and snobbish community, as her social inferior – appears ripe to contest Gaines’s assertions. The film is all about Cary Scott, the central female character, her feelings, motives, decisions. Her status as a mother surely endows her with agency, as she cares for her children and, true to the maternal melodrama formula, sacrifices her own happiness to ensure theirs? Does the film need to employ the ‘storytelling wardrobe’ for a character so at the heart of the story, even when she is female? This presentation examines Cary’s costumes in detail to find out.

Reference

Gaines, Jane. 1991. “Costume and Narrative: How dress tells the woman’s story” in Gaines, Jane and Herzog, Charlotte, eds, Fabrications: Costume and the Female Body. New York and London: Routledge.

Lies Lanckman, University of Kent, Film Studies

“All the melodramatics of my life are past!”: The Fan Magazine as a Melodramatic Medium

Although the topic of maternal melodrama in film has received attention by a number of scholars, the focus appears to lie primarily on the study of particular emblematic films or, more broadly, on maternal melodrama on screen. This paper, however, will explore another connection between (Hollywood) film and melodrama; the way in which not just many films, but also the fan magazine and the star narratives contained within its pages can be seen to include a number of melodramatic elements.

film has received attention by a number of scholars, the focus appears to lie primarily on the study of particular emblematic films or, more broadly, on maternal melodrama on screen. This paper, however, will explore another connection between (Hollywood) film and melodrama; the way in which not just many films, but also the fan magazine and the star narratives contained within its pages can be seen to include a number of melodramatic elements.

By exploring fan magazine rhetoric produced between 1920 and 1940, I highlight a number of key themes and the way their treatment might be called melodramatic, ranging from the characterisation of particular stars, to the treatment of key life experiences, such as love, marriage and death. In this paper, however, I will particularly highlight the treatment of motherhood in the pages of publications such as Photoplay, focusing on two separate case studies. One is the treatment of Norma Shearer’s role as a tragic widow and single mother after the premature death of husband Irving Thalberg in September 1936. The other will focus on the rhetoric surrounding the divorce of Barbara Stanwyck and Frank Fay in December 1935, which cast Stanwyck as an excessive/monstrous mother who essentially emasculated her (less successful) husband. Using these two case studies, I will attempt to draw comparisons between Hollywoodian (maternal) melodrama on and off screen.

as Photoplay, focusing on two separate case studies. One is the treatment of Norma Shearer’s role as a tragic widow and single mother after the premature death of husband Irving Thalberg in September 1936. The other will focus on the rhetoric surrounding the divorce of Barbara Stanwyck and Frank Fay in December 1935, which cast Stanwyck as an excessive/monstrous mother who essentially emasculated her (less successful) husband. Using these two case studies, I will attempt to draw comparisons between Hollywoodian (maternal) melodrama on and off screen.

Ann-Marie Fleming, University of Kent, Film Studies

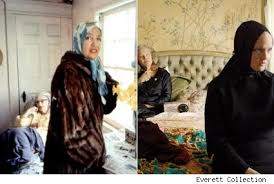

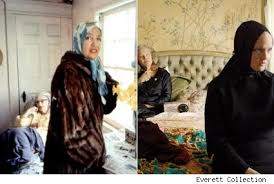

“It’s very difficult to keep the line between the past and the present”: Exploring the melodramatic depictions of the women from Grey Gardens (1975 and 2009).

This paper seeks to explore how we understand mother-daughter tensions and acceptance through the use of the past in both Grey Gardens (1975) and the docudrama of the same name from 2009. Life at  Grey Gardens does not progress; instead the past is the present. Melodramatic moments, particularly the interactions between Edith and Edie, are caused by and centred on past grievances that are as much alive in 1976 as they were in 1952. In contrast, the docudrama’s past is shown as a tool to heighten the pain of the present, whilst stylistically appearing more significant.

Grey Gardens does not progress; instead the past is the present. Melodramatic moments, particularly the interactions between Edith and Edie, are caused by and centred on past grievances that are as much alive in 1976 as they were in 1952. In contrast, the docudrama’s past is shown as a tool to heighten the pain of the present, whilst stylistically appearing more significant.

Primarily the paper will focus on the films’ depiction of:

- The unsaid, said and shown – An examination of the melodrama caused by the discussion of the past in contrast to the performance style of the docudrama.

- Female urgency – The importance of the female body and its dominance of the frame at the peak of the melodramatic performance/reaction.

- The rise and fall of tension – How each form manipulates time and remembrance to create melodramatic sympathy.

- The melodrama of life itself – The re-creation of the past self and the character of the present.

Despite the differences in film form the paper hopes to expose one important factor: familial melodrama arises from the past’s collision with the present.

We hope you’ll be able to join us on the 3rd of June to hear the papers in full!

Update: the event is free, but booking is essential. Please email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to secure your place.