Our discussion of Female ranged from its genre, its use of gender inversion, its star, Ruth Chatterton, comparison to other films and stars of the time such as Barbara Stanwyck in Baby Face, its studio – Warner Brothers – the film’s set and its shot transitions.

We began with debate about the film’s genre. The American Film Institute (AFI) categorises Female as ‘Comedy-drama’ (https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/MovieDetails/3957?cxt=filmography) and we certainly noted its, sometimes uneasy, mix of serious issues such as sexual equality (a major subject according to the AFI) and comedic moments. We particularly commented on the film’s heroine, automobile factory owner and manager Alison Drake (Ruth Chatterton). Alison demonstrates her sexual liberation, and position of authority, by seducing young men in her employ and then arranging for them to be transferred to other parts of the world when they become clingy and troublesome.

We began with debate about the film’s genre. The American Film Institute (AFI) categorises Female as ‘Comedy-drama’ (https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/MovieDetails/3957?cxt=filmography) and we certainly noted its, sometimes uneasy, mix of serious issues such as sexual equality (a major subject according to the AFI) and comedic moments. We particularly commented on the film’s heroine, automobile factory owner and manager Alison Drake (Ruth Chatterton). Alison demonstrates her sexual liberation, and position of authority, by seducing young men in her employ and then arranging for them to be transferred to other parts of the world when they become clingy and troublesome.

Alison is a woman in charge of her own destiny, telling a female friend, Harriet Brown (Lois Wilson), that she uses men the way they have always used women. She is, therefore, very different to the suffering heroine of melodrama. In fact, she seems more like the sexually predatory man a melodrama heroine is often running from.

Alison is frustrated, however, by the fact that despite her viewing herself as a sexual being, the men she attempts to seduce have differing ideas. Men either submit and then fall in love and wish to marry and domesticate her (and are hence transferred to Montreal), or seem resistant to her female charms, considering her to be made of marble, rather than flesh and blood (and are dispatched to Paris). Other marriage proposals she receives are similarly not based on how Alison sees her true self, but are couched in terms of a business merger.

Alison is frustrated, however, by the fact that despite her viewing herself as a sexual being, the men she attempts to seduce have differing ideas. Men either submit and then fall in love and wish to marry and domesticate her (and are hence transferred to Montreal), or seem resistant to her female charms, considering her to be made of marble, rather than flesh and blood (and are dispatched to Paris). Other marriage proposals she receives are similarly not based on how Alison sees her true self, but are couched in terms of a business merger.

The repetitive nature of Alison’s attempted seductions (and indeed her preparedness, in, we presume, providing male guests with bathing costumes for her swimming pool) become comic as the film proceeds. She invites men to her house for the evening; she is clad in a beautiful evening dress; we hear ‘Shanghai Li’ playing; Alison summons a butler, and vodka, at the right moment by pushing a button; Alison earnestly explains that she is not all about business, inviting her male visitor to sit next to her as she playfully throws a cushion on the floor.

The repetitive nature of Alison’s attempted seductions (and indeed her preparedness, in, we presume, providing male guests with bathing costumes for her swimming pool) become comic as the film proceeds. She invites men to her house for the evening; she is clad in a beautiful evening dress; we hear ‘Shanghai Li’ playing; Alison summons a butler, and vodka, at the right moment by pushing a button; Alison earnestly explains that she is not all about business, inviting her male visitor to sit next to her as she playfully throws a cushion on the floor.

The other comedy aspect the film brought to mind was the screwball subgenre. After becoming frustrated at the lack of men who see her as she truly is, Alison leaves her own party, dressing up in casual clothes to visit a local fair. While there, she takes aim with a rifle at the shooting gallery alongside an attractive man, Jim Thorne (George Brent). They alternate successful shots at targets until Alison’s last one misses, and Jim completes the task for her. This is a ‘meet-cute’ of romantic comedy, something which shows that the couple is meant to be together. Alison is, however, the pursuer rather than the pursued (despite the fact the man has won the so obviously male shooting competition) as she follows Jim as he purchases a drink at a nearby stall. Alison light-heartedly assumes an alternative identity as a former sharpshooter, and Jim plays along by saying that he did not recognise her without her horse. Significantly, Alison’s assumed identity is one of much lower class than her real status. This corresponds to some of the key aspects Tamar Jeffers McDonald cites as key to screwball – reverse class snobbery, a major inversion or subversion of characters’ normality, and role play (Romantic Comedy: Boy Meets Girl Meets Genre, 2007, pp. 23-24). It is worth noting, however that while Jim plays along, he does not assume an alternate identity or pretend to be anything he is not.

The other comedy aspect the film brought to mind was the screwball subgenre. After becoming frustrated at the lack of men who see her as she truly is, Alison leaves her own party, dressing up in casual clothes to visit a local fair. While there, she takes aim with a rifle at the shooting gallery alongside an attractive man, Jim Thorne (George Brent). They alternate successful shots at targets until Alison’s last one misses, and Jim completes the task for her. This is a ‘meet-cute’ of romantic comedy, something which shows that the couple is meant to be together. Alison is, however, the pursuer rather than the pursued (despite the fact the man has won the so obviously male shooting competition) as she follows Jim as he purchases a drink at a nearby stall. Alison light-heartedly assumes an alternative identity as a former sharpshooter, and Jim plays along by saying that he did not recognise her without her horse. Significantly, Alison’s assumed identity is one of much lower class than her real status. This corresponds to some of the key aspects Tamar Jeffers McDonald cites as key to screwball – reverse class snobbery, a major inversion or subversion of characters’ normality, and role play (Romantic Comedy: Boy Meets Girl Meets Genre, 2007, pp. 23-24). It is worth noting, however that while Jim plays along, he does not assume an alternate identity or pretend to be anything he is not.

Perhaps predictably, Jim refuses to be ‘picked up’ by Alison, apparently she is ‘too fresh’. There must be some obstacles to their (we suppose) eventual union. Furthermore, he spurns her advances when, coincidentally, he begins work at her company as an important engineer the next day. While her seduction routine has worked with others, Jim seems immune. When Alison is surprised that drinking has not loosened Jim up, he explains that he is used to vodka, after working for some time in Russia. This shows how much she has relied on alcohol in past seductions, and that Alison has to work much harder at her ‘vamping’ than usual.

Perhaps predictably, Jim refuses to be ‘picked up’ by Alison, apparently she is ‘too fresh’. There must be some obstacles to their (we suppose) eventual union. Furthermore, he spurns her advances when, coincidentally, he begins work at her company as an important engineer the next day. While her seduction routine has worked with others, Jim seems immune. When Alison is surprised that drinking has not loosened Jim up, he explains that he is used to vodka, after working for some time in Russia. This shows how much she has relied on alcohol in past seductions, and that Alison has to work much harder at her ‘vamping’ than usual.

This inversion is not only important in terms of how it might comment on comedic conventions. It is also useful when we compare Alison to other characters in the film, and consider what changes in her representation may say about the film’s standpoint on sexual equality.

The main character we compared Alison to was her old schoolfriend Harriet. She unexpectedly visits Alison in her office, and we witness Alison swapping chat on Harriet’s life (her marriage and children) but being so distracted with work matters she gets several details wrong – Harriet’s husband’s name and the gender and number of her children. This indicates Alison’s lack of interest in ‘usual’ womanly concerns. It is also important that since this chat takes place at work, Alison is nonetheless interrupting her work with personal concerns. This may be less true of the way films choose to represent men in their workplaces.

The main character we compared Alison to was her old schoolfriend Harriet. She unexpectedly visits Alison in her office, and we witness Alison swapping chat on Harriet’s life (her marriage and children) but being so distracted with work matters she gets several details wrong – Harriet’s husband’s name and the gender and number of her children. This indicates Alison’s lack of interest in ‘usual’ womanly concerns. It is also important that since this chat takes place at work, Alison is nonetheless interrupting her work with personal concerns. This may be less true of the way films choose to represent men in their workplaces.

We wondered whether the film had the purpose of showing Harriet, rather than Alison, in the more flattering light for both male and female viewers. While the film tones down Alison’s sexually free behaviour as she falls for Jim, though refuses to marry him at first, her enjoyment for most of the film and her wearing of stunning clothes, driving a sports car, and owning of a beautiful house. By contrast, Harriet is only seen in Alison’s environment, wearing smart but regular clothes, and her only interaction with her husband and children is a boring phone call about his health. We thought this did not encourage the promotion of Harriet’s more traditional lifestyle over Alison’s more modern one.

We wondered whether the film had the purpose of showing Harriet, rather than Alison, in the more flattering light for both male and female viewers. While the film tones down Alison’s sexually free behaviour as she falls for Jim, though refuses to marry him at first, her enjoyment for most of the film and her wearing of stunning clothes, driving a sports car, and owning of a beautiful house. By contrast, Harriet is only seen in Alison’s environment, wearing smart but regular clothes, and her only interaction with her husband and children is a boring phone call about his health. We thought this did not encourage the promotion of Harriet’s more traditional lifestyle over Alison’s more modern one.

There is ambivalence though. In addition to times when Alison seems to be displaying herself for men’s attention, Alison is filmed in a rather sexual way at other points of the narrative. She is a powerless sexual object as she steps in and out of the shower, and receives massages.

The film is also ambivalent in its representation of Alison on her own terms. Her initial boast that she treats men the way they have always treated women, is tempered by her last minute conversion to domesticity. Despite Alison tracking down Jim at a shooting gallery and his support of her business plans, she decides to hand over the business to him while she plans to have 9 children. It is well worth considering whether the lasting memory of a film is a character’s behaviour for most of the story, or he final few minutes. Some commented that in this sense the film was two-faced. The ending is a sop to men (with Jim also specifically speaking against ‘free women’), and traditionalists, but others (including women) may choose not to believe Alison’s last exaggerated desire.

The film is also ambivalent in its representation of Alison on her own terms. Her initial boast that she treats men the way they have always treated women, is tempered by her last minute conversion to domesticity. Despite Alison tracking down Jim at a shooting gallery and his support of her business plans, she decides to hand over the business to him while she plans to have 9 children. It is well worth considering whether the lasting memory of a film is a character’s behaviour for most of the story, or he final few minutes. Some commented that in this sense the film was two-faced. The ending is a sop to men (with Jim also specifically speaking against ‘free women’), and traditionalists, but others (including women) may choose not to believe Alison’s last exaggerated desire.

We also briefly mentioned the minor, and older, characters of Pettigrew (Ferdinand Gottschalk) and Miss Frothingham (Ruth Donnelly). They represent more traditional gender politics. While Pettigrew seems to approve of Alison’s treatment of men for most of the narrative, he is also relieved when she decided to settle down. Pettigrew teasingly asks Miss Frothingham if she lives with her ‘folks’ and she giggles in her response that she lives alone. While Miss Frothingham appears aware of Pettigrew’s attentions, and intentions, and both of them flirt, Pettigrew is the more obvious predating figure. He is even unoriginal in asking Miss Frothingham up to his apartment to see his paintings.

We also briefly mentioned the minor, and older, characters of Pettigrew (Ferdinand Gottschalk) and Miss Frothingham (Ruth Donnelly). They represent more traditional gender politics. While Pettigrew seems to approve of Alison’s treatment of men for most of the narrative, he is also relieved when she decided to settle down. Pettigrew teasingly asks Miss Frothingham if she lives with her ‘folks’ and she giggles in her response that she lives alone. While Miss Frothingham appears aware of Pettigrew’s attentions, and intentions, and both of them flirt, Pettigrew is the more obvious predating figure. He is even unoriginal in asking Miss Frothingham up to his apartment to see his paintings.

We also discussed the significance of Ruth Chatterton playing Alison, and whether this colours our view of her character’s liberation as positive or negative. Chatterton was a powerful woman, as in addition to being an actor and star she was an aviatrix, a fencer and owned her own production company. It would be interesting to see how much of this information was available to, and known by, audiences of the time. As Lies points out in her post on the NoRMMA blog, Chatterton’s 1932-1934 marriage to Female co-star George Brent was referenced in a portrait of Chatterton in February 1934’s Photoplay (www.normmanetwork.com/you-wouldnt-have-these-problems-if-you-were-a-fallen-woman-female-curtiz-1933/) This shows Chatterton’s acceptable off-screen domestic situation, but also the fact that she continued to work despite being married.

We also discussed the significance of Ruth Chatterton playing Alison, and whether this colours our view of her character’s liberation as positive or negative. Chatterton was a powerful woman, as in addition to being an actor and star she was an aviatrix, a fencer and owned her own production company. It would be interesting to see how much of this information was available to, and known by, audiences of the time. As Lies points out in her post on the NoRMMA blog, Chatterton’s 1932-1934 marriage to Female co-star George Brent was referenced in a portrait of Chatterton in February 1934’s Photoplay (www.normmanetwork.com/you-wouldnt-have-these-problems-if-you-were-a-fallen-woman-female-curtiz-1933/) This shows Chatterton’s acceptable off-screen domestic situation, but also the fact that she continued to work despite being married.

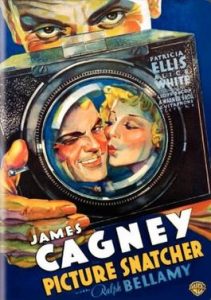

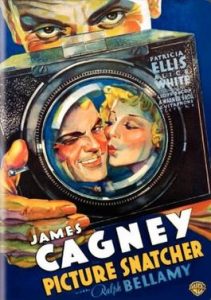

The context of the studio which produced Female was also considered. We were reminded throughout the film of its studio since Warner tunes like ‘You’re Getting to be a Habit with Me’ and ‘Shuffle Off to Buffalo’ (both from 42nd Street, 1933) were hummed or whistled by characters. There was also mention of the Warner Brothers star James Cagney (at the studio from 1930-1935). Alison hires a private detective to follow Jim when she is not being as successful with him as she would like. It is said that he has been out the night before, at a movie called Picture Snatcher (1933, released 6 months before Female). Some of us were also aware of Warner Brothers through costumes being recycled from earlier and into later films from the studio. Unlike the bigger MGM, Warner Brothers was less able to spend lavishly on both costumes and film tunes.

The context of the studio which produced Female was also considered. We were reminded throughout the film of its studio since Warner tunes like ‘You’re Getting to be a Habit with Me’ and ‘Shuffle Off to Buffalo’ (both from 42nd Street, 1933) were hummed or whistled by characters. There was also mention of the Warner Brothers star James Cagney (at the studio from 1930-1935). Alison hires a private detective to follow Jim when she is not being as successful with him as she would like. It is said that he has been out the night before, at a movie called Picture Snatcher (1933, released 6 months before Female). Some of us were also aware of Warner Brothers through costumes being recycled from earlier and into later films from the studio. Unlike the bigger MGM, Warner Brothers was less able to spend lavishly on both costumes and film tunes.

We also considered Female in relation to a screening from last term, Baby Face (see blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2017/12/04/summary-of-discussion-on-baby-face/) Both films were written by Gene Markey and Kathryn Scola. But in addition to being based on a novel by a male author (Donald Henderson Clarke 1932), Female was notably different to Baby Face in the lack of a suffering and abused heroine. Interestingly though, according to Motion Picture, the star of Baby Face, Barbara Stanwyck, was considered for the role before it was toned down and given to Chatterton. (See Lies’ post: www.normmanetwork.com/you-wouldnt-have-these-problems-if-you-were-a-fallen-woman-female-curtiz-1933/) It is interesting to consider what a different film Female would have been if Stanwyck had played Alison. Stanwyck often played struggling everyday characters, with her ‘real’ background also apparently a poor one. Chatterton, meanwhile, was the middle-class daughter of an architect and prior to Hollywood had a successful career on the legitimate stage.

We also considered Female in relation to a screening from last term, Baby Face (see blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2017/12/04/summary-of-discussion-on-baby-face/) Both films were written by Gene Markey and Kathryn Scola. But in addition to being based on a novel by a male author (Donald Henderson Clarke 1932), Female was notably different to Baby Face in the lack of a suffering and abused heroine. Interestingly though, according to Motion Picture, the star of Baby Face, Barbara Stanwyck, was considered for the role before it was toned down and given to Chatterton. (See Lies’ post: www.normmanetwork.com/you-wouldnt-have-these-problems-if-you-were-a-fallen-woman-female-curtiz-1933/) It is interesting to consider what a different film Female would have been if Stanwyck had played Alison. Stanwyck often played struggling everyday characters, with her ‘real’ background also apparently a poor one. Chatterton, meanwhile, was the middle-class daughter of an architect and prior to Hollywood had a successful career on the legitimate stage.

We also commented on the film’s impressive set. According to the AFI, some of this was filmed at the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Ennis house in Los Angeles https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/moviedetails/3957 The house was also apparently used for later films including House on Haunted Hill (1959), The Day of the Locust (1975) and Blade Runner (1982).

We also commented on the film’s impressive set. According to the AFI, some of this was filmed at the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Ennis house in Los Angeles https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/moviedetails/3957 The house was also apparently used for later films including House on Haunted Hill (1959), The Day of the Locust (1975) and Blade Runner (1982).

It was not just the exterior shots of the house or the swimming pool which were striking though. All the characters seemed dwarfed by the size of both the factory and house interiors which further emphasise Alison’s wealth. The way in which the working of the factory (smoking chimneys, cranes etc) are seen through the large window as Alison sits at her desk also comments on her wealth, but also her hard work and the heavy industry involved in the manufacturing the automobiles. It also reveals that Alison sis able to survey all of this from her desk – it is her domain.

It was not just the exterior shots of the house or the swimming pool which were striking though. All the characters seemed dwarfed by the size of both the factory and house interiors which further emphasise Alison’s wealth. The way in which the working of the factory (smoking chimneys, cranes etc) are seen through the large window as Alison sits at her desk also comments on her wealth, but also her hard work and the heavy industry involved in the manufacturing the automobiles. It also reveals that Alison sis able to survey all of this from her desk – it is her domain.

Finally, there was some comment on the film’s editing. Some found the variety of shot transitions, especially on the factory floor, distracting and showy. Others, however, hardly noticed them. We might compare the editing to the film’s use of startling 1920s architecture which makes it seem especially modern

As ever, do log in to comment or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.