There are often occasions when we are presented with information or a situation which gets our hackles rising. A picky complaint, a misplaced rumour, an assumption, a one-off gaffe. We know that the situation does not reflect the general reality (our team doesn’t usually screw things up) but we still get annoyed.

Think about it – we get wound up, we try and button the emotion, perhaps it will annoy us for the next hour, the day, the whole week even. It really defeats us one way or another – and it might only be a trivial thing (although sometimes it can be more than trivial – for example if a senior colleague complains).

What can we do? Chew on it all (and get ourselves down or our blood boiling), stand up for it (and risk being seen to be defensive), roll over and take the negativity (and appear passive and weak)?

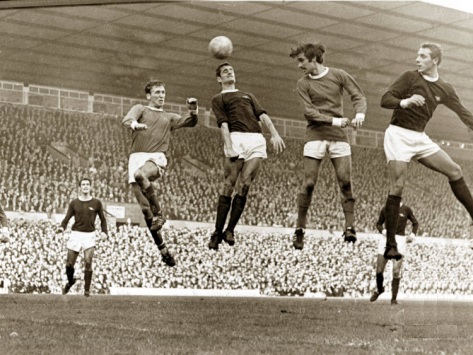

At the 2014 football World Cup we saw the first use of goal line technology – aimed to remove the subjective decision of a referee on whether a ball had crossed the line to indicate a goal. The goal camera’s analytical video was shown on the stadium screens. In the match between France and Honduras a shot by a French player hit the goal post ran back across the goal, rebounded into the goalkeeper and headed towards the goal. Had it crossed the line? The referee indicated goal, then the video replay showed the movement of the ball onto the post and the indication ‘no goal’.

The Honduran players were apoplectic – it was no goal surely! But wait, what had really happened? The video instantly replayed the next sequence – the ball travelling across the goal, hitting the goalkeeper and crossing the line – and the video indicated for this second sequence ‘GOAL’. The referee’s decision was correct (he gets automatic signals only for GOAL).

This is not about goal-line technology.

This issue is that the Honduran team not only had an unjustified emotional reaction, but also their reaction distracted them from their work (football) -they lost 3-0. If they had been rational about it they would have waited for the verdict on the goalkeepers ‘save’ on the goal-line.

The problem we have as human beings is that the emotional centres in our brains operate much more quickly than our rational centres, so we are triggered into an emotional response when a rational response would be better (Peters 2012).

What could be the solution to this? I suggest one. When you are confronted with a difficult situation that you are included to react towards emotionally – seek knowledge (Deming 1982). What do we know, does this always happen, why did they ask this, why did the incident occur, what does data tell us, is it a one off or a repeating occurrence?

Don’t focus on the people, but examine the situation first.

Reading:

Deming W.E. (1982) Out of the Crisis, MIT CAES, Cambridge MA.

Peters S. (2012) The Chimp Paradox: The Mind Management Programme to Help You Achieve Success, Confidence and Happiness. Vermillion, London.

Links:

BBC Sport (2014) World Cup 2014: Goallien technology TV process Reviewed. http://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/0/football/27864393

It is a sporting theme again, inspired by the thrills of the Winter Olympics. Let’s hark back to the 1988 Calgary Games, memorable since British involvement started to impress outside the ice-rink. Eccentricities of Eddie ‘the Eagle’ Edwards, our first Olympic ski-jumper matched Martin Bell’s efforts in the men’s downhill. Even our bob-sledders were competitive.

It is a sporting theme again, inspired by the thrills of the Winter Olympics. Let’s hark back to the 1988 Calgary Games, memorable since British involvement started to impress outside the ice-rink. Eccentricities of Eddie ‘the Eagle’ Edwards, our first Olympic ski-jumper matched Martin Bell’s efforts in the men’s downhill. Even our bob-sledders were competitive.