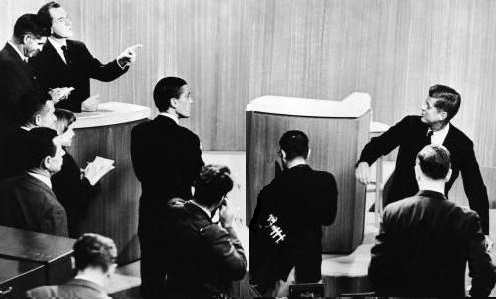

Dealing with change usually involves debate: what to change, why, where, when, how and who?

Dealing with change usually involves debate: what to change, why, where, when, how and who?

There is often the danger that skeptical inquiry can creep towards defensiveness and cynicism. Here are some things to challenge when these attributes appear in negative arguments presented by others (adapted from Paine 2013):

POOR responses in discussions include:

- Attacking the person not the argument, or stereotyping a position to make attacks easier.

- Relying on ‘authority’. Hierarchy should make no difference, one person’s opinion should be no weightier than another’s (both are, after all, just opinions) – what are the facts?

- Observational selection (counting positives and forgetting the negatives, or vice versa).

● Statistics of small numbers

(such as drawing conclusions from inadequate sample sizes)

● the ‘sample of one’: using a single case which could be an extreme outlier rather than the norm - ‘conveniently’ considering only two extremes to make the opposing view look worse:

● Excluding the middle options in a range of possibilities

● Short-term v long-term: “why pursue research when we have so huge a budget deficit?”.

● Slippery slope – unwarranted extrapolation “give an inch and they will take a mile” – would they…always? - Misunderstanding the nature of statistics

- Confuse correlation & causation (cause & effect):

‘it happened after so it was caused by’ – is this really justified? - Appeal to ignorance

(but – absence of evidence is not evidence of absence).

To address these arguments ask: what is the purpose of the discussion? what do we know? what are the facts? what are we assuming? what knowledge can we reasonably base our decision making upon? how can we examine, predict and monitor outcomes?

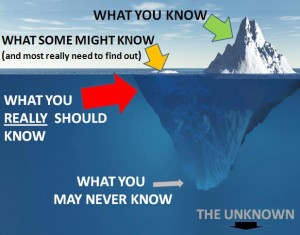

As Deming says, most of what is important is unknown or unknowable, but we don’t assume that it doesn’t exist.

Bring the skeptics into the argument, involve their questions in the testing and development of ideas. Make resistance useful.

Further reading:

Deming W.E. (1982) Out of the Crisis, MIT CAES, Cambridge MA.

Deming W.E. (1993) The New Economics, MIT CAES, Cambridge MA.

Herrero, L. (2006) Viral Change, meetingminds, UK.

Paine M. (2013) Baloney Detection Kit prepared excerpt from The Planetary Society Australian Volunteer Coordinators http://www.carlsagan.com/index_ideascontent.htm#baloney