The term ‘learning organisation’ first gained popularity in the 1990s and is, unusually in the faddish world of ‘management-speak’, one which seems to have endured. What is a ‘learning organisation’ and why try to become one?

The term ‘learning organisation’ first gained popularity in the 1990s and is, unusually in the faddish world of ‘management-speak’, one which seems to have endured. What is a ‘learning organisation’ and why try to become one?

An organisation that learns is best able to adapt. It finds out what works and what doesn’t and, most importantly, does something with that knowledge.

However, a learning organisation doesn’t just accrue information. Some organisations appear to be addicted to data – searching for the ‘facts’ before decisions can be made. This is NOT a characteristic of a learning organisation since it will cause one of two problems (or both): either the organisation will boil itself to death in trivia and noise and not pick up the important signals; or statically churn data without adapting – paralysis by analysis. This is not learning.

A definitive feature about learning is that it involves proactively seeking out knowledge; to make good judgements based on insight. If we want people in our team, department or organisation to start learning, then we should steer them towards good judgements based on insights from analysis. The statement ‘costs are out of control’ is an opinion. However, if we define costs and out of control, we can then test that hypothesis and progress in our understanding (Scholtes 1998). This requires new disciplines of thought. For Deming, part of this transformation is about getting managers to see themselves as experimenters who lead learning.

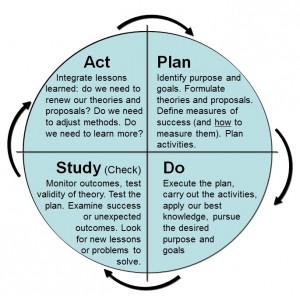

A good way to represent this type of approach is the Deming Wheel (or Shewhart Cycle, as Deming labelled it) Plan-Do-Study-Act; the never-ending cycle of learning (Scholtes 1998). Deming called for a change from ‘opinions’ to hypotheses which we can test, understand and then apply to our work activities.

Scholtes explains the phases of learning. ‘Plan’ and ‘Act’ are the stages of developing and reviewing theories and hypotheses. ‘Do’ and ‘Study’ are about application – work and the examination of work and outcomes. The phases of thinking and doing are intrinsically linked.

“There is nothing as practical as a good theory”

Kurt Lewin

Further Reading:

Drejer, A. (2000)”Organisational learning and competence development”, The Learning Organization, Vol. 7 Iss: 4 pp. 206 – 220

Scholtes, P. R. (1998) The Leader’s Handbook: A guide to inspiring your people and managing the daily workflow, New York: McGraw-Hill

Senge P. (1990) The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organisation, Doubleday, New York.

Other references:

Lewin, K. (1952) Field Theory in Social Science: Selected Theoretical Papers, p. 346. London: Tavistock.

My son and I have been monitoring the frogspawn in our garden pond since April. It has been fascinating to see the tadpoles hatch, then grow into monstrous alien-looking aquatic denizens. Suddenly in the last couple of weeks they have started sprouting limbs, then their feet and toes have lengthened becoming mobile. Body shapes change, the tails shorten and a new form develops.

My son and I have been monitoring the frogspawn in our garden pond since April. It has been fascinating to see the tadpoles hatch, then grow into monstrous alien-looking aquatic denizens. Suddenly in the last couple of weeks they have started sprouting limbs, then their feet and toes have lengthened becoming mobile. Body shapes change, the tails shorten and a new form develops.