The emerging consensus in discussions about leadership and management behaviour in recent decades has focused on ‘changing the way that you lead’.

The emerging consensus in discussions about leadership and management behaviour in recent decades has focused on ‘changing the way that you lead’.

Although the ‘how’ you do it and ‘what’ you do both contribute to effective leadership, the research literature is overwhelmingly focused on the how (Kaiser et al, 2012). Hunt (1991) reviewed the body of published scholarly articles on leadership and estimated that 90% of them were focused on interpersonal processes. It is also most likely that the majority of leadership developers and consultants have a ‘how’ bias, which may influence the debate. The focus is on how you go about things.

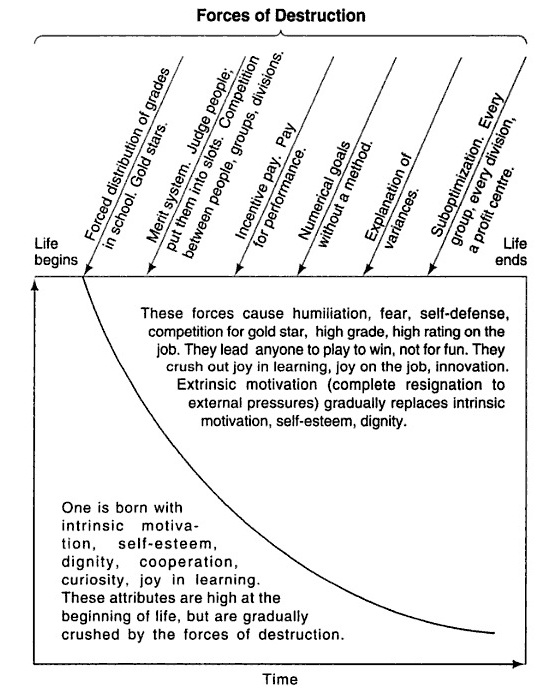

But do leaders know ‘what’ to do? Should we agree aims, develop a vision, inspire people, create teams, empower, engage, delegate, set targets, punish, reward, restructure, enable, measure results, improve services, prioritise, plan or problem-solve? What do these things mean? Which are helpful and which just cause problems?

Of course, HOW we think about these things is important. What is the logic behind reward, recognition or blame? Is it sound logic, or convenient logic, or unfounded assumption, or testable theory (if you are into that). Do we really know what we are doing and assuming? These things must be tested in our own minds, or else we are doing little more than sleepwalking. But the outcome from this thinking must start with what needs to be done. Otherwise we will focus on the hows e.g. (doing it nicely or respectfully or considerately) and end up doing the “wrong things righter”!

Let’s be clear, of course, there is never any excuse for ‘doing the wrong things wronger’, and little benefit in ‘doing the right things wrong’. So this doesn’t let bad management off the hook. Instead, getting our own thinking right (‘what’) is an important start point because it drives better consideration of ‘how’ to go about our business.

Our own styles and preferences (hows) are different to the preferences of each member of our team. We need to be able to adapt in order to interrelate with others effectively. Whilst positive interactions with people are sometimes the icing on the cake, the cake itself must be always be sound. Remember – if we don’t get the ‘whats’ right we will only be deluding ourselves.

Hunt, J. G. (1991). Leadership: A new synthesis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Kaiser, R. B., McGinnis, J. L., & Overfield, D. V. (2012). The how and the what of leadership. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 64(2), 119.

Seddon, J. (2003). Freedom from Command and Control. Buckingham: Vanguard Press.

Here is an interesting one – Researchers at Erasmus University and Cambridge University identified that middle managers copy their boss’s behaviour if they are working in close/adjacent proximity to that boss. Conversely, if the boss is not in close proximity (e.g. has an office down the corridor), then the middle manager may behave differently to the boss.This includes good and bad behaviour.

Here is an interesting one – Researchers at Erasmus University and Cambridge University identified that middle managers copy their boss’s behaviour if they are working in close/adjacent proximity to that boss. Conversely, if the boss is not in close proximity (e.g. has an office down the corridor), then the middle manager may behave differently to the boss.This includes good and bad behaviour.