This blog post forms part of a series exploring identity, culture and heritage as part of the University of Kent’s South Asian Heritage Week.

By Becky Lamyman, Student EDI Officer, Student Services

White British or Mixed Race?

I’m staring at the question that I never know how to answer. It is a standard question, a simple tick box and one that the vast majority of people would answer without a second thought. It simply asks me to define my ethnic origin for data management purposes.

The problem is, I never know whether to tick White British or Mixed. I fluctuate between the two depending on my mood, how much of time I have spent with my family, recent interactions and sometimes it just depends on what day of the week it is. I know that for many mixed race people, particularly second and third generation who have been born and raised in Britain, it is a question of identity that they can struggle with.

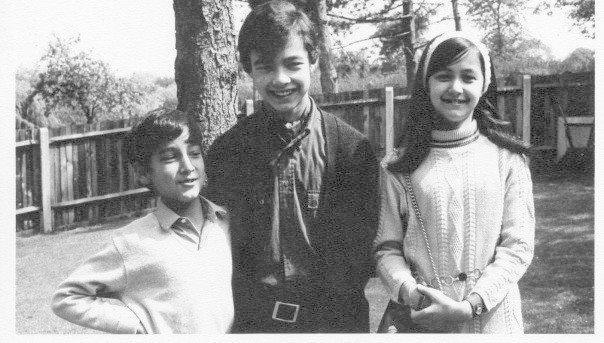

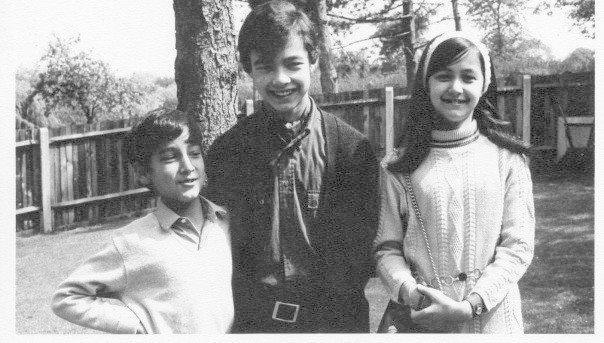

L- R My Uncle Neil, my Uncle Mark and my mother, Kim in their backgarden in England, circa 1970.

For all intents and purposes I am white. I look white. I have tan skin, light eyes and brown hair. Culturally, I would say I am about 90% white. I was born and raised in Britain and would classify myself as British first and foremost. My sister looks much more mixed race than I do. My younger cousins are quite clearly mixed race with tan skin, dark eyes and Asian features. Their older sister is as blonde haired and blue eyed as you can get. Put us all together in a room and you would be forgiven for being confused as to which ones of us were siblings.

L-R, Me, my cousin Emma, my sister Lottie, my cousin Jamie and my cousin Joanna in their backgarden, circa 1998.

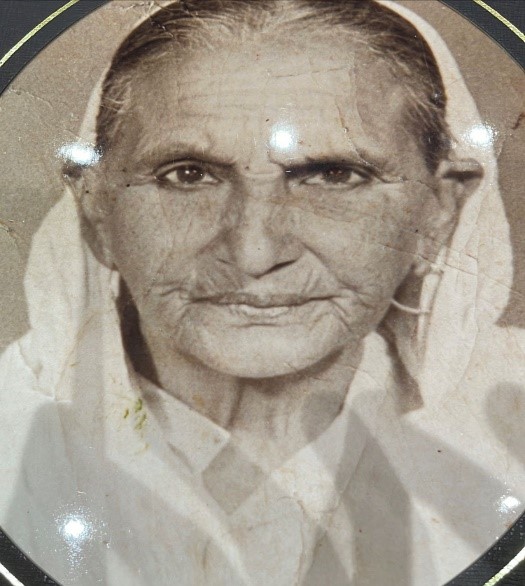

My grandmother is Burmese*. She came to England in 1956 with her husband (an architect born and raised in North London who worked in Burma for a number of years) and her oldest son. She had two more children after they settled in South East London; my mother and my youngest uncle.

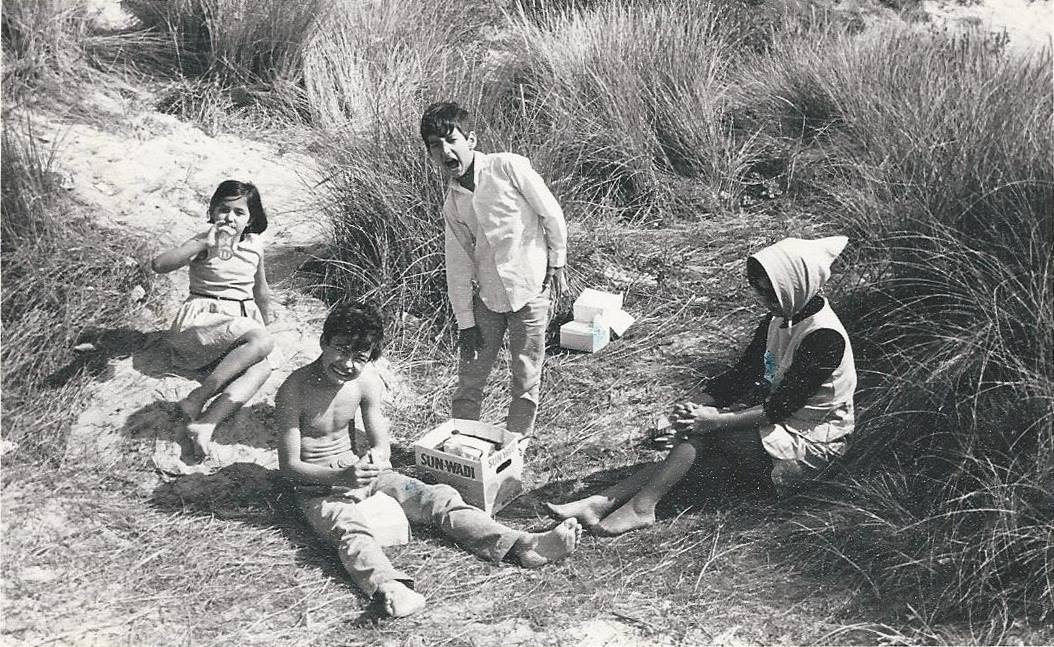

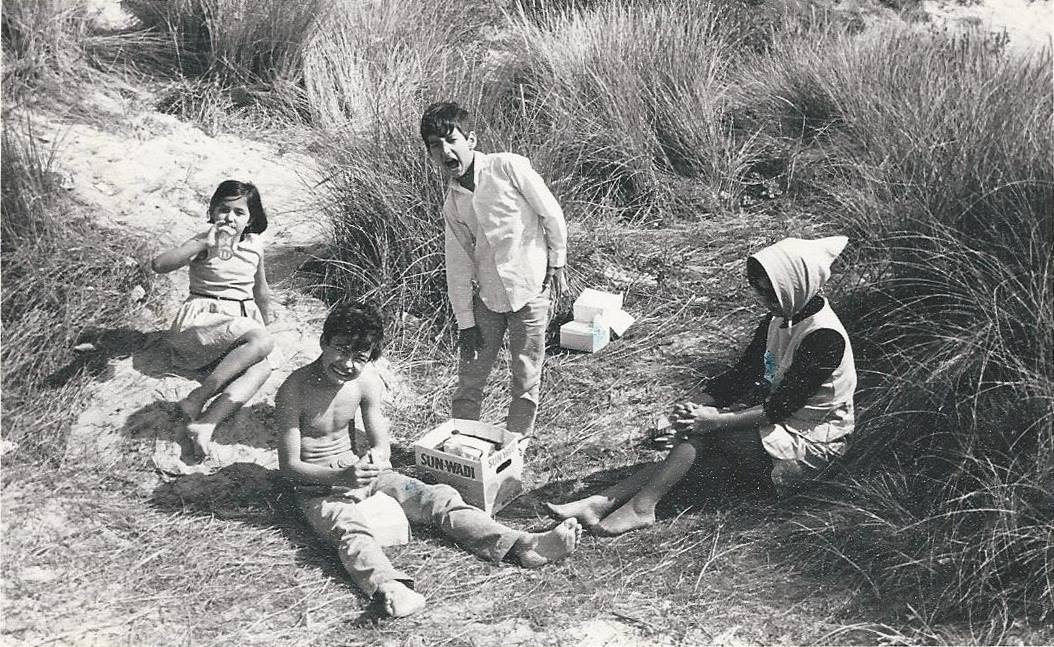

L-R My mother, my grandfather, my Uncle Neil, my grandmother and my Uncle Mark on holiday, circa 1963

My grandmother assimilated quickly. She already spoke fluent, clipped English, was a trained, very bolshy, accountant, had long before stopped wearing her longhi in favour of short skirts and cigarette pants and was (and still is) a devout Catholic. She would however be frustrated for a long time by the lack of mangoes available in supermarkets and her joy when she could finally get her hands on some gulab jaman and balachang was palpable. Believe me, the smell of balachang on toast first thing in the morning is more effective at waking you up than an ice cold shower and my mother loves the vile stuff.

L-R my mother, my Uncle Mark, My Uncle Neil, my grandmother, Camber Sands, circa 1967.

My upbringing was very western. I was raised Catholic, went to a Catholic school, ate a roast dinner every Sunday and have very western ideals and beliefs. I have always been proud of the fact that I am a quarter Burmese though. Grandma insisted we call her ahpwa for a long time and would tell us stories of her childhood in Burma whilst bringing us bags full of mangoes ‘in case they ran out’. She lived an exceptionally privileged lifestyle. Her family were well off and she and her siblings all were given western first names (Joan, Patrick and Joyce).

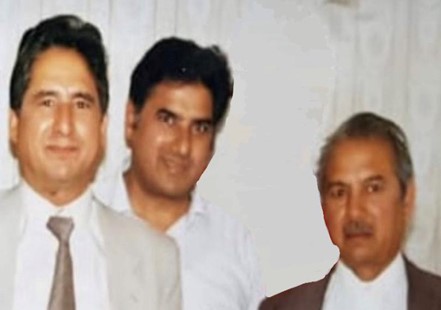

My Great-Uncle Patrick, circa 1998 (my grandmother’s brother)

Having traditionally ‘British identifiers was seen as a mark of wealth and privilege, so she would tell me stories about the red double decker bus she had in the back garden as a ‘playhouse’ and the red phone booth as a ‘garden ornament’. They had cooks, cleaners and gardeners and lived in luxury until the arrival of the Second World War. After that, everything changed and she would tell me stories of foraging for mushrooms for dinner, sometimes helped by the Japanese soldiers whom she said were always very kind to the children they met. She also told me folk stories and I wish I could remember the details of them now as I can’t find them in any folktale book. The one that stands out to me was about the little boy who rescued a dying dragon by feeding him oranges. She would tell me to look at statues of dragons; they still have a small ball resting in their claw in remembrance of his kindness. I have a feeling she made most of this up as I can find no other reference to the myth, but I have always loved the idea.

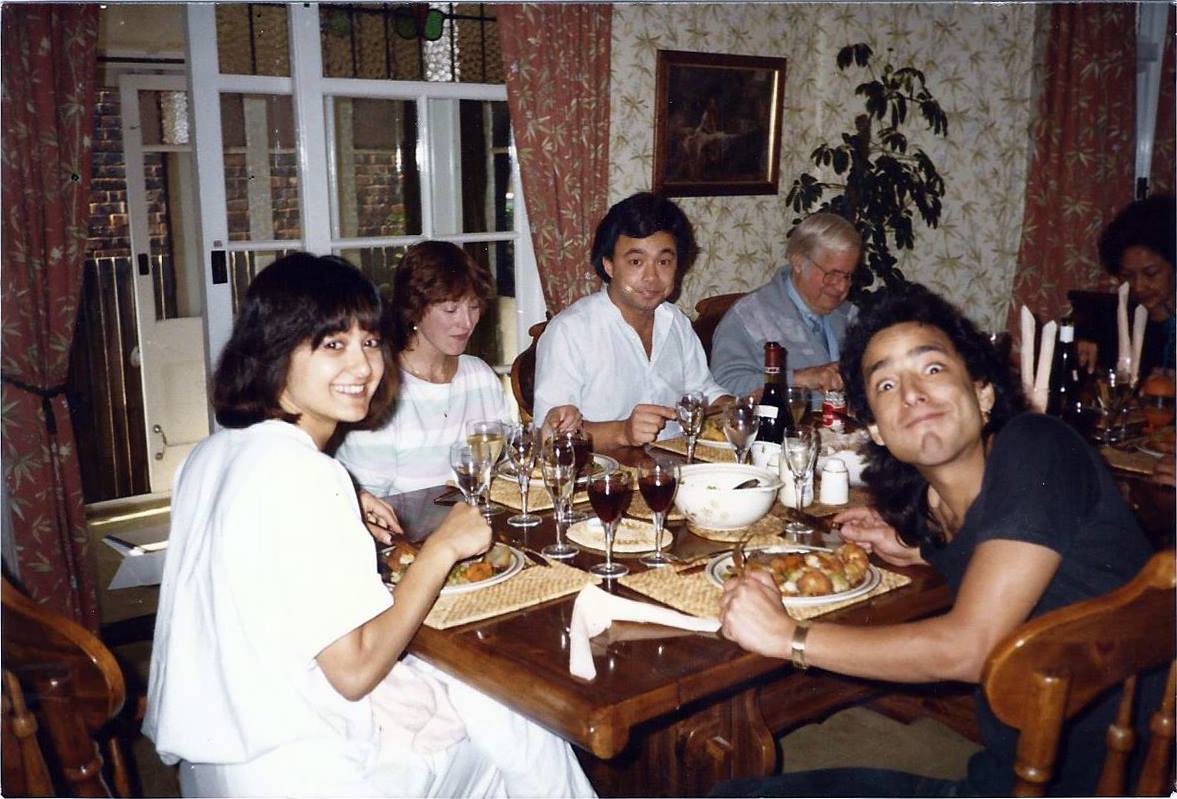

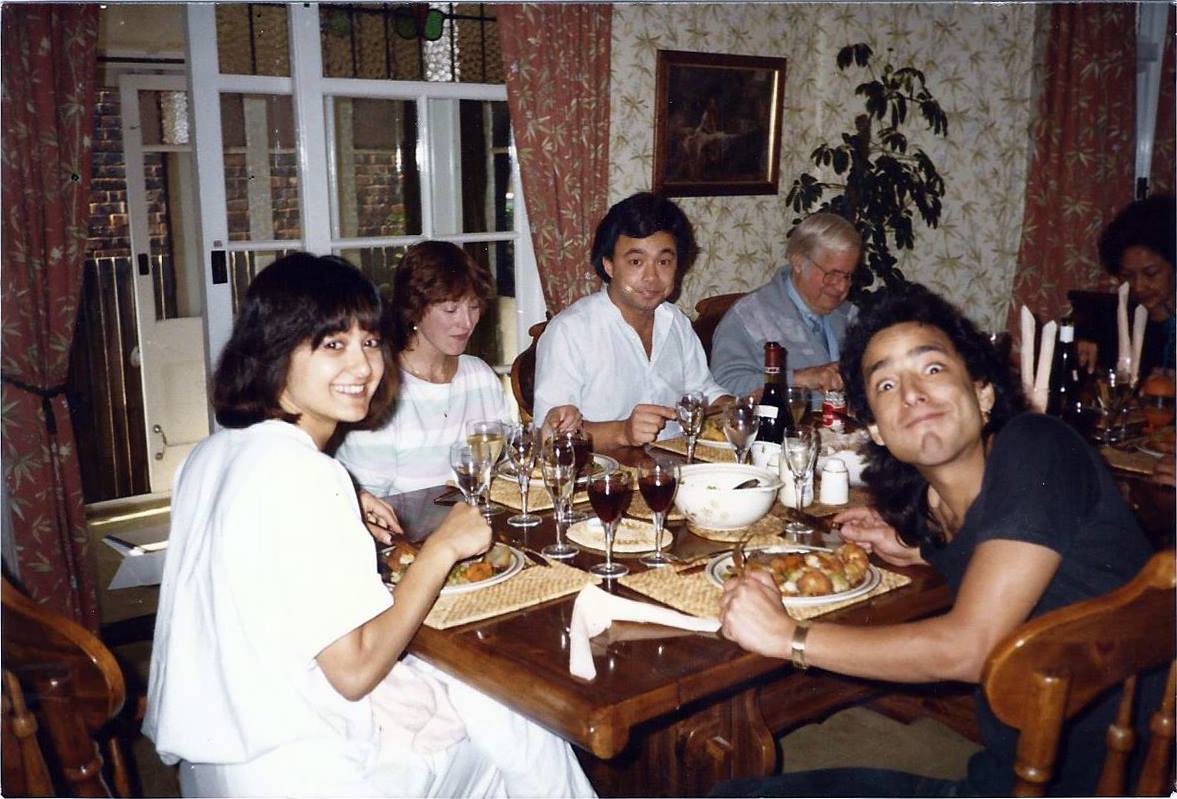

L-R My mother, my Aunt Helena, my Uncle Mark, (unknown friend of my Grandmothers’), my Grandmother, my Uncle Neil. Sunday lunch at my house, circa 1987.

I remember listening to her and my ‘auntie’ Ruth (her best friend) reminisce over the fashion shows in Rangoon they went to as young women and the beauty competitions they entered. Ruth was always very dry and deprecating about them. My grandmother was still sore about the fact that Ruth won Miss Rangoon** instead of her.

My grandmother, aged about 19 in Rangoon, in traditional Burmese wedding attire. This was for a fashion show.

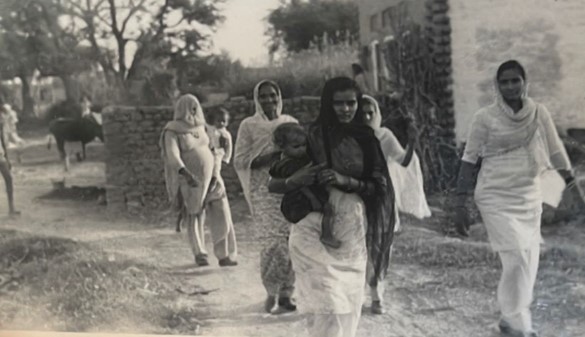

In the years following the war the family scattered. Half went to Australia and the others, along with some of their friends, came to Britain. I don’t know much about those early years. My mother doesn’t talk about it much, but I do know that they experienced undercurrents of racism throughout the late 50s, 60s and 70s. I still remember being about 8 years old, with my mother and younger sister in the supermarket and witnessing an exceptionally nasty altercation. My grandmother is not unbiased herself and had her own very strong, quite unpleasant racist prejudices that still manifest themselves to this day.

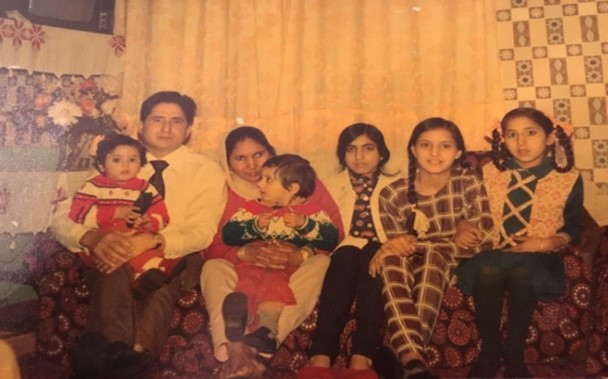

My parent’s wedding party in 1980. L-R my Uncle Fred and Aunt Yvonne (dad’s sister), Grandad Ray (dad’s dad), my grandmother Joan, my dad Rob, my mum Kim, my cousin Joanne, my Nan Nora (dad’s mum), my Grandad Roy (mum’s dad), my Uncle Mark, my Uncle Neil and my Uncle Terry (dad’s brother).

I feel connected, but at the same time strangely disconnected from my heritage. Our house growing up had a mixture of east and west influences. There was a lot of art and furniture bought over by my grandmother from Burma and Thailand. I have been ‘in training’ to develop my tolerance of spice since I was six. My favourite meal is a lamb biriyani (cooked by my mother, but it has to be made with left over roast lamb from the Sunday lunch). My mother used to send me to school with two flasks of it for lunch. One for me, and one for all my friends so that I could actually get a chance to eat mine. I had a scattering of Burmese words, all sadly now lost to time and memory.

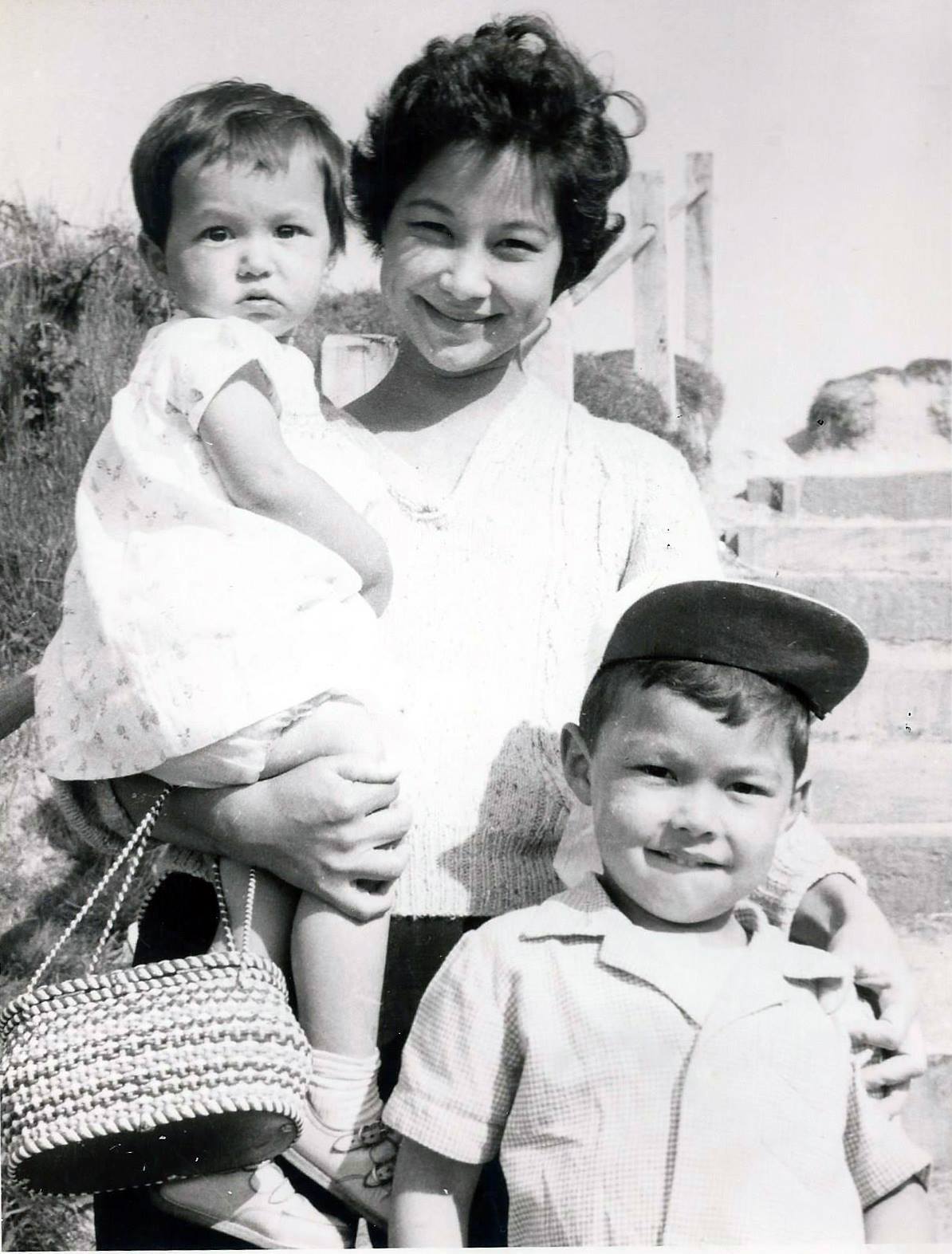

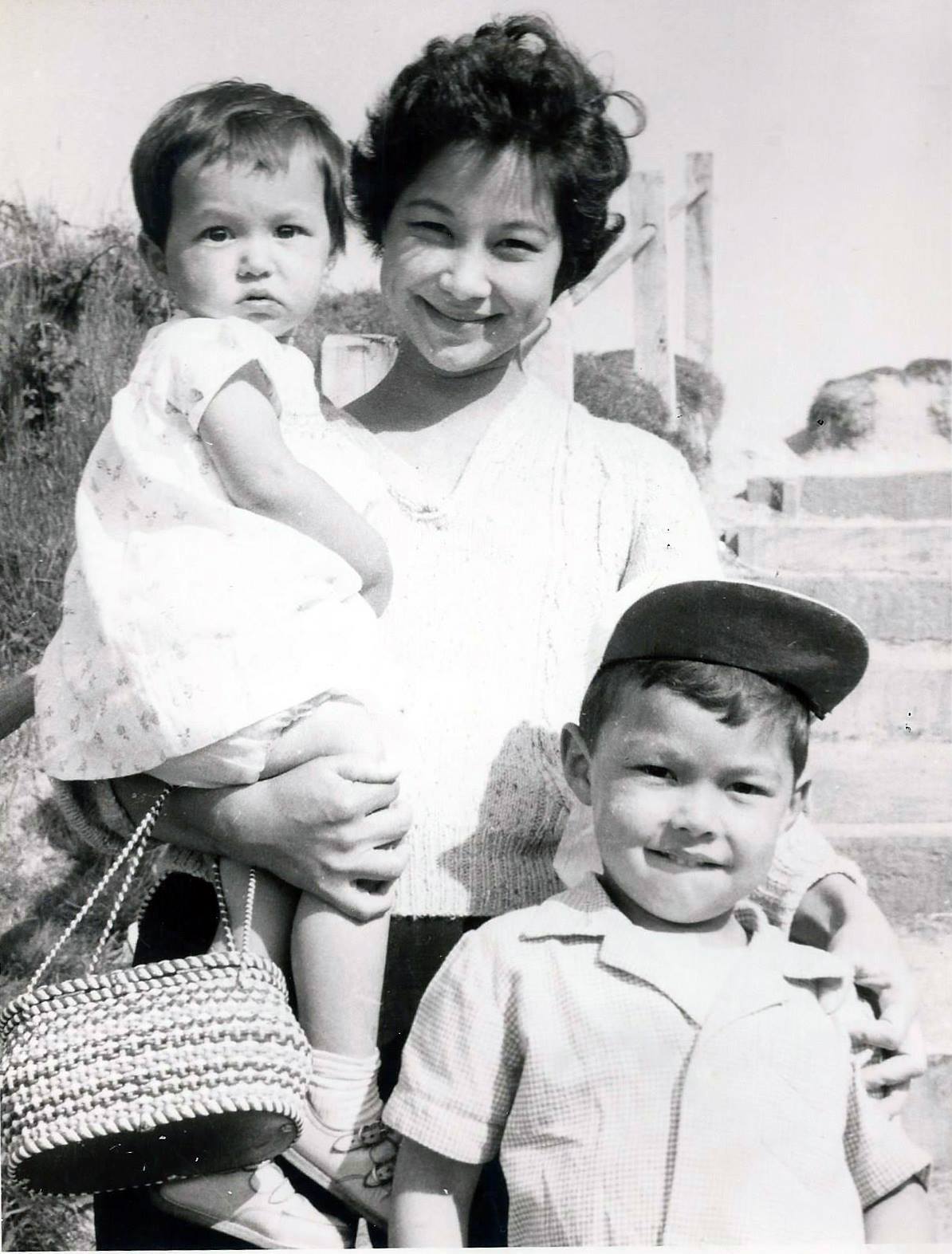

L-R my mother, my grandmother and my Uncle Mark, circa 1958.

My mother went to Burma for the first time for her 60th birthday to fulfil a long held dream. She sent me pictures of the boat ride down the Irrawaddy, the puppet show in the restaurant and my grandmother’s birth house in Rangoon. There is a shop on the lower floor now. I know she feels the same sense of being torn between her identities but to a much stronger degree than I do.

My grandmother with my daughters at her house, Christmas 2021.

I have my own children now, and to see my grandmother with my daughters is both wonderful, but also strangely discombobulating. You would find it hard to tell they were related if I didn’t tell you. Nevertheless, I want to ensure they know where they come from and appreciate the richness of their inheritance. It is this blend of identities, the pulls to my grandmother’s heritage coupled with my own western upbringing and identity that makes the issue of finding the right tick box far more onerous than it has any right to be.

*Burma is now known as Myanmar but my grandmother only ever refers to it as Burma and herself as Burmese so that is what I use.

**Otherwise known as Yangon

This blog post forms part of a series exploring identity, culture and heritage as part of the University of Kent’s South Asian Heritage Week. This week runs from the 28 March -1 April 2022 and invites exploration of the identities, history and heritage of British South Asians.

For more events and activities please see Kent Union’s South Asian Heritage Week website.