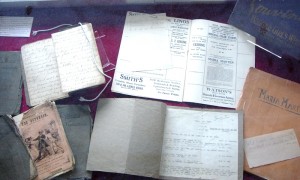

While getting out materials for researchers interested in pantomime and melodrama, I came across an interesting note, penned by Andrew Melville III while drafting his unpublished MS;

Today people look to the front-page of a newspaper for their melodrama

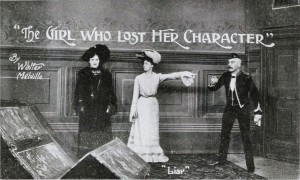

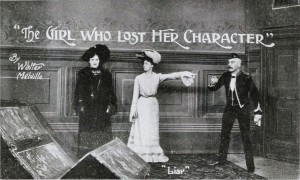

Publicity postcard for the Melvilles' The Girl Who Lost Her Character

I was intrigued by this opinion, suggesting that we still need that touch of the dramatic in our lives, even if melodrama is generally seen (within the theatrical industry as well, I believe) as second rate, over-acted and a generally primitive form of drama. When I started to think about it, though, I began to see what Andrew III meant.

After all, many newspapers and magazines rely on that sense of the over-dramatic to outdo one another and sell as many copies as possible.

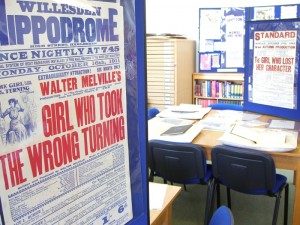

There was fierce competition during the time of the Melvilles’ ownership of several London and provincial theatres, but this was not specifically from rival melodramas, nor from television or radio, but from music hall. ‘It is no good charging 6d when the opposition (possibly a Music Hall) can afford to do it for 2d’ Walter Melville explained in the September 1905 edition of Stageland (0600336). Despite this time of increasing competition for all forms of entertainment, especially before the time of any government subsidy, the Melville family were successful in their acting, writing and management of a number of theatres in London and the provinces. Perhaps the most spectacular success of the family was the partnership between Frederick and Walter Melville, who jointly ran the Lyceum, the Prince’s Theatre and other major theatres, mainly in London. Their melodramas, most notably the ‘Bad Women Dramas’, filled the Melville theatres after the pantomime season, continuing a long theatrical tradition well into the twentieth century.

Fred & Walter

This pair come across as a larger than life duo, with their entire lives revolving around the theatre. Walter was the senior, eldest son of Andrew Melville (I) and his wife Alice, born in 1875, with Frederick the next eldest son, born in 1877. There was a degree of seniority in Walter’s relationship with his brother; according to Andrew III, Walter tried to dominate his brother, but they were ‘twin spirits’ and their success was the result of their ‘mutual endeavour’ (Melville, 0599809/23). The considerable size of their fortunes at the time of their death is testament to their success, but the relationship was fairly tempestuous. From 1921, the brothers were embroiled in a dispute with one another which spilled into a legal quarrel, with both posting notices to announce that the disagreement would force them to shut down the Lyceum at the close of the pantomime. On the last night of the pantomime, February 18th 1922, one of the stars called the brothers on stage, with the news that they were reconciled (0599809/9). The pair shook hands and appeared amicable; however, it is far from clear that they knew anything about this reconciliation before they set foot on the stage. They also had short shrift for any other person who they disapproved of. Walter recounts a trip to a ‘second rate Provincial theatre conducted by my young brother’, most likely Andrew II, who amassed a fortune of his own. The attitude of the eldest son to his siblings gives us some clues into the working and personal relationships of the Melville family.

Eccentricity

Walter Melville

There was certainly a degree of eccentricity about the elder Melville brothers. Andrew III recalls his uncle Walter’s constant aura of theatricality, describing his ‘luxuriant’ overcoat and painstaking dress, including a wide brimmed black hat (599809/23). Walter himself recounts his father’s lessons in the ‘Dignity of the Theatre’, which ensured that he always wore his dark, ‘dress clothes’. Apparently the comedian Fred Leslie thought that Walter ‘was the funiest thing he had ever seen’, at which Walter commented ‘I cannot remember what there was particularly funny in my attire’ (599887/5). In contrast, Fred Melville was described in an obituary as having ‘cared nothing about dress’ (Daily Telegraph, 6 April 1938); he ‘rarely wore a coat to match his trousers or a waistcoat that went with either…wore low Byronic collars and frequently dispensed with a tie’ (599997/6). Fred was also had a ‘fanatical passion for physical fitness’ (599997/6), and a fear of draughts;

‘At panto rehearsals he would erect a shelter in the stalls from odds and ends of scenery, then stand outside it complaining of the cold, enveloped in two heavy overcoats, his trousers tucked into his socks’ (599809/9)

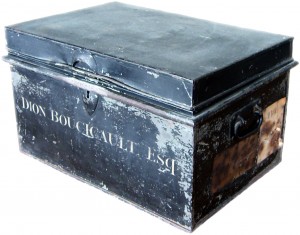

In contrast to Walter, who ‘never knew to what limit a practical joke should go’ (which cost him numerous friends), Andrew III recalls Fred’s ‘shrewdness with considerable wit and humour’ (599997/5). This is aptly illustrated in Fred’s speech Are Authors Cribbers? (0599809/12) which appears to have been written in connection with a legal case for copyright. In it, he states that authors are often the opposite of their heroes, perhaps referring to his own melodramatic plays, and that all known plots are to be found in the Bible, from which playwrights may copy if they choose. The case of Dion Boucicault, himself frequently bound up in litigation relating to copyright, is used as an illustration, and Fred goes on to recount his father’s anger at an unlicensed production of one of his own plays in America. Rather than pursue an expensive legal case, Andrew I put on three of the offending manager’s plays, unliscenced, in revenge. Fred’s own theatrical nature is revealed in the conclusion of his rousing defence. After relating a complaint he received from the famous Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, on the grounds that the Melvilles had stolen a scene from one of his plays, Fred wrote:

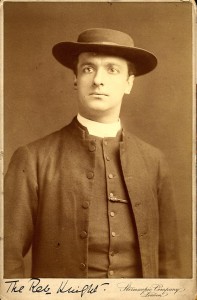

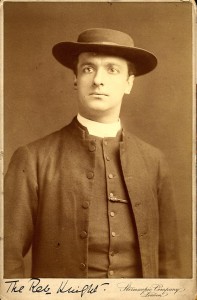

Frederick Melville as Reverend Knight

I was astounded – I had been accused of copying the French from the actual words. I am no cribber. As there had obviously been some mistake, what was I to do because I was certainly not going to submit to the terms of the letter. Just what I did is shown in a letter to Tree saying – “My sketch is taken from my play – A World of Sin – which was produced in 1890. Will you give me the date of the production of your play, because this is of great importance and if you find my play was produced earlier than the French play, you owe me an apology.”

There was no reply.

Oh Herbert, why did you not reply? Oh, Herbert!

The effect of this oration was no doubt similar to the popular reactions to the brothers’ plays.

Fred and Walter ran the Lyceum from 1910-1938, when they leased it to various managers. Andrew Melville III writes ‘in those days, Walter smoked a pipe and drank tea…until about 1910…he forsook the pipe for cigars and the tea for champagne’ (599809/23). This was hardly surprising, given the success of the partnership, but the Melvilles were always more concerned about business than celebrity. Walter’s motto was ‘give the public what they want’ (Stageland, September 1905), while at Fred’s last appearance in public, at the closing of Beauty and the Beast at the Lyceum in 1938, he expounded the principle of pleasing ‘the child that is in us all’ (599997/2). These principles and the brothers’ loyalty and commitment to their work and their employees, ensured that they were remembered with their brother Andrew II as the ‘three musketeers of melodrama’.

Reading the typescript reminiscences of Walter and Fred, including a humourous incident relating to weapons on stage, their theatrical and perhaps even melodramatic personalities spring from the page. Andrew III relates ‘it cannot be said that the Melvilles possessed the ‘charm of the Terrys’ or the ‘social standing of Irving” (599807/10), yet the three brothers, who died within a year of each other, were described as belonging ‘to one of the oldest theatrical families in London and the provinces’. One of Fred’s obituaries adds the accolade that Meville dramas had been played all over the world and acted in many languages. Perhaps there is more truth than eccentricity or melodrama in the plaque beneath the bust of Walter Melville which used to sit in the foyer of the Standard Theatre, Shoreditch:

There is Only One Shakespeare and the is Only One Walter Melville.