When I was little, the favourite present I ever received, was a pretty pink diary, complete with lock and miniature key. Since this key doubled as a pendant one can easily see how such a gift appealed to my vanity. Nowadays, all my secret thoughts are worn on my sleeve; my diary just a scrapbook of places I’ve been. But the point of my rhyme is the lesson this taught me: that books are revered, treasured, and possessed materially.

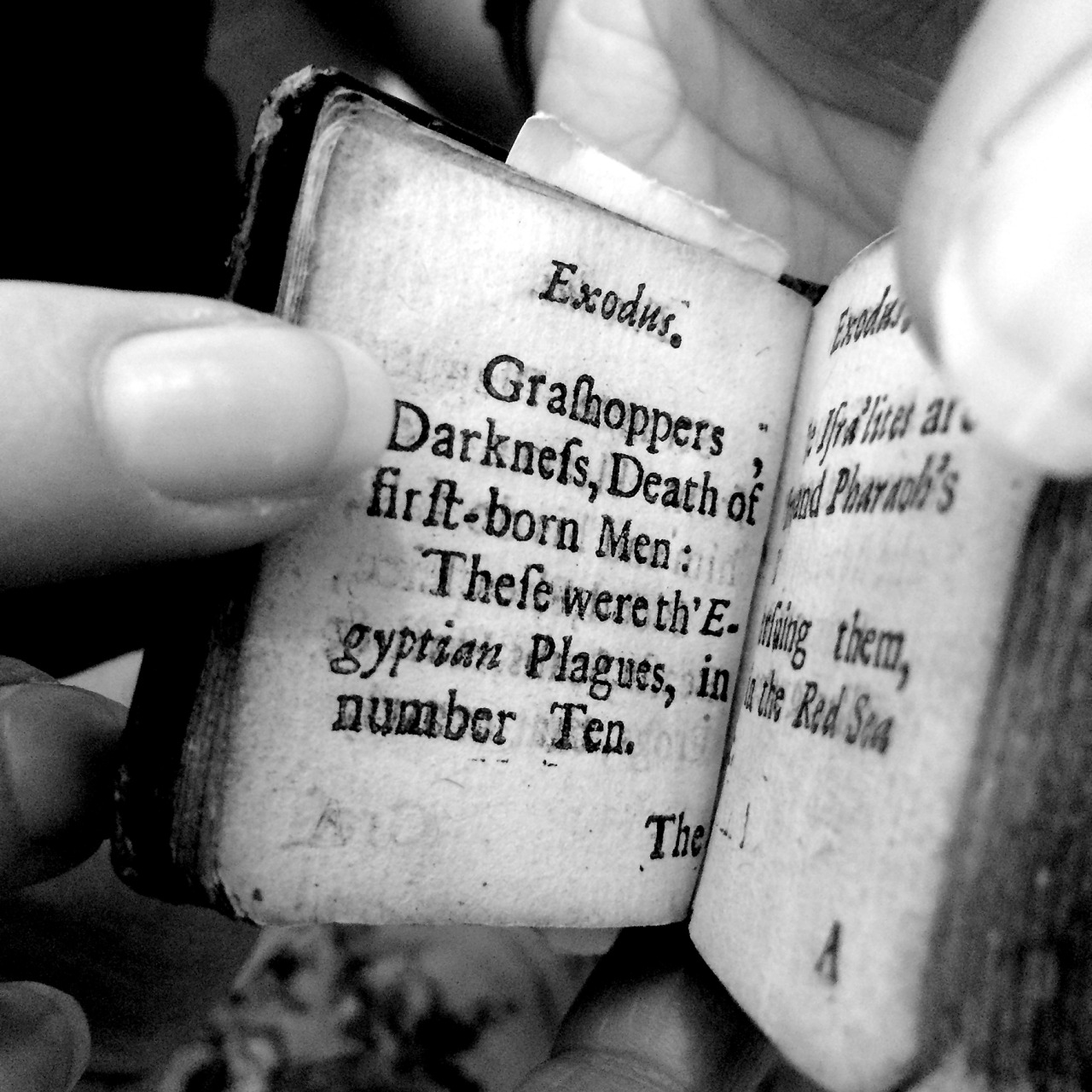

It is undoubtedly a privilege to conduct outreach with Special Collections, and of course this requires transportation of items and their weight alone makes one appreciate the physicality of the book anew. Thus, when we showcase our Pre-1700 folios, we draw attention to the scale of the book as a status symbol as well as an indicator of early modern print technologies. Of course, the miniature book can be as fascinating as the grandest of tomes, as – for instance – our much-loved tiny rhyming bible, Verbum sempiternum, abridged in couplets by the Water Poet, John Taylor. Whilst we can’t possibly know for certain, I like to conjecture how this well-thumbed book could have been intended for daily meditative use, to be carried on one’s person at all times. Certainly, the biblical text is followed by prayers for morning and evening as if to suggest the applicability of reading it over the course of one day.

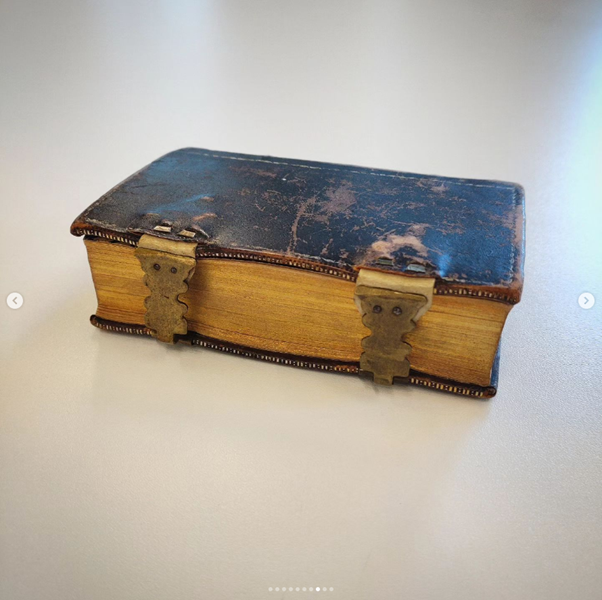

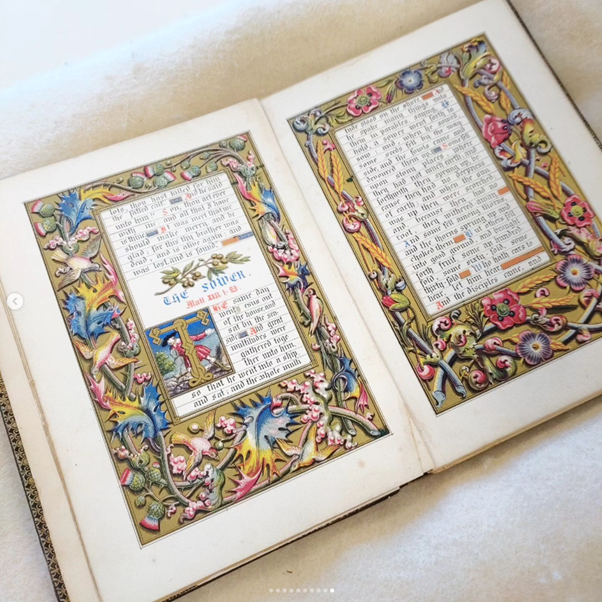

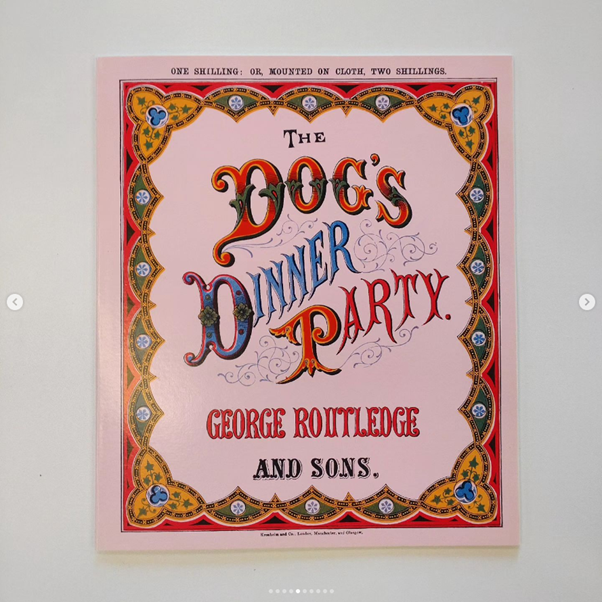

Religious texts dominate the landscape of early modern print, but our collections also reveal how these texts have been subjects for decorative book-making and manipulation well into the present day. As I mentioned in my previous post, we took Sophie Adams’ Book of common prayer (2016) with us to the Art of Books workshops in Ramsgate, into which she has folded the word ‘Prozac’. What I missed saying was that we also took two further examples of religious texts that epitomise the idea that a book is also a treasury. This edition of Wesley’s hymns still has its original early-nineteenth-century clasped binding, which (however) is so tight it’s warped the book’s covers. And this Victorian book, Parables of our Lord, is a replica of medieval manuscript with a beautiful papier-maché cover that resembles Italian church doors as if to invite the reader to open the book as a means of unlocking sacred knowledge.Other artist books we showcased deliberately conflate text and textile, notably Alison Stewart’s Fabricback novel (2010) in which each page has been uniquely crafted out of textiles to both reveal and remove the communication barrier text presents to the dyslexic individual. And if textiles can be read as texts, so too can texts feature textiles in their composition. The earliest paper in books was made of linen rag. And consider this example from our Osborne facsimiles collection: The dog’s dinner party, the cover of which truthfully announces how versions ‘mounted on cloth’ were available at a steeper price so as to resist tearing in the uncoordinated clumsy hands of small children. Such untearable editions were widely available from the 1850s, and stemmed from a growing market for picture and toy books at the time.

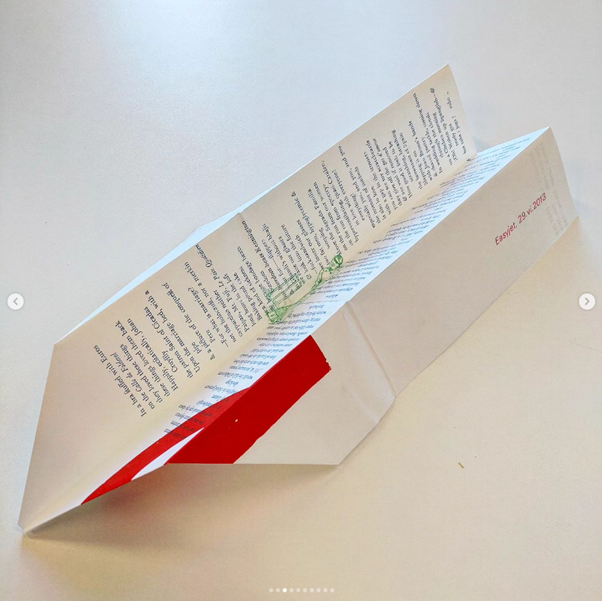

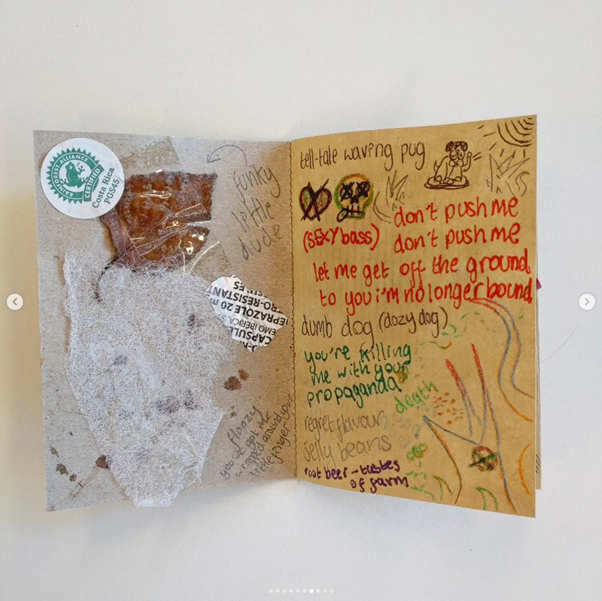

Since the objective of our workshop was to encourage children (and adults) to have a go at making books for themselves, we also showcased a variety of Special Collections items featuring multi-media or otherwise diverting forms. Ryanairpithiplanium, for instance, is a small press poem that has been deliberately, subversively, produced in the form of a paper aeroplane. And Welcome to heck is an anonymously, multi-authored scrapbook diarising events on Remembrance Day, 2018, to celebrate the Armistice Centenary. Both examples, one professional and the other amateur, play with notions of what a book is and – I hope – encourage you to play at making books too! Check out these ideas by artist Tina Lyon for some simple instructions on paper-folding and book-binding and show us what you create!