I didn’t grow up wanting to be an archivist. My one clear ambition, around the age of eight, was to be a baker in the morning and an author in the afternoon. When it came to choosing a degree I was fairly lost, after all who really knows what they want to do when they’re seventeen. I decided to do Classical and Archaeological studies, like most people simply because I liked the subject at school, and chose the University of Kent as I knew Canterbury well and found the course contained many uniquely interesting modules.

The idea of becoming an archivist came to me about halfway through my second year at Kent. I have always been fascinated by history, even as a young child, but struggled working out how to use it in my career. I couldn’t be a history teacher, neither could I see myself as a lecturer in history – I was terrified of speaking to groups of people. I couldn’t picture myself as a career historian. Despite archaeology being part of my degree title, I followed more of an Ancient History pathway, deciding archaeology was not the right fit for me.

Bizarrely I think a large influence was the BBC’s ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ I have always primarily been more interested in social and religious history than any other sphere, and I think the initial idea I had was to become a genealogist, but WDYTYA showed me archives could hold a wealth of hugely interesting and varied material, and to be working with that material, and maybe even be in charge of what happens to it, is what pulled me towards the career. I also hold a firm belief that anything of historical value should be preserved and made available for anyone who wants to see it.

So, after a couple of years of job hunting, and a year stint as a casual and Saturday girl at my local council libraries, I managed to get a job as a Metadata Assistant at my old university. I hadn’t expected to return to Kent, but I was exceedingly happy to do so. I viewed this job as more or less perfect in terms of transitioning between libraries and archives, the wealth of experience I would gain, and the direction I wanted to be going in. Needless to say I could hardly believe my luck.

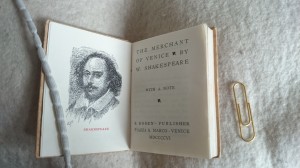

My first task was to conquer cataloguing. I had no previous experience and so have learnt everything from scratch. Initially I was focussed on regular academic books, and then I was introduced to Special Collections book cataloguing. Initially the experience was incredibly confusing. The empty catalogue record looked to me a little like a small Excel spreadsheet with a list of, (then meaningless), numbers at the side. Now it makes perfect sense to me, but at the time I found it challenging.

Later I was moved on to cataloguing for the British Cartoon Archive (BCA), which doesn’t just involve books. My principle duty is cataloguing modern political cartoons from the daily newspapers. This uses a different program to book cataloguing, so, just as I was adjusting to the first program, I was given another, totally different, one to master. Cartoon cataloguing is definitely a skill that improves with practice. The point is to enter search terms in the record that describe the cartoon, but working out what is going on in any given cartoon isn’t always straightforward. What I struggled with most was approaching this with little diverse political knowledge. I had no idea who most of the people in the cartoons even were. Now I can recognise caricatures of people, despite not knowing what they look like in reality.

A hugely important collection within the BCA is that of Carl Giles, and as part of this we have stacks of blank Christmas cards, designed by him. My first non-cataloguing job was to count these, and put them in boxes. The novelty soon wore off. Unsurprising when you consider I counted over thirteen thousand of these. However I did eventually get through them, and the sense of triumph when they were done was palpable. My work at the BCA has become more diverse, although boxes continue to play a remarkably large part in my life.

A few months into my work at Kent the BCA received a new and highly significant collection of the political cartoonist Leon Kuhn. He was an anti-war cartoonist, who campaigned alongside George Galloway’s party Respect in the 2005 general election. His work, I have learned, is unique, hard hitting, and often fairly disturbing. It is also large. I was given the task of unrolling and relocating his political posters, many of which were taller than my five feet two inches. I appreciate that for a human five foot two is not especially tall, but for rolls of paper it is pretty big, not to mention unwieldy. I also had to relocate the rest of the collection, including boxes of campaign leaflets, photos and books. I did enjoy this work, especially as it was my first real opportunity to see some of the collections, but I felt a little like a removals lady.

The work that I am proudest of taking on is of a more social nature. I have always struggled to talk to people, be they in groups, or just one person I don’t know particularly well. I often find my nerves get the better of me to the point of panic attacks. So when I was asked if I wanted to supervise volunteers in a rare book cleaning project and help out in seminars run for students using Special Collections and Archives material, my first response, both times, was panic and a distinct sense of ‘no way,’ after all I had only been in the job three months, surely there was no way I was prepared for this. I ignored my brain screaming wordlessly at me, and agreed to give both a go.

The volunteering was the easier of the two to deal with. Initially I only had one volunteer to supervise cleaning rare books in preparation for our move to the Templeman extension next year, and I was lucky that she was a happy, friendly and chatty sort of person. It went a lot better than I anticipated and I actually enjoyed doing it, which is what surprised me the most. This project has allowed my confidence to grow substantially.

The seminars were harder. There would be a group of students who would all be listening to, and for the most part looking at, me whilst I gave a run down on what Special Collections and Archives was, how to order items and how to use the material we had out in the seminar. I was shaking at the time, but I overcame my nerves, and found presenting became easier with each seminar. This came with a great sense of achievement, as I overcame my initial concerns.

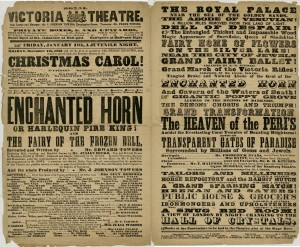

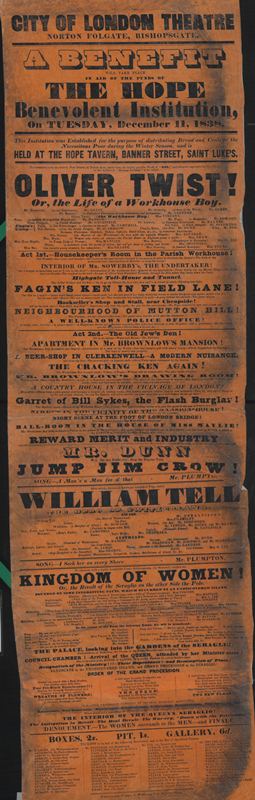

I think it’s easy to say the most interesting thing that has occurred in my brief time here was the Reading Room leak. I came in on a Monday morning to be informed it was basically raining in the reading room. Over the course of the day tiles fell off the ceiling and the carpet was soaked through, however all staff pulled together to ensure there was no major damage to any collection items. Throughout the day, and over the course of the next couple of days, I helped various other staff members remove items from the room, such as reference books, old playbills from our theatre collections, and the Indonesian shaman’s staff. (You get some weird looks when you carry that through the library and into a lift). Basically the entire of that week was a little frantic. I regularly had to leave my usual work to go and help deal with the disaster. I spent a lot of time scurrying around the building, and found I was exhausted at the end of it. But oddly I almost enjoyed the experience. Especially after we managed to save everything.

My experience has been invaluable. I have huge variety in the work I do, with ample opportunity to push myself further. I have a much clearer idea of the work archivists do, and most importantly for me I have confirmed to myself that this is the area in which I want to work. I absolutely love the work I do, although that may not always come across. Even tasks that I didn’t necessarily find easy are an important experience, and I think it’s good for archivists to be involved in their collections with work at every level. My experience of working with a variety of collections, in a variety of functions has prepared me to commit to a postgraduate course in archive management. I work in the happy knowledge that I am incredibly lucky to be working here. It took me two years following graduation to get a full time job, but now I know that it was worth the wait, and I am unbelievably happy to be back at Kent.

Rachel Dickinson