Although it’s hard to believe it, time has flown and suddenly we’re almost at the end of another term. For us in Special Collections, that means it’s exhibitions time again!

Although it’s hard to believe it, time has flown and suddenly we’re almost at the end of another term. For us in Special Collections, that means it’s exhibitions time again!

As I type, the reading room is humming in a state of barely contained excitement, and that’s just the staff. This year, we have ribbons, we have German accents, we have curtains and we have bunting; there has even been a promise of costumes for the opening on Wednesday at 4.30! Needless to say, the activity is adding excitement to a grey and rainy day.

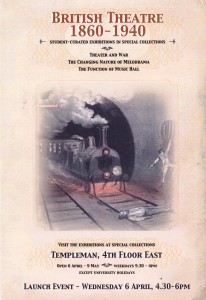

It’s hard to believe that we’re here (once again) so soon. It only seems a few weeks since all of this started back in the new year when Helen Brooks, lecturer in Drama, and I sat down with our diaries to work out the timescales for this semester’s DR575: British Theatre 1860-1940 module. The main idea of the module is to immerse students in archival material through seminars at the beginning of the term and use of sources for essays and assignments. The semester culminates in a student curated exhibition in Special Collections on a topic of the students’ choosing. In addition to this, each of the 3 groups produces a website to accompany and outlast their physical exhibition. These websites are then linked to the Special Collections website. You can have a look at last year’s exhibition pages on the website now.

We made only a few changes to last year’s module, giving each group an allotted slot in Special Collections each week (hence the Wednesday afternoon and Thursday morning closures) and bringing the deadline for the website forward to two days before the exhibition. Now we’re in April and the hard work and dedication which the 17 students of the British Theatre 1860-1940 module have shown is paying off.

As with last semester, we have 3 groups of students working on 3 very different topics:

- Theatre and war

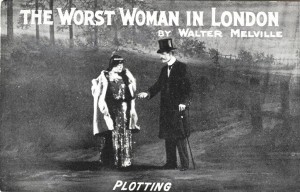

- The changing nature of melodrama

- The function of music hall

Each of the groups has carried out extensive research and is now in the process of sharing out the allotted Velcro in order to fix their materials to their exhibition boards. Today is the ‘get in’ day: all three groups have today to put up everything in order to be ready for the opening tomorrow. It’s going to be a busy day but, I’m pretty sure, it will all be very rewarding.

The exhibition opens tomorrow; there is a special launch event between 4.30-6. After that, the exhibition will be open until 9th May during normal reading room opening times (Monday-Friday, 9.30-1 and 2-4.30) excluding public holidays. I intend to have the web pages live as soon as possible, so that even those of you who can’t journey all the way to Canterbury for the exhibition can still enjoy the event.

Once again, my thanks go out to all of the students for working incredibly hard and listening attentively to me endlessly repeating our rules about the handling and use of archival materials. Huge thanks are also due to Helen Brooks, who came up with the idea of student curated exhibitions using Special Collections materials and who has been innovative and enthusiastic in her use of archival material, as well as inspiring her students and others to use the collections.

Sadly, this module won’t be running next academic year, but we hope that it will be back in the autumn of 2012, better than ever! In the meantime, please do come along to have a look at the exhibition and let us know what you think.