Karen Brayshaw, Special Collections and Archives Manager

Welcome to the Special Collections and Archives annual highlights 2025. It’s always a pleasure to look back at what has taken place in the University’s Special Collections and Archives, and I’m always amazed at how much the team achieve – well done Team! This year some changes have taken place at the University and as a result Library Services (of which we are part) has now joined the Student Life Directorate. Don’t worry though – you can still find us in the same place. As a Team we said goodbye to Beth, our University Archivist. Beth joined us as Project Archivist for the UK Philanthropy Archive, before taking over the post of University Archivist. We wish Beth well in her new post. In September we also said goodbye to Sam Datlen, Project Digital Administrator. Sam has worked with us on a part-time basis since 2023, digitising the original artworks of Lawrie Siggs, Geoff Laws, Ron McTrusty and some of the Donald McGill collection. Although we said goodbye to Sam as a colleague we are delighted he has agreed to continue to come on to work on some of our volunteer projects.

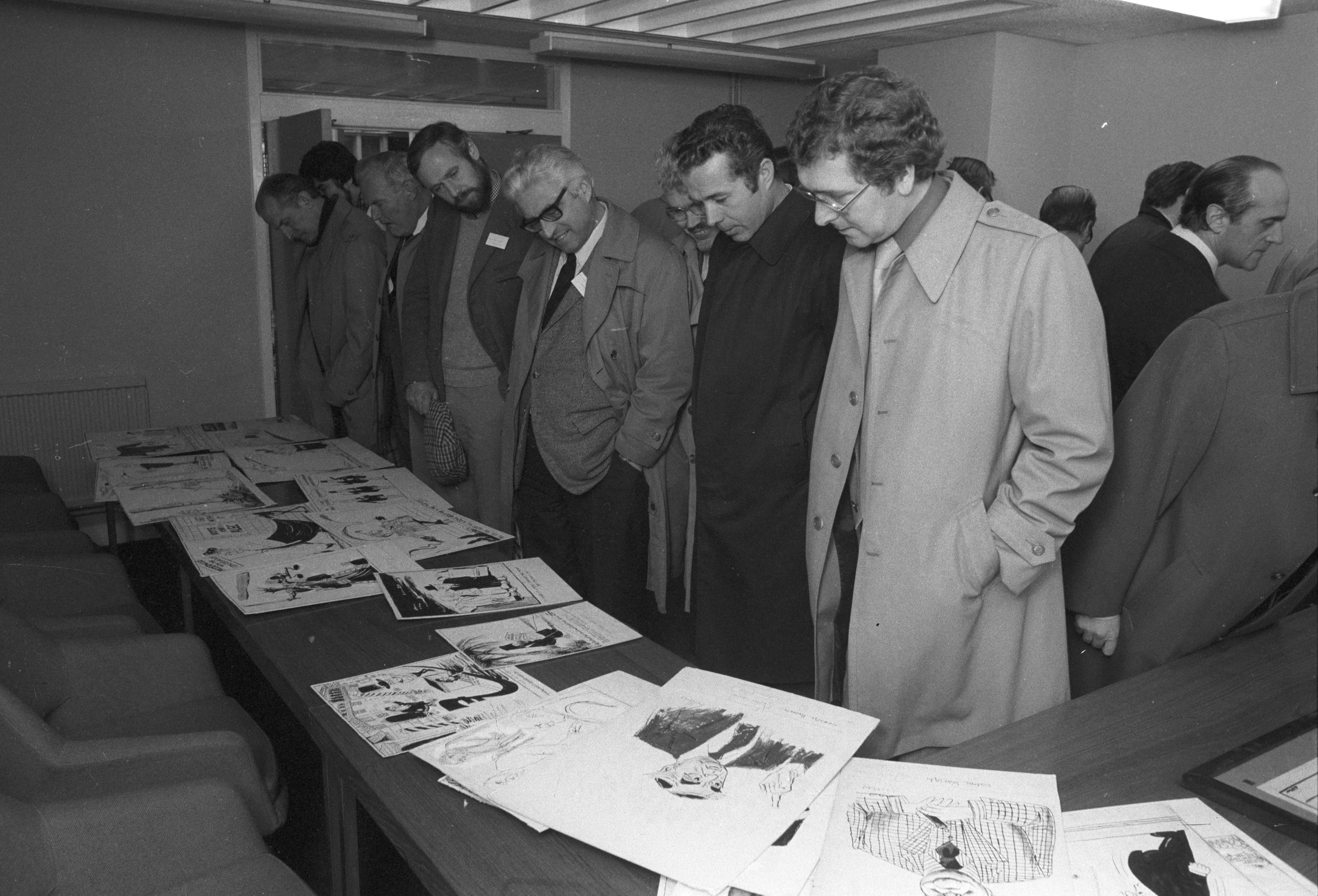

Photograph from c. 1978 – Early days of the Centre for Cartoons and Caricature, now the British Cartoon Archive (University Archive UKA/PHO/1/1039)

This year it was 50 years since the inaugural lecture took place to launch the Centre for the Study of Cartoons and Caricature. The collections have grown enormously since then and to celebrate we hosted an exhibition. It was amazing to work with Clair on this. The activity was funded by the Beaverbrook Foundation, which covered the cost of two scholars and three interns and they were a delight to work with. The exhibition has been a huge success and there is still time to see it if you missed it, as it will remain on view during the first two weeks of January.

I don’t know about you, but I enjoy a good podcast and what better time of year is there to do just that. Clair and Christine feature in two separate podcasts, you can read all about it below and do treat yourself and have a listen.

Clair and Jacqueline have been working on Dr. R.E.W. Maddison’s collection, which arrived at the University in 1985. The collection is fascinating and they’ve both discovered some treasures – more of which you can read below. The printed works are available to browse via our online catalogue. The archival material is also available but more detailed work is being undertaken in the new year.

Christine continues to deliver an array of excellent and diverse sessions for our engagement and education activities, using her best Miss Marple skills to uncover treasures for our participants – eat your heart out Poirot. Although she doesn’t mention it here Christine is also doing some brilliant work with volunteers to sort out and make available our extensive theatre programme collections and many more have been added to our catalogue for your perusal.

This year we welcomed Emily to our team. Emily is Project Archivist, working on the UK Philanthropy archives, which continues to grow. As I type this, we await the latest addition to the archives… watch this space for more news next year!

We’re very lucky that we have managed to secure funding to retain the services of Jacqueline, our Project cataloguer. Although Jacqueline is with us part-time, she has managed to catalogue at least six collections over the last few years, which equates to several thousand books! Her latest target is the Ronald Balwin collection, which is turning up some real treasures. I know I’m looking forward to seeing what she unearths in the new year.

Soon we will have all the John Jensen original artworks available online as Alex has almost completed digitising them. At the same time he is exploring the audio material in the Max Tyler collection – we hope to have more to share with you about that next year.

Mandy also continues to digitise our cartoon cuttings as well as supplying the images for the Giles Annual every December and January. Mandy also supports us with requests for digitised material from staff and readers – including interesting scripts (of one of my all-time favourite programmes!)

Stuart and Matthias, our Curation and Discovery colleagues have been working their way through a variety of material, including books about cartoons, literature and sheet music, as well as our digital cartoons. This means there is now more than ever available online for everyone to access through our online catalogues.

And finally we have the contribution made by our volunteer community – our volunteers bring so much to our team. By giving us their time we are able to progress the processing of our collections and ultimately, we can make them accessible to everyone. So it’s a HUGE thanks from me to them.

Clair Waller, Digital Archivist

British Cartoon Archive – 50 years

2025 marks 50 years since the formal opening of the Centre for the Study of Cartoons and Caricature (now known as the British Cartoon Archive) and it’s been a bumper year of activity.

Beaverbrook exhibition

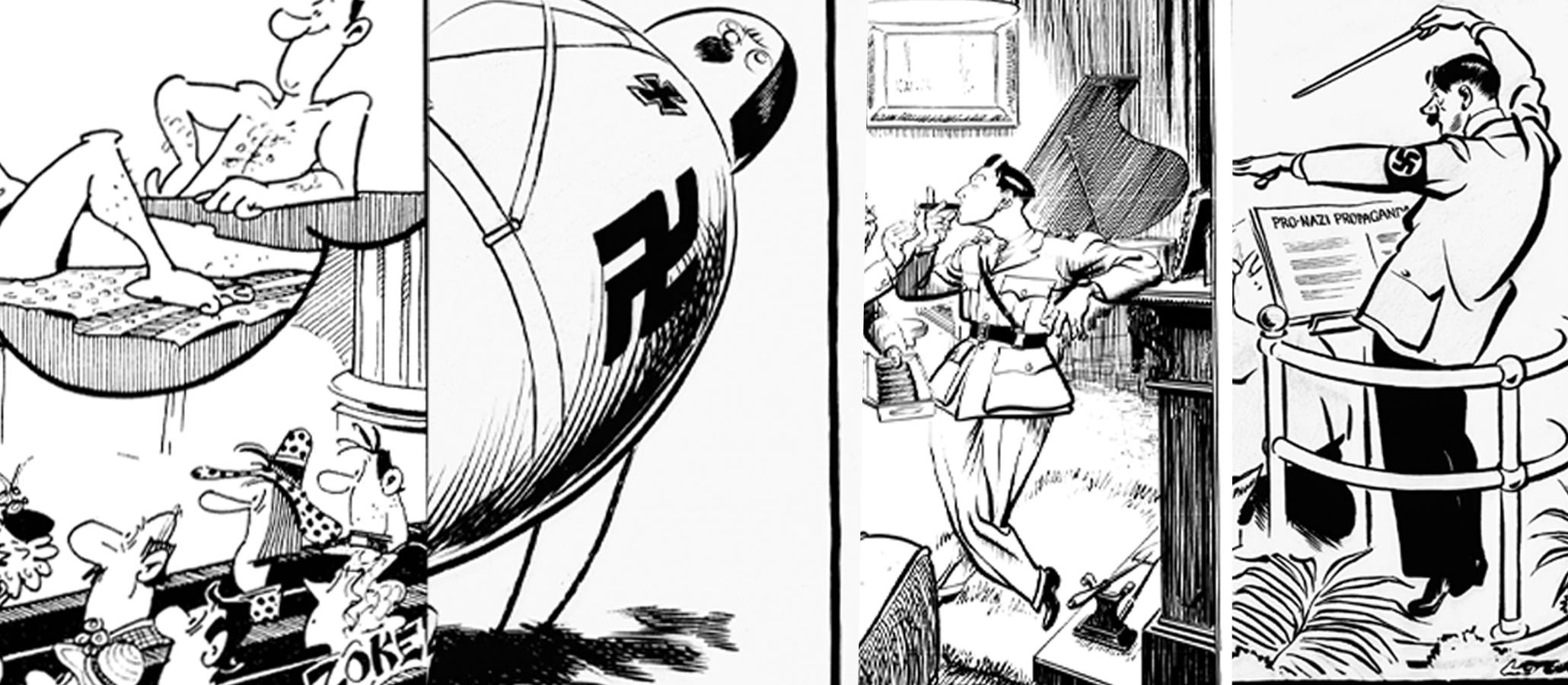

Images from the British Cartoon Archive left to right: Zoke [Michael Attwell], ‘Ah-men!’ [46886] ; David Low, ‘All blown up and nowere [sic] to go’ [DL0741a] ; Joseph Lee, ‘Smiling through: queer new world’ [JL 2539] ; David Low, [no caption] [DL1613].

[Update – see Amy’s article at https://doi.org/10.1080/14714787.2025.2576832]

new additions

The British Cartoon Archive has seen a number of additions to the collection this year. This included a collection of almost 100 originals of the cult satirical cartoon strip ‘Biff’, created by Mick Kidd and Chris Garratt, and a selection of original cartoons by Jeremy ‘Banx’ Banks. We were also very lucky to acquire a large collection of underground comics from Tony Bennet of long-standing alternative UK publisher, Knockabout. The collection not only spans over 50 years of underground and alternative comics from the UK and beyond, but also includes documentation and papers related to several legal cases brought against the company for breaches of the Obscene Publications Act.

cartoon county, brighton

In August 2025 the British Cartoon Archive was invited to talk at a meeting in Brighton run by Cartoon County, a community group of local artists and storytellers. These events are held on the last Monday of every month, with host Alex Fitch inviting different speakers to come along and share their current work, after which Alex broadcasts the talks on Resonance FM’s Panel Borders. I was delighted to attend and had a great time speaking to the group about the work we do at the BCA. I can highly recommend attending if you find yourself in Brighton on a Monday evening!

The R.E.W. Maddison Archive

Dr. R.E.W. Maddison’s library has been a fixture of Special Collections and Archives, and the Templeman Library, since our university’s early days. Maddison was a personal friend of a fellow bibliophile, John Crow, whose own library constituted one of the University’s founding collections and who encouraged Maddison to deposit his with us too. Maddison’s library was built up over a period of 40 years and was considered one of the finest private collections on the history of chemistry. Alongside his large collection of books (read more in Jacqueline’s entry below), we were also gifted a substantial archive of material from his career, which I have had the pleasure of cataloguing this year.

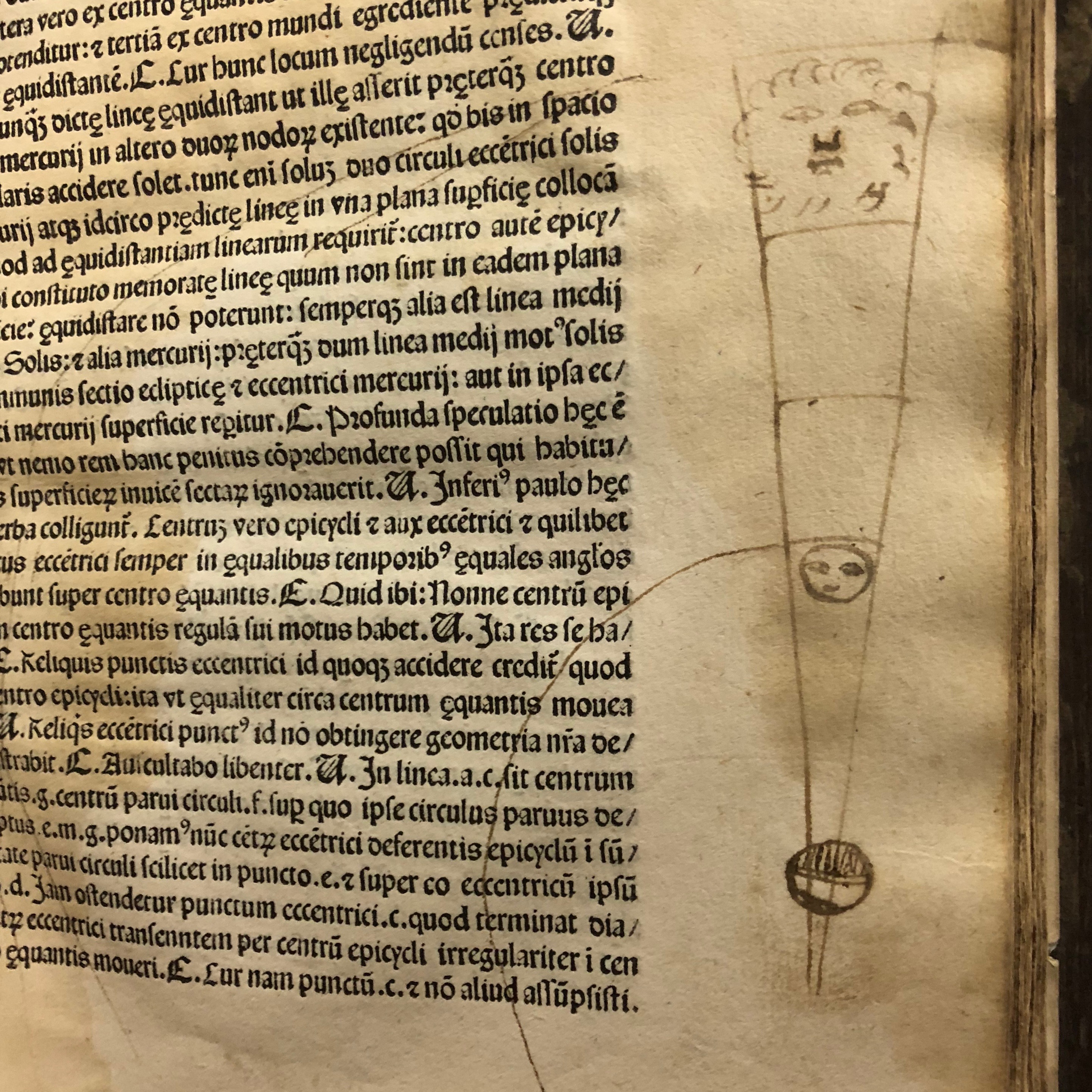

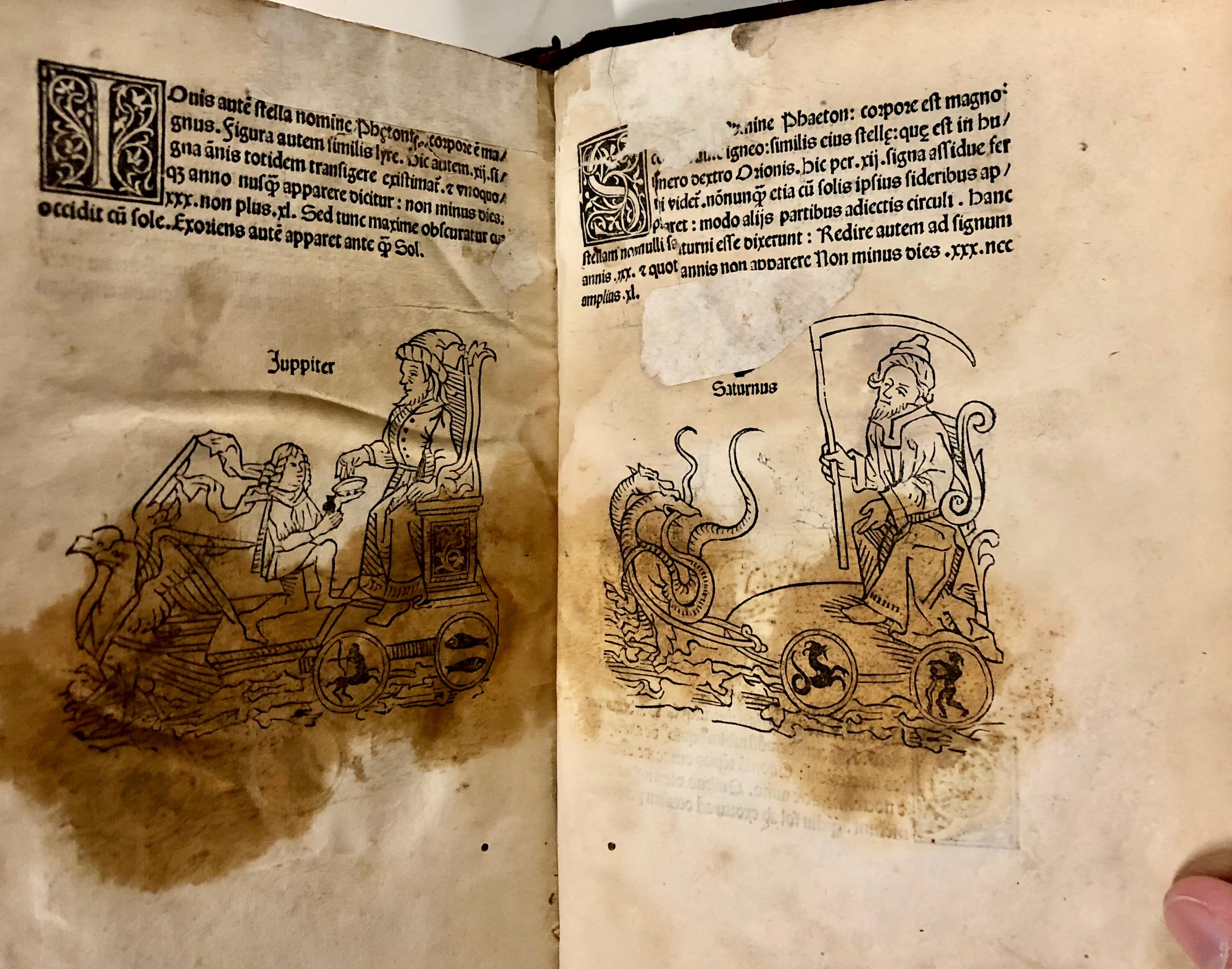

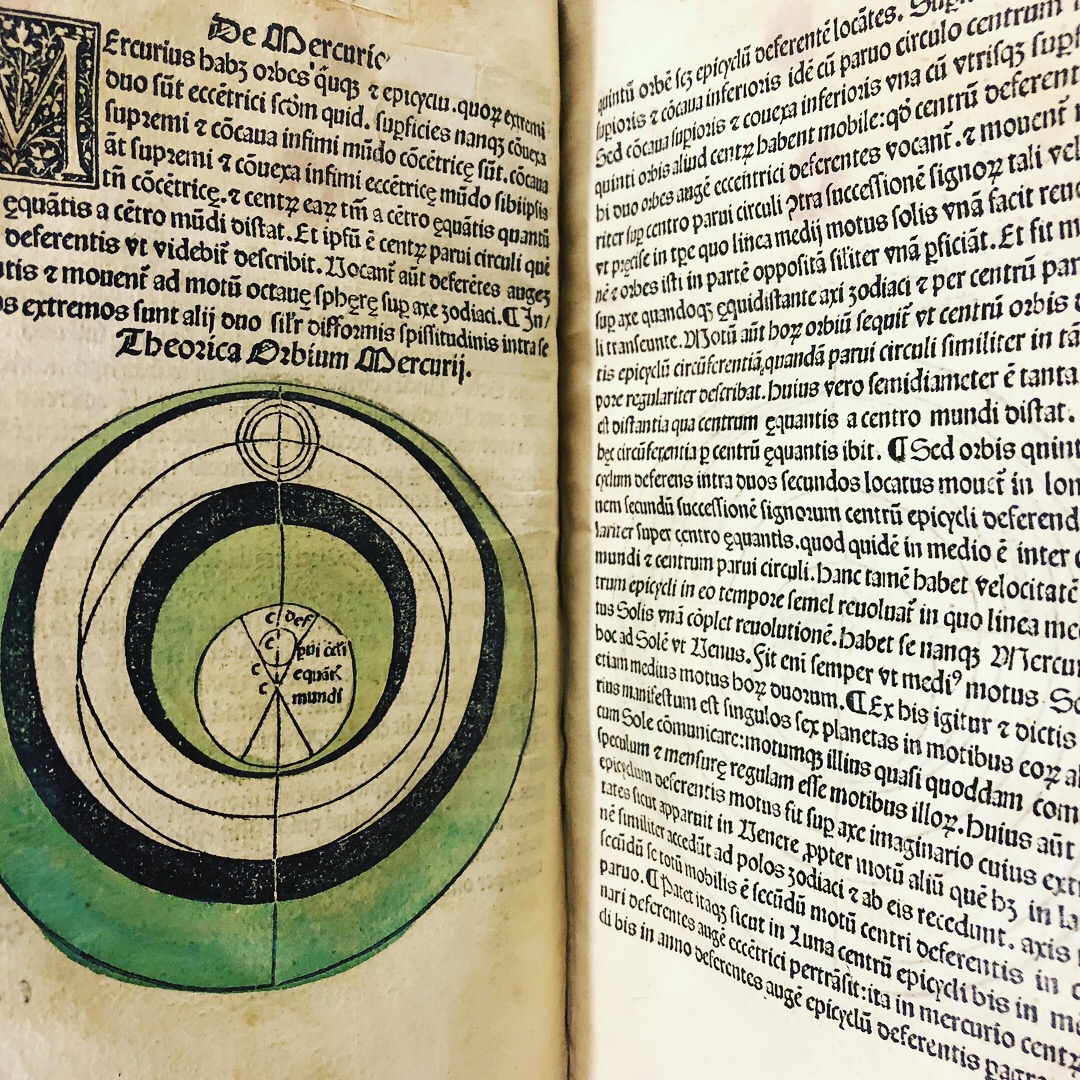

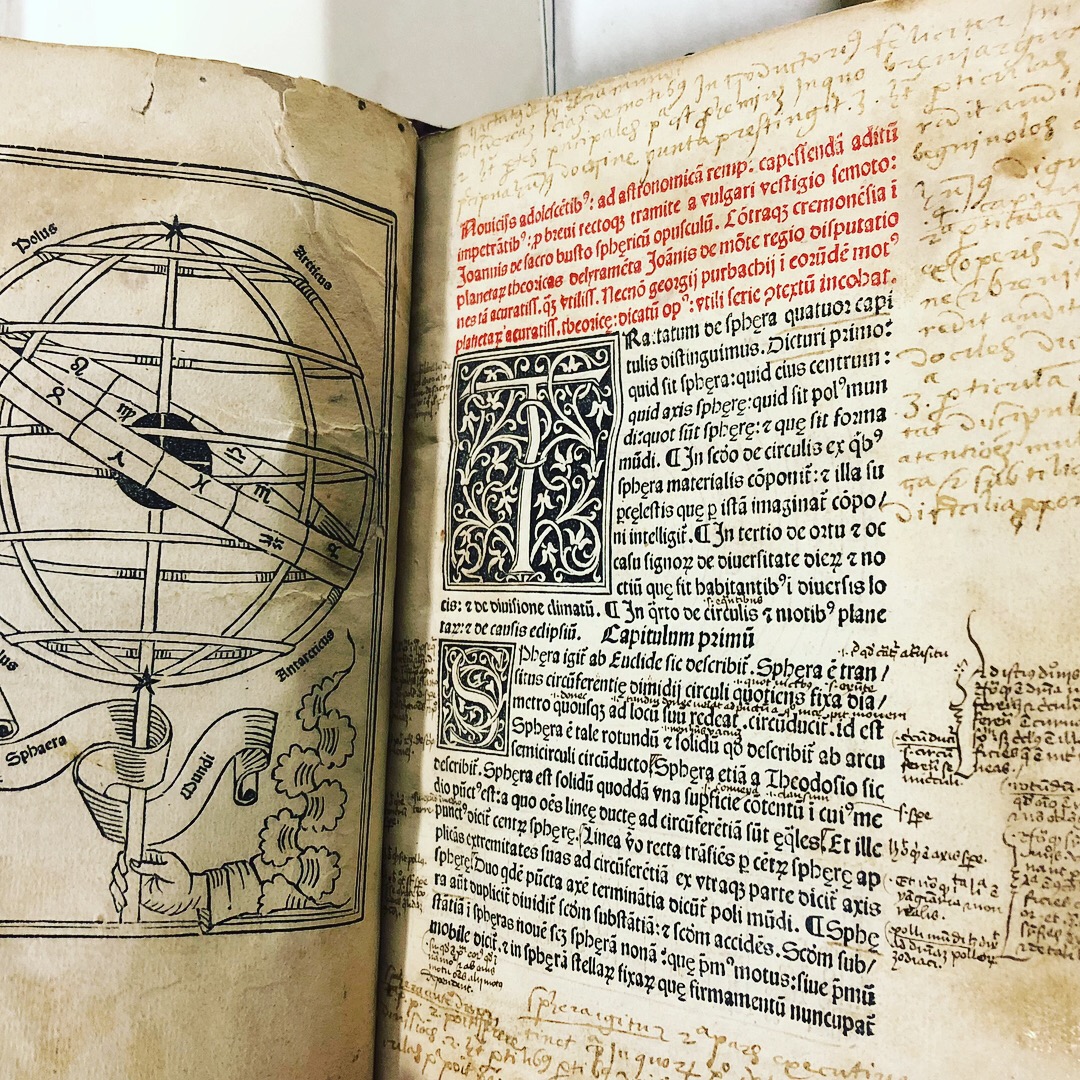

The archive contains many different aspects, including correspondence, research papers, scrapbooks, published pamphlets, prints, and Maddison’s own notebooks. Particularly exciting items I identified whilst working on the collection include some 18th century Gillray cartoon prints and many beautiful early-printed engravings depicting scientific instruments and diagrams. It’s been very satisfying to bring the collection to order and to make it accessible, so have a browse on our online catalogue.

Christine Davies, Special Collections and Archives Coordinator

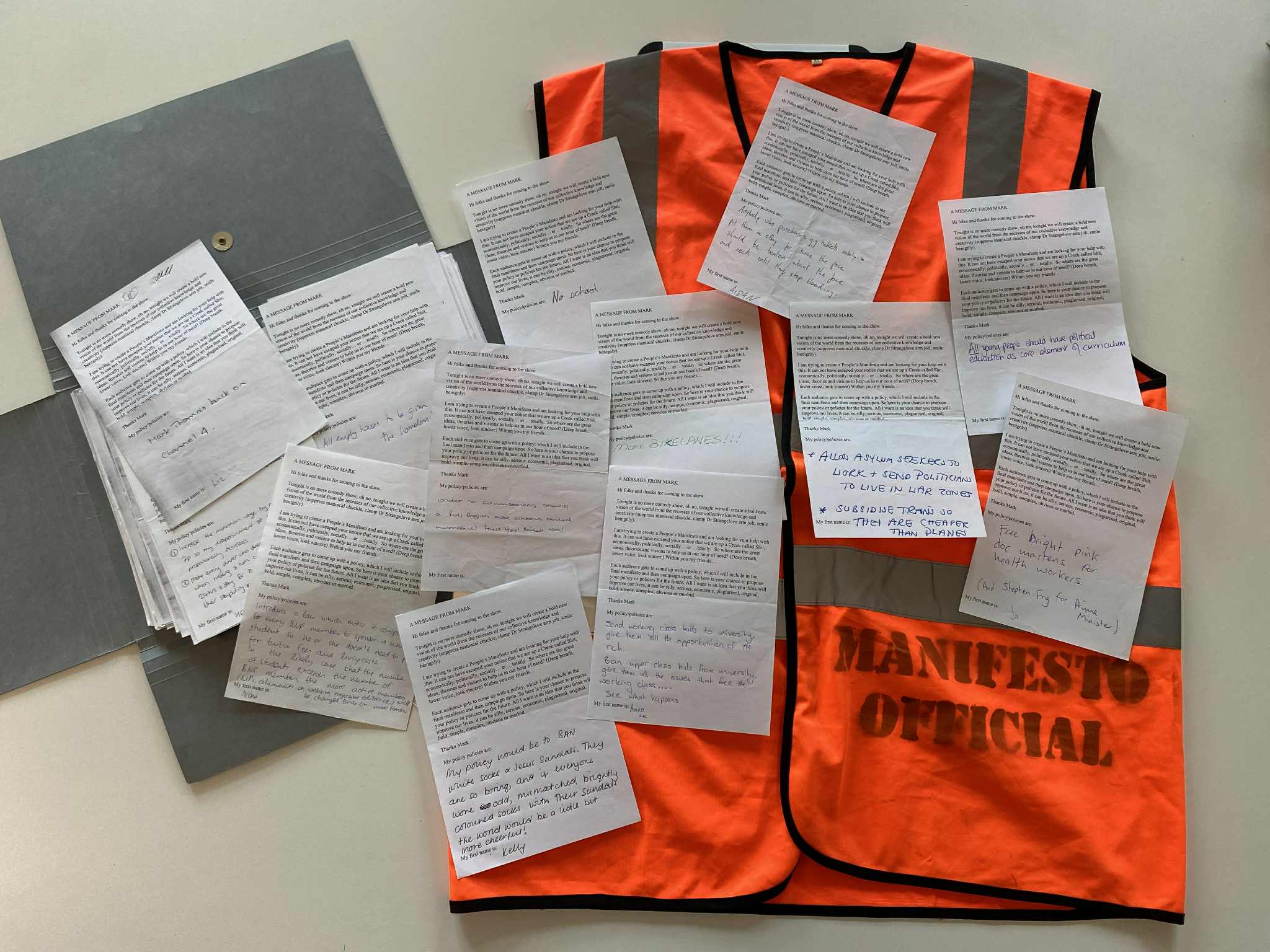

One of the privileges of my role lies in the diversity of projects and groups of people I get to support with engagement and education activities. This year, one of the highlights was working with David Smith (Outreach & Widening Participation, University of Kent) in delivering two bespoke sessions for secondary school students about protest and activism, showcasing some of the wacky materials from the Mark Thomas Collection (including a toy Barbie car and hi-vis demonstration jackets) and crafting zines with which to empower their own civic voice.

Audience contribution slips and hi-vis jacket from Mark Thomas’ It’s the stupid economy tour, 2009 (Mark Thomas Collection, BSUCA/MT/2/12/1 and BSUCA/MT/12)

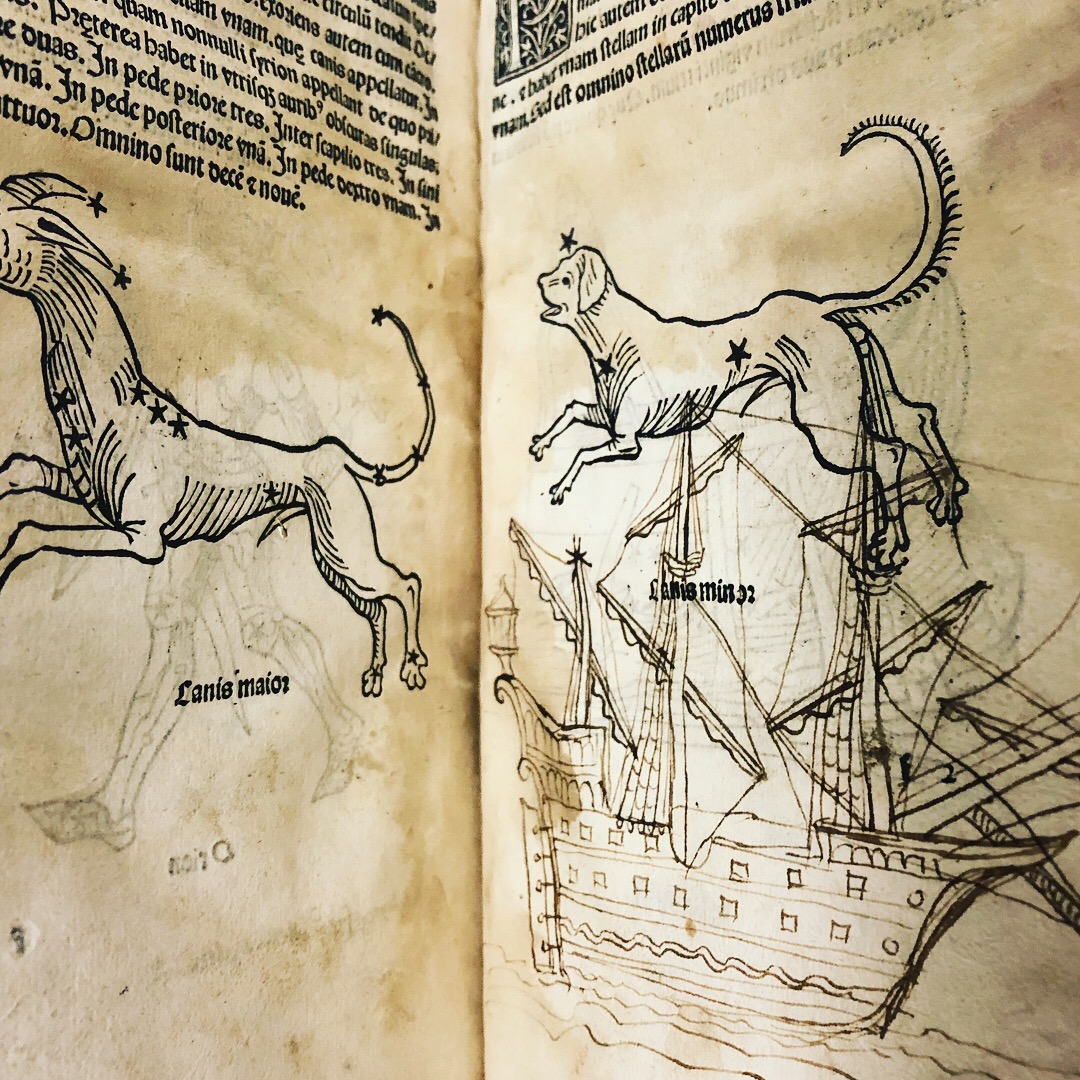

Another highlight was in supporting the wider Library Events Group with a social media campaign to celebrate Shakespeare’s Birth Year; it was thrilling to uncover so much unique material in our collections testifying to both the literary and social contexts of Shakespeare’s lifetime and the enduring performance legacy of his plays. We also created a pop-up display of these materials to complement a talk given by Dr Rory Loughnane (School of English, University of Kent) in which he shared research for his upcoming book – favourites included a 1502 copy of Cicero’s Tullius de officiis, a text Shakespeare would have recognised from the school he attended, a copy having been bequeathed by local vicar John Bretchgirdle in 1564, and several 19th-century libretti that were used by Arthur Williams as prompt-copies in Victorian productions of Othello featuring his annotations and paste-ins as well as intriguing printed front-matter about contemporary casts and costume recommendations.

Lasty, and most recently, I collaborated with Dr Bala Chandra (School of Advanced Study, University of London) in a series of activities to coincide with the Being Human Festival, engaging the wider public with prominent literary and cultural figures associated with Canterbury through a curated display of our materials and a radio podcast now on Spotify.

Emily Royston, Project Archivist

This year brought about an exciting change for me as I joined the team in April as Project Archivist! Since stepping into the role, I’ve been working closely with the UK Philanthropy Archive (UKPA), appraising, cataloguing, and rehousing our newest collections. These include major acquisitions such as the Craigmyle Fundraising Consultants Archive, the Wates Foundation Collection, the John Ellerman Foundation Collection, and the Hilden Charitable Fund Archive. Recently established in 2019 with the late Dame Stephanie Shirley’s founding collection, the UKPA will benefit enormously from these additions, opening up fresh avenues for research into UK philanthropy and fundraising.

I’ve really enjoyed diving into our newest collections from the Wates Foundation and the John Ellerman Foundation, which has revealed the distinct yet complementary stories of two family-endowed trusts. The Wates Foundation Collection traces the work of a trust set up in 1966 by brothers Allan, Norman, and Ronald Wates, who earned their wealth in the building industry. As generalist grant-makers, the Foundation has supported a wide range of causes from housing and homelessness to young people and education, women’s health and wellbeing, and criminal justice and prison reform. Its records, including grant files, correspondence, publications, photographs, and audiovisual materials, offer a vivid picture of family-driven, community-focused philanthropy.

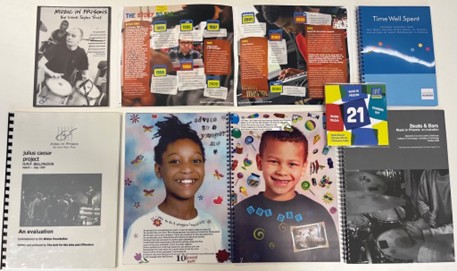

Arts and music projects supported by Wates Foundation and The Irene Taylor Trust, part of their work in prison reform and rehabilitation (UKPA/WATE/3/144)

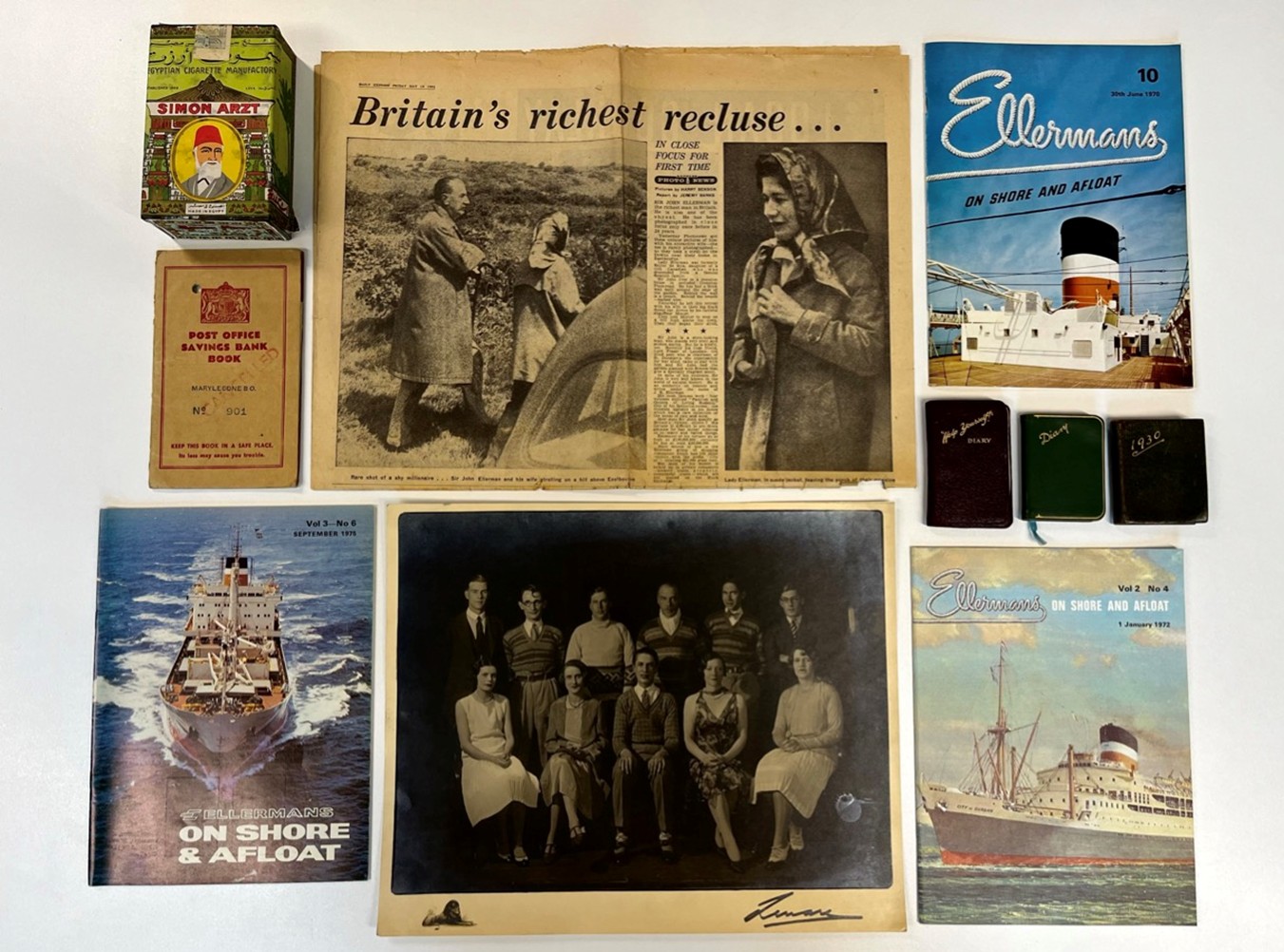

The John Ellerman Foundation Collection, meanwhile, captures the legacy of a trust established in 1971 by John Ellerman II who inherited the fortune of his father, shipowner and investor Sir John Ellerman I. Its grant-making spans both UK-based charities and international projects, including support for disability organisations in South Africa. Also present in the collection are the Ellerman family’s personal photographs, records, and belongings, providing a rare insight into a family often described in the press as reserved and elusive. Together, these collections provide a rich and exciting resource for researchers, offering insight into how philanthropy and grant-making have shaped communities in the UK and beyond.

Newspaper clippings, publications, and personal belongings from the John Ellerman Foundation Collection (UKPA/JEF/1—4)

Making these collections accessible to researchers this year has been incredibly rewarding, with scholars traveling from as far afield as Japan and the United States to consult our UKPA materials. As our UKPA collections continue to grow, I’m excited to see the new research they inspire in 2026!

Jacqueline Spencer, Project Curation and Discovery Administrator

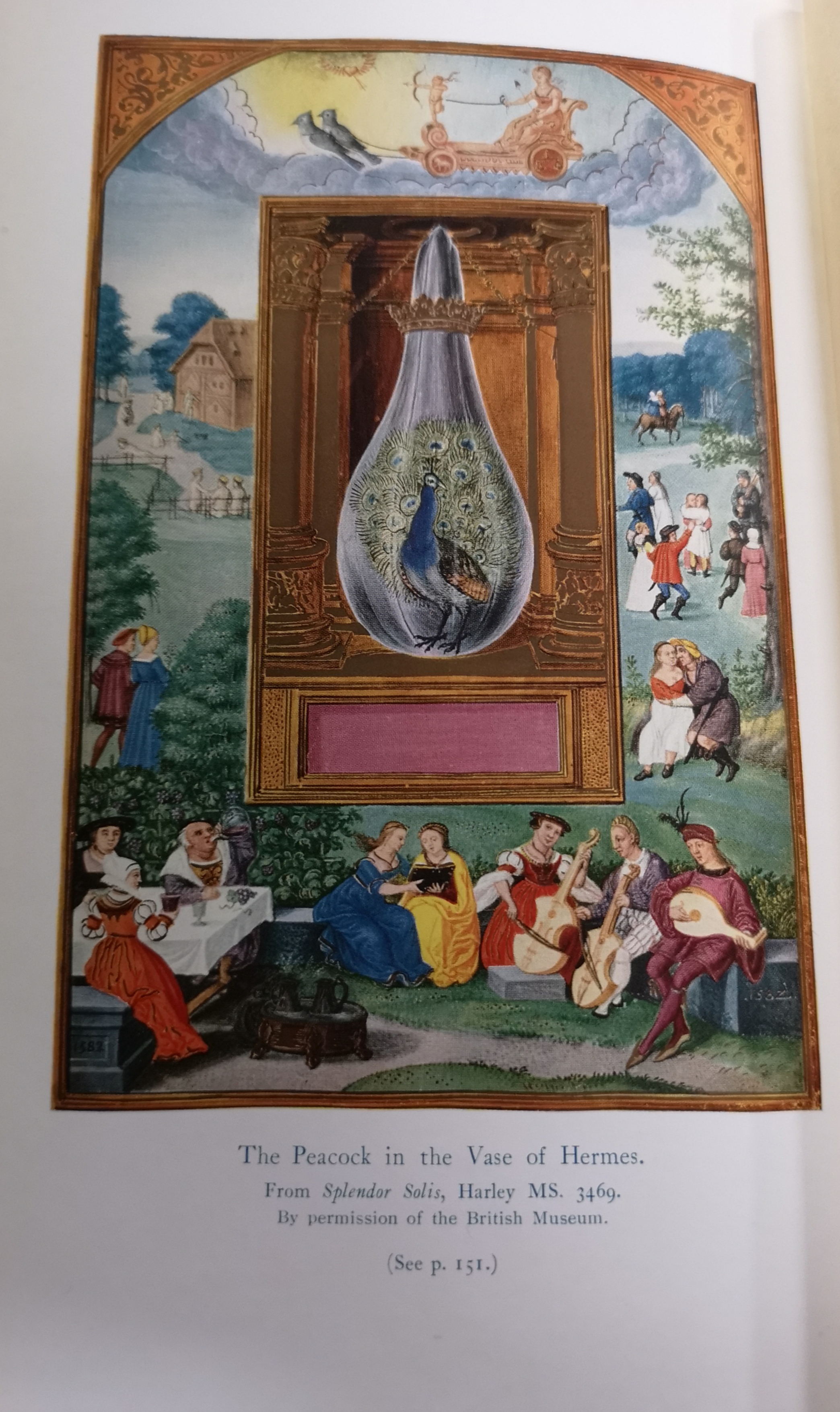

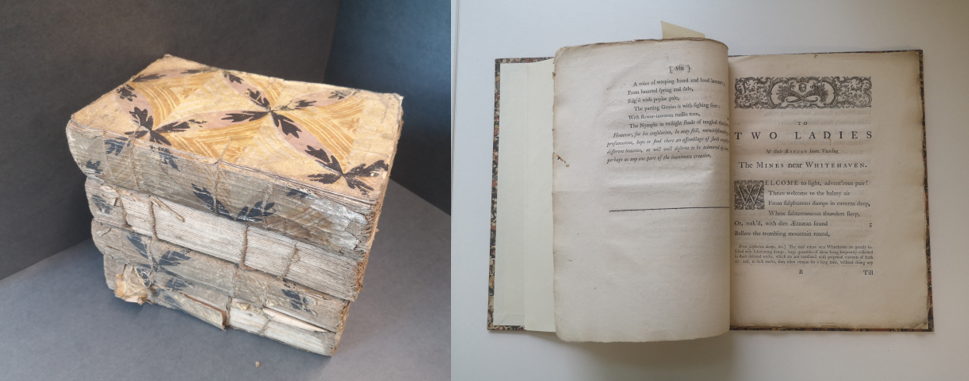

This year I have enjoyed working with the collections of two extraordinary book collectors, Dr. R.E.W. Maddison and Ronald A. Baldwin, Kent historian. Dr. R.E.W. Maddison was an academic and librarian of the Royal Astronomical Society who wrote the major work on Robert Boyle (1627-1691). His collection spans the history of sciences, particularly physics. In 2025 I completed the cataloguing of his later deposit of about 800 books including works on alchemy, astronomy and applied science. Dedications and notes in some of the books indicate Maddison’s personal connections with scholars across Europe. The older books include a four-volume set of the 1787 Paris edition of M. Sigaud de la Fond’s Eléméns de physique bound in block-printed pastepaper and John Dalton’s A descriptive poem addressed to two ladies at their return from viewing the mines near Whitehaven (1755) which indicate the range of his interests.

Élémens de Physique (Maddison Collection, QC 19 FON)

A descriptive poem [of…] the mines near Whitehaven (Maddison Collection, LRG PR 3395 DAL)

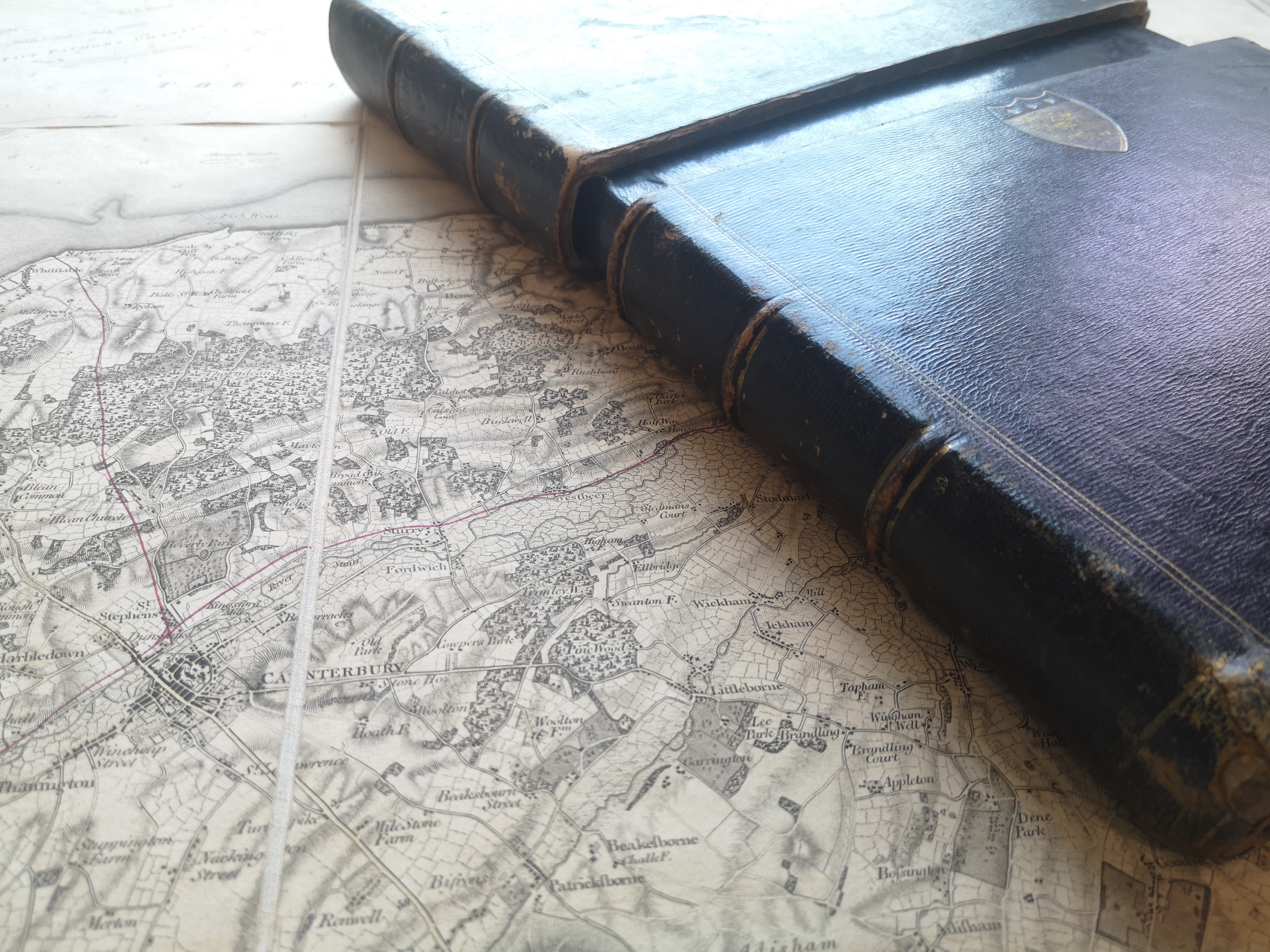

An entirely new & accurate survey of the County of Kent (Ronald A. Baldwin Collection, G 5753.K4 1801)

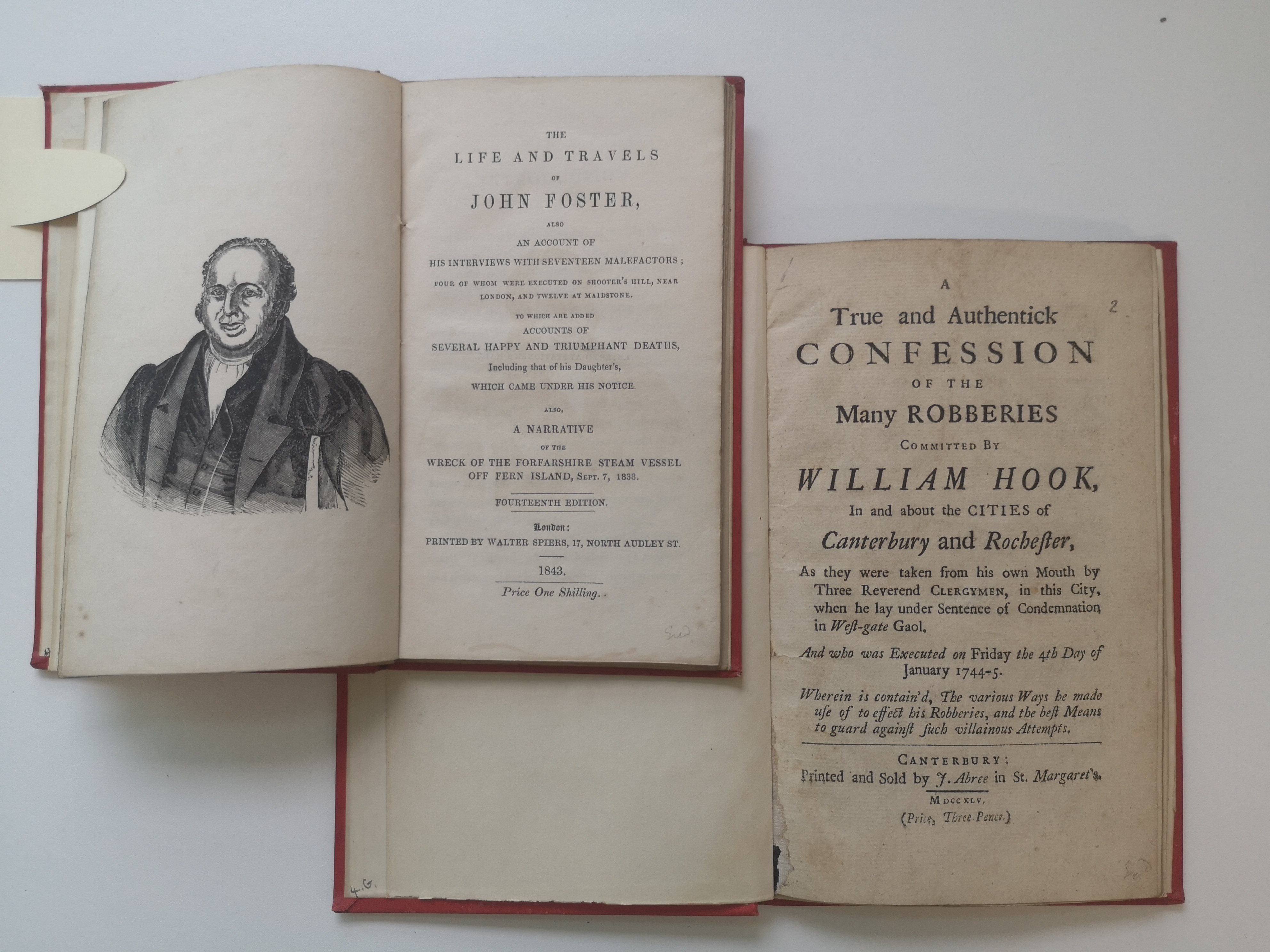

Railway lines have been drawn on in red pen which, Baldwin notes, must have been before 1860 as the Crab and Winkle line is shown but not the line from Canterbury to Faversham. Baldwin assembled Acts of Parliament relating to the use of land and rivers in Kent and he sought out sources on local government and on crime. He was a Methodist and his interest in religious biographies may have helped him to acquire scarce pamphlets, amongst which is the rarest book I have ever catalogued, his pamphlet printed by James Abree in St. Margaret’s, Canterbury in 1745, A true and authentick confession of the many robberies committed by William Hook …the notorious house-breaker; our copy has now been added to the ESTC (English Short Title Catalogue) by Dr. David Shaw. I have been able to catalogue part of his collection this year; the biographies of people of Kent, of Kent authors and religious nonconformist groups are yet to be explored.

The life and travels of John Foster (Ronald A. Baldwin Collection, HV 28 FOS)

A true and authentick confession of the many robberies committed by William Hook (Ronald A. Baldwin Collection, HV 6653 HOO)

Alex Triggs, Digitisation Administrator

During 2025 I continued with the high resolution digitisation of the British Cartoon Archive collections. This year has been dominated by the original artworks of Jensen (John Jensen, 1930-2018), who drew for a wide range of publications; newspapers, books and magazines, but is perhaps most widely known for his work for Punch magazine and the Telegraph newspapers. Born in Australia Jensen came to Britain as a young man and began his career as a cartoonist and illustrator which went on to span six decades. He was a skilled artist who could draw with either hand and in a wide variety of styles. The Jensen collection contains circa 3000 artworks and is now almost entirely digitised. Personally it has been one of the most interesting collections I have worked on, largely due to Jensen’s artistic ability and stylistic diversity.

The focus of my digitisation work on the audio visual collections has now moved on to the vast Max Tyler collection of Music Hall analogue magnetic audio cassette tape recordings. Max Tyler was the archivist and historian for the British Music Hall Society, and this substantial collection includes a wide variety of Music Hall memorabilia including sheet music, playbills, books and recordings. We are currently running an initial test digitisation of this eclectic collection of audio recordings to evaluate how we will approach the process as we move forward.

Mandy Green, Special Collections and Archives Assistant

Back in January I completed scans from the Giles annuals that we receive every year, they are always so good to scan and the comedy element always funny. I’ve also been scanning the Donald McGill postcards which are particularly colourful and detailed. Most recently, I have scanned two of the Alexei Sayle scripts for the Young Ones, it was so interesting to see how the scripts are written.

Stuart Tombs, Curation and Discovery Administrator

This year, as well as cataloguing many more music hall song sheets from the Max Tyler collection, I have enjoyed cataloguing items for the Reading-Rayner Literature Collection. These have consisted mainly of twentieth century fiction and biographical works by authors including Charles Morgan, Evelyn Waugh, T. H. White, Jerome K. Jerome, and Gore Vidal (including a copy of his memoir, Palimpsest, signed by the author).

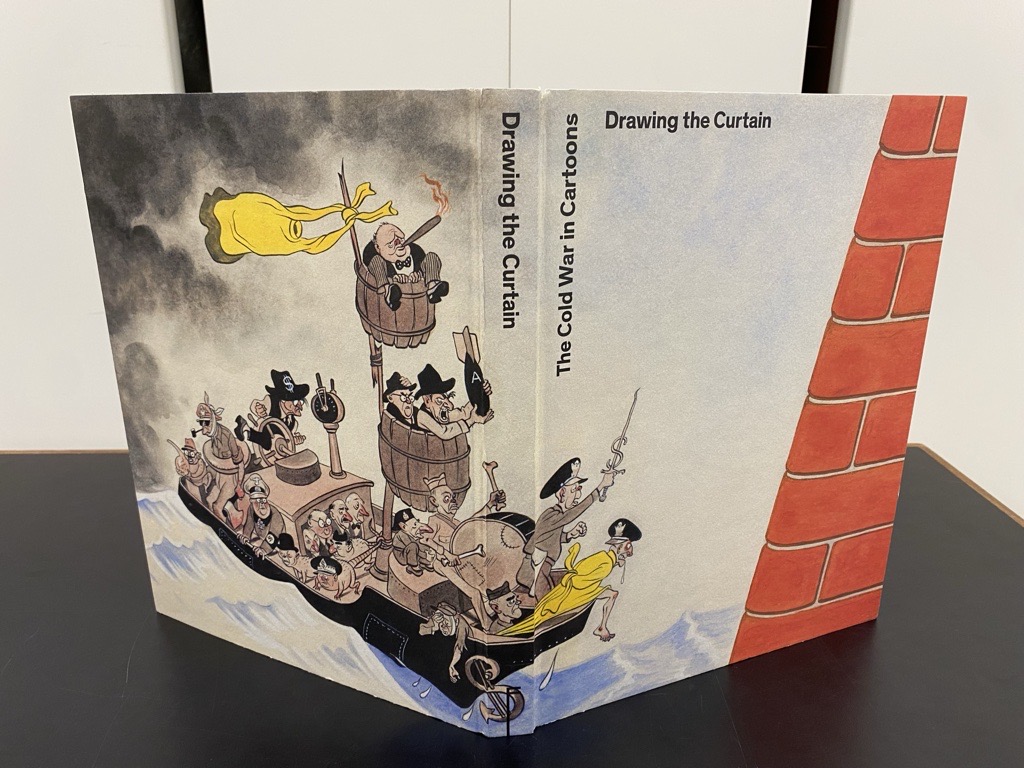

Many more interesting items have been added to the British Cartoon Archive of which the highlight for me has been “Drawing the curtain: the Cold War in cartoons”, a beautifully presented collection of Soviet cartoons from the Cold War era, published in 2012. Sergei Kruschev (Engineer, and son of Cold War Russian leader Nikita Kruschev), in his preface describes it as “a history of the second half of the twentieth century: from the gentle humour of the mid-1940s, when the world lived in a state of euphoric anticipation of peace and prosperity to come; through the mutual mistrust – not to say hatred – of the 1950s to 1970s; right up to the hopes of perestroika, and even the diplomatic ‘reboots’ of modern times.”

Drawing the curtain : the Cold War in cartoons (British Cartoon Archive Library, LRG NC 1763.W3 ALT)

Matthias Werner, Curation and Discovery Administrator

I have started to work on a collection of books and periodicals generously gifted to us by the late Graham Thomas, who sadly passed away in 2023. Dr Graham Thomas was a former Politics lecturer at the University of Kent and played an instrumental role in establishing the Centre for the Study of Cartoons and Caricature, now known as the British Cartoon Archive. He left us a substantial collection, comprising a large number of books and periodicals, an extensive postcard archive, and a significant assortment of ceramics. The Graham Thomas book and periodical collection includes works of cartoon and caricature artists, but also books on humour, drawing and design. Among the highlights are a number of first editions by Fougasse, George Molnar and Francis Carruthers Gould.

In addition, I have continued to catalogue Steve Bell’s cartoons for the British Cartoon Archive, making them available to the public. Steve has very kindly sent us his published editorial cartoons from The Guardian. It has been fascinating to revisit the political scandals of 2021, which made me realise how quickly things in politics have moved, although the broader topics have largely remained the same as we continue to battle with the fallout from Covid, Brexit, and the (first) Trump presidency.

Volunteers

We couldn’t end our annual newsletter without a massive thank you to all our volunteers, who provide indispensable support to managing our collections and making them more discoverable. Collectively, they contributed 1031 hours over the last twelve months – equivalent to 186 full work days. Read on for some of their own insights.

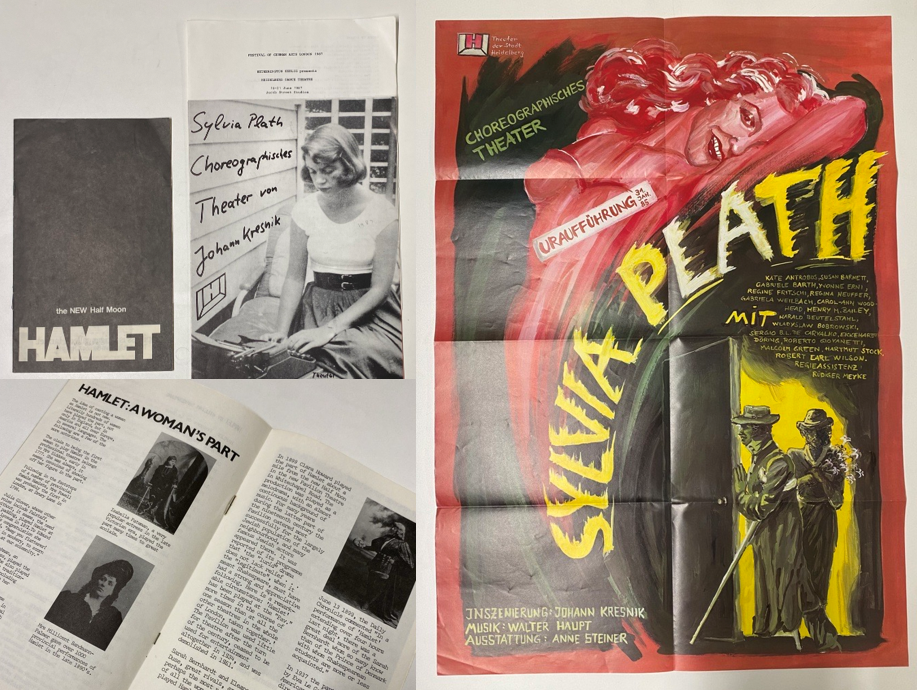

Martha Pledge

I have been volunteering in Special Collections and Archives since the spring. Most of my time has been spent archiving theatre programmes gifted to the university by Seona McKinnon and I’ve made some fascinating finds. This Sylvia Plath programme features her poems, a timeline of her life, and a scene sequence of her poetry to the dance movements performed. It even folds out to become an amazing poster, revealing a creativity of production which reflects beautifully on the legacy of Plath’s life and work. As a Shakespeare lover, I also want to highlight this 1979 adaptation of Hamlet at the Half Moon Theatre, starring Frances de la Tour in the title role. A more traditionally-structured programme, it includes an article on the lesser-known performance history of Hamlet being played by female actors. These are just two of hundreds of programmes I’ve encountered whilst volunteering, all of which has reminded me of the importance of preserving literature for future academics and students.

Programmes for productions of Hamlet (Half Moon Theatre, 1979) and Sylvia Plath (Heidelberg Dance Theatre at Jacob Street Studios, 1987). Seona McKinnon Collection

Emma Jeffree

As a Special Collections and Archives volunteer, I have been writing summaries and editing transcripts of interviews in the Winstanley Oral History Collection. These interviews were conducted by Michael Winstanley in the 1970s, looking at everyday life in Kent before 1914, and formed the basis for his book Life in Kent at the turn of the century [1978]. Listening to the original digitised recordings has given me the chance to hear the voices of people who lived at the time, and learn from them what their life was like, and how society worked 100 years before I was born. Having grown up in Kent myself, it is fascinating to hear of familiar places in very different lights. Volunteering at the archives is not only interesting and enjoyable, but it also provides me with good work experience vital for a student and the confidence and skill set necessary to embark on my future career.