In addition to keeping the Templeman Library a welcoming place for all, our Learning Environment Assistant Christine Davies spent some time job-shadowing us in SC&A last year. We hope you enjoy this second blog post by her, read part one here.

I like to think of the Templeman Library as an iceberg.

As you enter the building, you encounter an expansive main collection – books, journals, DVDs, arranged by format and subject area across four blocks and as many floors. I work in Learning Environment (LE), where we manage the physical circulation of these items.

Lockdown in March 2020 meant closing the building and adapting our services, but before too long we were able to re-open a Covid-secure library. For LE, that included re-shelving end-of-term returns, numbering no fewer than 20,000 books! Fortunately, I have superb colleagues whose many hands make light work. And, to be honest, it was a welcome work-out after months of desk-based operations.

As we manoeuvre our book trolleys around the stacks, we also check spine conditions and sequencing to make sure the books are labelled and ordered correctly. This is all part of caring for a physical collection and making it accessible, something we really pride ourselves on. But it’s just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the Templeman’s collections – which encompass a plethora of digital resources and unique special collections and archives (SC&A).

Last year, I did some job shadowing with the SC&A team, who were – as ever – incredibly generous with their time and expertise. It was quite the whirlwind adventure, and offered fresh perspectives into collection management and engagement. Over several weeks, I observed and assisted with different activities and processes which, together, gave me an overview of how items are accessioned, catalogued, and used for teaching and outreach.

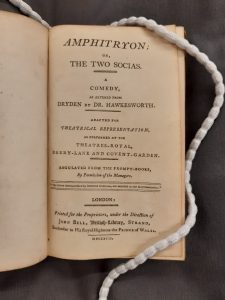

My first day was spent in what felt like familiar territory, assisting Jo Baines with processing the miscellaneous books collection. As you might expect, the Templeman extension had required several stock moves, and this collection was now ready to be re-homed in SC&A’s basement store. However, this was quite different to the stock moves I was used to, since the biggest challenges in main collection are to move the books as quietly and expediently as possible, whilst spacing them appropriately to accommodate new and returning stock. In an archive setting, the process was at once slower and more exhilarating. The books had been wrapped in conservation-grade tissue paper, and stored in numbered crates with accompanying stock lists. Before they could be moved to a new shelf location, we had to assess their condition and conduct a stock check – unpacking, unwrapping, identifying and organising each item by turn. We had to check title pages and be alert to signs of mould. Whilst laborious, I was struck over and over by the sheer joy of handling rare books, particularly when I discovered items pertinent to my own research! Not only did I improve my object-handling skills, but I even came face to face with one of my eighteenth-century role models.

I stumbled across these plays purely by chance, and this was a reminder of how simple curiosity can pay off. Since working for LE gives me essentially VIP access, I am well used to the benefits of shelf-browsing; this exercise in SC&A just made me realise how challenging it can be to make archive material accessible. Special collections are, as the name indicates, special – specific conditions must be met for storing and handling them. Their searchability therefore relies greatly on the digital, and it is the cataloguer’s task to extract meaningful data from each object so that it can be reliably represented on a virtual platform.

I spent some of my job shadowing observing University Archivist Tom Kennett and Metadata Library Assistant Jennie-Claire Crate as they respectively catalogued the University of Kent’s archive and the Max Tyler book collection. These are huge projects, and I only observed a fraction of their work, but found it fascinating. Jennie was working on a database I was familiar with, the software behind LibrarySearch. Depending on the book she was cataloguing, she might find an existing record that could be duplicated or would create one from scratch, deftly translating bibliographic detail into cataloguing code. What struck me was her attention to detail, seeking to capture as much information as would be useful to future researchers. The Max Tyler collection pertains to music hall and vaudeville traditions, and includes material on contemporary performance practices like blackface. Thus, besides cataloguing techniques, this prompted a more general conversation about classification, erasure and racial politics. In the wake of Black Lives Matter I feel again how imperative such conversations are, as they inform more and more of what we do across the Templeman generally to subvert racism and support diversity. Everything is political.

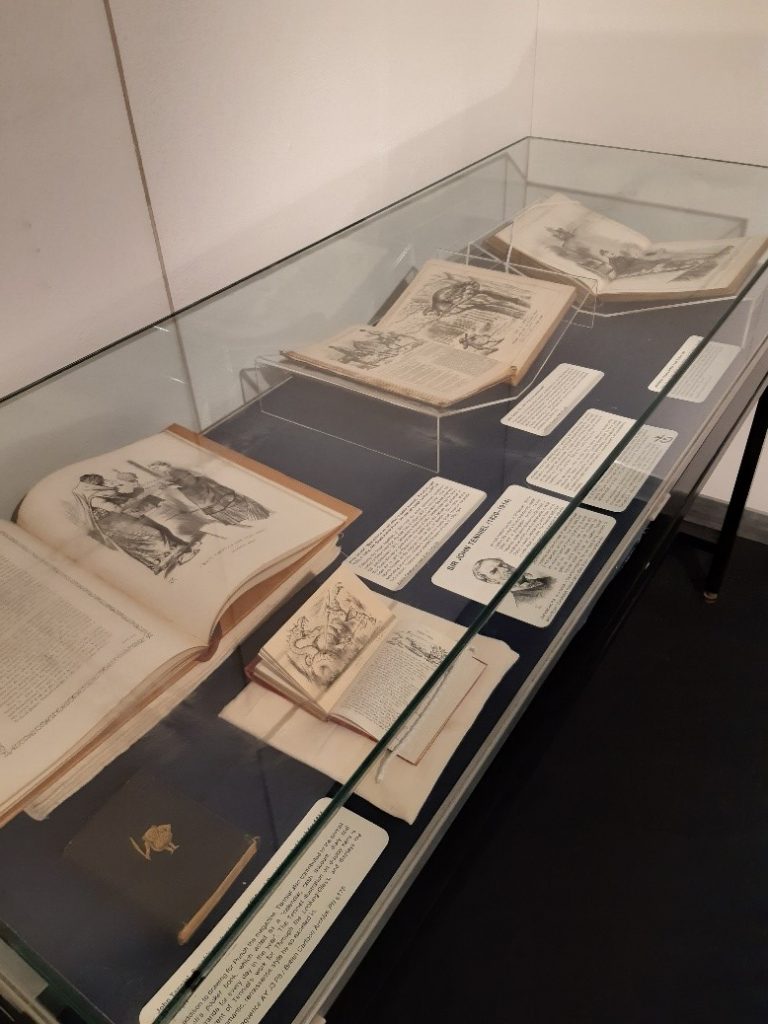

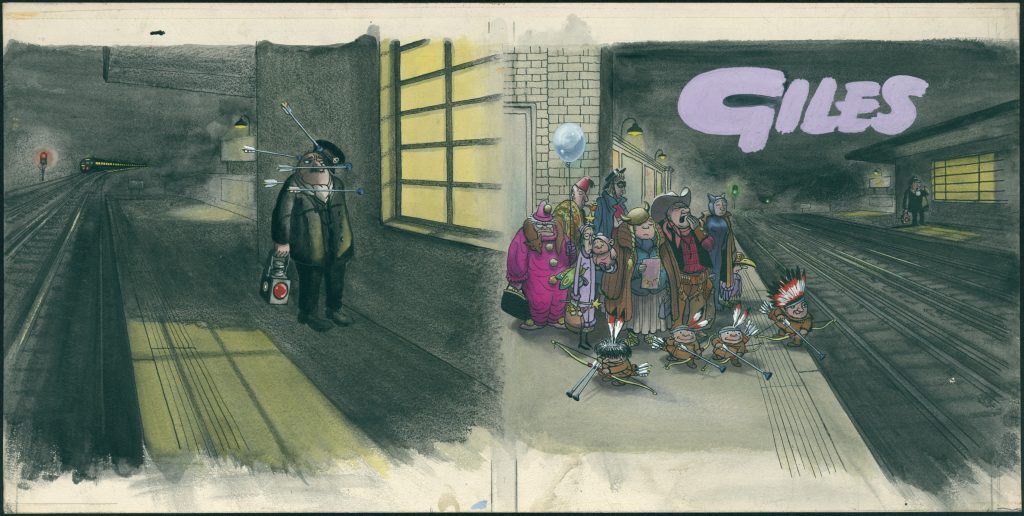

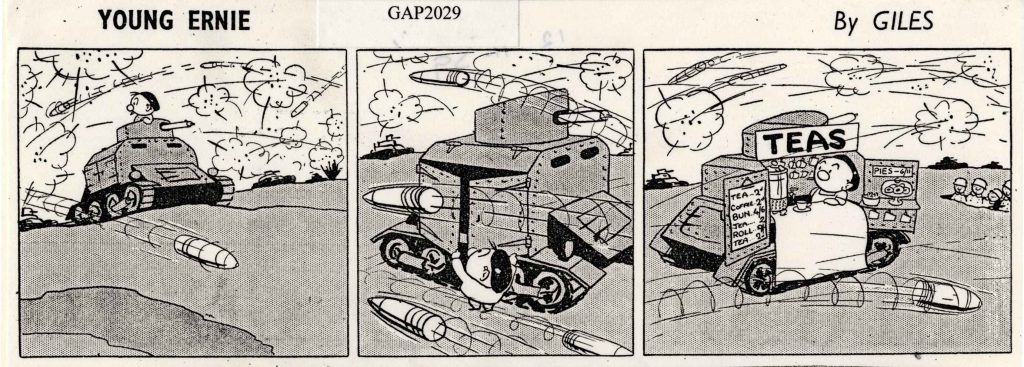

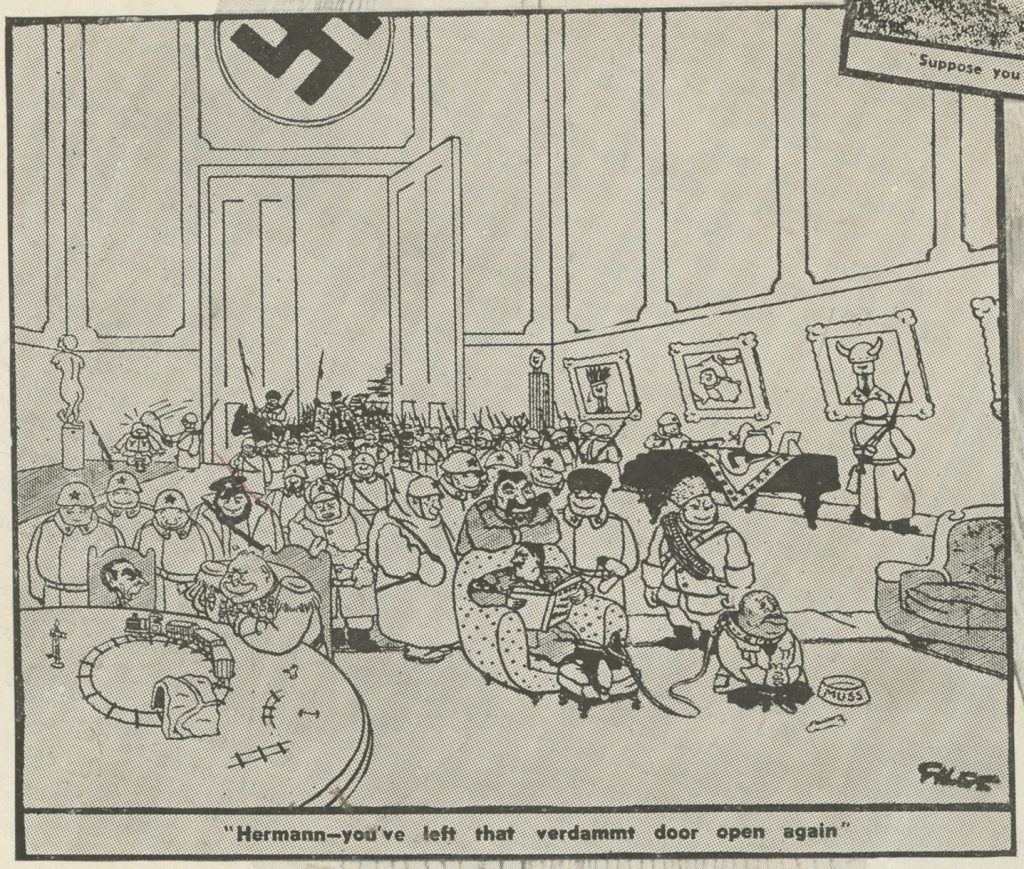

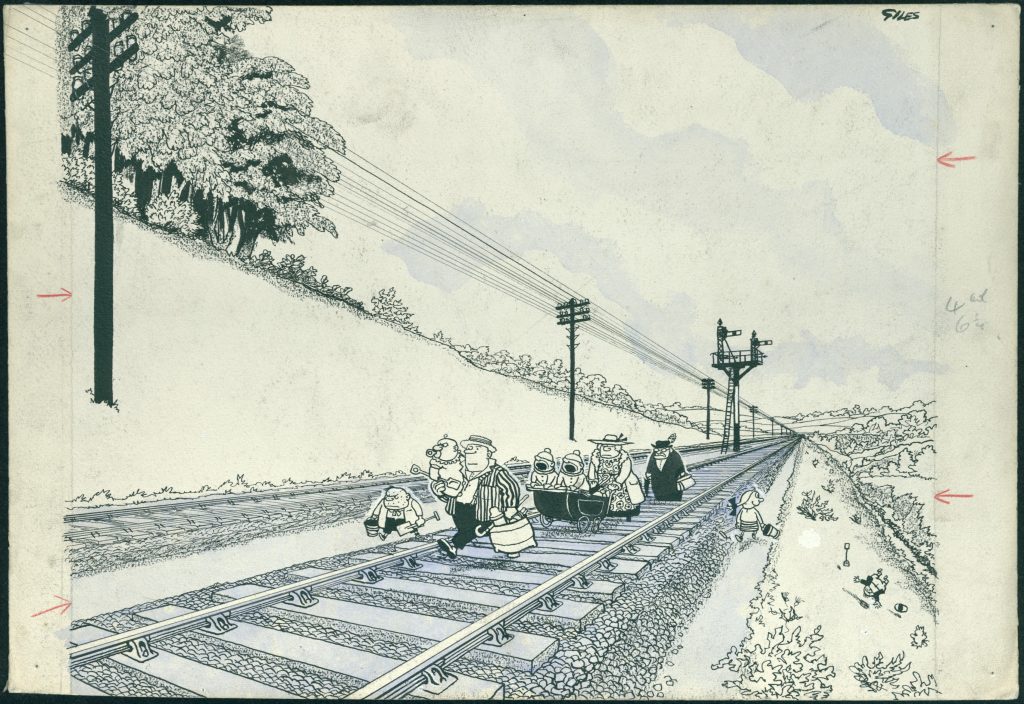

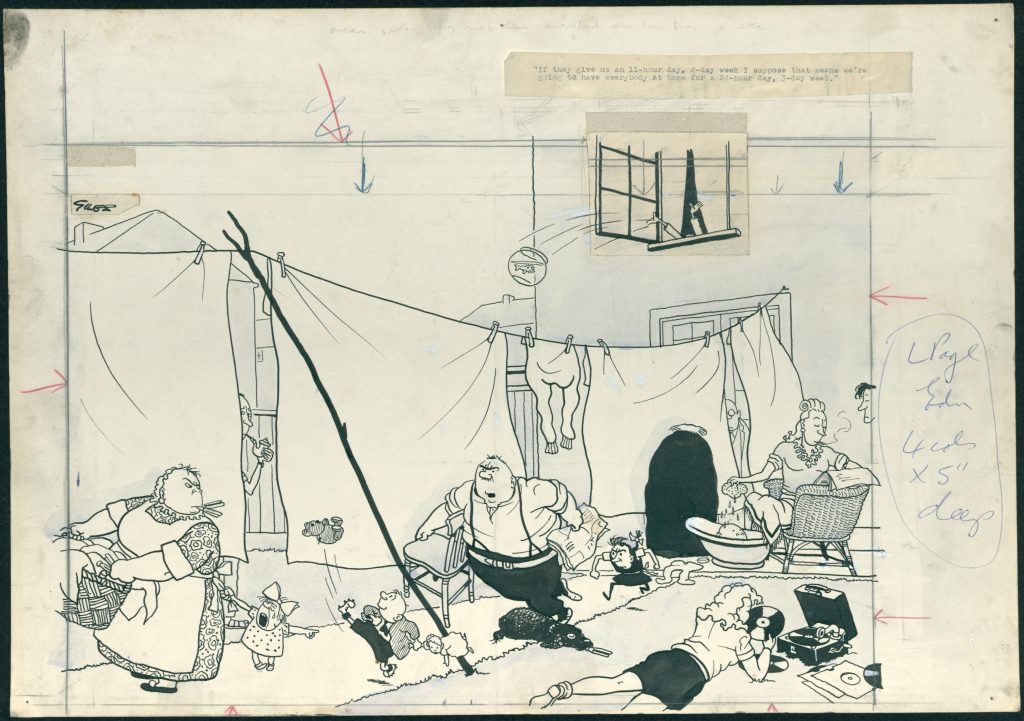

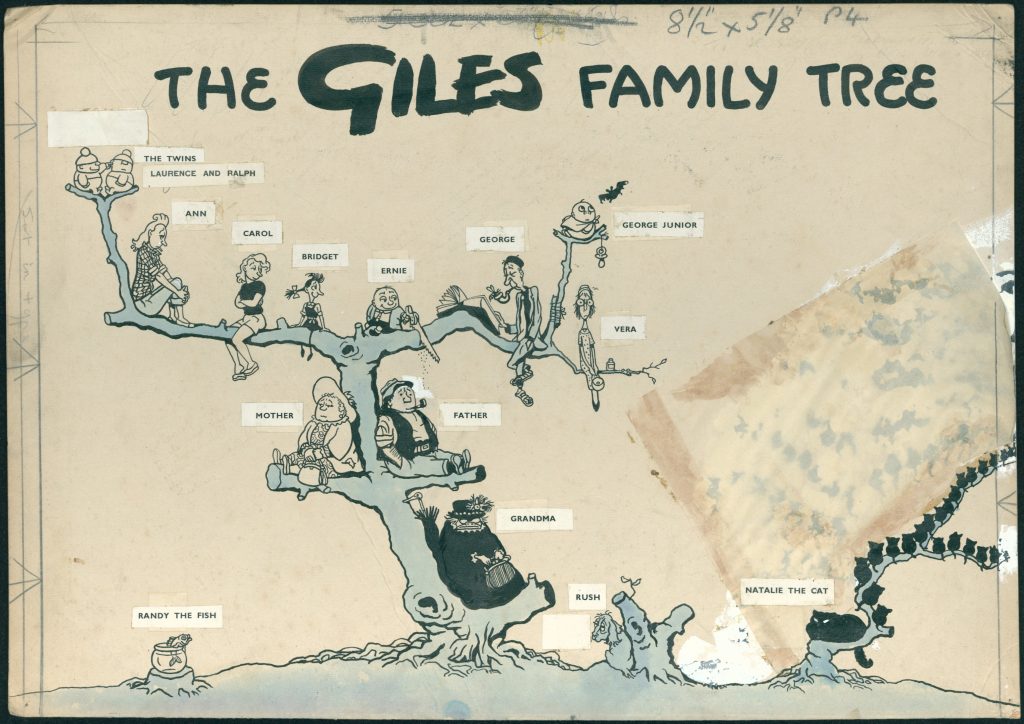

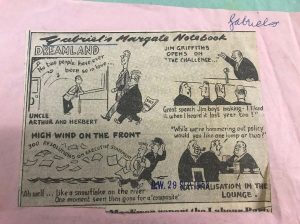

One of SC&A’s collection strengths is, in fact, political cartoons, and these formed the basis of a recent exhibition in the Templeman, dedicated to John Tenniel and the enduring influence of his Alice in Wonderland illustrations. Curated by Tom and Jo, I was able to help with the physical installation, taking down the preceding exhibition, and subsequently retrieving and arranging the new material. I took before and after shots of the process, which was naturally hands-on and organic, but not without its challenges! With objects that are so varied in themselves, each one has to be considered both on its own and in conjunction with others to create a visually appealing and cohesive narrative. And, of course, they have to work in the assigned space. Tom and Jo had already short-listed items, thought of a thematic structure, and done an extraordinary amount of research for the accompanying captions. The table-top cabinet (pictured below) served as a space to introduce Tenniel as a political cartoonist, whilst three wall cabinets show-cased political work by later artists inspired, respectively, by the Cheshire Cat, the Mad Hatter’s tea party, and the Tweedle-twins. It wasn’t until we could handle the material and position it in the cabinets, however, that we could make final judgment calls on what worked – a sort of three-dimensional edit. I found this experience particularly rewarding and it taught me a lot of the practical skills needed in preparing objects for display. We had to make bespoke arrangements to support different media types, using cushions, snakes, Perspex book rests, command strips, transparencies and acid-free card, the latter cut to size to suit newspaper cuttings, facsimiles, and original art works. So it was, you might say, quite the vocabulary lesson too!

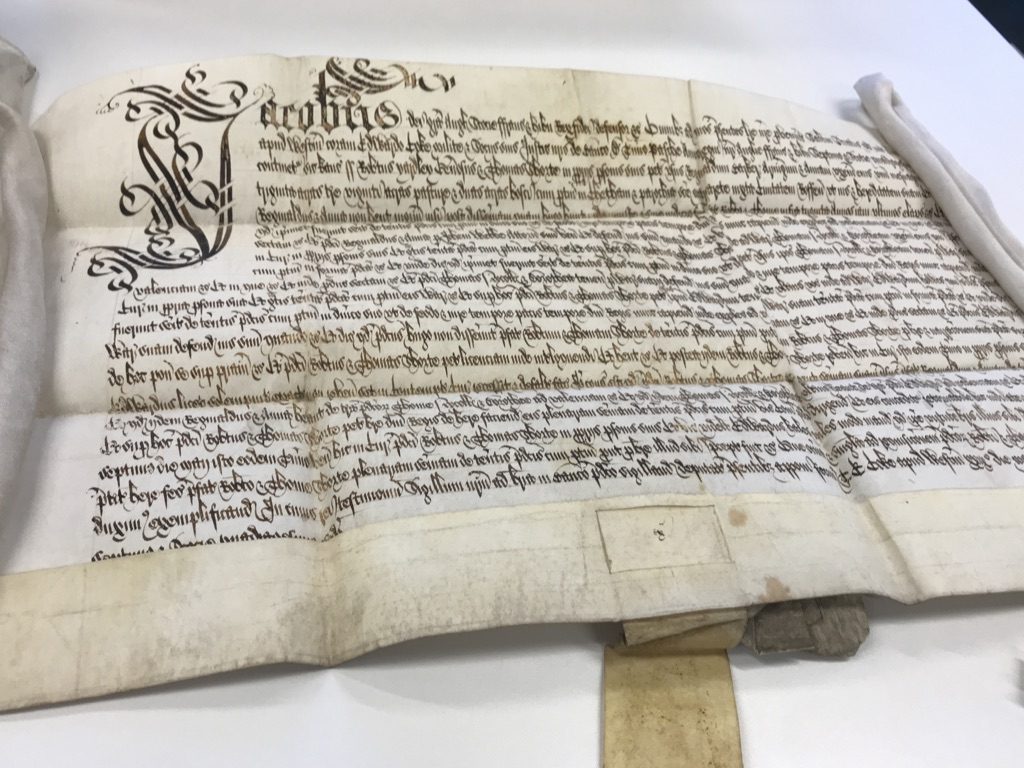

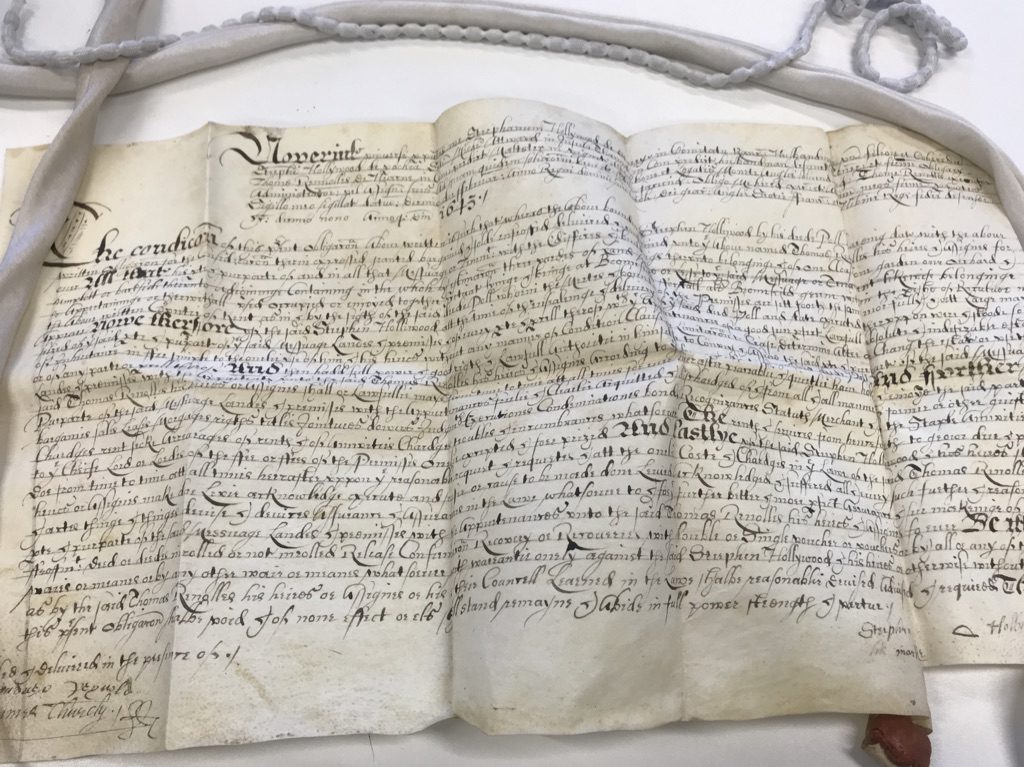

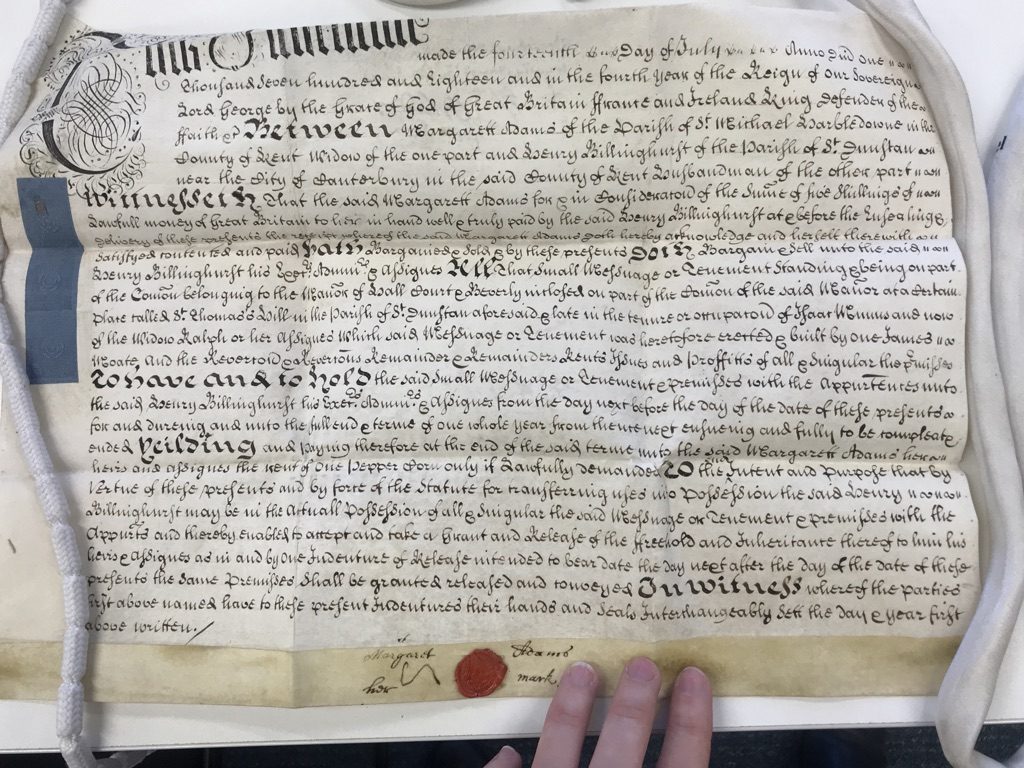

Whilst exhibitions form a principal part of SC&A’s outreach, and greatly contribute to the cultural life of the Templeman, I also learned more about their other engagement activities, helping Jo run a seminar with a local secondary school group. SC&A have strong links with the University’s academic schools and Partnership Development Office, and would (prior to the pandemic) regularly run these sessions from their reading room (a service they will surely revive as soon as it is safe to do so). Jo designed this particular session around the pupils’ curricular interest in the War of the Roses, selecting material to show how this historical event had been recorded and adapted from early modern times to the present. This was, for many of the pupils, their first visit to an archive; perusing early texts like Holinshed’s Chronicles therefore prompted conversation not only about Plantagenets, but about printing and book history itself. We were greatly helped by staff and students from the Schools of History and European Culture and Languages, and it was great to witness the pupils’ growing confidence over the course of the session, consolidated, rather colourfully, on handy post-its.

Looking back, I really had some fantastic experiences with SC&A which helped build collegiality and strengthened my understanding of our different services and resources. I have always been an advocate of job-shadowing and cross-team working, and my thanks go to the whole team for making me welcome.