On the evening of 6th October I, and other members of Kent’s Library team, had the opportunity to present a small exhibition at the Canterbury Cathedral Open Evening. This year’s theme was ‘The Role of Women Through the Ages in the Life of Canterbury Cathedral’, and as the holders of the Hewlett Johnson Papers, we thought we could provide an insight into the life of his second wife, Nowell Johnson.

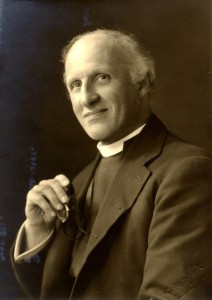

Hewlett Johnson was born in 1874, and married his first wife Mary in 1903. She died of cancer, and the couple had no children. He became the Dean of Canterbury Cathedral in 1931, and remained so until 1963. This was a hugely interesting time for the whole world, as his time as Dean coincided with the Second World War and the advent of Communism, and the Soviet Union in particular. He was commonly known as ‘the Red Dean’ for his championing of Communism, and for a time was highly influential. However when the Soviet Union fell out of favour with the rest of the world, Johnson’s influence waned, although his faith in Communism never did.

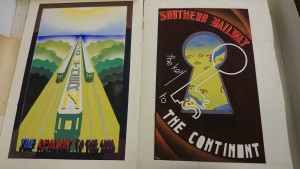

He married Nowell Johnson, the daughter of a vicar and 32 years his junior, in 1938, on the eve of the Second World War. This caused something of a scandal, as it was commonly believed that she was his niece. In fact, she was the child of Hewlett’s cousin, but referred to him as ‘Uncle’ in order to avoid explaining their complicated relationship. She had been a frequent visitor to the Deanery long before they became romantically entangled, and as she worked as an artist she painted his portrait and provided illustrations for some of Hewlett’s works.

The couple’s first daughter was born in 1940, and the small family moved to a house in Charing, Kent, but quickly realised this was no safer than Canterbury from German bombing raids. Hewlett sent Nowell and the baby Kezia to Wales, where they remained for the duration of the war, and where the couple’s second daughter Keren was born in 1942. Whilst Nowell was in London and Hewlett still on duty at the Deanery the couple wrote to each other almost every day, and many of their letters are held here at the University of Kent.

Life in Canterbury during the war was perilous. 10,445 bombs were dropped on the city throughout the Second World War, and in 1940 one of these hit the Deanery. Hewlett escaped, but apparently narrowly, and telegraphed his wife immediately to let her know what happened. In her replying letter she writes:

“How awful this news is of your narrow escape & the poor old Deanery. It was awfully good of you to have wired for I saw a notice of it in the Times & should have been very anxious. Today there’s quite a bit in the Mirror. I’m awfully glad the damage in the house isn’t as bad as it might have been, what is left I wonder? Are the kitchens alright. & is Mrs County cooking for you still. I don’t like thinking of you alone in Elsie’s room Darling, is the building safe?”

She adds: “What savage attacks they have made on the Cathedral, its [sic] amazing they haven’t hit it as yet, but one fears much they will go on. Could you not sleep in the crypt now?”

The Deanery did sustain some damage, but ultimately survived. The reality was that hundreds of homes were completely destroyed in the heavy bombing on Canterbury, and in comparison the Deanery got off lightly. However, Nowell’s words were to prove prophetic. In 1942 the Cathedral was finally hit, as a bomb fell directly on the Library:

“Its terribly terribly sad to think of Canterbury now – in June too when it used to be so peaceful & so gay. I’m sure the people are splendid, its wonderful how grand people are in great trouble. I’m very glad you made the B.B.C. after their talk, has more of the Cathedral than the library been damaged? Were all the valuable books got away.”

The rare book cataloguer in me is very pleased to see she lends a proper amount of concern for the contents of the Cathedral library, as well as the praise she heaps on the people of Canterbury for bearing up in the hugely difficult circumstances they found themselves in. Indeed, Nowell was not only concerned for the people in Britain. Another letter from 1940 reads:

“Poor little mites in Canterbury – & Cologne – & cities all over the world. What a ghastly time, what utter utter madness, how long can it go on. Poor Canterbury, what has happened to it, there will be many casualties I fear, I long to hear from you. And the beautiful Cathedral, is it safe? And the Deanery, I still think of it as it used to be”

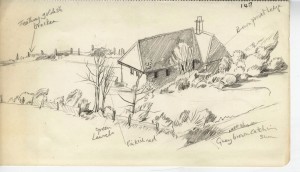

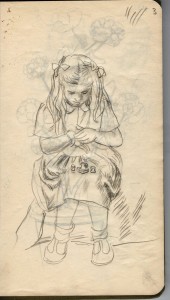

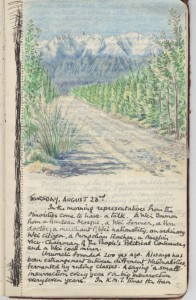

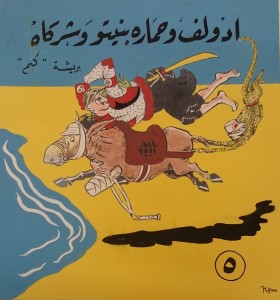

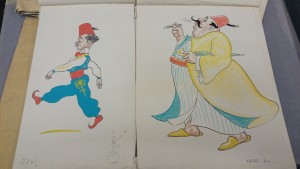

When the war came to an end the family we reunited in Canterbury. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s the family traveled a great deal, particularly around the Soviet Union, Cuba and China, two famously communist countries. They also visit many parts of the UK, Hungary and East Germany. They took large numbers of photographs, now held here at Kent, and Nowell kept travel diaries. Here her artistic flare is clearly visible; the diaries are full of small doodles, and full page drawings, of things she saw during her travels.

On her visit to Hungary in 1951, she recorded visiting a Worker’s Rest Home, “where workers from all kinds of employment go for a fortnight’s holiday,” where her husband was “given a tremendous reception.” She also talks of visiting an International Rest Home, “a truly magnificent place, like a great first class hotel,” with “great international flags hung by the entrance,” where they were greeted by a delegation from Czechoslovakia, and given flowers by a child.

The following pictures were all drawn during her time in Hungary, and represent the huge variety of subject matter in her diaries.

The family traveled around China on many occasions, and numerous diaries survive documenting their trips. A diary entry from their 1964 trip records how:

“There are attendants everywhere, girls & boys they seem, who do everything for us. They are most competent & so gentle, helping Hewlett to dress etc. One boy is always at his side seeing he does not trip or stumble…Again Mr. Huang Shiang tells us how concerned the Prime Minister is that we should be comfortable, & also that because of this & because he wants us to see all that we wish he is sending a special plane that will make it easy to get about.”

These attentions must have been particularly pleasing to Nowell, as her husband was 90 year old during this trip, which cannot have been easy.

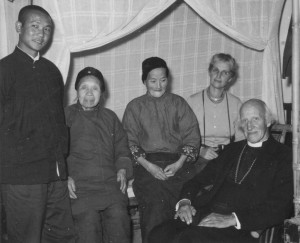

Wherever they went, the Johnsons tasted what life was truly like for people in these countries. As these photos show, they visited regular people, and the variety of people they met must have been fascinating to experience. It’s certainly fascinating to see the photos decades later.

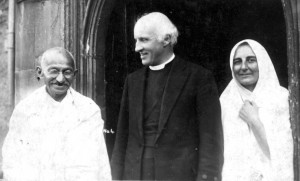

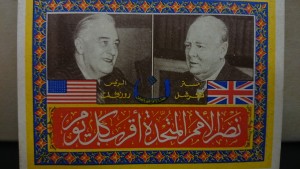

During the Johnson’s time at the Deanery they entertained many important and intriguing visitors. Such guests included Russian diplomats, Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of Franklin D. Roosevelt, President of the USA during the first part of the Second World War, British Royalty and even Gandhi. Here are a few photos from these occasions:

People’s reactions to our display at the Cathedral were hugely positive. We had several people looking at the display who remembered the family. A couple went to school with the Johnson’s daughters, some others remembered seeing the Dean walking from his temporary housing in St. Dunstan’s after the bombing of the Deanery to the Cathedral for his work. There was one woman who deliberately sought out our exhibition, who used to visit with Nowell. She remembered all the negativity surrounding the family because of the Dean’s politics, but proudly reassured us her family took no part in this negativity. Nowell attended Age Concern art classes with her after the Dean’s death. The woman told us of a postcard she had from Nowell when she went to a conference in Scandinavia, and how Nowell encouraged her to keep on with the art classes, as they were so beneficial to the community.

Meeting people who remembered the family and who could tell us stories that we never knew about was fascinating. That our small display brought such happy remembrances to the lady who ran the art classes was incredibly rewarding, and preserving this history for other people to enjoy is what this job is all about.

Rachel.