You might have noticed that we were closed for much of last week; if you’ve wandered past the door to the reading room between last Tuesday and Thursday, you might have seen the sign on the door saying that we reopened on Friday morning. This closure was so that the team could focus on starting on two Preservation Assessment Surveys, which will guage the level of care needed in the future to maintain our collections.

The Preservation Assessment Survey was created and is administered by the British Library, which provides the tools for the job, plus endless expertise, encouragement and support. The idea behind the survey (and based on complicated equations) is that a reasonably random sample of around 400 items in a collection can give a snapshot into the preservation needs and state of a collection. Once the statistics have been gathered, the Preservation Assessment Survey team take the data and create a report highlighting issues which need to be addressed.

For our surveys, we also asked to include a measure of whether items were ready to be moved into the new basement store which will be opening with the Templeman extension. This will give us a really good idea of the work which we need to get done in the next couple of years, as well as the next few decades.

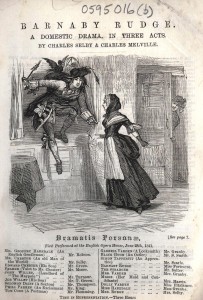

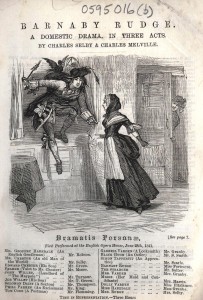

Script of Barnaby Rudge by Charles Selby, 1841

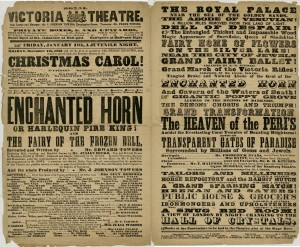

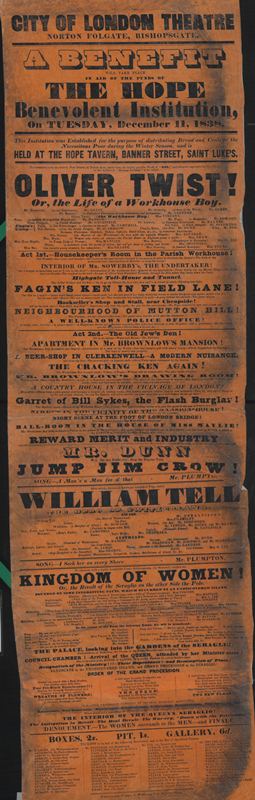

Because our collections are quite diverse, we decided to do one survey for our books and bound items, and another for our archival items. Of course, this wasn’t quite as straightforward as it sounds. We spent some time trying to decide whether published play scripts counted as books and unpublished play manuscripts are archival (answer, for the purposes of this survey: yes), which survey maps should come under (answer: books) and then classifying shelves as archival or book so that we could get our full sample! Thankfully, with help from Julia Foster of the Preservation Assessment Centre, we got the sampling done in just a day and made a start on the survey itself last week.

For each of these 800 items (two surveys of 400 items each, if you were wondering) we have to answer 15 questions on preservation, which include considerations of environment,usage levels and whether or not the item needs boxing. There is then a further set of questions, which detail the condition of the item and whether it has been damaged (by pests, dirt, poor handling etc.). As you can imagine, this provides a pretty comprehensive set of requirements for each of the items, and requires some consistency in answers, since the assessment of damage is quite subjective, and depends on the state of the last item you saw!

It took us a day or so to find our rhythm, working in two teams to start off our survey in the Special Collections Store and the British Cartoon Archive Store respctively. Archives, it turns out, take far longer to survey than books, since they have to be removed from (and returned to) boxes, and the questions take a little more imagination to answer than they do for bound items with titlepages. By the end of the first full day, we were proud to have completed surveying 60 archival objects and 47 books! (In fairness, those 47 books represented to total input of bound items from the British Cartoon Archive, which was quite an achievement).

By the end of the second full day, we had completed around 160 books and a similar number of archival items. Having started intesively, we’re now going to be carrying out the odd hour or so of surveying here and there (without closing the reading room!) to keep up the momentum until the closure of the data gathering section of this project, which should be around the end of August. Then, with our full set of 800 results, we’ll send the information off to Julia at British Library and await the report with great anticiptation.

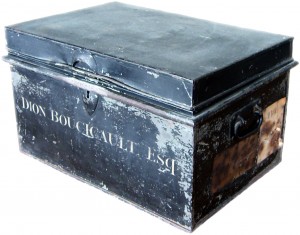

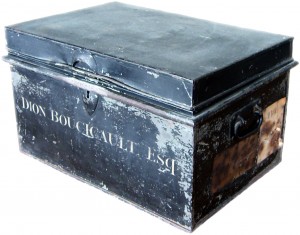

Bouciault’s deed box forms part of the collections

It really has been an interesting process so far (and we’re not even halfway through!) For one thing, it puts the size of collections into perspective. We ended up sampling just one item from the combined Fawkes and Calthrop Boucicault Collections, which makes up one of only two major collections on the Victorian playwright in the world. In comparison, we sampled several items in our Wind and Watermills Collections, which are used less intensively, perhaps due to the fact that the photographs can all be viewed online.

It has also been great to get to know the book collection slightly better. We still have a fair way to go, but already we’ve picked out some wonderful and occasioanlly eccentric items, amidst the rare editions and the early printed books. One particularly interesting section in our collection is about dialect; as Steve and I were going through the books, we came across a two volume set on The Craven Dialect (London, 1828), an area in North Yorkshire, which seems to have a lot of words specific to cows and their illnesses! Not much further on, I came across a book on Kentish Dialect by Parish and Shaw (Lewes 1888) which ranged from words which are now very familiar:

Blunder (vb) To move awkwardly and noisily about

to the very unfamiliar:

Mabbled (vb) Mixed; confused

This Kentish dialect dictionary has been interleaved with blank pages on the right hand side (recto), on which at some point someone has jotted down their own dialect discoveries, with their meanings, from time to time. It all goes to much our language has changed, even over just 100 years.

I’m sure that we’ll make many more discoveries as we carry on with the survey, which will, in the end, give us a much better understanding of our collections as a whole, and their needs. So thank you for your patience during those closure days; it really was helpful to get a chunk of the survey under our collective belt!

And I’ll let you know how it goes…(with running updates on Twitter – @UoKSpecialColls).

To celebrate this anniversary, there will be a half day symposium will be held at the Cathedral on Saturday the 17 August from 10am-1pm. During the symposium, an exhibition, including many of the items which featured in ‘Picture This’, will be launched. It will be open to the public from 19 – 30 August from 2-4pm. For more information about both of these events, and the series of features, take a look at the Cathedral’s webpages.

To celebrate this anniversary, there will be a half day symposium will be held at the Cathedral on Saturday the 17 August from 10am-1pm. During the symposium, an exhibition, including many of the items which featured in ‘Picture This’, will be launched. It will be open to the public from 19 – 30 August from 2-4pm. For more information about both of these events, and the series of features, take a look at the Cathedral’s webpages.