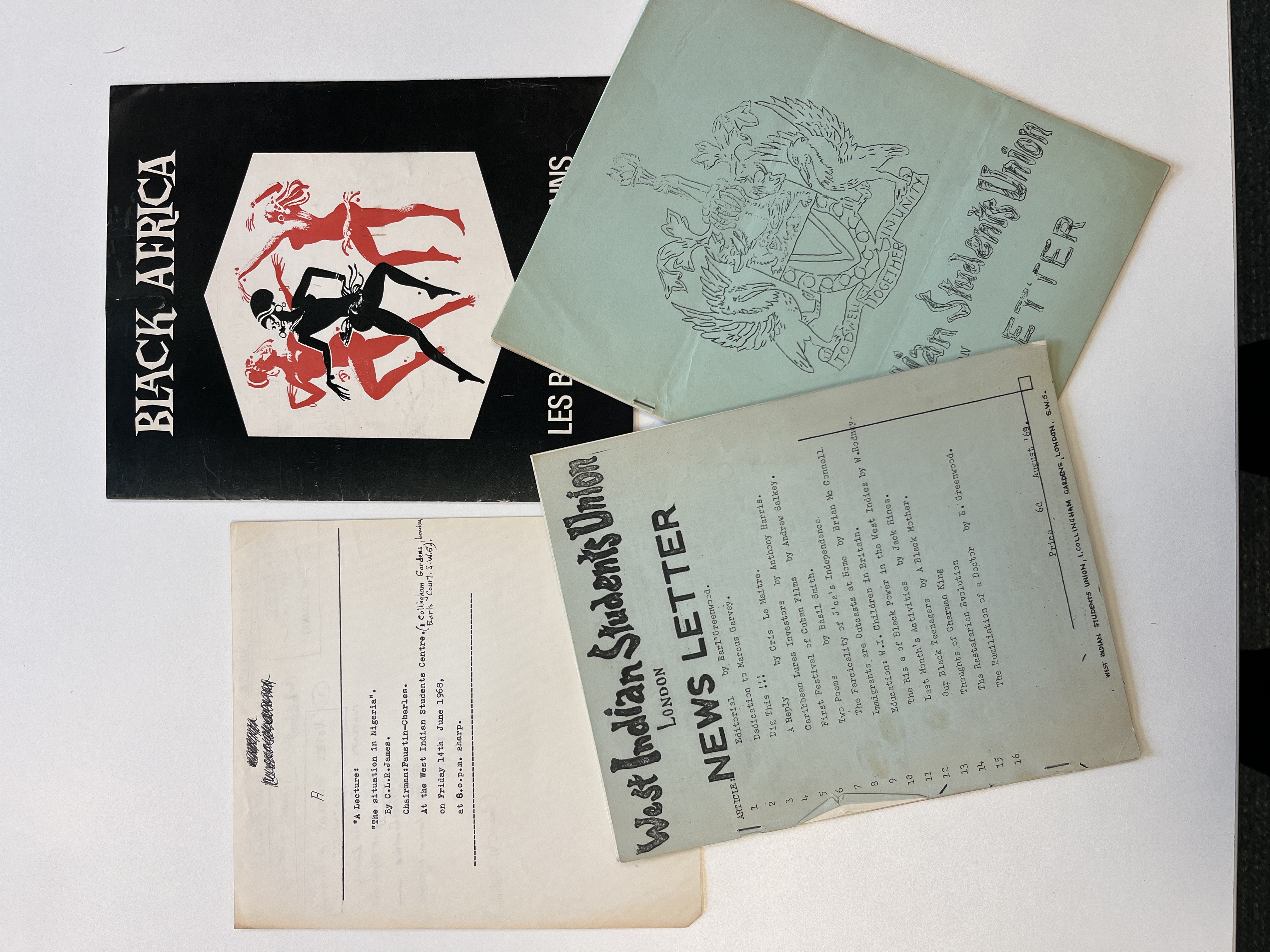

This blog, by Rhodri Davies, Pears Fellow at the Centre for Philanthropy, was first published as a series of panels in the Exploring Philanthropy exhibition in 2022 in the Templeman Gallery at the University of Kent. The exhibition featured original items from within Special Collections and Archives to support the exhibition as it explored the history of philanthropy, changing perceptions of philanthropy and how philanthropy is carried out today.

The blog is Illustrated with images from within Special Collections and Archives and elsewhere, and highlights some of the ways in which philanthropy has been parodied and mocked throughout history.

Warning: This blog does contain imagery relating to the trade in enslaved people and the differences of opinion in Great Britain at the time about the focus of philanthropy within Great Britain and overseas. See our note on these items at the end of the blog post.

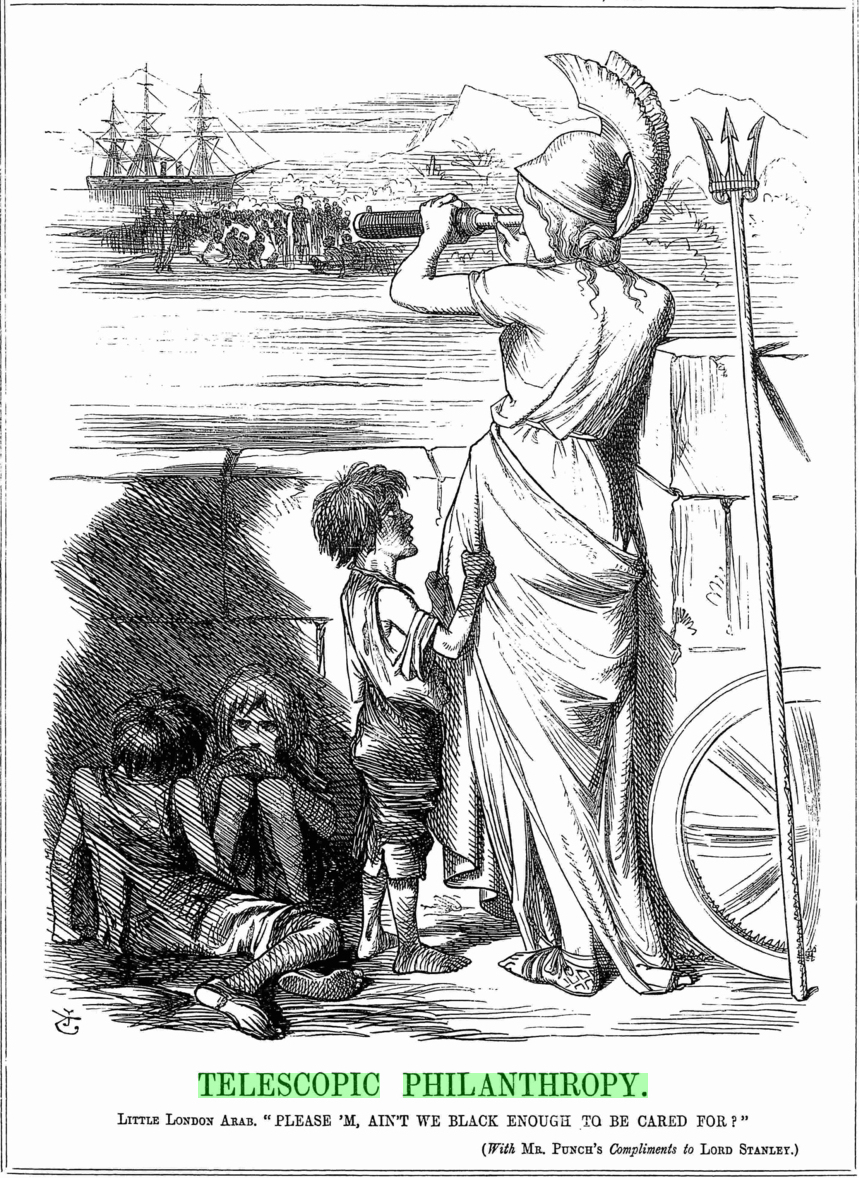

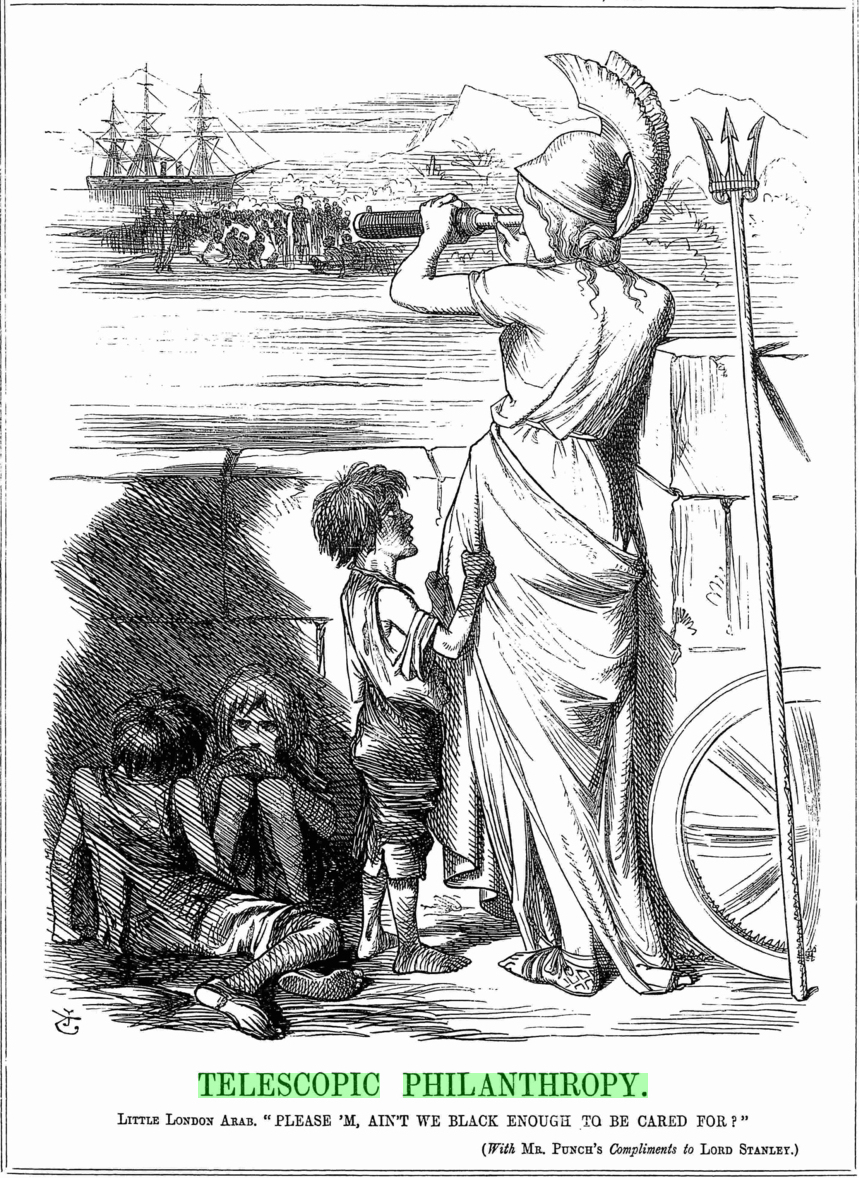

Telescopic Philanthropy

From the mid 18th century until the end of the 19th century, there was a recurring critique of “telescopic philanthropy”. This referred to giving that was seen as focussing on the plight of foreigners living in other countries at the expense of addressing pressing issues of poverty and suffering in the UK.

At first this critique was stoked by fears of the French Revolution, and the threat that its radical ideas posed to existing class hierarchies in Britain. In 1798 George Canning, a fervent anti-Jacobin (who subsequently became the UK’s shortest-serving Prime Minister), published a satirical poem entitled “New Morality” which mockingly contrasting high-minded “French philanthropy” with good honest “British charity”:

“Not she, who sainted Charity her guide,

Of British bounty pours the annual tide:

But FRENCH philanthropy; whose boundless mind

Glows with the general love of all mankind.”

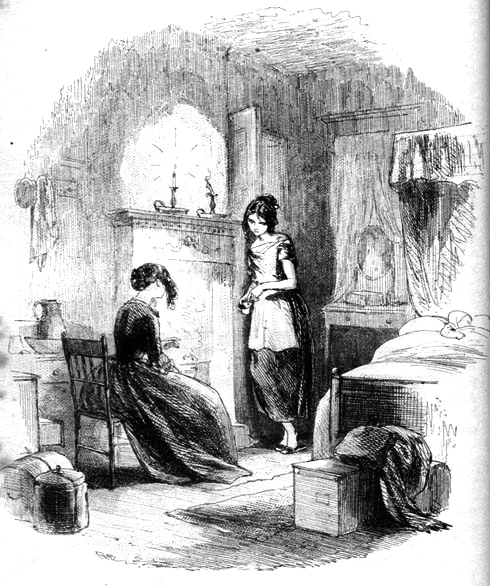

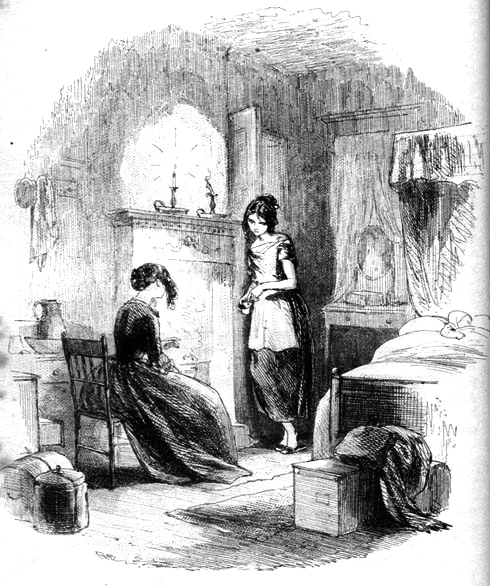

Later Charles Dickens immortalised the stereotype of the telescopic philanthropist in the character of Mrs Jellyby in Bleak House: so concerned with raising money to support the poor inhabitants of “Booribola-Gha” that she neglects her own children to the point that they are destitute.

Miss Jellyby, etching by Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), facing p31 in 1853 edition of Charles Dickens, Bleak House. Image scanned by George P Landow on 6th February 2012. Source: http://www.victorianweb.org/art/illustration/phiz/bleakhouse/3.html

There was often a racial element to critiques of telescopic philanthropy, which were tied into opposition to the abolition of slavery. In 1840, for instance, The Times reprinted a poem from the satirical magazine John Bull which lamented that:

Your thorough-bred philanthropists can glance

Their pitying eyes over Earth’s expanse,

Til sorrow all their bosoms discomposes

For their black brethren sold to whips and chains;

And not a single sympathy remains

For starving whites who die beneath their noses.

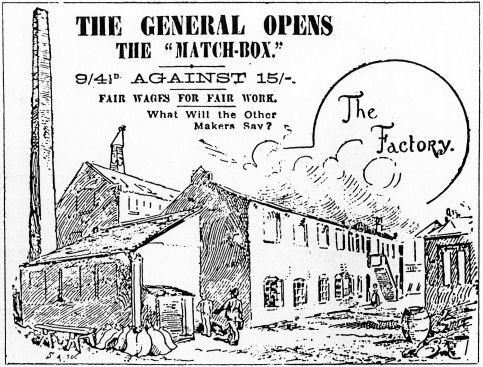

A similar point was captured this Punch cartoon by John Tenniel:

Telescopic Philanthropy – Punch Magazine, March 4th 1865: This engraving by John Tenniel illustrates the concept of ‘Telescopic Philanthropy’ – a phrase partly popularised by Charles Dickens in his description of Mrs Jellyby in Bleak House. In the engraving, Tenniel represents this concept by depicting Britannia with a telescope, her sights fixed on the horizon and the poor and enslaved people overseas, but ignoring the poor children of Great Britain who are pulling at her robes to attract her attention. The subject of the engraving references an argument made by Lord Stanley in Parliament in 1865 to disband the West Coast Africa Squadron. The West Coast Africa Squadron was a naval unit formed to prevent slave trading on the West African coast. Lord Stanley felt that Great Britain should concentrate on their own white neglected poor, rather than the Black poor and enslaved people in Africa. (Caption by Beth Astridge, University Archivist, University of Kent)

Few today talk of “telescopic philanthropy”, but the legacy of these critiques can still be seen in the rhetoric of those use arguments that “charity should begin at home” to criticise international aid and development spending, or to attack the RNLI for saving the lives of migrant people attempting to cross the English Channel.

Mocking the Uncharitable

Those who do not give to charity despite having the means to do so have long been a prime target for satirists.

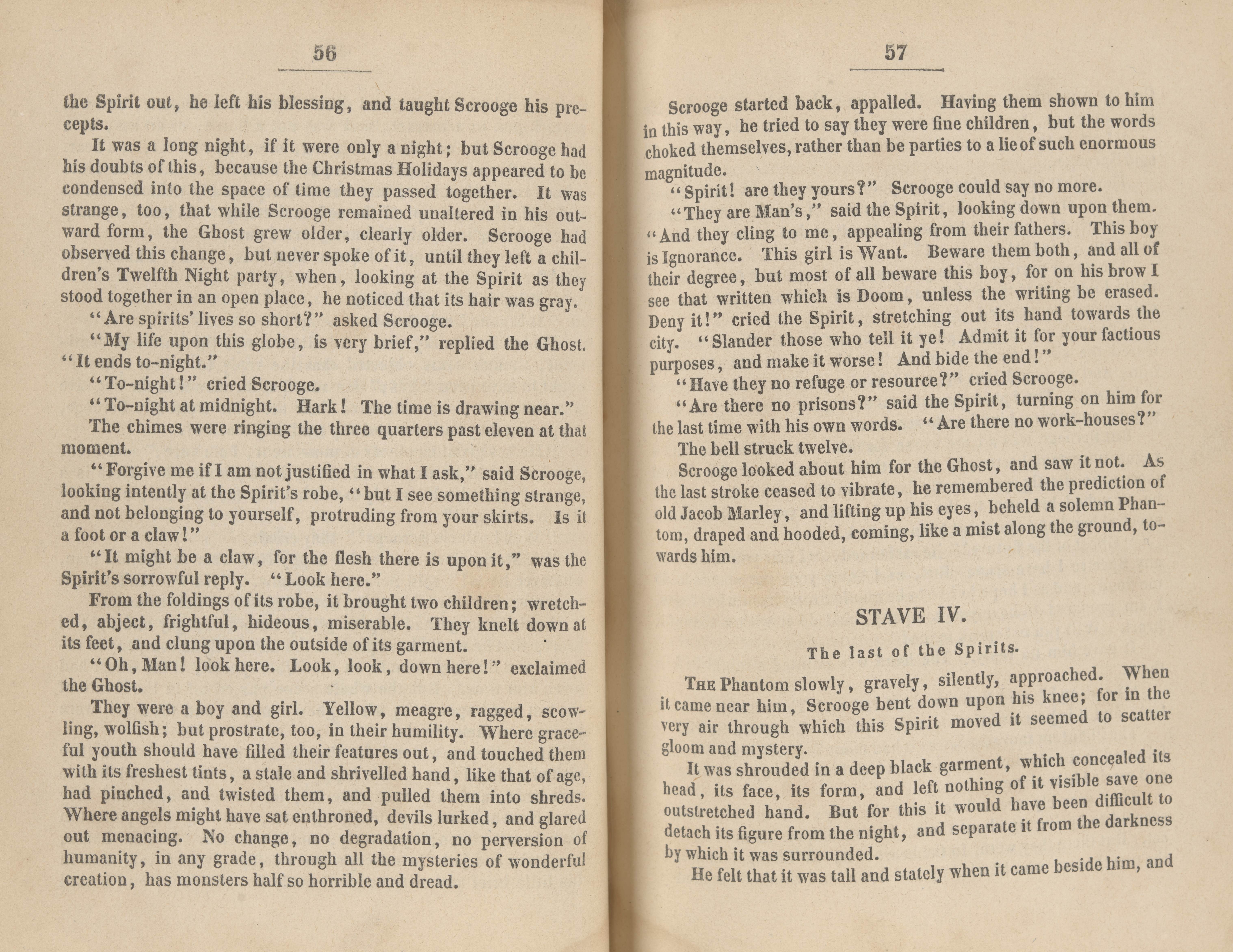

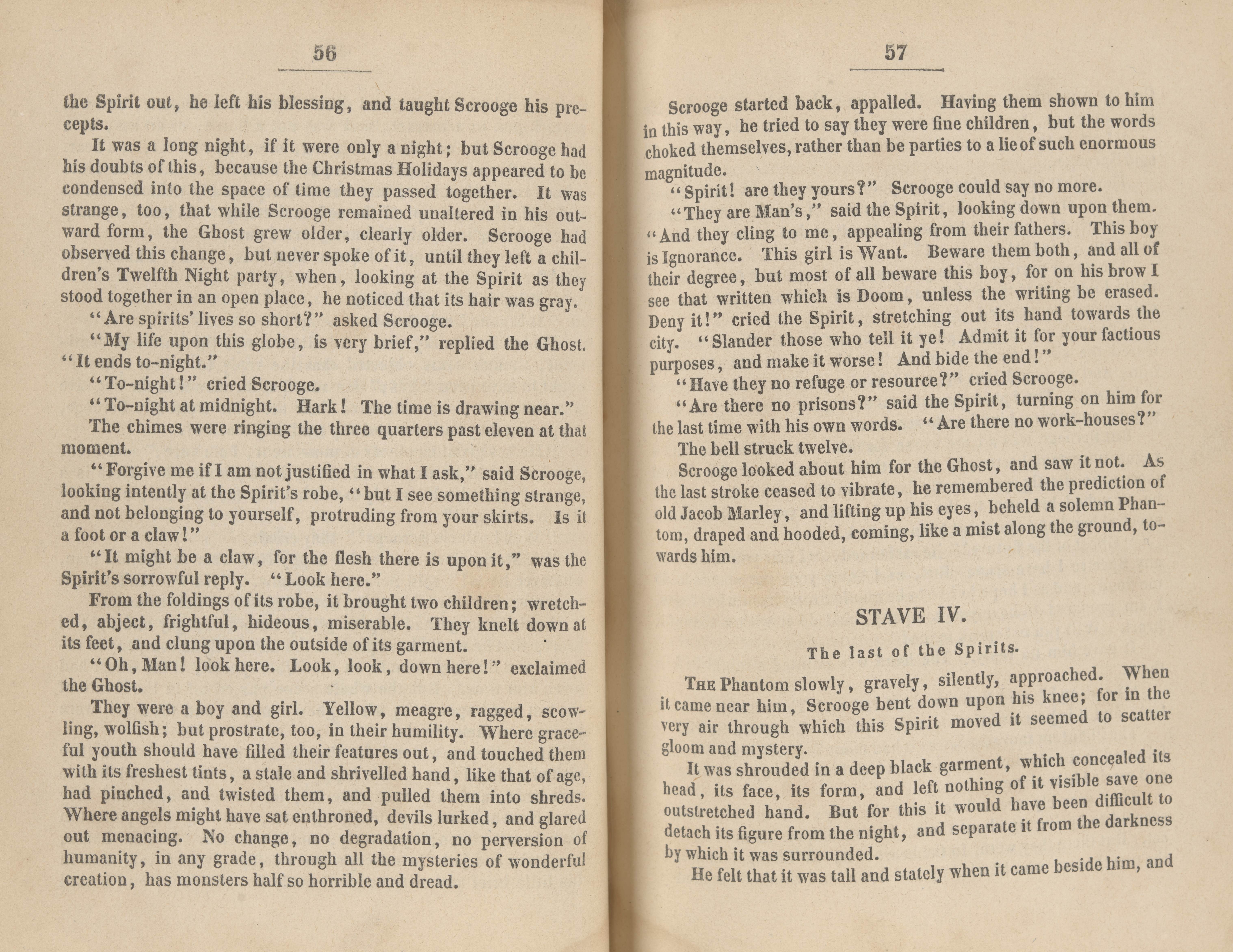

The most famous example is undoubtedly the character of Ebeneezer Scrooge in Charles Dickens’s “A Christmas Carol”. Scrooge’s response when approached by charity collectors about donating to a Christmas fund “to buy the Poor some meat and drink and means of warmth” is to ask “Are there no prisons?… And the Union workhouses- are they still in operation?” He then has these exact words thrown back at him by the Ghost of Christmas Present and eventually sees the error of his ways.

A first edition copy of Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol, (1846) was on display in the Templeman Gallery as part of the exhibition open at page shown here:

Charles Dickens – A Christmas carol in prose; The Chimes, The cricket on the hearth. Leipzig: Bernhard Tauchnitz, 1846. [A Christmas carol is dated 1843]: Charles Dickens (1812-1870) first published his short story as a stand-alone publication in 1843. A Christmas Carol tells the story of Ebenezer Scrooge, a grumpy elderly miser who is visited by the ghost of his former business partner Jacob Marley, and then by ghosts of Christmas Past, Christmas Present and Christmas Yet to Come. The ghosts show him visions of his life and others around him, including his clerk, Bob Cratchit and his poor family. Scrooge learns that joy has little to do with wealth and becomes a different person after his ghostly visitations. Dickens was passionate about social action and this story was inspired by visits to tin mines and a Ragged School where he witnessed society’s treatment of poor children. The story conveys his social concerns about poverty and injustice and enabled this message to be read by a wide audience. Classmark: PD4557.C4 SPEC COLL DICKENS.

[caption written by Beth Astridge, University Archivist, University of Kent]

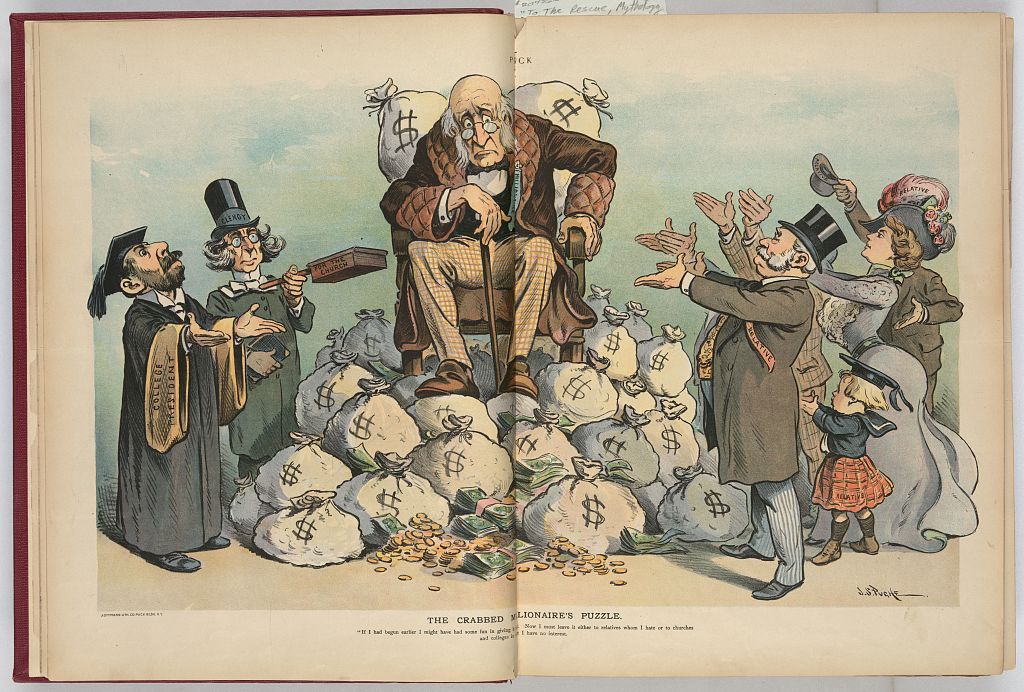

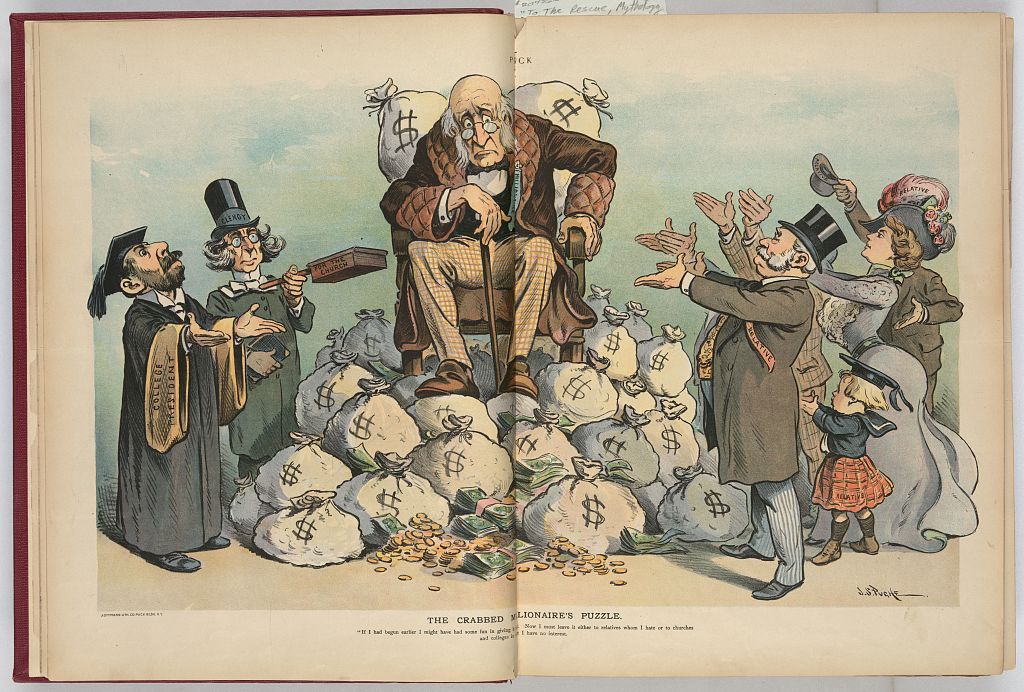

A 1901 cartoon from the American satirical magazine Puck entitled “The Crabbed Millionaire’s Puzzle” makes a similar point about the dangers of miserliness. An elderly and glum-faced Scrooge-like figure sits atop a huge pile of money, surrounded by a crowd of people clearly holding out their hands and asking for donations. The caption reads “If I had begun earlier I might have had some fun in giving it away. Now I must leave it either to relatives whom I hate or to churches and colleges in which I have no interest!”

Pughe, J. S. , Artist. The crabbed millionaire’s puzzle / J.S. Pughe. , 1901. N.Y.: J. Ottmann Lith. Co., Puck Bldg., August 7. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2010651452/.

Making fun of the uncharitable has continued to be a recurring (if occasional) motif in satire. A 1972 sketch for Monty Python’s Flying Circus entitled “The Merchant Banker” saw John Cleese play a caricature of a rapacious capitalist banker. When asked by Michael Palin’s timid charity collector to give a pound, Cleese’s character at first assumes it is a tax dodge. When told that it isn’t, he is unable to understand what is being asked of him, saying “I don’t want to seem stupid but it looks to me as though I’m a pound down on the whole deal…?” The payoff to the sketch is that the banker decides charitable fundraising sounds like a great new way to get money out of people for nothing, and despatches the charity collector through a trapdoor in his office floor.

Whilst we find humour in these characters’ lack of charity and justifications for being miserly, there is perhaps also an element of discomfort; as we are reminded of times that we ourselves have been too caught up in our own affairs to think about helping others, or when we have let cynicism about human nature creep in and become an excuse not to give.

Self Regard and Ego

Those who engage in philanthropy, but are suspected of doing so merely for social status or to burnish their own ego have often been held up for ridicule by satirists.

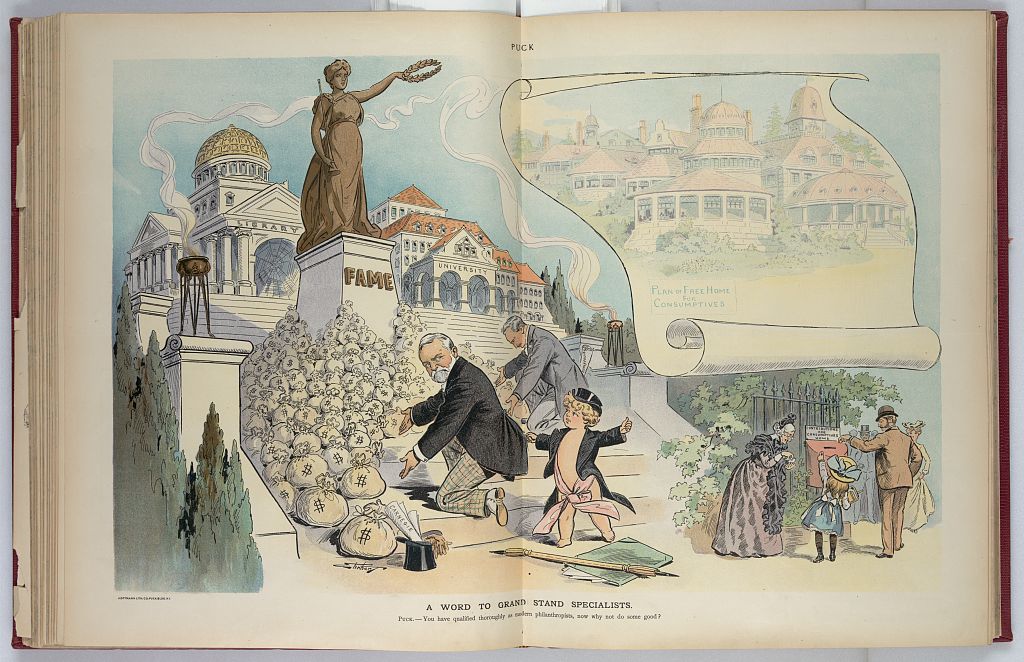

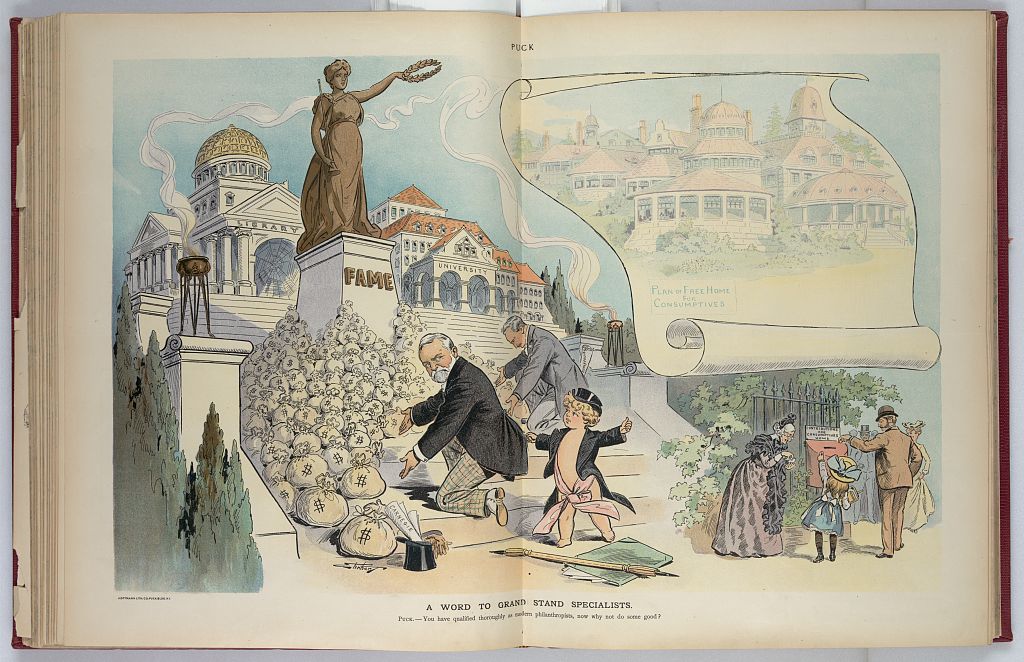

Some of the most famous philanthropists throughout history have found themselves mocked along these lines. A 1903 cartoon for the US satirical magazine Puck, for instance, entitled “A Word to Grand Stand Specialists” , depicts Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller piling bags of money at the base of a statue labelled “fame”, in front of a backdrop of libraries and universities, Meanwhile the impish character of Puck tries to direct their attention towards a home for consumptives and says to them “You have qualified thoroughly as modern philanthropists, now why not do some good?”

Ehrhart, S. D. , Approximately , Artist. A word to grand stand specialists / Ehrhart. , 1903. N.Y.: J. Ottmann Lith. Co., Puck Bldg., June 3. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2010652271/.

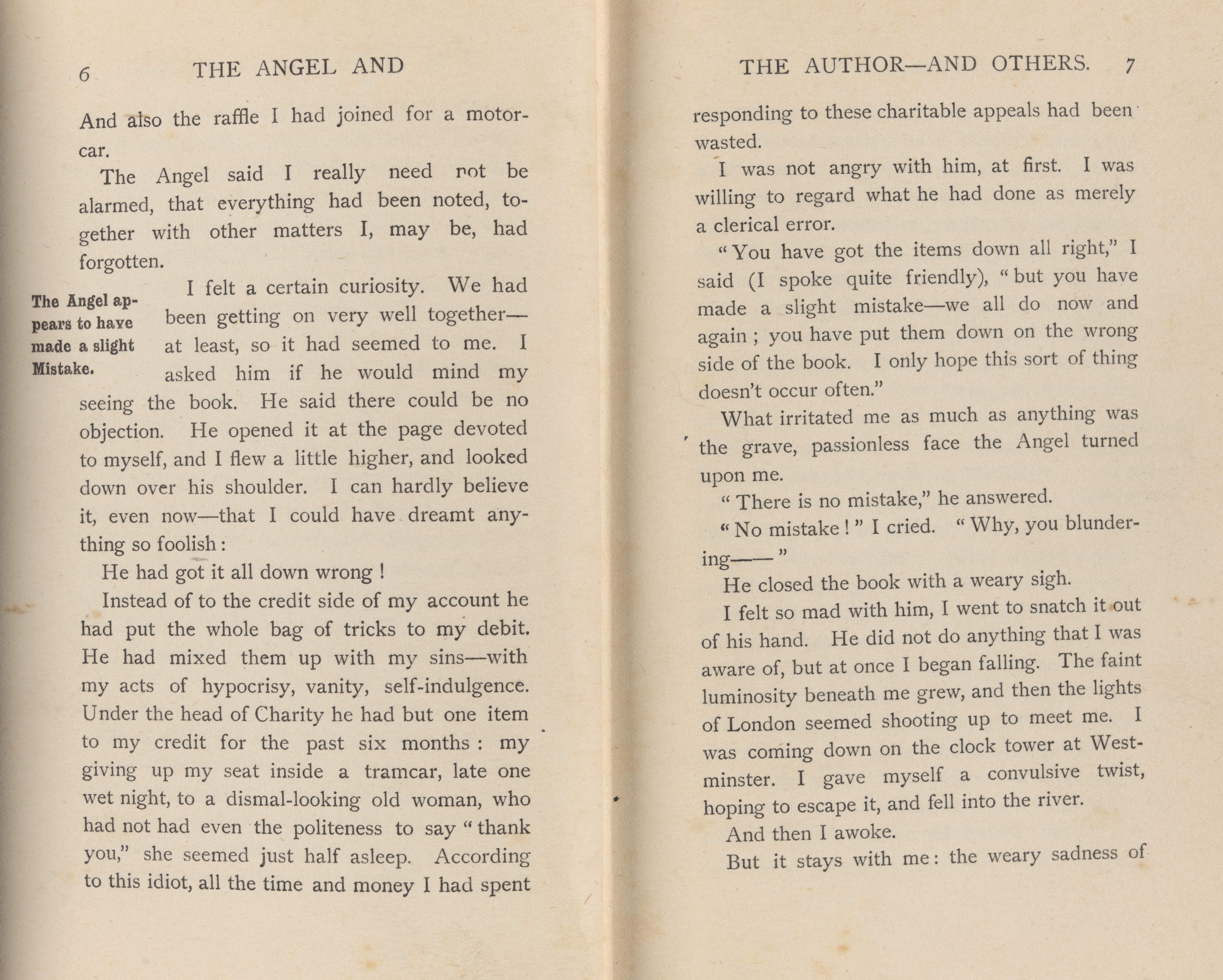

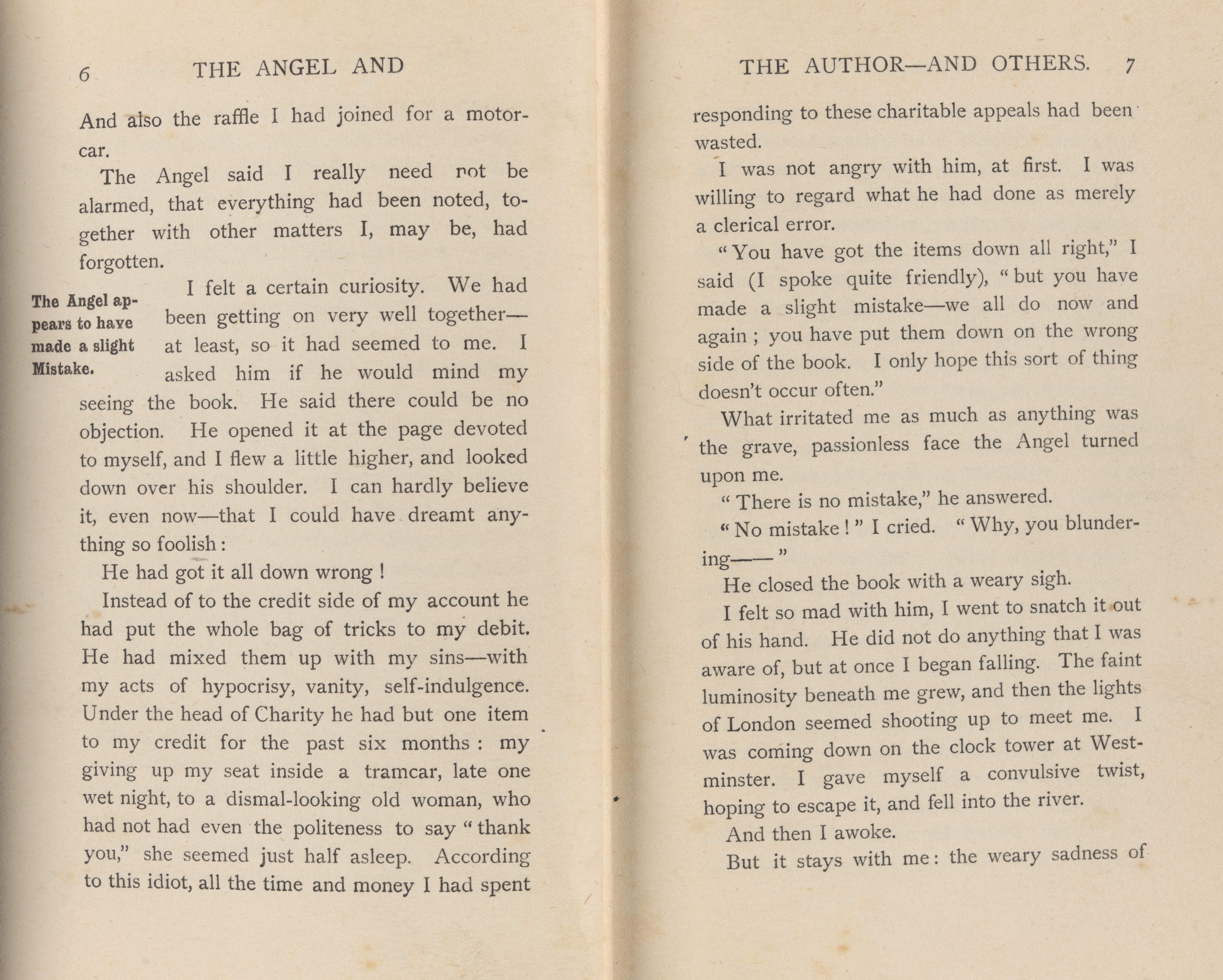

In a 1908 short story entitled “The Angel and the Author” the writer and humorist Jerome K Jerome tells the tale of a wealthy, self-absorbed man who has a dream that he met an angel whose job it is to go around and record everyone’s good deeds so that they can be taken into account when that person arrives at the Pearly Gates and are assessed for entry into Heaven. The Author is at first delighted, assuming that he will be assessed favourably, but the reader quickly gets the idea that many of his so-called “charitable” acts are more for his own benefit than anyone else’s and that the Angel is counting many of them in the negative rather than positive column.

A first edition copy of Jerome K Jerome’s The Angel and the Author (1908) was on display in the Templeman Gallery as part of the exhibition open at this page:

Jerome K Jerome – The Angel and the Author, and others. London: Hurst and Blackett Limited (1908): The Angel and the Author – and others, was a series of twenty essays by Jerome K Jerome in 1908. Jerome Klapka Jerome was born in Walsall on 2nd May 1859. He was an English writer and humourist, and was best known for his comic book ‘Three Men in a Boat’, published in 1889. The first essay in the volume, titled The Angel and the Author, satirises those whose giving is not entirely selfless. The story describes a man who dreams he has died, shortly after Christmas, and goes up to meet the “Recording Angel”. He recounts many of his good deeds such as: “I have been to four charity dinners,” I reminded him; “I forget what the particular charity was about. I know I suffered the next morning. Champagne never does agree with me.” The man asks the Angel if all these deeds are noted in his book. The Angel confirms that they are indeed recorded. The man then sees that the Angel has written them in the wrong column – mixing them up with his sins. The Angel wearily assures him that there is no mistake. The man wakes and wonders what he could have done differently. “Would I have done better, had I taken the money I had spent upon these fooleries, gone down with it among the poor myself, asking nothing in return.” Classmark: PR4825.J3 JER SCR.

[caption written by Beth Astridge, University Archivist, University of Kent]

Although we can laugh at examples mocking the vainglorious efforts of big donors to use their gifts to gain social status, there may also be a slight edge of discomfort for many of us if we suspect that we have been guilty of the same failings in our own way. Whilst most of us will not have the option of getting a museum or hospital wing named after us, in a smaller way do we still sometimes use our giving and generosity to burnish our own self-image and the image we present to others? And whilst this has always been the case to some extent, has the advent of social media – with its pressures to present an unrealistic, idealised version of ourselves to the world – amplified the temptation for all of us to use charity in this way?

Disagreeable Do-gooders

Even when philanthropists are motivated by the “right” things, the way in which they go about their business can still rub people up the wrong way. Hence there is a rich seam of satire that pokes fun at various forms of “do-gooder”, whose methods leave those who encounter their generosity feeling less than well-disposed.

W. S. Gilbert (Of Gilbert and Sullivan fame) captured this beautifully in a verse from his Songs of a Savoyard entitled “The Disagreeable Man”, which paints a vivid picture of a priggish do-gooder whose motives are not in question but whose approach alienates all around him:

“If you give me your attention, I will tell you what I am:

I’m a genuine philanthropist – all other kinds are sham.

Each little fault of temper and each social defect

In my erring fellow creatures, I endeavour to correct.”

Charles Dickens often took aim at busybody do-gooders. Mrs Pardiggle in Bleak House is depicted as a philanthropist, but one who takes a particularly patronising approach in her interactions with the poor. She represents an archetype of the fashion for “home visitation”, which Dickens’s audience would have been very familiar with, which involved women from the middle classes going into the houses of poor families and subjecting them to a mixture of charitable support and moralistic browbeating.

In an 1851 essay entitled “Whole Hogs”, Dickens also poked fun at inflexible social reformers and philanthropic campaigners who refuse to compromise in the pursuit of their goals:

“It has been discovered that mankind at large can only be regenerated by a Tee-total society, or by a Peace Society, or by always dining on Vegetables. It is to be particularly remarked that either of these certain means of regeneration is utterly defeated, is so much as a hair’s-breadth of the tip of either ear of that particular Pig be left out of the bargain.”

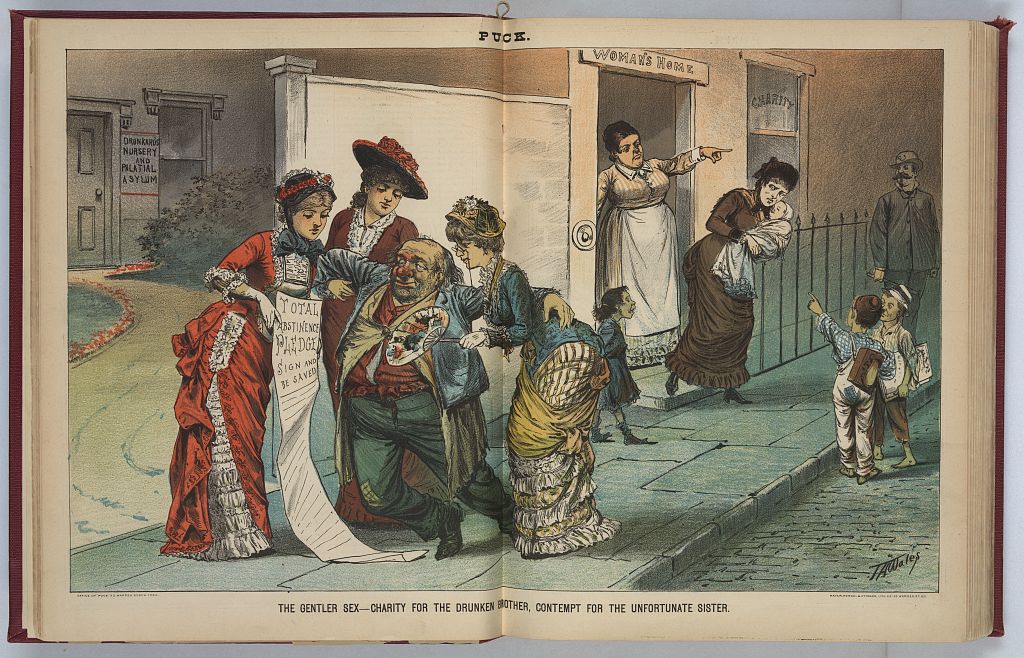

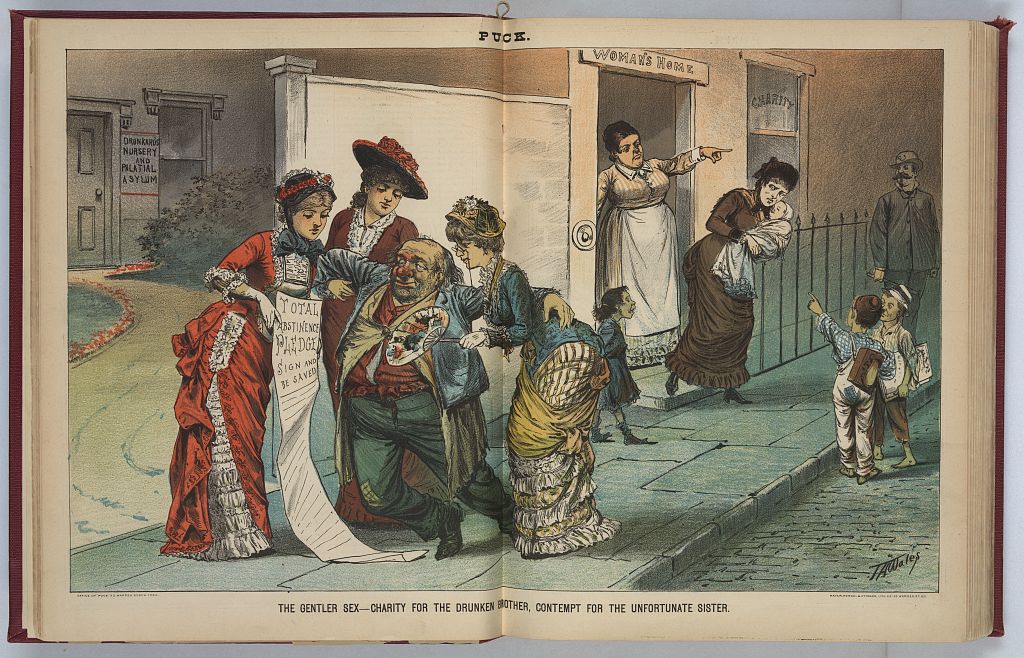

This sort of moral absolutism was also mocked in an 1881 Puck magazine cartoon entitled “The Gentler Sex- Charity for the Drunken Brother, Contempt for the Unfortunate Sister”. It depicts a group of female temperance campaigners holding up a drunken man in the street while they talk to him about their abstinence pledge; meanwhile behind them a young mother holding a baby is being thrown out of a women’s home onto the street.

Wales, James Albert, Artist. The gentler sex – charity for the drunken brother, contempt for the unfortunate sister / J.A. Wales. , 1881. N.Y.: Published by Keppler & Schwarzmann. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2012647287/.

Grand “Philanthropy” at the Expense of Charity

One notable criticism of philanthropy throughout history has been that too often those doing it get caught up in grand schemes and utopian visions, which lead them to lose sight of the consequences of their actions or the need for basic human kindness.

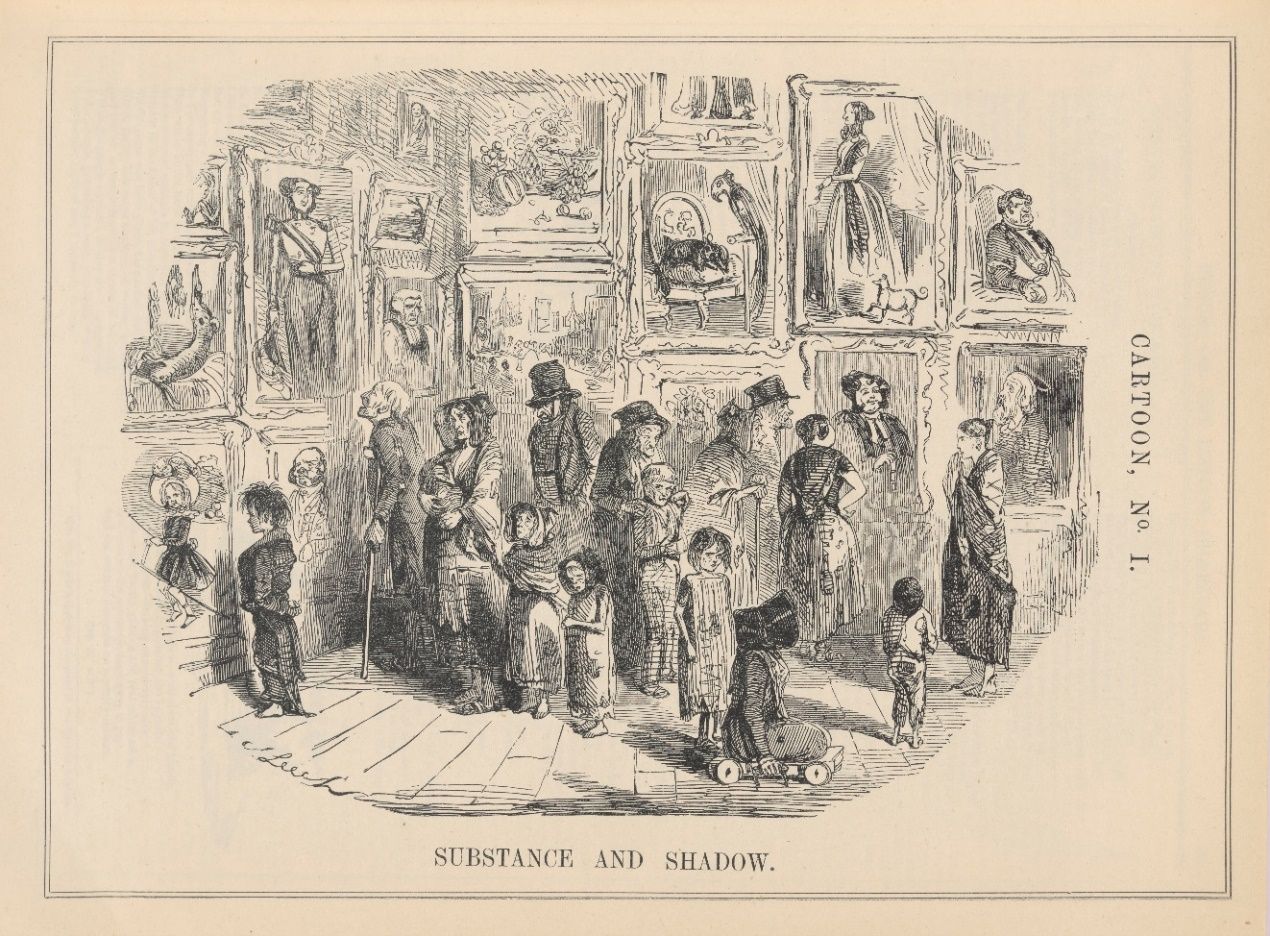

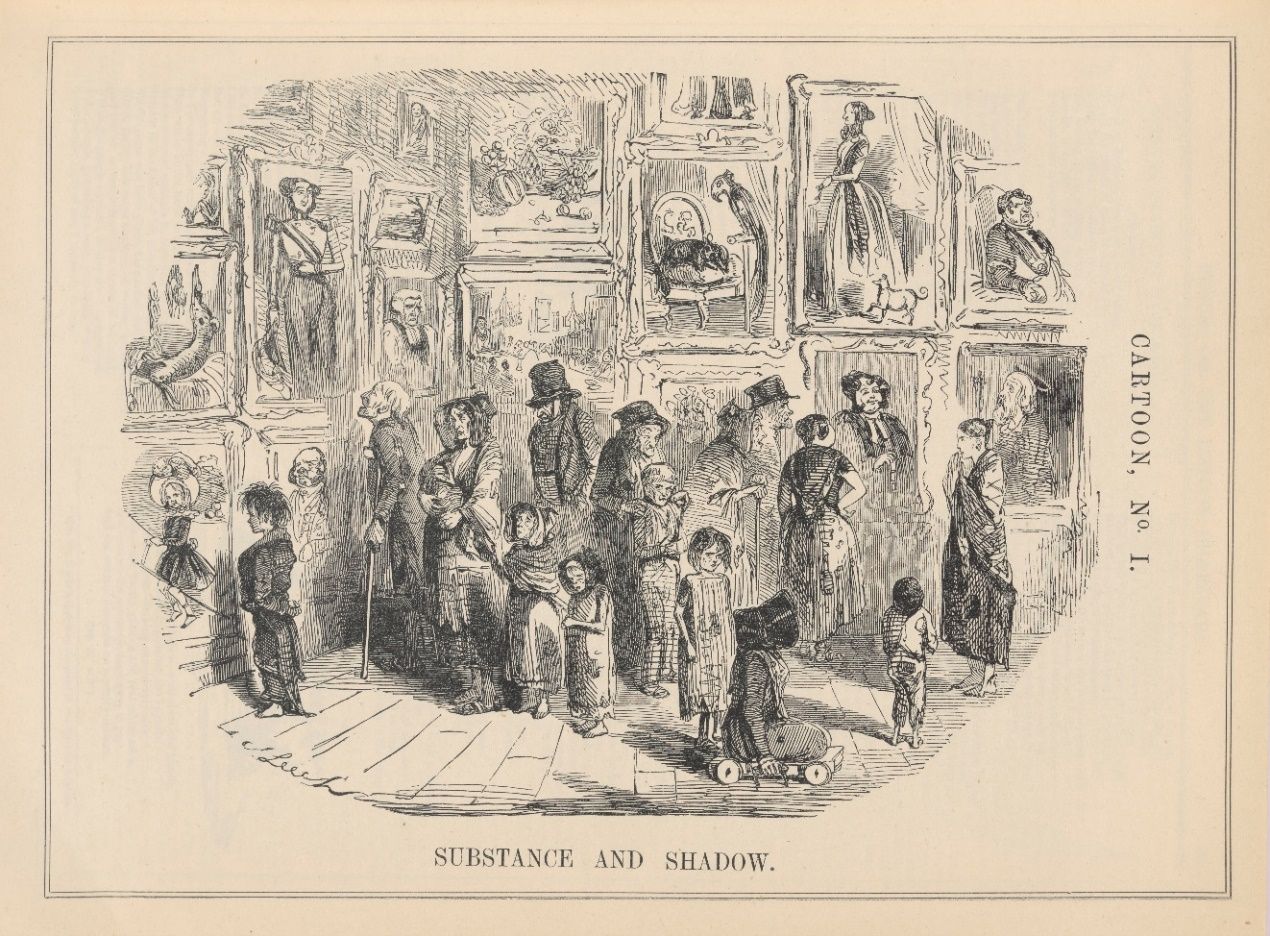

The 1843 Punch magazine illustration “Substance and Shadow” depicts an art gallery in which hungry and ragged children are trying to get the attention of well-dressed adults, who are too engrossed in looking at the exhibition to notice them. The scene is meant to depict a national exhibition which the Government of the day organised, and which drew Punch’s ire on the grounds that such expenditure was grotesque when levels of child poverty were so stark. An accompanying satirical editorial witheringly pretended to commend the government’s decision:

“We conceive that Ministers have adopted the very best means to silence this unwarrantable outcry. They have considerately determined that as they cannot afford to give hungry nakedness the substance which it covets, at least it shall have the shadow… The poor ask for bread, and the philanthropy of the State accords – an exhibition.”

An 1843 edition of “Punch; or The London Charivari” magazine – showing Cartoon No 1: Substance and Shadow – was on display for the Exhibition in the Templeman Gallery:

Substance and Shadow – Punch Magazine, 1843: Punch; or, The London Charivari, was a British satirical magazine published between 1841-1992. Founded by Henry Mayhew and Ebenezer Landells, in 1843 it established the term ‘cartoon’ as we now know it – referring to a humorous illustration or pictorial satire. The cartoon, by John Leech, titled “Cartoon – No 1 – Substance and Shadow” depicts the picture gallery in Westminster Hall and shows poor and ragged children and adults visiting the gallery. The people do not look like they are enjoying the experience of looking upon pictures of ‘high society’ with lives and experiences so different from their own. Leech is satirising the insensitivity of government spending on an exhibition when poverty was such a huge problem. “The poor ask for bread, and the philanthropy of the State accords – an exhibition”. (Caption by Beth Astridge, University Archivist, University of Kent)

In his 1848 cartoon “The Universal Philanthropist”, the famed cartoonist George Cruikshank took more direct aim at individual philanthropists who let their grand schemes for social reform get in the way of more basic human charity. The cartoon shows a well dressed gentleman aiming a kick at a poor family who cower to get out of his way. The father of the poor family is saying “Please Sir, bestow your charity for we are starving!”, to which the philanthropist angrily responds “Interrupting me…at a moment when I am perfecting a grand benevolent plan f Universal Brotherhood and Community of Goods, for the amelioration of the whole Human Race! Why you ungrateful wretch, get out of my house and learn to love your benefactors!”

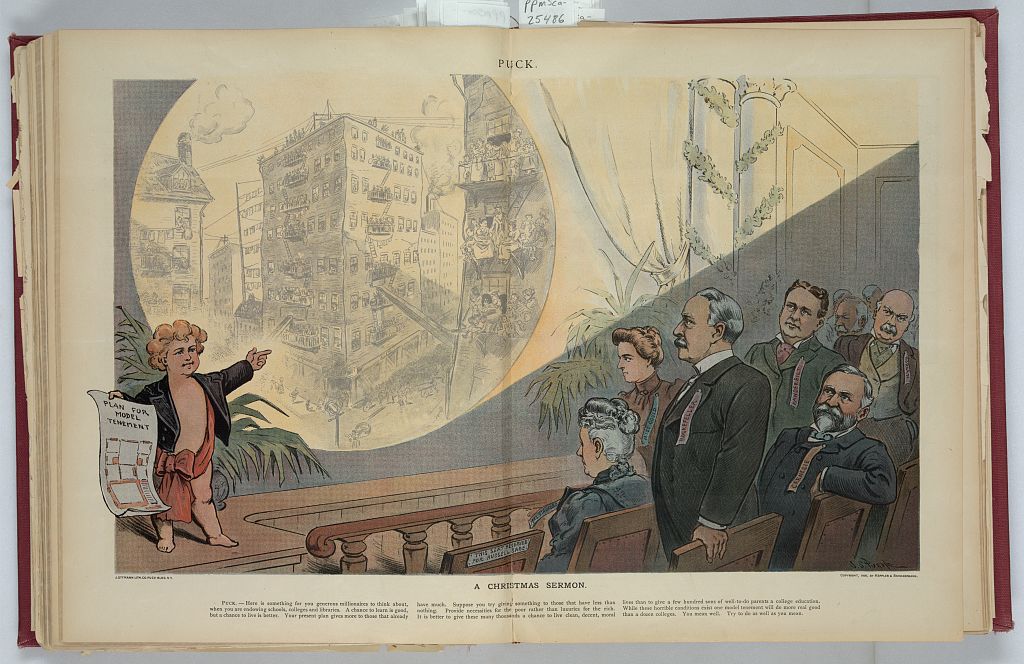

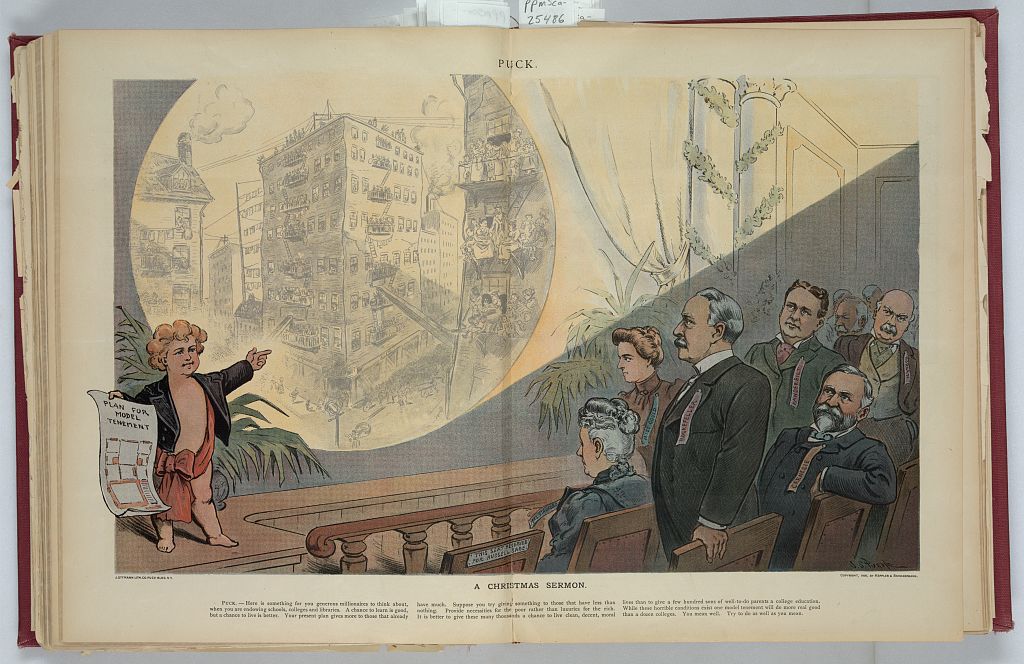

The idea that grandiose philanthropy can sometimes be contrasted unfavourably with the need for more immediate human charity has often been particularly keenly-felt at Christmas. In the 1900 Puck magazine cartoon “A Christmas Sermon”, the character of Puck stands on a stage in front of a crowd of many of the wealthiest and best-known donors of the day (including Andrew Carnegie, J. D. Rockefeller, J. P. Morgan and Cornelius Vanderbilt), holding a plan for a “model tenement” and pointing the audience’s attention towards a picture showing the current state of slum housing. Puck exhorts his audience:

“Here is something for you generous millionaires to think about, when you are endowing schools, colleges and libraries. A chance to learn is good, but a chance to live is better. Your present plan gives more to those that already have much.

Suppose you try giving something to those that have less than nothing. Provide necessities for the poor rather than luxuries for the rich. It is better to give these many thousands a chance to live clean, decent, moral lives than to give a few hundred sons of well-to-do parents a college education. While these horrible conditions exist one model tenement will do more real good than a dozen colleges.

You mean well. Try to do as well as you mean.”

Pughe, J. S. , Artist. A Christmas sermon / J.S. Pughe. , 1900. N.Y.: J. Ottmann Lith. Co., Puck Bldg. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2010651359/.

Philanthropic Hypocrisy

Hypocrisy always attracts satire. In the case of philanthropy, this has most often been seen in critiques that the ways in which donors have made their money are at odds with their efforts to do good through philanthropy. This ties into a wider critique of “tainted donations” i.e. the idea that some money is so ethically problematic or “bad” that it is impossible to do good through giving it away.

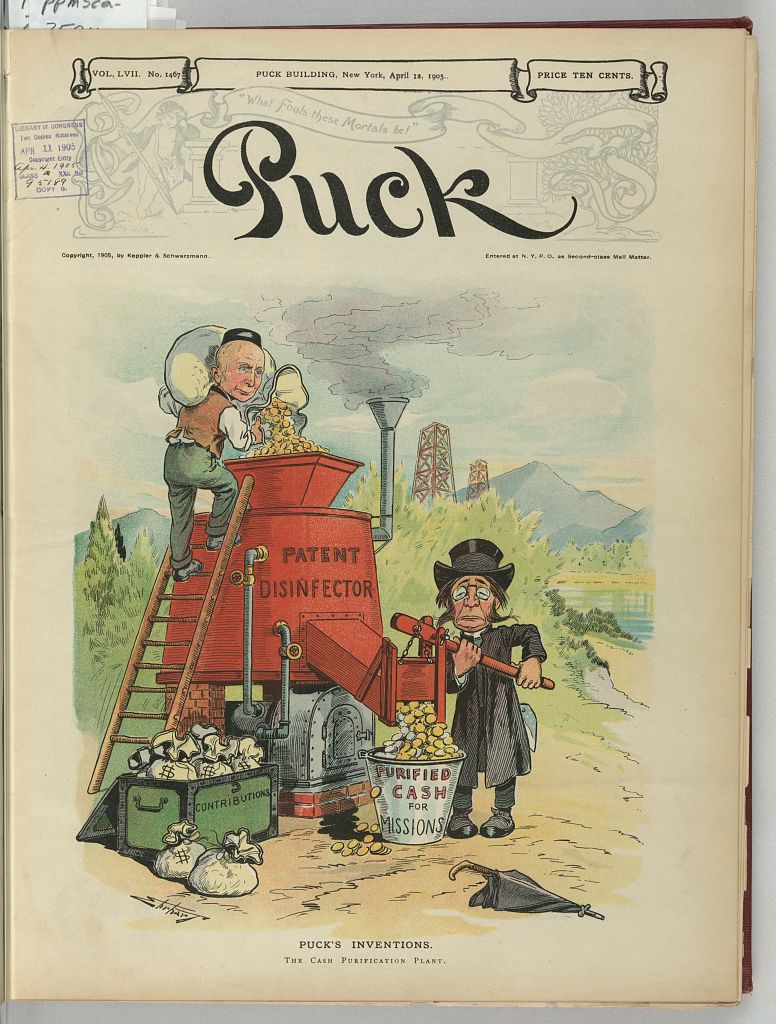

The heyday of satirising tainted donations was in the early 20th century US “gilded age”, when the debate became a mainstream political and social issue thanks to a controversy in 1905 over whether the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions should accept a large donation from J. D. Rockefeller. Mark Twain, for instance, wrote a letter to Harper’s Weekly in the guise of Satan (entitled “A Humane Word From Satan”) which began:

“Dear Sir and Kinsman – Let us have done with this frivolous talk. The American Board accepts contributions from me every year: then why shouldn’t it from Mr. Rockefeller…?”

G.K. Chesterton, meanwhile, penned an article entitled “Gifts of the Millionaire” in which he poured eloquent scorn on Rockefeller’s philanthropy, arguing that it was nothing more than the latest in a long line of attempts to buy absolution through giving. Chesterton famously opened the article by declaring that:

“Philanthropy, as far as I can see, is rapidly becoming the recognisable mark of a wicked man”.

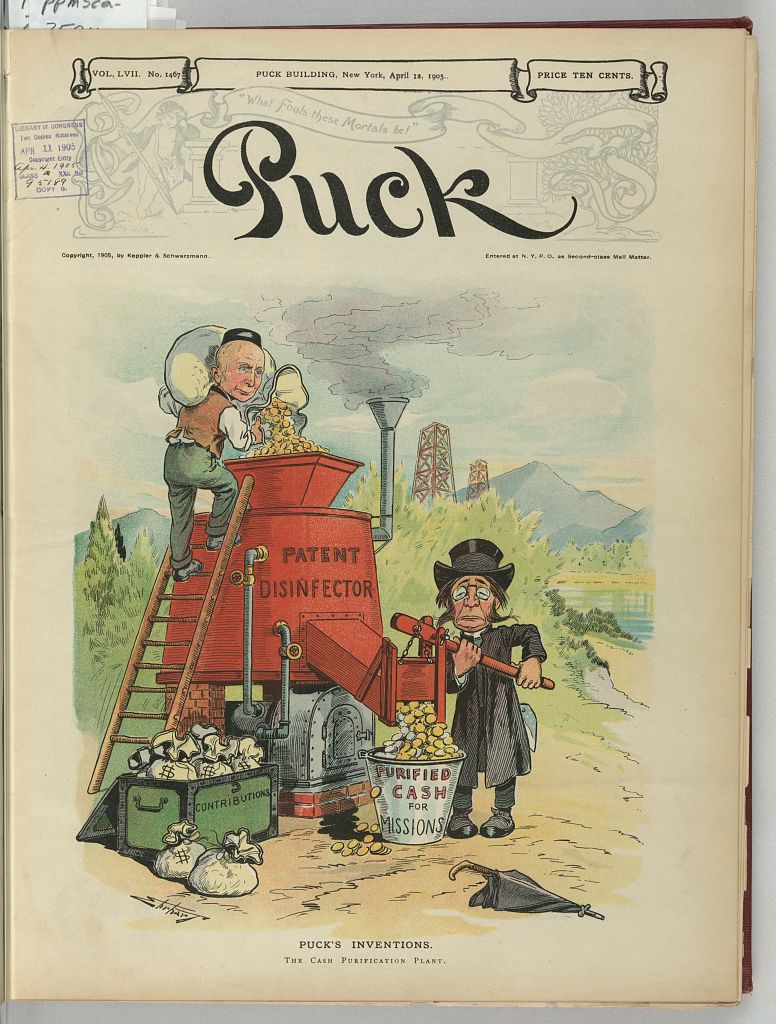

Many cartoonists have also taken aim at tainted donations. A 1905 cartoon called “Puck’s inventions” picked up on the aforementioned scandal over the tainted donations of J. D. Rockefeller, depicting Rockefeller himself on a ladder, feeding coins into a giant machine labelled “Patent Disinfector” which then come out of a chute labelled “Purified Cash For Missions”.

Ehrhart, S. D. , Approximately , Artist. Puck’s inventions / Ehrhart. , 1905. N.Y.: J. Ottmann Lith. Co., Puck Bldg. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2011645691/.

Another Puck cartoon from 1911 entitled “A phase of our tax system – the greater the service, the heavier the tax” depicts two charity workers addressing an oversized man sitting on a throne (presumably a slum landlord), who is taking taking money from a box labeled “Rents” with one hand and putting it into a basket labeled “Organized Charity” with the other, while in the background are run-down tenement buildings.

Concerns about tainted donations continue to be a major source of debate within philanthropy. Scandals such as those surrounding the Sackler family, whose role in the US opioid epidemic has led many to argue that their philanthropy is morally illegitimate, regularly bring the issue back to public attention and raise difficult and long-standing questions about whether it is possible to “do good with bad money” or whether such donations should be refused.

By Rhodri Davies, Pears Fellow, Centre for Philanthropy, University of Kent

[Note: This section of the ‘Exploring Philanthropy’ exhibition highlighted attitudes to the trade in enslaved people and the differences of opinion in Great Britain at the time about the focus of philanthropy within Great Britain and overseas. Some of the archive material displayed in the exhibition and in this blog reflects these contemporary attitudes and language, and depicts Black people in a racist manner. All such items were displayed in the interests of historical accuracy in relating to describing these differing perspectives, as altering them would risk falsifying the historical record. It would also be problematic to source non-offensive modern equivalents with a similar meaning. These items do not reflect the views or opinions of the University of Kent, Special Collections & Archives or our staff.]