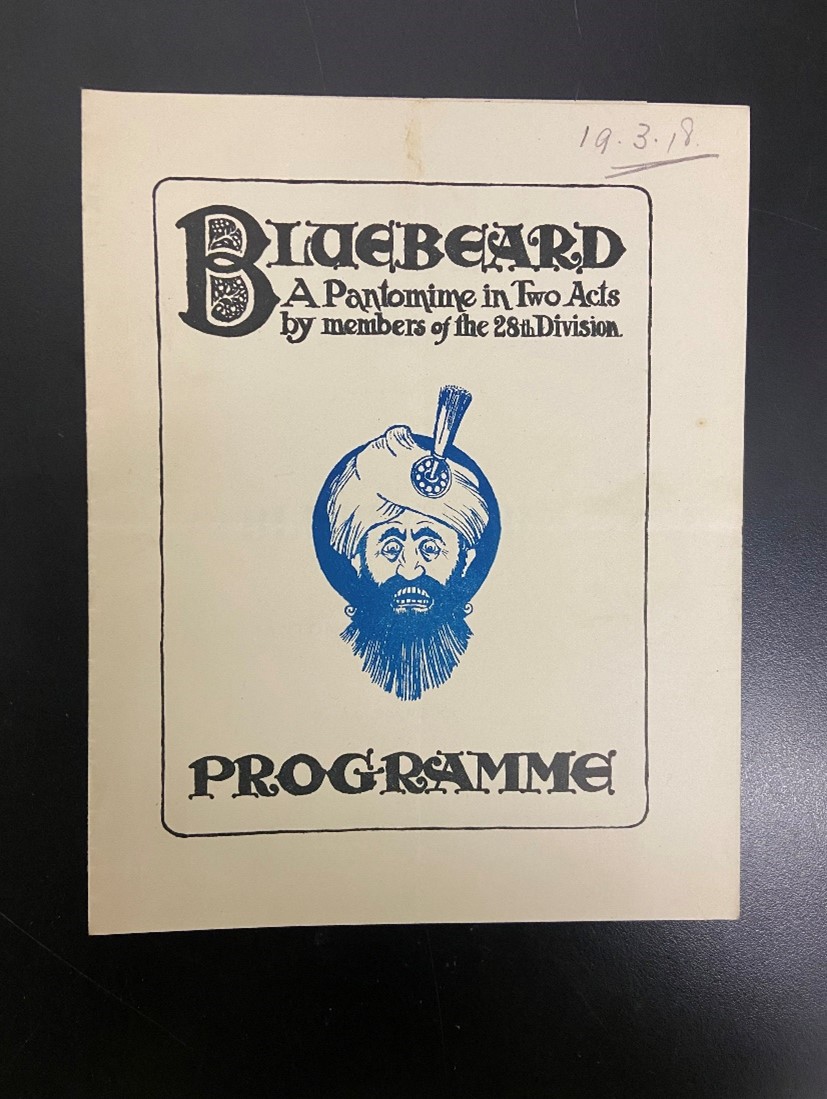

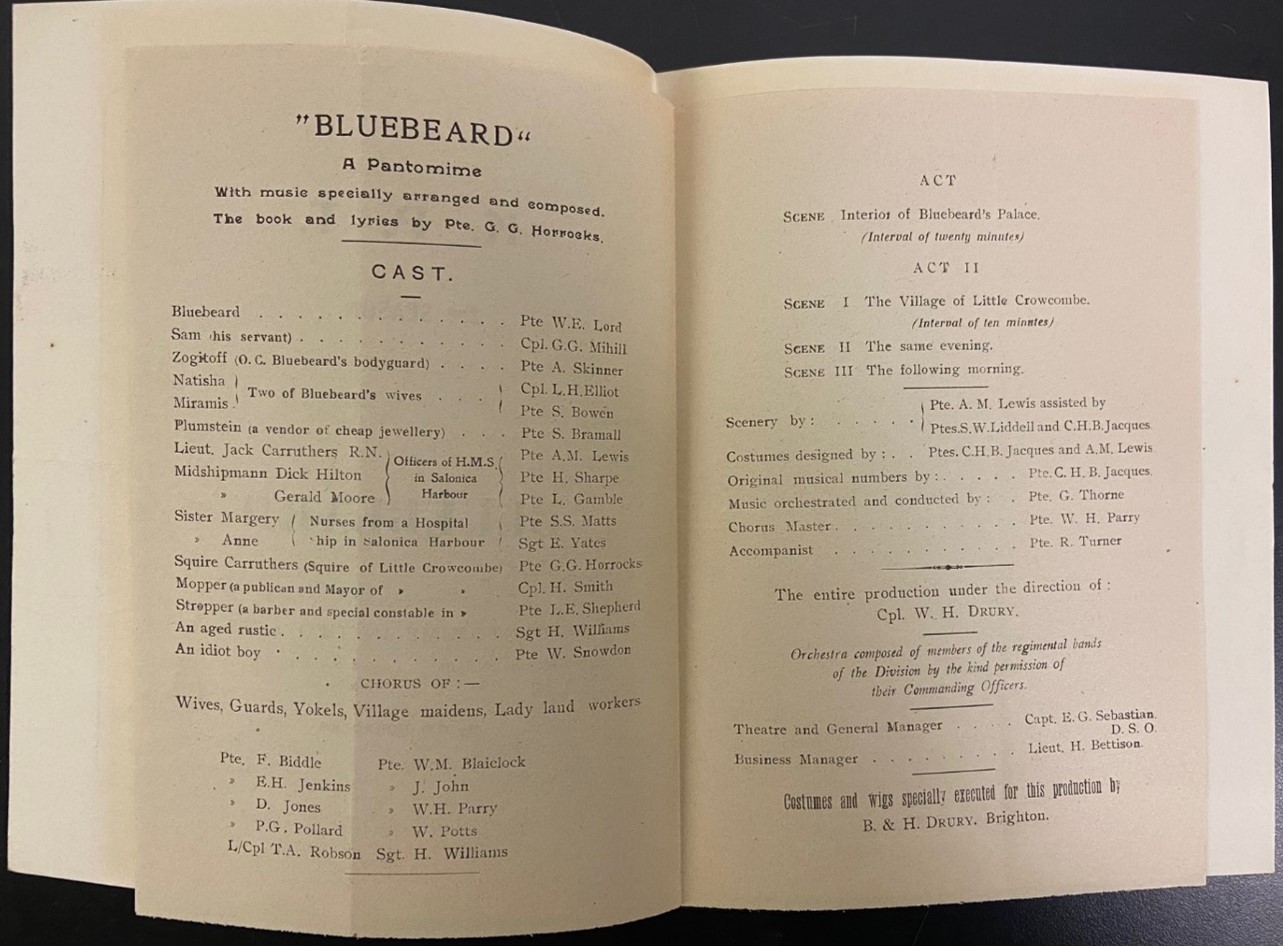

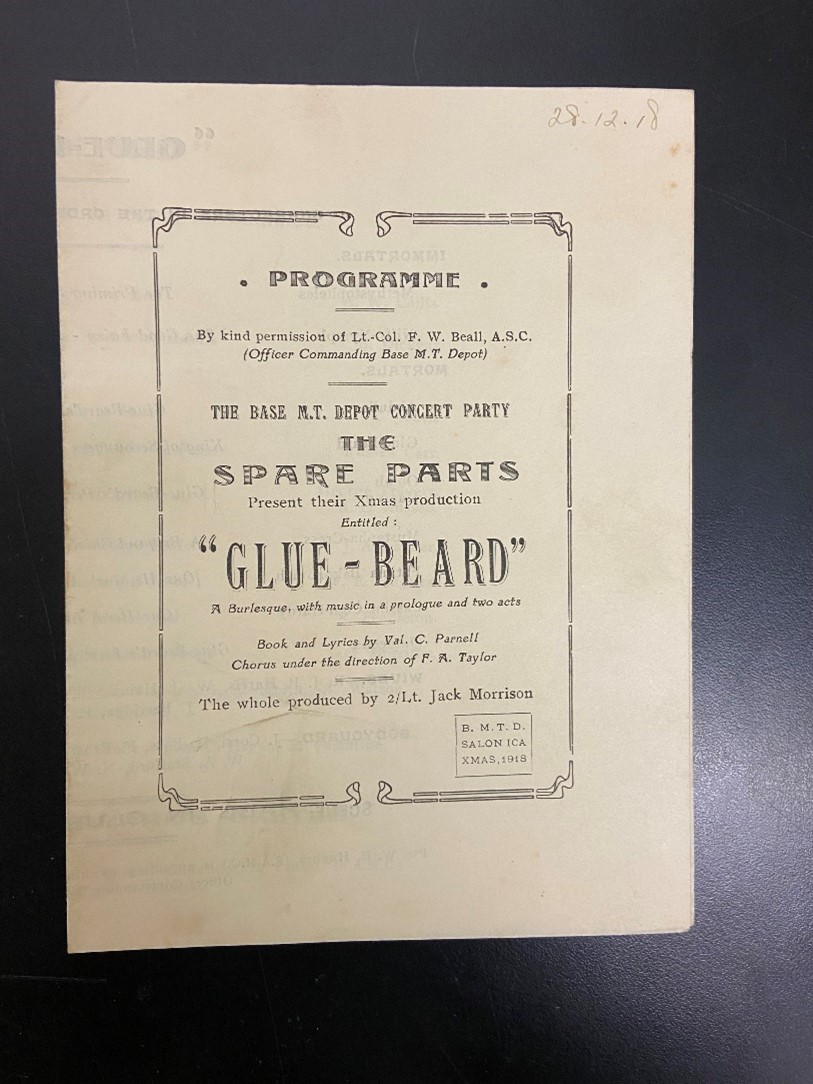

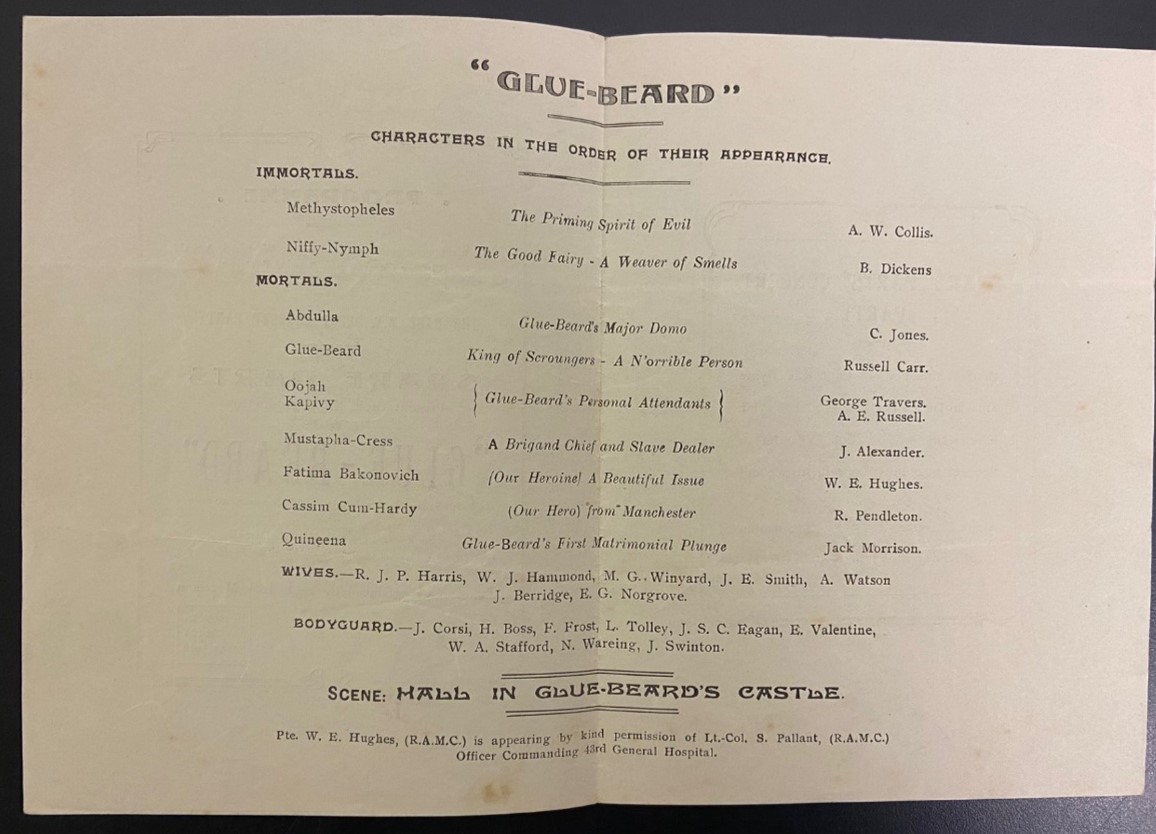

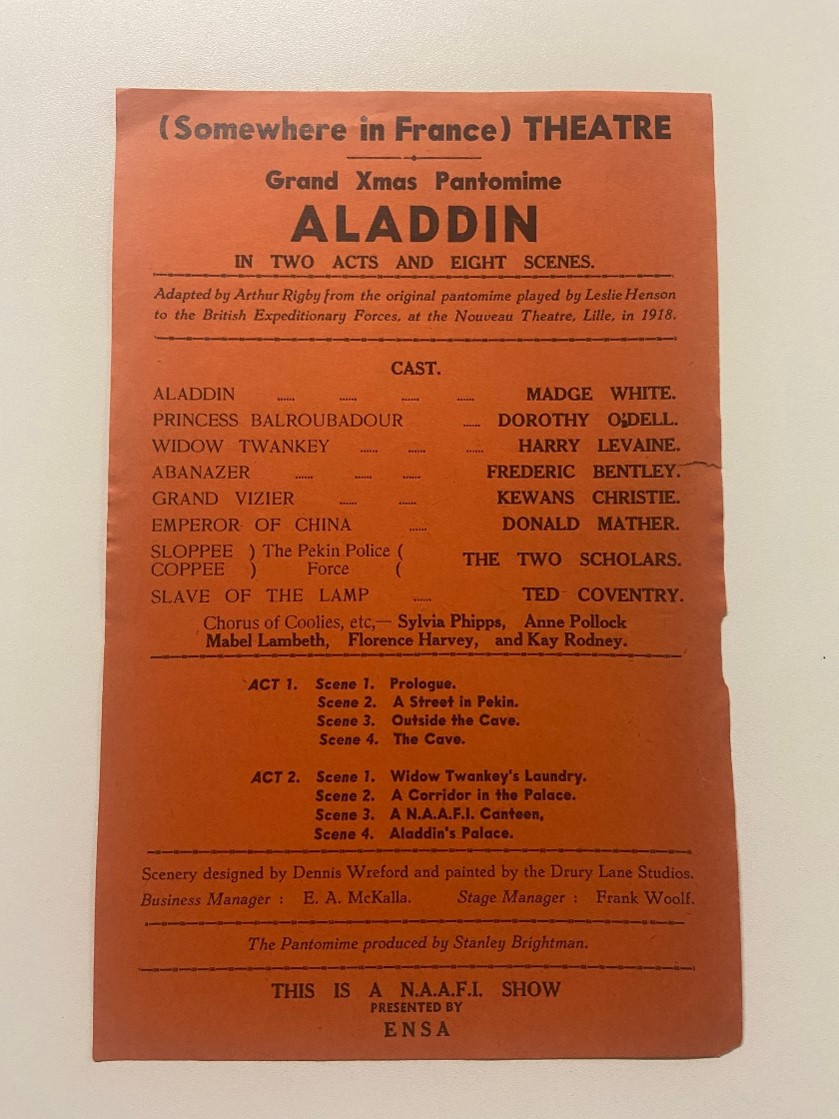

This blog post follows on from the recent post ‘What Did You Do In The War?’ and focuses specifically on the souvenir edition for the performance of Dick Whittington that took place in Salonika during Christmas 1915. In contrast to the First World War programmes for Bluebeard/Gluebeard and the flyer for the pantomime Aladdin, which was performed during the Second World War, which featured in the previous blog post, the souvenir edition of Dick Whittington provides readers with the opportunity to follow the story of the pantomime, examine the dialogues and songs, and see how what troops were experiencing during the First World War became incorporated into the story of the pantomime. In this souvenir edition, Dick Whittington is divided into 3 acts and each section of the blog post focuses on a few examples to demonstrate how the experience of the First World War in Salonika became integrated into this well-known tale.

As well as being a form of humorous and slapstick entertainment, pantomime served as a means of addressing social issues, providing a satirical commentary on serious topics. The pantomime also generally touched upon aspects of everyday life and the experiences of the troops where they were stationed. It is not surprising, then, to see references to the ongoing reality of the First World War within this souvenir edition of Dick Whittington, as well as the context around the First World War more broadly.

Act 1

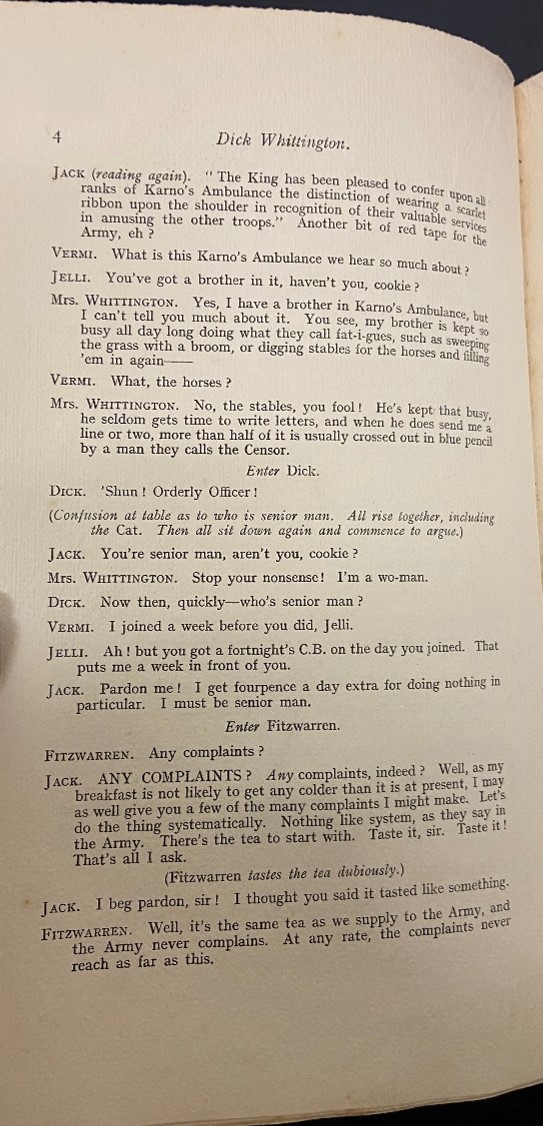

The below section from Act 1 rather comically refers to the efforts of the 85th Field Ambulance to put on this pantomime in the first place, commending themselves on providing entertainment. Rather than overtly refer to themselves, they cast themselves as ‘Karno’s Ambulance’, who the character Jack says have been conferred by the King ‘the distinction of wearing a scarlet ribbon upon the shoulder in recognition of their valuable services in amusing the other troops’.

Extract from Act 1 – Alderman Fitzwarren’s Store in Chelsea from the souvenir edition of Dick Whittington by Frank Kenchington. Performed in Salonika in 1915.

Whilst not overtly stated, calling themselve’s ‘Karno’s Ambulance’ may also be nodding towards the comedian of slapstick and theatre empresario Fred Karno, who was known for his chaos on stage. In fact, disorganised troops of soldiers referred to themselves as ‘Fred Karno’s Army’ during the First World War, perhaps to reflect the chaotic situation in which they found themselves.

The above example also addresses the sorry taste of tea, which Jack complains about to the character Fitzwarren, who tells Jack that it’s the same tea that is sold to the Army. Tea was a staple in the trenches during the First World War and was regularly drank to mask the taste of water, which was transported in petrol tins. Perhaps the tea drank by those in Salonika was not as tasty or as much of a luxury!

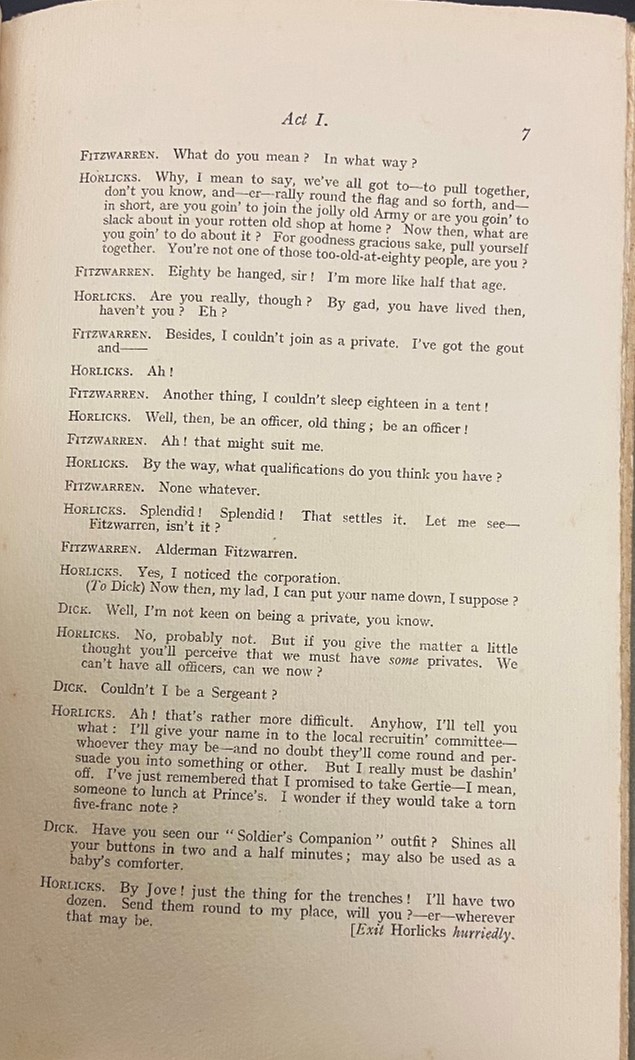

Attitudes around recruitment and joining the Army during the First World War are also present, with the character Horlicks attempting to persuade both Fitzwarren and Dick to sign up and ‘pull together’ and ‘rally round the flag and so forth’.

Extract from Act 1 – Alderman Fitzwarren’s Store in Chelsea from the souvenir edition of Dick Whittington by Frank Kenchington. Performed in Salonika in 1915.

There were many reasons that men joined the army during the First World War and this idea of patriotism and peer pressure resonates in this discussion between these 3 characters. Like recruitment posters of the time (very much thinking about the 1914 Lord Kitchener Wants You poster), this dialogue taps into the sense of fighting for one’s fatherland and emotional ties to the war, particularly about everyone doing their part towards the war effort.

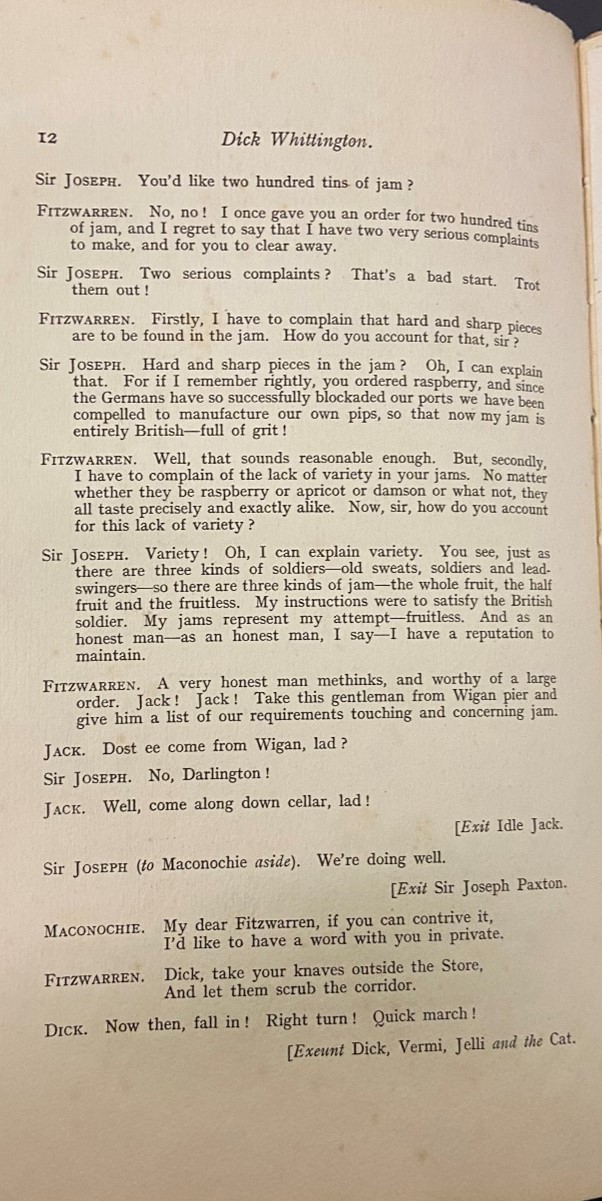

Blockades causing food rations and shortages – both on the Allied and Axis sides – were a tactic frequently employed during the First World War and hunger was used as a deadly weapon. For example, ships going to Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and Turkey, were blockaded by the British and French, causing malnutrition and starvation even after the end of the war. Dick Whittington offers a snippet into this reality from the British perspective in the below dialogue between Fitzwarren and Sir Joseph, blaming the gritty texture of jam, which now has ‘hard and sharp pieces’, and its manufacture within Britain because Germany had successfully blockaded their ports.

Extract from Act 1 – Alderman Fitzwarren’s Store in Chelsea from the souvenir edition of Dick Whittington by Frank Kenchington. Performed in Salonika in 1915.

Act 2

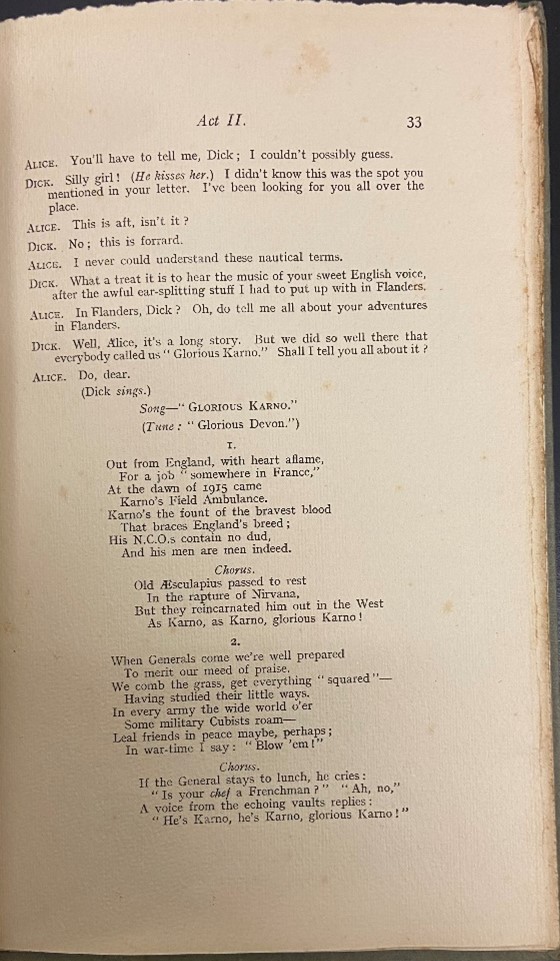

Whilst this performance of Dick Whittington took place in Salonika, other areas where fighting took place during the First World War are also referenced. As seen in the below exchange between Dick and his love interest Alice in Act 2, Dick refers to his time in Flanders and ‘the awful ear-splitting stuff’ that he put up with whilst there.

Extract from Act 2 –On Board The Good Ship “Passover” from the souvenir edition of Dick Whittington by Frank Kenchington. Performed in Salonika in 1915.

Between 1914 and 1918, Flanders suffered heavy bombardment and saw largescale destruction and death, with important cities and villages completely demolished. Notable battles occurred in Flanders, such as the Battle of Passchendaele between July and November 1917, which saw the loss of roughly 275,000 men on the British side and at least 220,000 German soldiers. Dick’s comment may only be a passing reference but still nods towards this devastation.

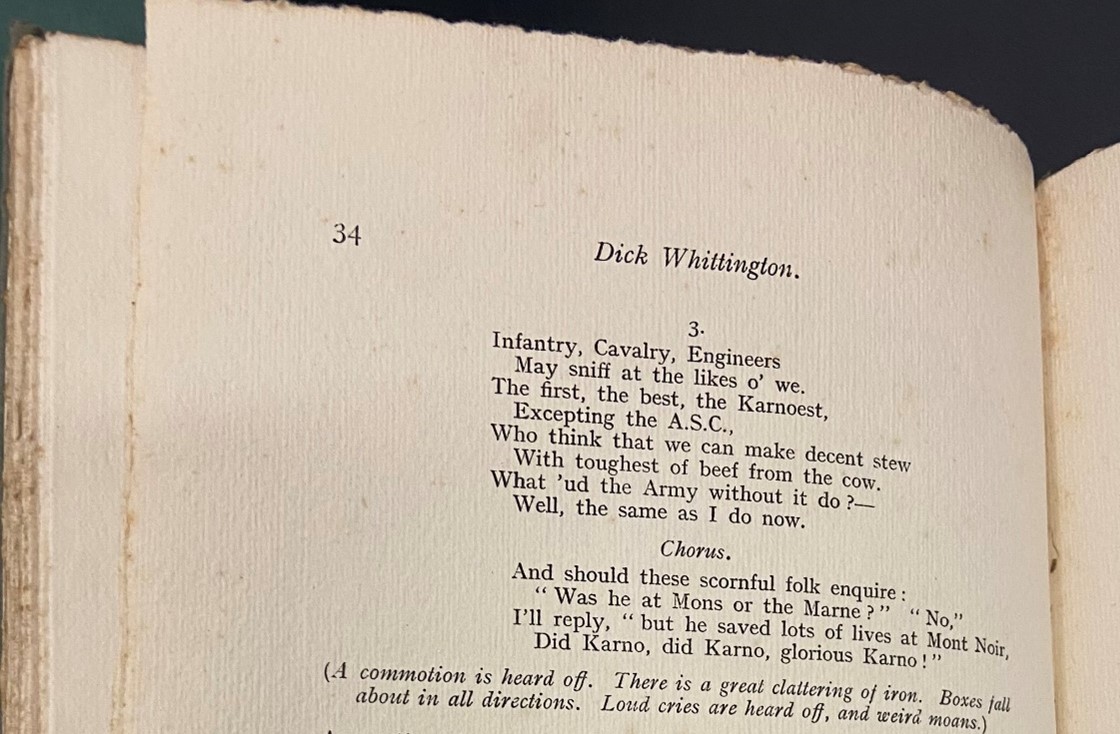

Interestingly the 85th Field Army are again referred to as ‘Karno’s Field Ambulance’, highlighting the contributions that they made ‘Out of England, with heart aflame,/ For a job “somewhere in France”,/At the dawn of 1915’ and their recognition as ‘Glorious Karno’ by ‘everybody’. Even beyond Flanders, in areas such as Mont Noir, the successes of ‘Glorious Karno’ are showcased.

Extract from Act 2 – On Board The Good Ship “Passover” from the souvenir edition of Dick Whittington by Frank Kenchington. Performed in Salonika in 1915.

Act 3

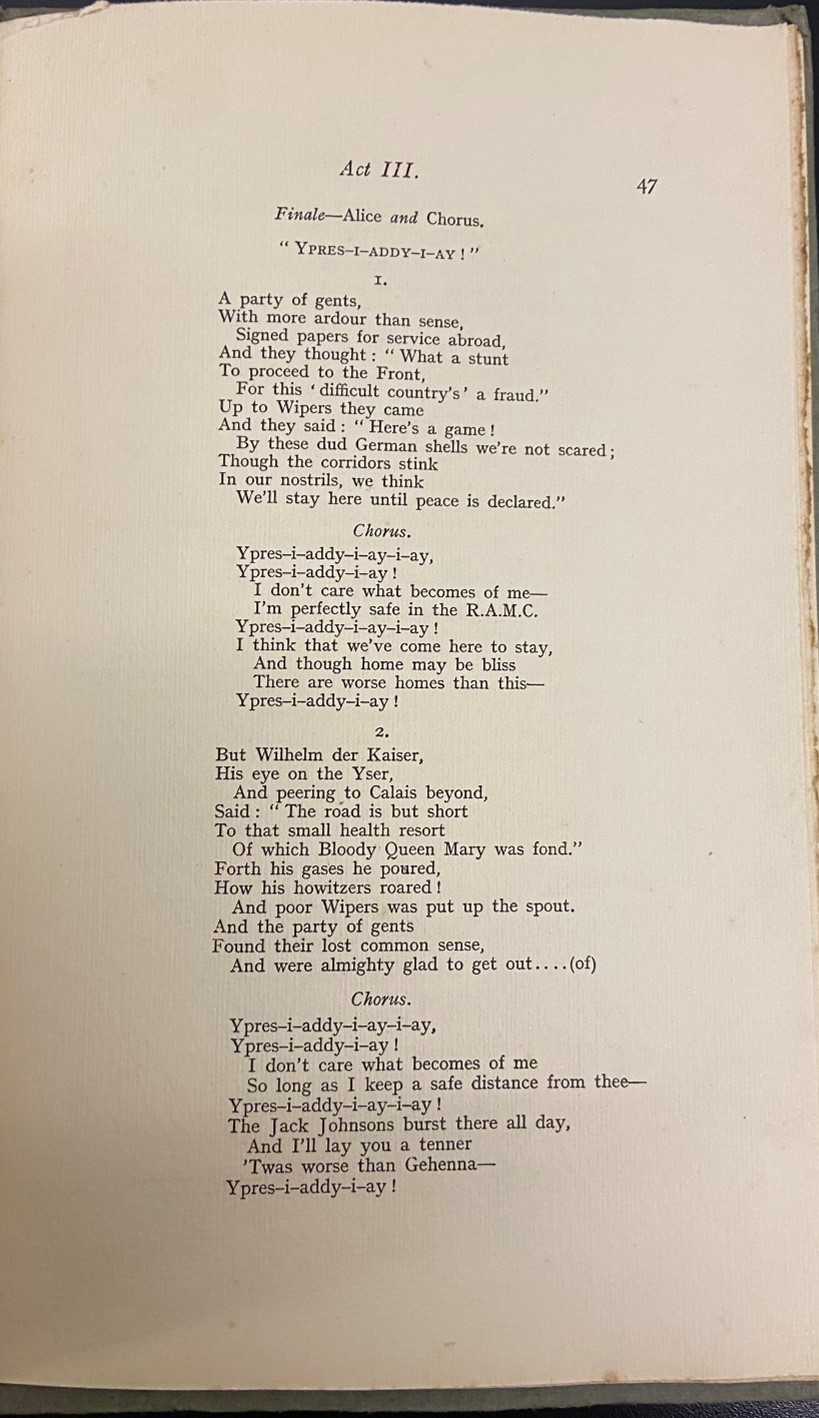

Linked to the discussion about Flanders with the section of this post focusing on Act 2, Ypres is specifically mentioned in the chorus marking the finale of Act 3 and the end of the pantomime.

Extract from Act 3 – Outside Fitzwarren’s Canteen – In The Mists, In The Mountains, “Somewhere In Greece” from the souvenir edition of Dick Whittington by Frank Kenchington. Performed in Salonika in 1915.

The first verse is particularly striking and again reflects societal attitudes about joining the war effort. Reminiscent of Jessie Pope’s poem Who’s For The Game, joining the war was treated as a game by the men, who were not scared of ‘dud German shells’. This of course is far from the futile reality of war but again shows how this pantomime performance made recognisable and provided commentary on general attitudes of the context in which it was created.

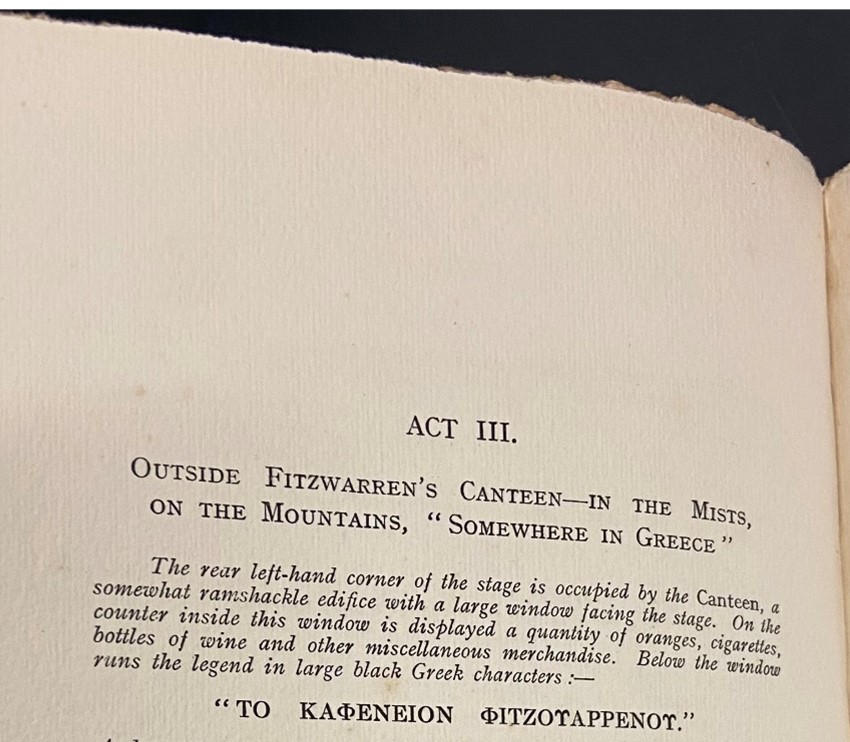

Even the traditional location of Dick Whittington has been influenced by where the 85th Field Ambulance found themselves during the First World War. Not only are various places in which troops fought mentioned throughout the performance, but, rather than maintain the setting of London for performance of Dick Whittington, as would normally be the case, the pantomime has moved to Greece where the troops have found themselves. This location change was made clear from the very opening of Act 3, in which we see that Fitzwarren’s Canteen is located “Somewhere In Greece”.

Opening of Act 3 – Outside Fitzwarren’s Canteen – In the Mists, On The Mountains, “Somewhere In Greece”, from the souvenir edition of Dick Whittington by Frank Kenchington. Performed in Salonika in 1915.

The myth of Dick Whittington stemmed from the streets of medieval London but, in this performance, it is very much the present and the experience of life in Salonika during the First World War that informs the vision, environment, and trajectory of the pantomime.

Conclusion

Themes and issues relating to life at the front and along the Home Front permeate this performance of Dick Whittington. A ‘Ration Song’ was included and there is even a character called Maconochie, no doubt called this because of the tinned food that troops ate, such as Maconochie beef and vegetable stew. Pantomime did not just provide entertainment and a distraction but, also, allowed troops to deviate from traditional stories and devise a setting in which they should share, laugh about, and understand the world in which they found themselves. These are only a few examples from this souvenir edition but there are many more – come visit us at Special Collections & Archives to check it out to learn more about the First World War and remember the experiences and lives of those who fought during the Great War!