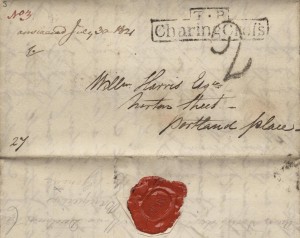

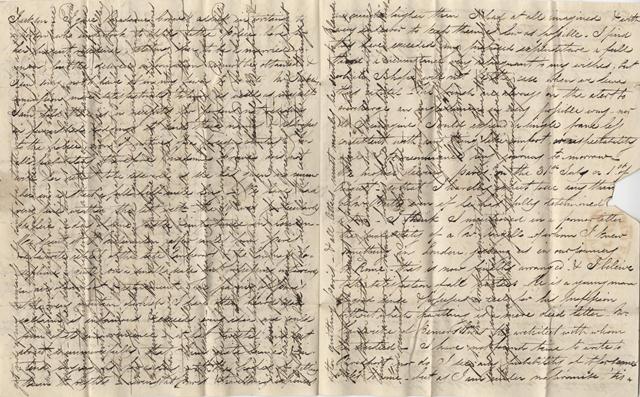

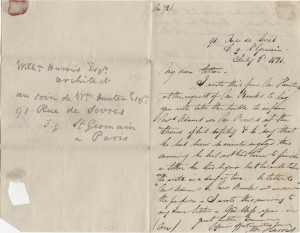

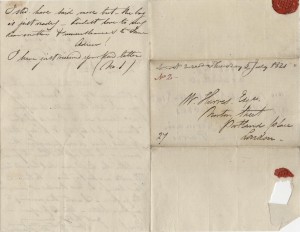

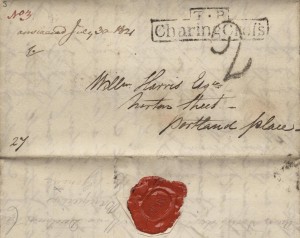

This summer, we’re following young architect William Harris’ trip around Europe, which began in 1821. He left Dover in the company of two friends and travelled to Calais, where he witnessed the celebrations for Corpus Christi. From there, he and Mr Brooks took a leisurely route to Paris. Although William arrived in the city early in July, he only had time to send a quick note to his father to assure him that they were well. We catch up with him on 23 July, when he’d found time in his busy schedule to write a longer letter home.

After the note he sent home on 2 July, William Harris began to feel ‘no little anxiety’ that he had not heard from his father for a full 15 days, nor from his sister for 14 days. The long awaited missive arrived on 15 July, delayed, apparently, by his father’s equally busy schedule! ‘Really, my dear  Father, you must endeavour to spare time to let me hear from you a little more frequently’ William admonished, eager to hear ‘any news from Old England’. Sadly, we don’t have any of William Harris Senr.’s replies to his son in the deed box, but this letter is only the third of twelve, so there’s still a long way for William (and for us) to go!

Father, you must endeavour to spare time to let me hear from you a little more frequently’ William admonished, eager to hear ‘any news from Old England’. Sadly, we don’t have any of William Harris Senr.’s replies to his son in the deed box, but this letter is only the third of twelve, so there’s still a long way for William (and for us) to go!

Once he had settled into his lodgings in Paris, William began his errands in the city which, he said, possessed ‘so many points of attraction’. One interesting ‘commission’ he was sent with was to locate a mysterious ‘Madame Crowe’ on behalf of one Mr Jackson. The information relating to this woman in the letter is sparse, except that she was a married woman and probably ‘not residing in furnished lodgings’. In any case, William reported with some disappointment that he had been unable to locate her, concluding

“In all probability therefore, Madame Crowe does not wish her whereabouts to be discovered as she had given no number in a street a full half a mile long.”

Considering the upheaval in France from the fall and two exiles of Napoleon, with the involvement of the European Coalition to restore the Bourbon monarchy, Paris was perhaps one of the easiest places in Europe to stay hidden at this time.

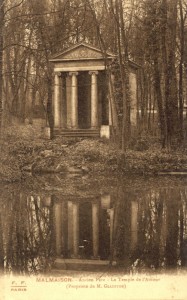

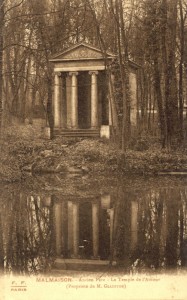

Le Temple de ‘Amour, Malmaison (HJ PC:301)

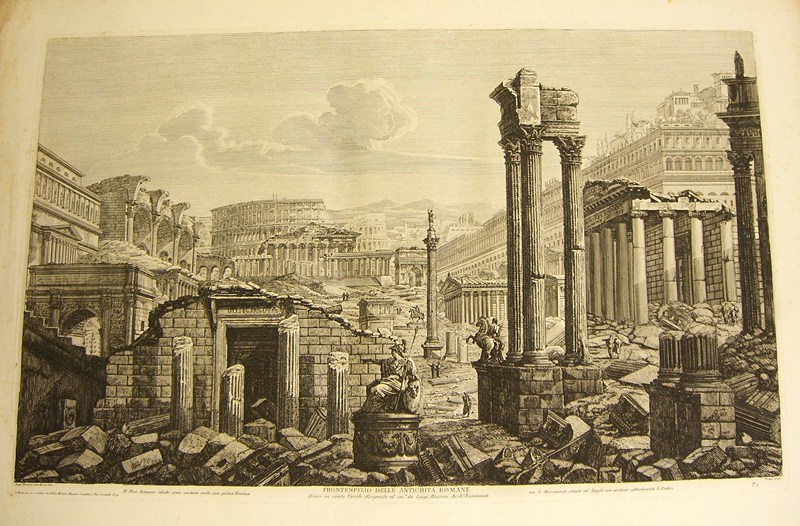

Aside from commissions from friends and acquaintances, William’s main reason for travelling through Europe appears to have been to take in objects of art and architecture, for which the small group visited Malmaison on 19 July. This chateau was ‘a favourite retreat of the late Emperor’s and the Empress Josephine’; Josephine had bought the estate while Napoleon was in Egypt, with the expected proceeds of that campaign. She spent years and a small fortune restoring the chateau and its gardens as well as creating a menagerie which roamed free through the grounds. After her divorce from Napoleon in 1810, Josephine kept the chateau until her death in 1814. William recalled his father often telling him:

“the frowning of Paris on the very mentioned of which [Malmaison] is infamous…”

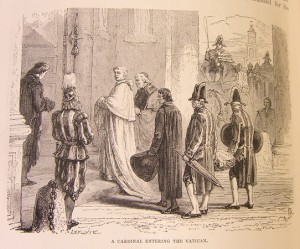

Of course, it wasn’t just France which was going through difficult times politically; there was a good reason why William wanted all of the news from old England. He noted his whereabouts on 19 July 1821 for a good reason: it was the date of King George IV’s coronation, after the death of the mad King George III in 1820. George IV had been Prince Regent during periods of his father’s incapacitating illnesses, although he had largely left the role of governance of the country to his politicians. While the coronation of the new King appeared didn’t appear to threaten any crisis, there was drama on the day due to George IV’s difficult relationship with his wife.

Coronation banquet of George IV by an unknown artist, c.1821

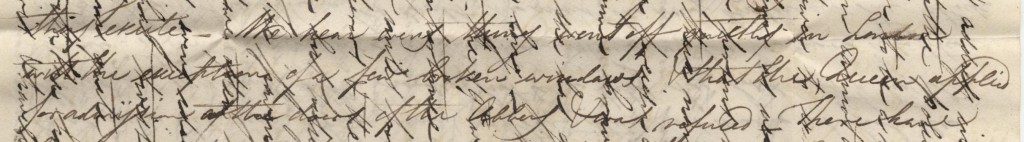

Having been married in 1795, reluctantly, to Princess Caroline of Brunswick, the Prince Regent’s marriage quickly ran into difficulty. After the birth of their only child, Princess Charlotte, the royal couple separated in 1796. Queen Caroline went to live on the continent in 1814, but at her husband’s coronation in 1821 she decided to return to London to assert her rights. William noted:

We hear that everything went off quietly in London with the exception of a few broken windows and that the Queen applied for admission at the doors of the [Westminster] Abbey and was refused”

George refused to recognise Caroline as Queen, and made efforts to ensure that European monarchs did likewise. Although he tried to divorce her and later to annul the marriage, these efforts proved unpopular with the public. In the end, the marriage ended quietly: Caroline became ill on the day of the coronation and died on 7 August, with some rumours that she had been poisoned. William’s brief note of the incidents on coronation day suggest that he, at least, had little interest in the quarrels of the royal family. In any case, his excitement about his trip around Europe was far more important.

News of the coronation reaches William in Paris

William was not the only architect who had left Britain to experience the culture and art of the rest of Europe; as well as his friend Mr. Brooks, with whom he had travelled from Dover, a Mr Angell joined them on their onward journey from Paris to Rome. William wrote:

“He is a young man of good sense and possesses a zeal for his profession without which something is a mere dead letter.”

The band of architects sound more like serious professional scholars than a gap year party, but then it’s likely that William would have wanted to impress the seriousness of his enterprise onto his father who was paying his bills.’Living at Paris and travelling expenses are so much higher than I had at all imagined’ he complained in his letter;

“and with every endeavour to keep [expenses] as low as possible, I find that they have exceeded my proposed expenditure a full third”

Even so, he assured his father that the costs would drop once they left the capital, although ‘the French are always on the alert to overcharge an Englishman’. It was not, he insisted, the pursuit of luxury which had cause this spending;

“nor do I imagine I could spend a single franc less consistent with any thing like comfort or respectability were I to recommence my journey tomorrow’

-

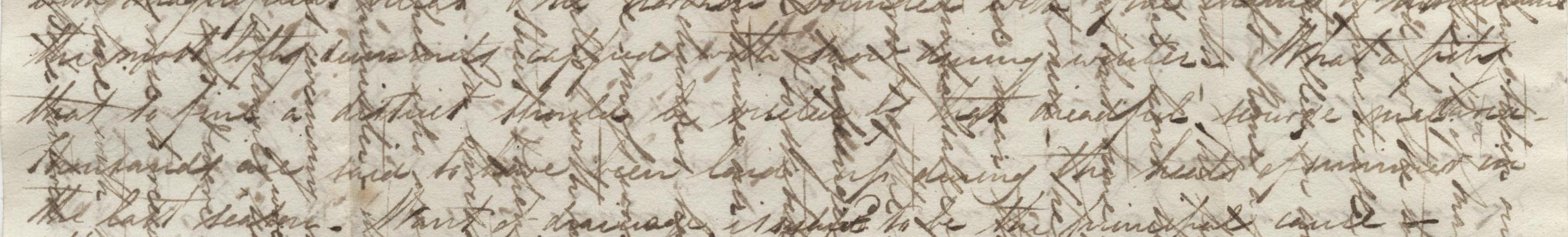

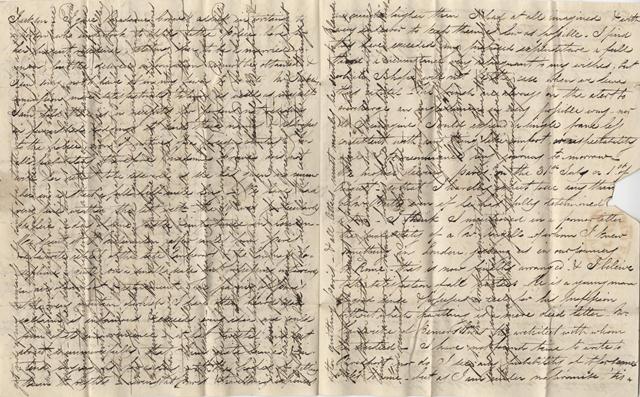

William’s letter from Paris

William evidently thought of his family at home frequently during his time away; his father, mother, sister, Mr Evans and ‘Jane’ are mentioned in every letter. This letter also mentions another member of the family;

“I am sorry to hear poor Dick has been obliged to undergo an operation.”

As I was transcribing the letter, I thought that sounded interesting; who was Dick? Probably not a member of the immediate family, but perhaps a servant or someone close enough to the Harris family that they had ensured he got the operation which he needed? Leaving aside the difficulties of nineteenth century surgery, I thought that this would give an intriguing insight into a gentleman’s relationship with his dependants. In some ways, it does, but not quite as I was expecting. William goes on:

“It would be perhaps be as well to avoid taking him over the stones as much as possible. He is an excellent little horse but tis a pity he has not a lighter vehicle to draw…”

So there you go, the Harris family were very close to their horses! William goes on to advise his father on how to deal with Dick’s lameness, with as much interest as if he was a long-term servant of the family.

“[I’m sorry to hear that] poor Dick has been obliged to undergo an operation”

The small band of architects intended to leave Paris on 31 July and continue their journey via Compiegne, Rheims, Dijon, Lyons, Nismes and then reach Geneva. The itinerary was not fixed;

“at the first mentioned places our stay will be uncertain and will be regulated by the interest they excite.”

And while he was racing around Europe, William was eager to stay in touch with his friends and family at home;

“If yourself or my sister could possibly find time to write to me immediately on the receipt of this by the very next bag…”

“…by the very next bag…”

Sending off his tightly packed, overwritten letter back home, William presumably went off to enjoy his last week in Paris, and to gather some more anecdotes to tell in his next letters. It’s just a lucky coincidence that these letters have survived nearly 200 years so that we can share his excitement today.

William’s letter from Paris and related archival materials will be on display in the Templeman foyer for a limited time only! Pop in to have a look and learn more, including why Lord Byron was causing a stir in Paris in 1821.

The launch was started with a lecture by Professor Kate Newey from the University of Exeter, who spoke about the subtle protest in suffragette parlour dramas and the deliberate inversion of the female stereotype by campaigners for womens emancipation. The event then moved to the gallery space in the Templeman Library, where everyone enjoyed this rare opportunity to see such different collections side by side.

The launch was started with a lecture by Professor Kate Newey from the University of Exeter, who spoke about the subtle protest in suffragette parlour dramas and the deliberate inversion of the female stereotype by campaigners for womens emancipation. The event then moved to the gallery space in the Templeman Library, where everyone enjoyed this rare opportunity to see such different collections side by side. This exhibition really is an intriguing and entertaining look at the way in which perceptions of women and society as a whole were being challenged a century ago and is only on until 31st May, so please do come and have a look around when you’re next in the Templeman.

This exhibition really is an intriguing and entertaining look at the way in which perceptions of women and society as a whole were being challenged a century ago and is only on until 31st May, so please do come and have a look around when you’re next in the Templeman.