Written by Daniel Quirk, student on HI6062: Dynasty, Death and Diplomacy – England, Scotland & France 1503 – 1603

The Templeman Library’s Special Collections & Archives Department holds a rare 1587 edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles; a book that collates the works of some of the most influential pre-seventeenth-century writers of early English, Scottish and Irish history in a single place. Printed in gothic English font, the book’s characteristics imply a lot about its intended use as an object, which will be explored in this blog. This blog will also demonstrate that the book was the product of a growing late sixteenth-century belief that Scotland and England were becoming a shared space and that Holinshed believed it was important for the national histories of both nations to be understood within a single book.

Holinshed’s Chronicles were collated by Raphael Holinshed (1529-1580) with the first edition published in 1577, and this particular book at the Templeman Library published as the second edition in 1587 under the supervision of Holinshed’s successor, Abraham Fleming. Holinshed and his successor brought together works by authors that dominated the contemporary understanding of England’s and Scotland’s respective histories, such as Hector Boece whose ‘Scotorum Historiae’ was translated and used in the ‘Historie of Scotland’ section for Holinshed’s book along with works by other authors on Scotland’s history.

External view of the 1587 Holinshed Chronicles Volume II in the Templeman Library’s Special Collections & Archives

The first obvious feature of the book is that it is very large, measuring 36cm x 23cm x 8cm. The size suggests that this book was not designed to be an easily portable book but was most likely intended for personal educational use as part of someone’s collection. The use of English translations instead of Latin suggests that the intent of the book was primarily educational, bringing about greater awareness of the ancient origins and histories of the British Isles by using a more widely understood language. Furthermore, as paper was an expensive material to use in the sixteenth-century, the impressive size of the book and its pages also implies that the book was materially valuable to its owner as well as an important educational resource. Evidence of intricate gold-leaf patterns on the cover reinforces this argument that this book was produced with expense to impress.

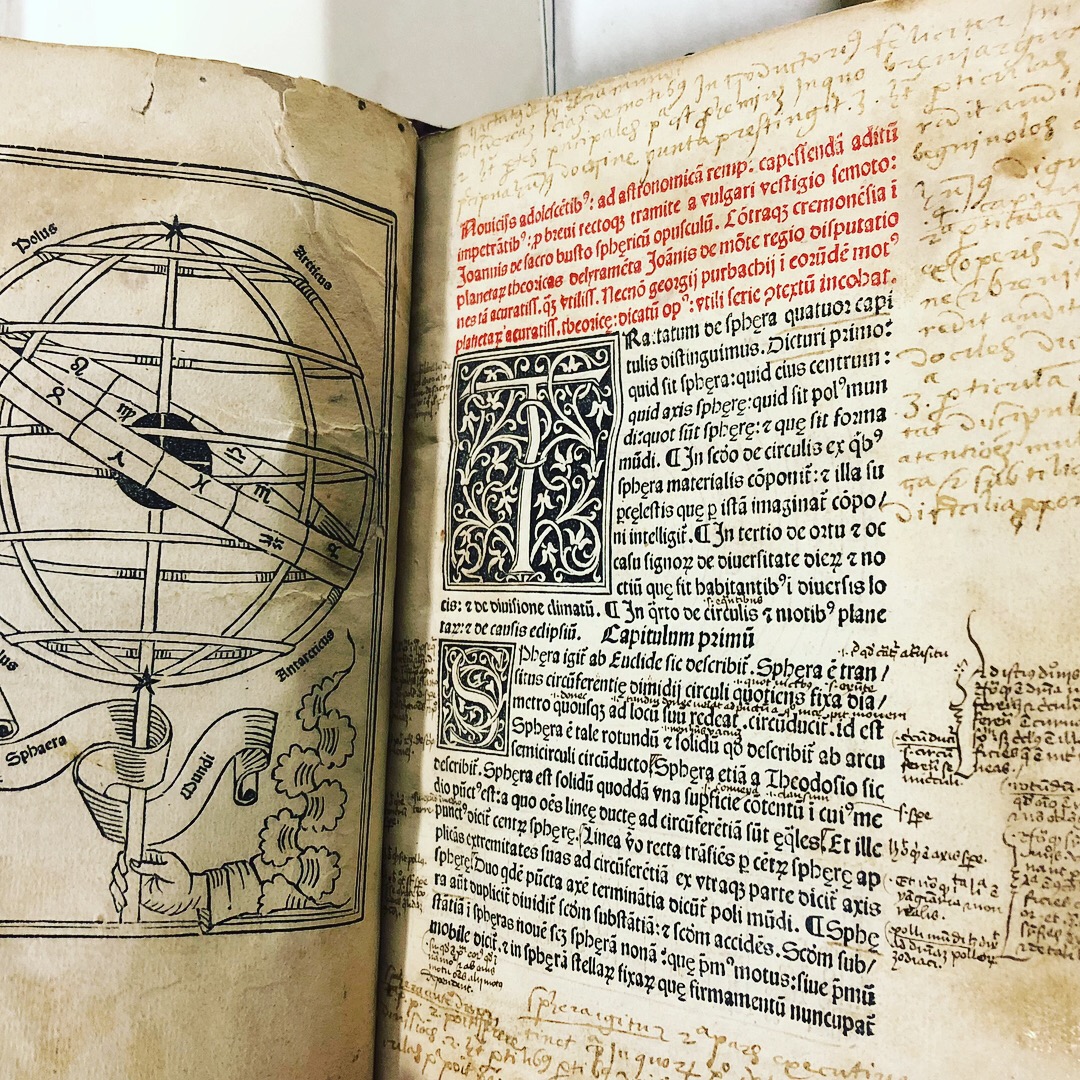

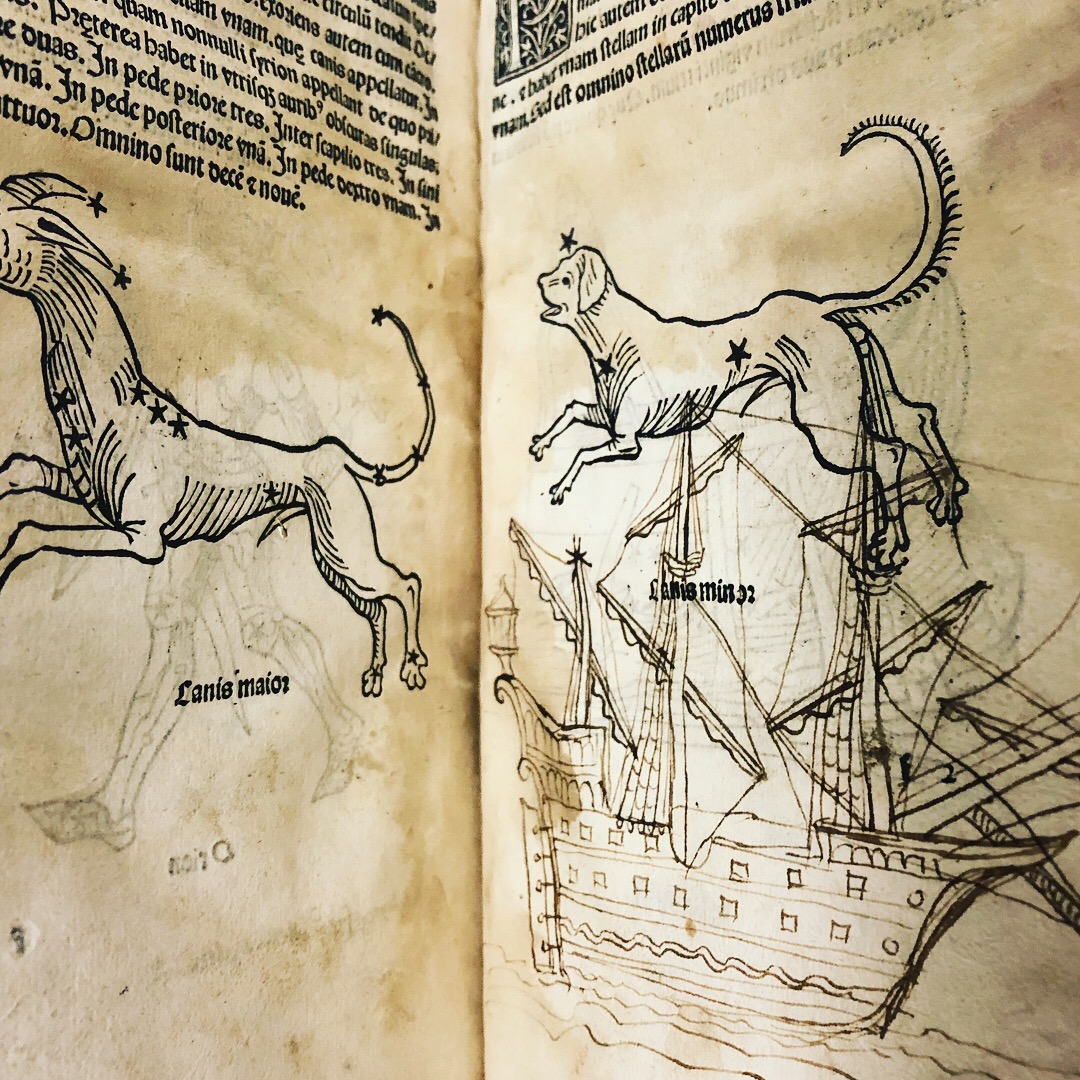

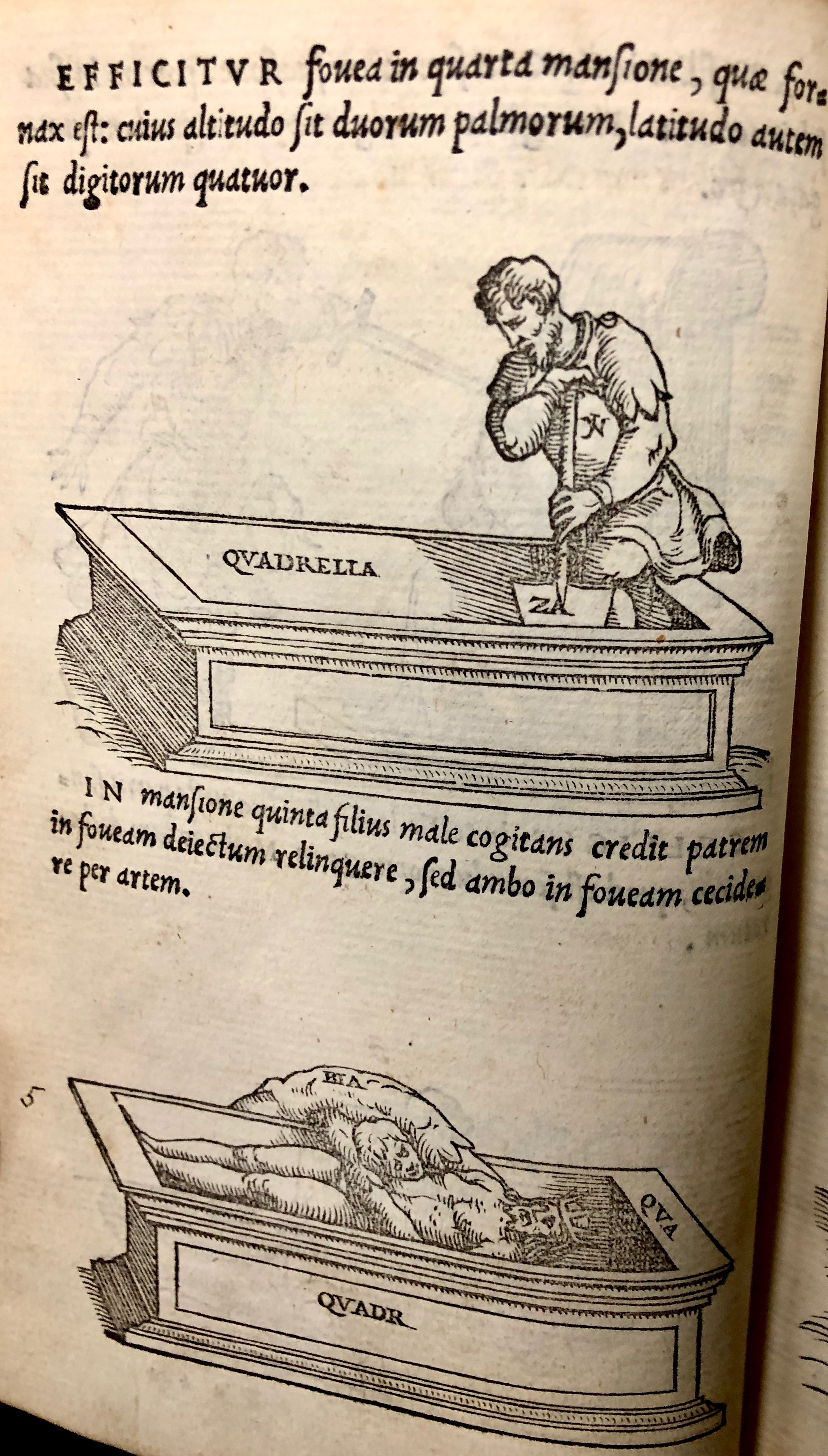

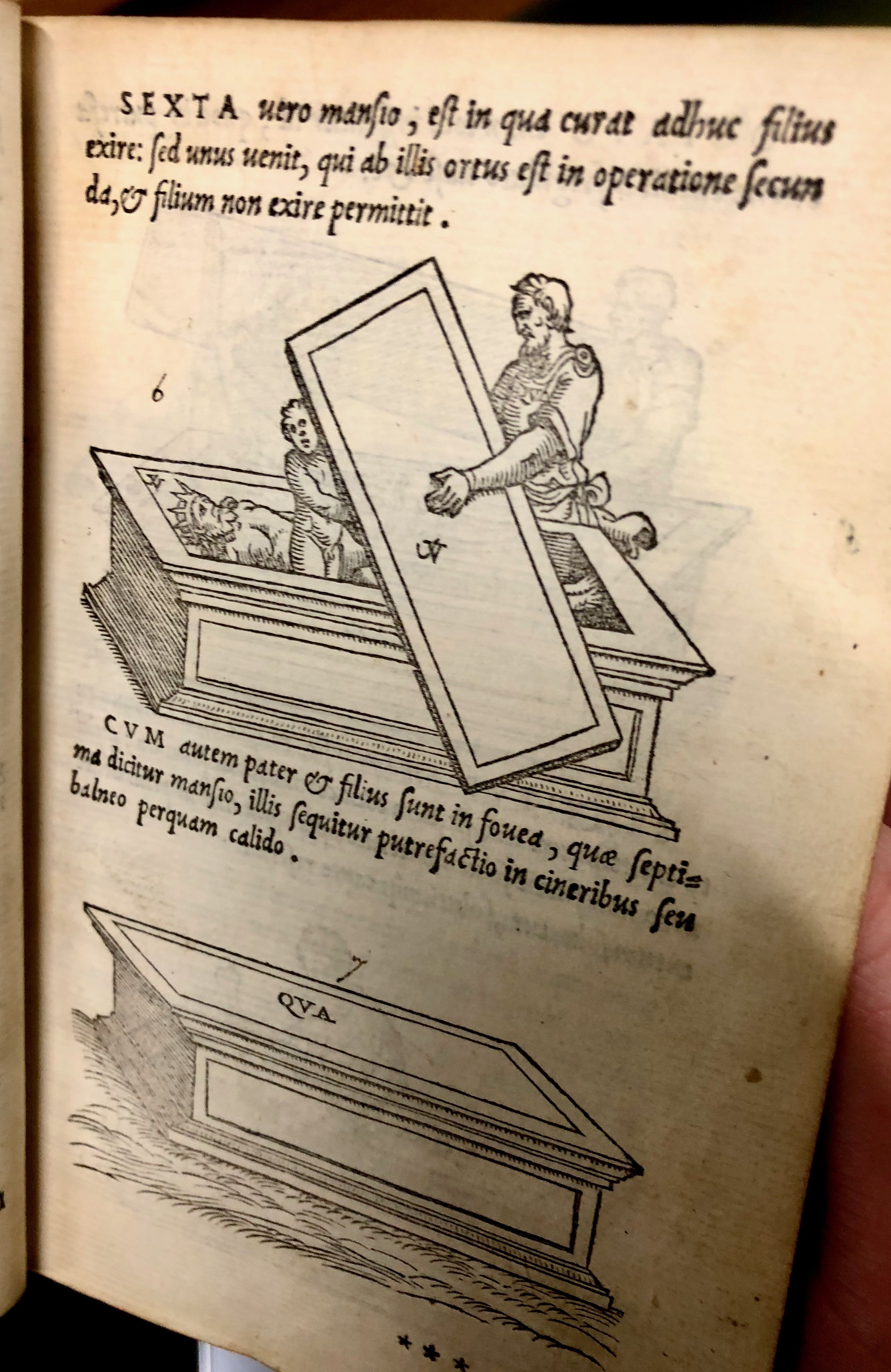

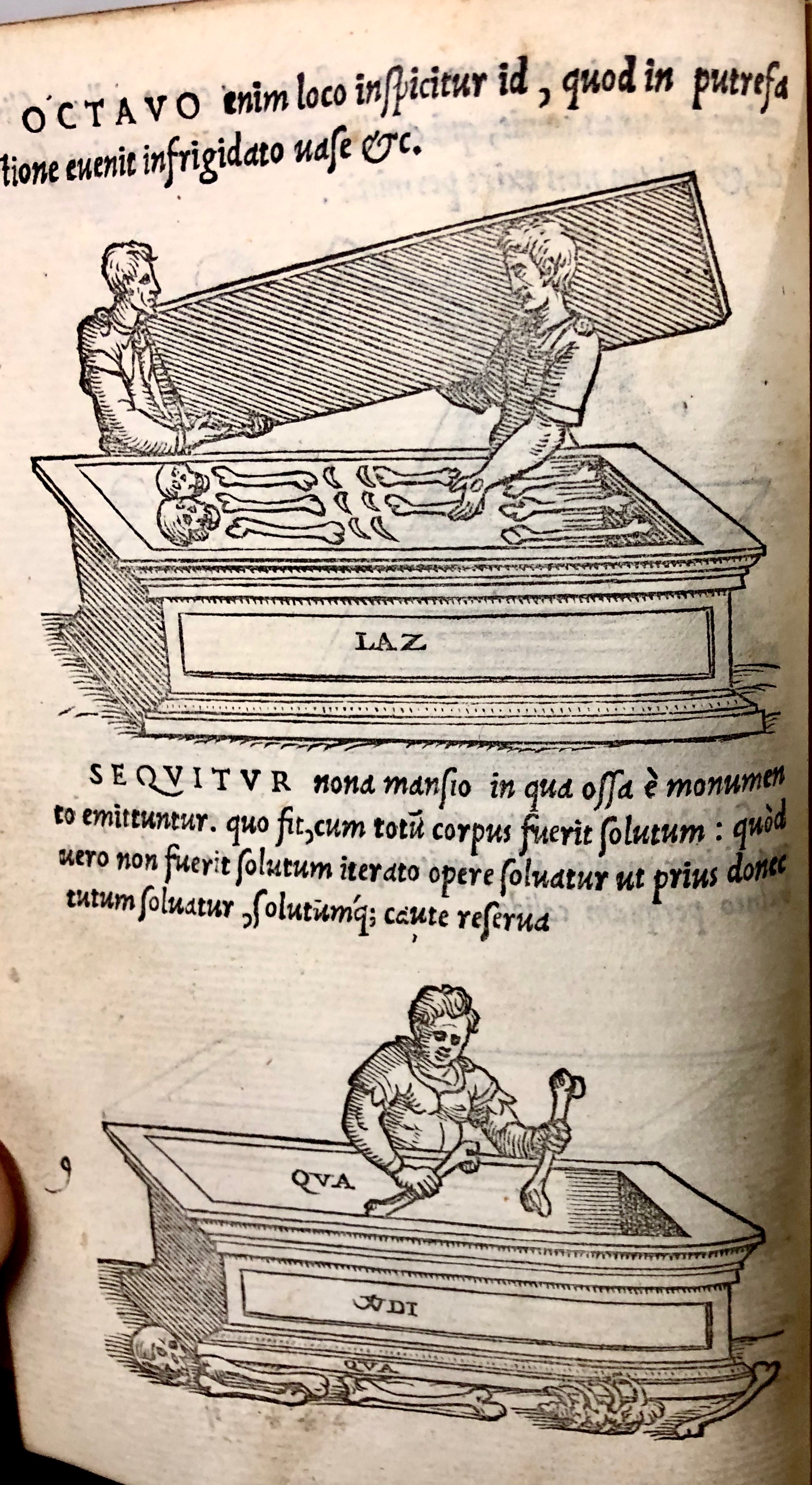

Conversely, a surprising observation of this book is the lack of internal decoration with very few woodcuts used. The same few woodcuts are repetitively used, suggesting that although this book was impressive externally the expense was spared internally. This contrasts with the 1577 edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles at the British Library which has many elaborate woodcuts depicting important monarchs and historical events that are not evident in the Templeman Library’s edition. The reason for this could be the lack of financial support behind the 1587 edition. After Holinshed’s death in 1580, his successors had difficulty establishing financial support for continuing with the new edition. Woodcuts were expensive additions to a book and were often reused instead of new ones being commissioned to keep costs down. This lack of financial means may explain the sparse use and recycling of a few styles of woodcuts in this copy of The Chronicles.

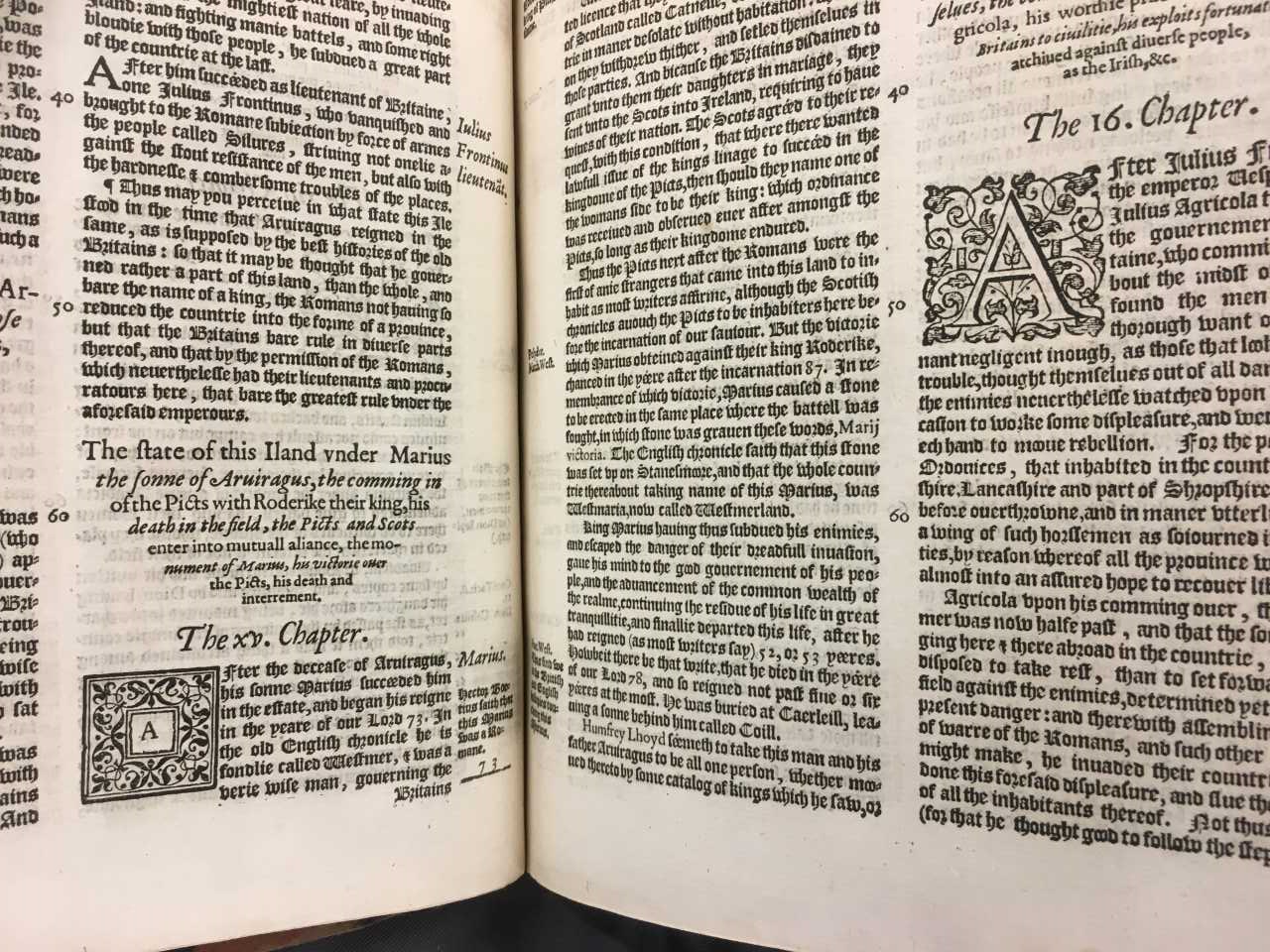

Example of the recycling and inconsistent use of letter woodcuts in the 1587 edition of The Holinshed Chronicles

Example of the recycling and inconsistent use of letter woodcuts in the 1587 edition of The Holinshed Chronicles.

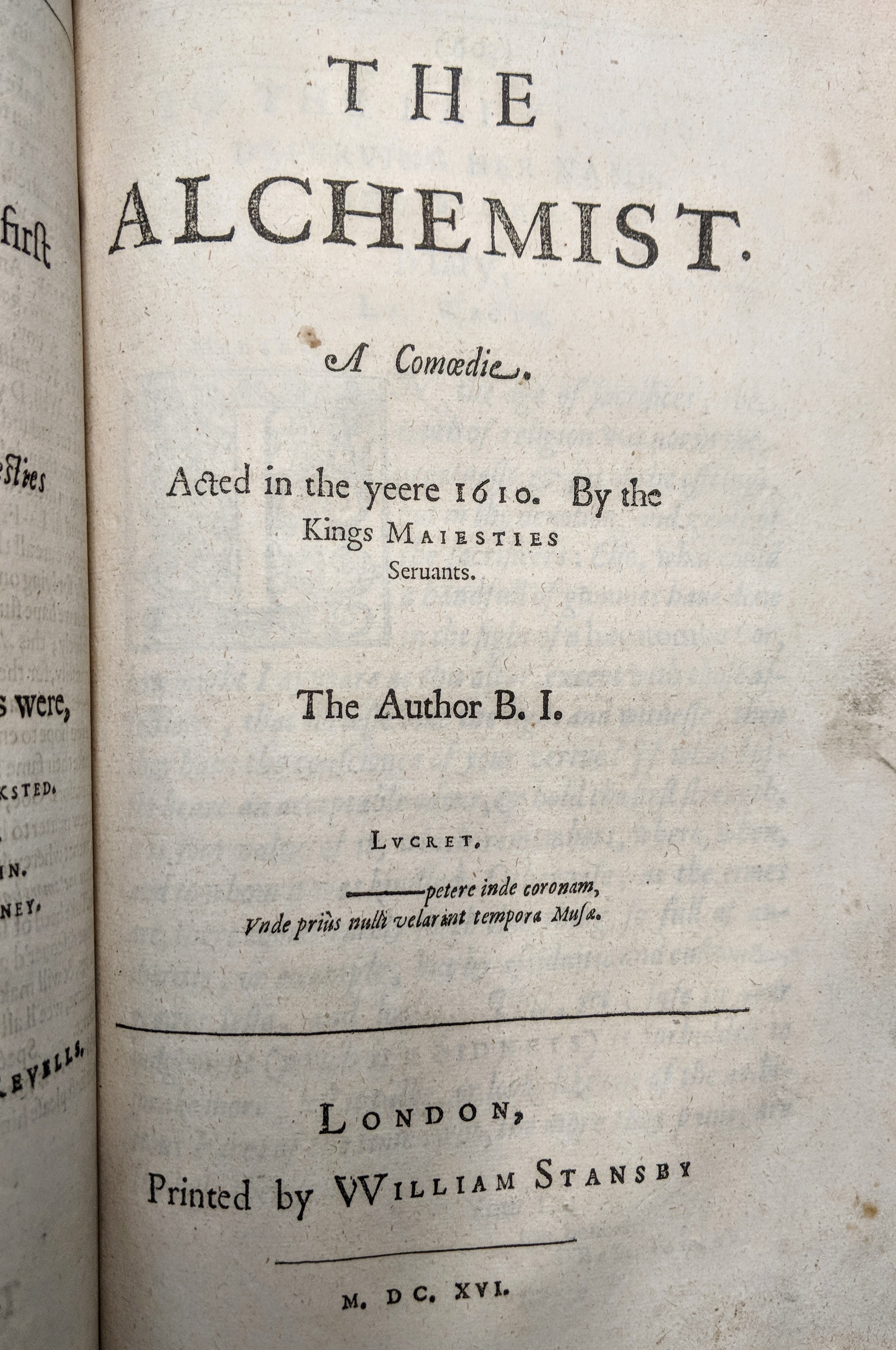

Example of the intricate woodcuts present in the 1577 edition of The Holinshed Chronicles which are absent in the 1587 edition (British Library)

From studying the ‘Historie of Scotland’ section, it is interesting that the story of Gathelus and Scota is present followed by detailed descriptions of the early Scottish kings. This mythical tale of the origins of Scotland contrasts with the section on England’s history, where the tale of Brutus explains the ancient history of the British Isles by stating Brutus’ son Albanactus was the first king of Scotland. However, the Albanactus and Brutus tale does not appear in the Scottish history section, demonstrating one of the many contradictions which exist within the book.

There is a general lack of public awareness of the Holinshed’s Chronicles despite its importance in detailing the history and mythology of the British Isles. However, the book remains a significant example of the emergence of a shared ‘British’ history and identity at the end of the sixteenth-century. The sixteenth century was a time of ‘British’ mythological history being used as propaganda in both England and Scotland, with competing national claims on ‘owning’ historical heroes. The inclusion of aspects of this mythological history in the collection suggests the importance of these stories in Scottish and English national identities and that Holinshed’s Chronicles allowed readers to explore these ‘histories’ in combination.

The Chronicles was also published in the context of growing awareness in England that a Scottish king may inherit the English throne. This possibility first appeared with the marriage of James IV and Margaret Tudor in 1503 and persisted throughout the sixteenth-century, especially during Elizabeth I’s reign, possibly explaining why Holinshed decided to collate works on England and Scotland together in his first edition in 1577. By 1587, it was believed that James VI would inherit the English throne after Elizabeth, and so both kingdoms and their histories would become one. Perhaps the inclusion of both England and Scotland in this collection is therefore significant in showing the growing belief in the late sixteenth-century that the island of Britain as we know it today was becoming a shared space and that therefore a single collation of their histories was necessary. If so, this book is important in showing how these ideas of Britain were viewed at the time.

To conclude, Holinshed’s Chronicles is an important book in illustrating how national histories and identities were perceived in the sixteenth-century. The decision to include both Scottish and English histories in one book demonstrates a broader thematic emergence of a shared British history and identity in the sixteenth-century which arose from the possibility of both realms falling under a single monarch. Therefore, this book as an object has wider significance for early British history than just what is written inside. Further analysis of this book should consider the reason why the elaborate woodcuts of 1577 do not appear in this edition; was it due to cost efficiencies or instead a consequence of the censorship which occurred in the late 1580s? Regardless of the lack of woodcuts, this copy of Holinshed’s Chronicles is a beautiful example of sixteenth-century literature which deserves wider awareness amongst the British public.

The copies of Holinshed’s Chronicles held in Special Collections & Archives are on loan to us via the Marlowe Society.

Bibliography:

- Clegg, Cyndia Susan; ‘Raphael Holinshed’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Available from: http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-13505#odnb-9780198614128-e-13505-div1-d196067e361 [Accessed 22/10/2018].

- Early English Books Online, Available at: https://eebo.chadwyck.com/search [Accessed 19/10/2018].

- Frenee, Samantha; ‘Warrior Queens in Holinshed’s Chronicles’, Journal of Medieval and Humanist Studies, 23(1) (2012) [Online] Available at: https://journals.openedition.org/crm/12859?lang=en [Accessed 25/10/2018].

- Holinshed, Raphael; Wolfe, Reyner; Stanihurst, Richard; Harrison, William; and Campion, Edmund; Holinshed’s Chronicles: The Firste Volume of the Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande, The British Library, (1577) Available from: https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/holinsheds-chronicles-1577 [Accessed 23/10/2018].

- Holinshed, Raphael, et al; Holinshed Chronicles: The First and Second Volumes of Chronicles, The University of Kent Special Collections, (1587).

- Kastan, David Scott; and Pratt, Aaron T; ‘Printers, Publishers, and the Chronicles as Artefact’, In: The Oxford Handbook of Holinshed’s Chronicles, Eds.: Felicity Heal, Ian W. Archer, and Paulina Kewes, (2013) Available from; http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com.chain.kent.ac.uk/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199565757.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199565757-e-2 [Accessed 25/10/2018] pp.1-27.

- Mason, Roger; ‘Scotland’, In: The Oxford Handbook of Holinshed’s Chronicles, Eds.: Felicity Heal, Ian W. Archer, and Paulina Kewes, (2013) Available from: http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com.chain.kent.ac.uk/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199565757.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199565757-e-38 [Accessed 25/10/2018] pp.1-18.

- Royan, Nicola; ‘Hector Boece’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Available from: http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-2760?rskey=J0aiDe&result=1 [Accessed 24/10/2018].

- Schwyzer, Philip; ‘Archipelagic History’, In: The Oxford Handbook of Holinshed’s Chronicles, Eds.: Felicity Heal, Ian W. Archer, and Paulina Kewes, (2013) Available from: http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com.chain.kent.ac.uk/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199565757.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199565757-e-35 [Accessed 25/10/2018] pp.1-18.

- The Holinshed Project, Available from: http://www.cems.ox.ac.uk/holinshed/ [Accessed 20/10/2018].

- University of Kent Special Collections Website, Available from: https://www.kent.ac.uk/library/specialcollections/ [Accessed 26/10/2018].

![Step ten: [Complex instructions for turning bones into purified water, involving subjecting some to heat until they turn black and repeating this until water is acquired] From 'Pretiosa margarita : novella de thesauro, ac pretiosissimo philosophorum lapide' by Giano Lacinio, 1546, Venice. (Maddison Collection 2B7, F10528400)](http://blogs.kent.ac.uk/specialcollections/files/2018/07/F10528400f.jpg)