Hazel has recently been working on our Pettingell Collection of Victorian manuscript prompt copies, which includes the holograph of playwrights such as Dion Boucicault, Charles Hazlewood and G. D. Pitt. Many of these prompt copies, handwritten playscripts with multiple annotations relating to staging, scenery and production, came from the Britannia Theatre, Hoxton, and are annotated by Frederick Wilton, the Britannia’s stage manager during the latter half of the nineteenth century. These copies arguably offer more realistic evidence about what was being performed on the Britannia’s stage than the copies which were sent to the Lord Chamberlain to be passed as fit for the stage (censorship on the British stage was only abolished in 1968). These copes are now held by the British Library as the Lord Chamberlain’s Plays.

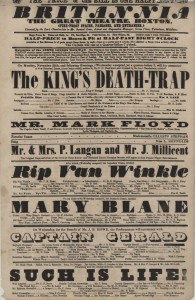

In the course of checking the status of these manuscripts, Hazel came across some overhead projector slides of playbills advertising ‘Varney the Vampire’, which led to investigation of where these should fit with the collection. As usual, in Special Collections, a straightforward task became something of a voyage of discovery; I’ve tried to summarise some of our findings here.

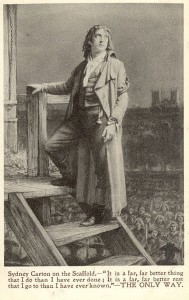

Vampire literature became popular in the early eighteenth century, although the first real mention of a vampire in English fiction occurred in 1797 with Robert Southey’s poem Thalaba the Destroyer. During the nineteenth century, the popularity of vampire fiction was still strong; Varney the Vampire; or, the Feast of Blood first appeared as a serialised ‘penny dreadful’ in 1845 and is attributed to James Malcolm Rymer. It was of epic length; when published as a book in 1847 it had over 200 chapters and almost 667,000 words. It was this tale which provided some of the most iconic pieces of vampiric lore to later writers of Gothic fiction, for example Varney’s fangs, hypnotic powers and superhuman strength. However, Varney had no problems with sunlight, crosses or garlic. Varney also represents a creature who is a slave to his condition, finding his vampirism repellent but unable to escape it. This idea of the reluctant vampire has been echoed in fiction ever since.

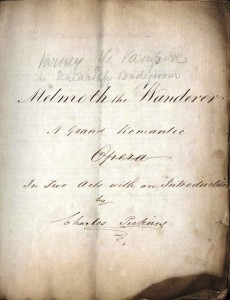

Varney was incredibly popular with his peers and was adapted for the stage (I can only assume in a shortened version). Another playscript which we hold (in manuscript prompt copy and printed text) is Melmoth the Wanderer, based upon Charles Robert Maturin’s 1820 novel. Although Maturin was commenting on contemporary society through this novel, it also contains some of the hallmarks of Gothic literature. In this novel, Melmoth makes a pact with the Devil to live for 150 years, and spends his life trying to find someone to make the payment for him. This, too, is an epically long tale, setting stories within stories and ranging between the New World and Europe. The connection between Melmoth and Varney? Well, it sounds a bit tenuous to me, but our manuscript copy of Melmoth has an alternative title handwritten on the cover: Varney the Vampire or the Unearthly Bridegroom.

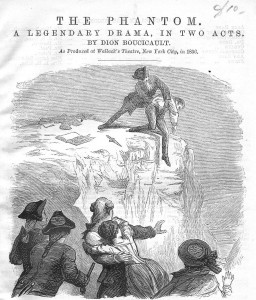

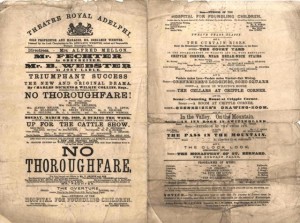

The popularity of vampires in performance was closely linked to the rise of melodrama. The first staged vampire melodrama was adapted by Charles Nodier from an unauthorised sequel to John William Polidori’s The Vampyre. (Incidentally, Polidori’s tale was inspired by Byron’s entry into the now infamous 1816 ghost story writing competition which also spawned Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.) Nodier’s version was then reworked and produced at the Lyceum Theatre in 1820, as The Vampire; or, the Bride of the Isles. Dion Boucicault also wrote a contribution to the genre, first produced at the Princess’s Theatre in 1852, entitled The Vampire: a Phantasm (later renamed The Phantom).

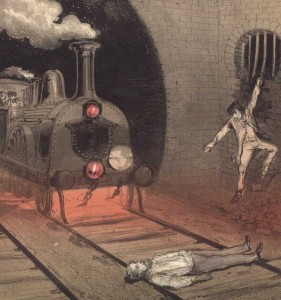

This interest in Gothic horror and the supernatural did not go unmarked by those in authority. On Tuesday 13 November 1888, Mr Channing reported to the House of Commons on the case of ‘two boys’ awaiting their trial for murder in Maidstone Gaol and how they

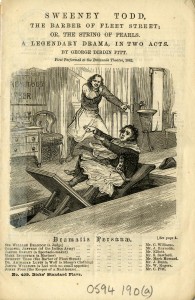

had been addicted by their own confession to reading of such books as “Dick Turpin”, “Varney the Vampire: or, the Feast of Blood” and “Sweeney Todd”…and that there was an enormous circulation of criminal literature among the young…these stories attractively written were widely circulated and read by enormous numbers of children, and instigated many of them to the commission of crime

The Times, 14 November 1888, p.6

In the end, we housed the overhead projector slide with a set of negatives of a prompt copy, entitled The Feast of Blood, which looks close enough to Varney’s original incarnation to make sense. But this little bit of research has shed a whole new light, for us, on Gothic and vampiric fiction (which no-one can fail to notice has made something of a comeback in the last few years). So it seems that maybe there isn’t anything new in concerns about the effects of popular fiction/culture on young people or in popular vampires (however reluctant).