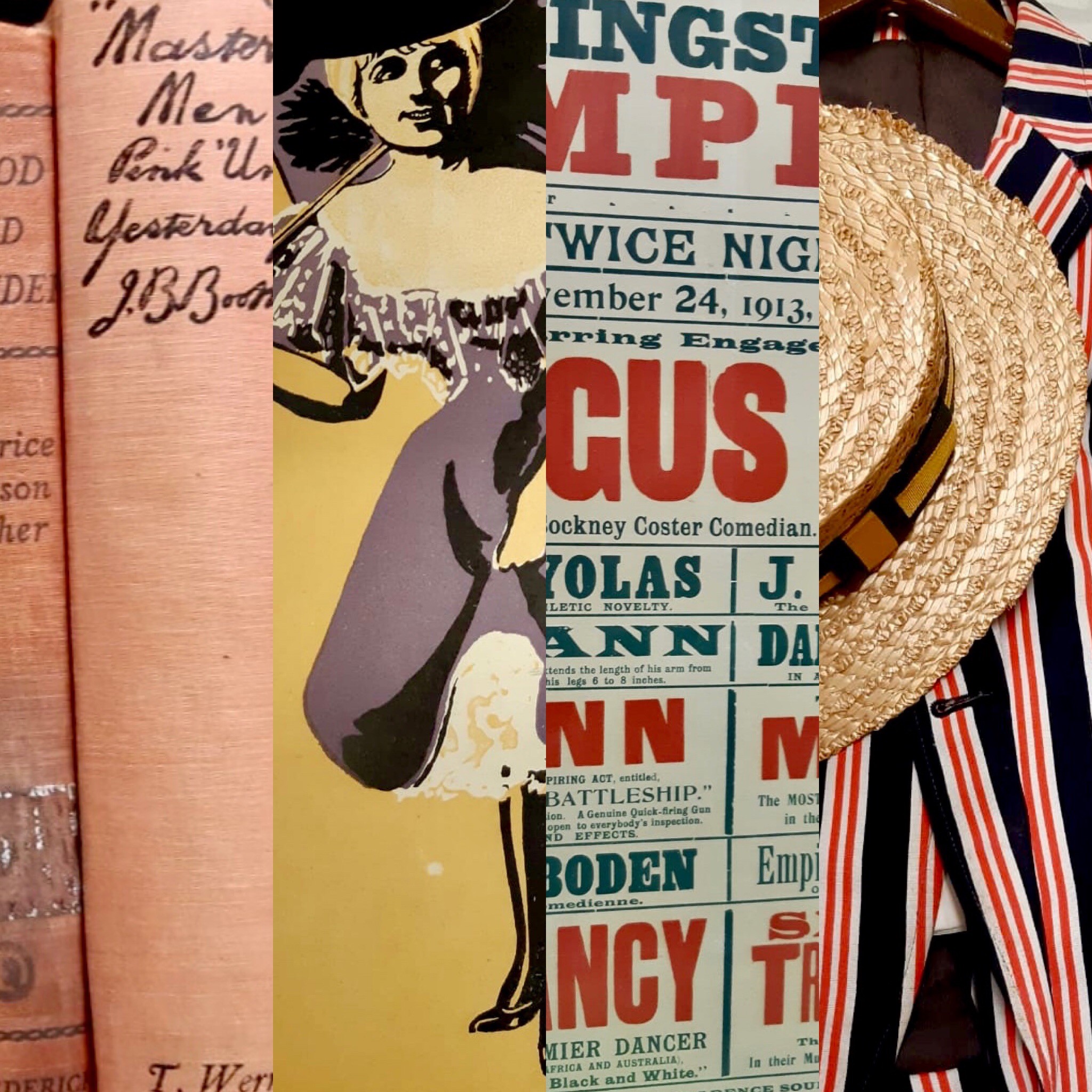

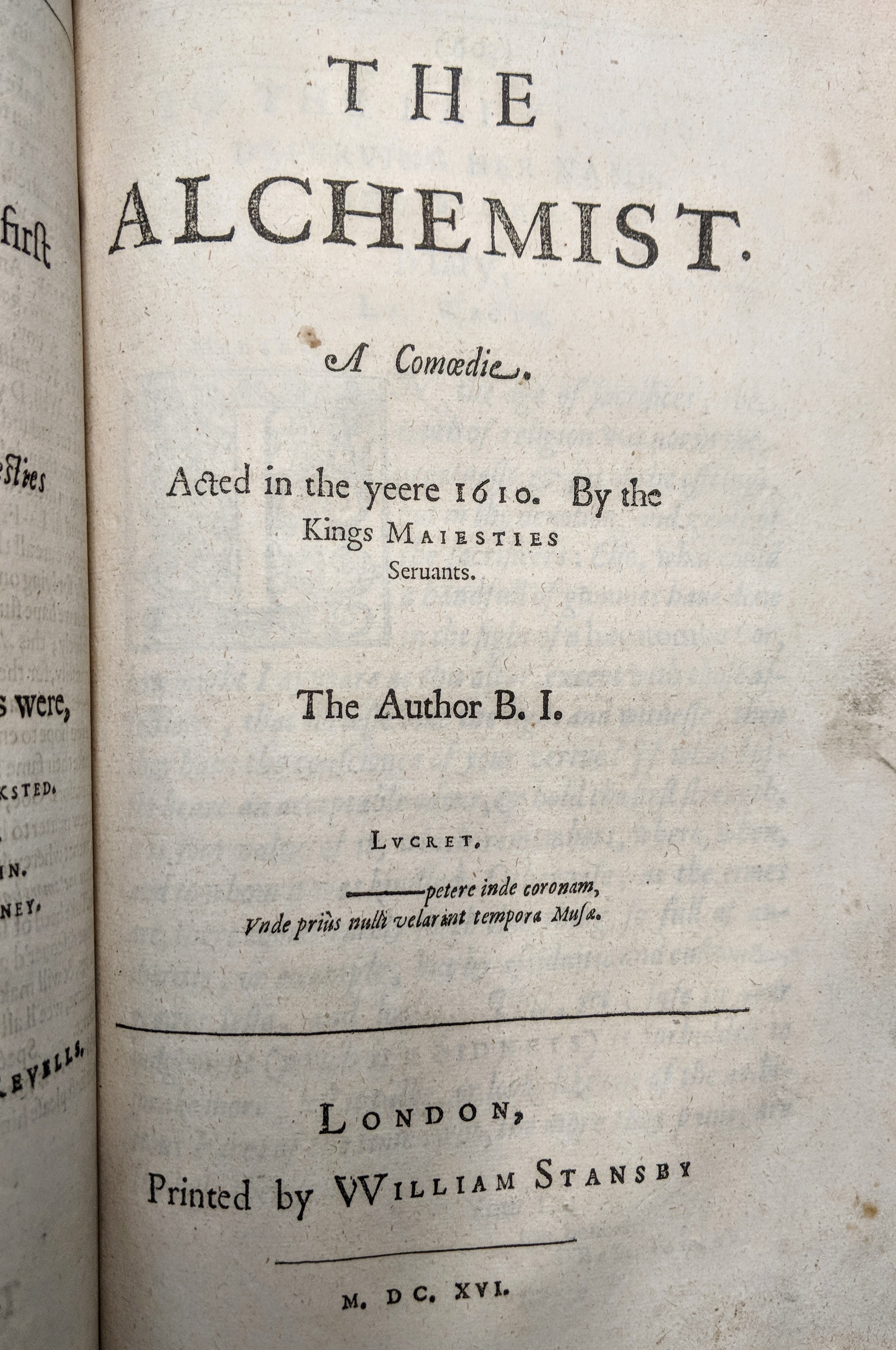

First performed in 1610 by the King’s Men, the acting company to which Shakespeare belonged, Ben Jonson’s The Alchemist is a satire centred around three con artists who use subterfuge, guile and wit to relieve targets of their belongings. Jonson makes no attempt to conceal his low opinion of alchemy and its practitioners, with the titular alchemist an obvious fraud and this makes it a useful springboard into thinking about alchemy in its historical context. The Templeman Special Collections and Archives holds a copy of Jonson’s First Folio from 1616 in its pre-1700 collection which contains the play and so in order to demonstrate how the Maddison collection could be useful for study and research beyond the history of science, we are going to use The Alchemist as a framing device for this week’s blog post.

Jo says we are not allowed to have favourites because it makes the other books sad. The Jonson Folio (Q C 616 Jon) is Philip’s favourite. Don’t tell Jo. Or the other books.

‘Alchemy is a pretty kind of game, / Somewhat like tricks o’ the cards, to cheat a man / With charming.’ (2.3.180-182, The Alchemist)

To the uninitiated, alchemy can seem a vague art form that seems to cover a range of random topics. Whilst researching for this post we read about people trying to turn base metals into gold or silver, about some trying to create a source of eternal life and others searching for ways to raise the dead. Alchemy has spanned a large number of fields in its history from supernatural and spiritualism to medicine and early chemistry but what many fail to realise is that alchemy was in fact an early science intent on answering many of the same questions we strive to answer today. It was only in the 1700s that a strong distinction between ‘alchemy’ and ‘chemistry’ was established; prior to this time that the study of both subjects was much more fluid.

The dragon-demon-sea monster thing is our spirit animal.

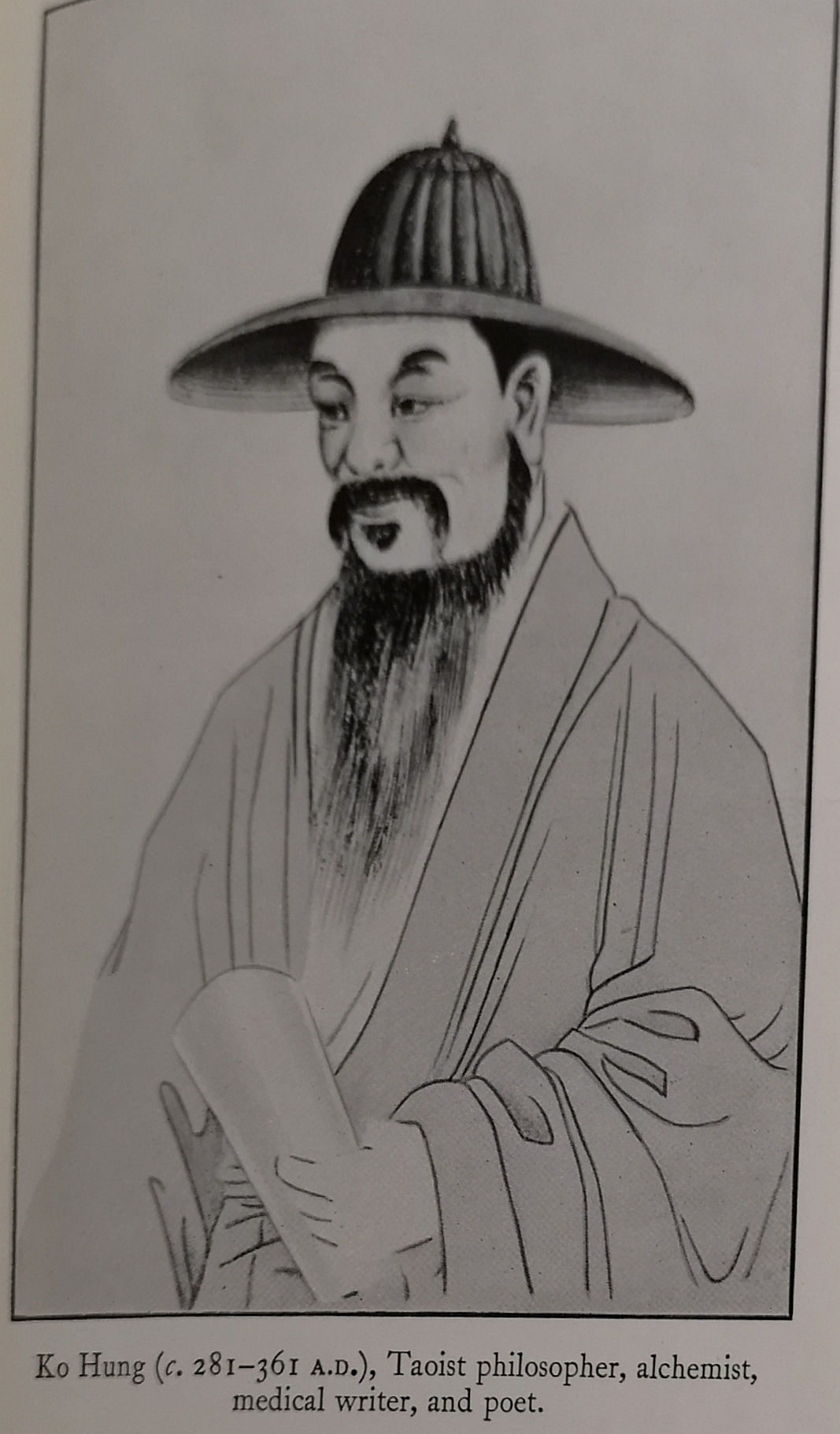

Alchemy has a long history, dating back to antiquity and it is possible to track its early modern evolution through the Maddison Collection in the form of dedicated volumes, notes and annotations, and handwritten recipes.The roots of Western alchemy are founded in the classical idea of the basic elements – fire, water, wind and earth – and it is primarily this Eurocentric alchemy which is covered in the Maddison Collection. Variant forms of alchemy have been practiced across the globe, particularly in the Middle East, China, and India. It is the various cultural and religious influences which make each strain of alchemy unique.

A taoist philosopher, alchemist, medical writer and poet, Ko Hung was the originator of first aid in traditional Chinese medicine.

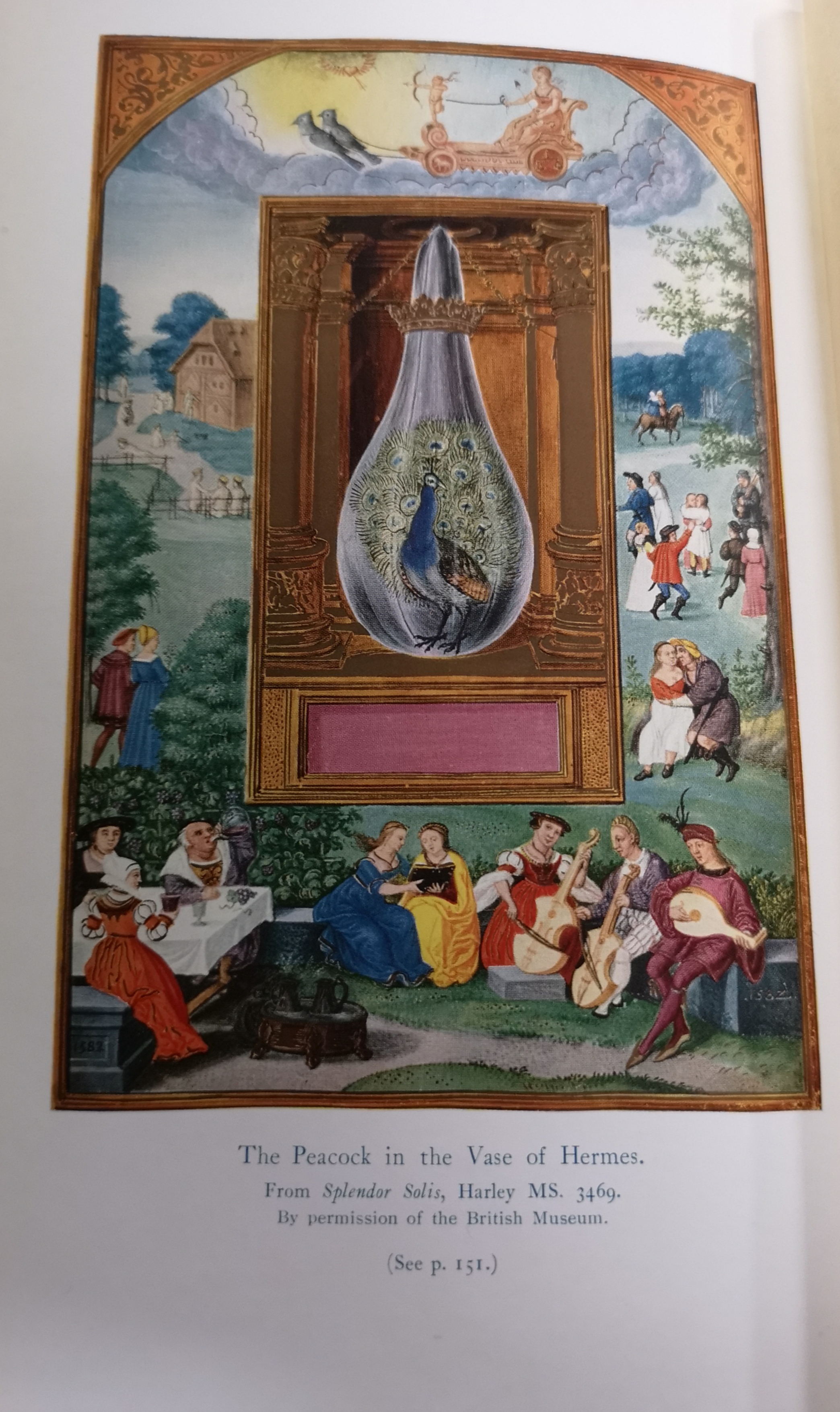

These aforementioned roots of alchemy are derived from the classical world and continued to evolve through the ages in Western Society by adopting and discarding knowledge from various influences. However, the core of alchemy always reflected its origins through its continued use of classical mythology as a communicative device. In multiple volumes within the collection the reader is able to see various illustrations utilised to express a concept or recipe in relation to alchemy, but to those unversed in identifying these alchemical signs these illustrations appear to be merely depictions of ancient myths and folklore.

This peacock is serving all kinds of fabulous perfection.

‘Nature doth first beget the imperfect, then/ Proceeds she to the perfect.’ (2.3.158-9, The Alchemist)

There were alchemists working across Europe through the medieval period into the early modern. The collection’s earliest works on alchemy come from Agrippa, a German polymath, legal scholar, physician and theologian,who was an important alchemist in the early sixteenth century. He is an interesting man to study, as during his career he turned away from the occult and focused much more his theological work, rejecting magic in his later life.

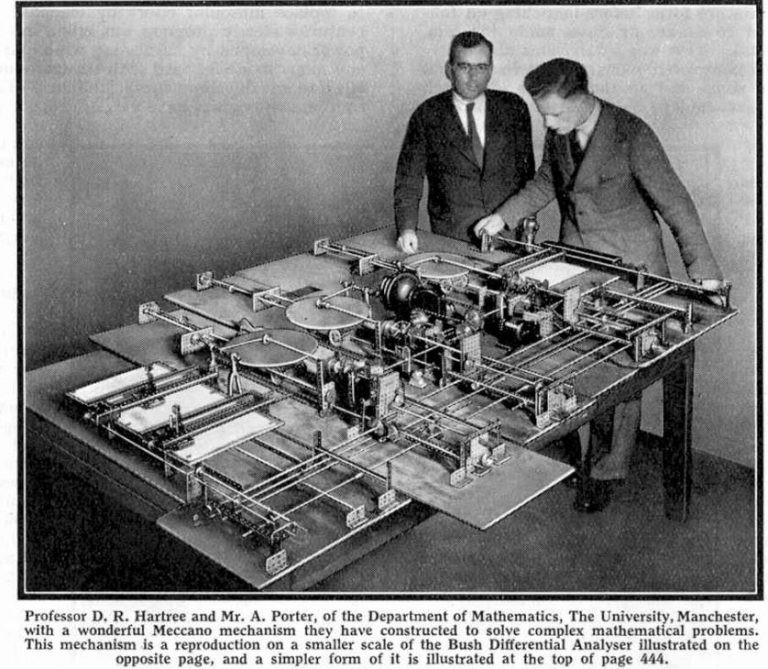

Just look at all those instruments! Agrippa’s getting the band back together.

Paracelsus is another influential figure in alchemical circles, also well represented. A respected physician, alchemist and astrologer during the German renaissance, Paracelsus is known as the father of toxicology, as well as being one of the first medical professors to use chemical and minerals in medicine. John Dee, Robert Boyle and Elias Ashmole were also important names in the history of alchemy and all of these alchemists have works related to them within the Maddison collection.

Guess who’s back, back, back. Back again, Boyle’s back! Tell a friend.

It is unsurprising that Boyle engaged in alchemy alongside his more conventional scientific research. Many regarded alchemists as great experimentalists, who engaged in complicated experiments, which they then documented and amended. Cleopatra the Alchemist was a Greek Egyptian alchemist from the 3rd century whom focused on practical alchemy and is considered to be the inventor of the Alembic, an early tool for analytical chemistry. She along with other alchemists such as Mary the Jewess focused on a school of alchemy which utilised complex apparatus for distillation and sublimation, important techniques still in use in the chemistry lab today. Cleopatra the Alchemist’s biggest claim to fame is as one of only four female alchemists who were supposedly able to produce the Philosopher’s Stone.

This was one method of distillation being utilised in 1653, which looks very similar to a modern day distillation technique! On a large drum sit 2 identical vessels, and in between them is a ventilation shaft allowing smoke to escape. The two vessels on the drum are connected by long thin spouts to two conical flasks,designed to receive the run off liquor.

‘I am the lord of the philosopher’s stone.’ (4.1.156, The Alchemist)

Twenty-first century readers may be more aware of alchemy than they realise. Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone placed alchemy front and centre in contemporary culture. Other references in popular culture include manga and anime Fullmetal Alchemist and fantasy video games, World of Warcraft and Final Fantasy, amongst countless more. F. Sherwood Taylor points out the misconception of alchemists as ‘magicians or wizards’ that is common to these modern representations, writing that ‘as far as we know the alchemists sought to accomplish their work by discovering and utilizing the laws of nature […] never […] by “magical processes”’ (p.1, The Alchemists: Founders of Modern Chemistry, F. Sherwood Taylor). The Philosopher’s Stone was one of the primary goals of alchemy. Supposedly the catalyst needed to turn base metals such as mercury, tin or iron into the noble metals, gold and silver, it was also theorised to cure illnesses and extend lifespan. Alchemists disagreed on just about every aspect of the stone; from what it symbolised to how it was created. What all alchemists did agree upon was that the Philosopher’s Stone was a tangible possibility and someone had managed to make and use it in the past. During our research we discovered a series of images related to transmutation that may be related to the Philosopher’s Stone. You can see those, with added captions, as part of the Adventures series here.

J K Rowling’s Half Blood Prince anyone?

‘If all you boast of your great art be true; / Sure, willing poverty lives most in you.’

(1-2, Epigrams VI, “To Alchemists”, Jonson)

The fortunes of alchemy and its practitioners waxed and waned through the centuries. Renaissance alchemist and thinker, John Dee is a prime example. A key adviser to Elizabeth I, after James I succeeded the throne Dee was accused of being a ‘Conjurer, or Caller, or Invocator of Divels, or damned Spirites’ and died impoverished.

Maddison Collection and it’s not Boyle! What a shock!

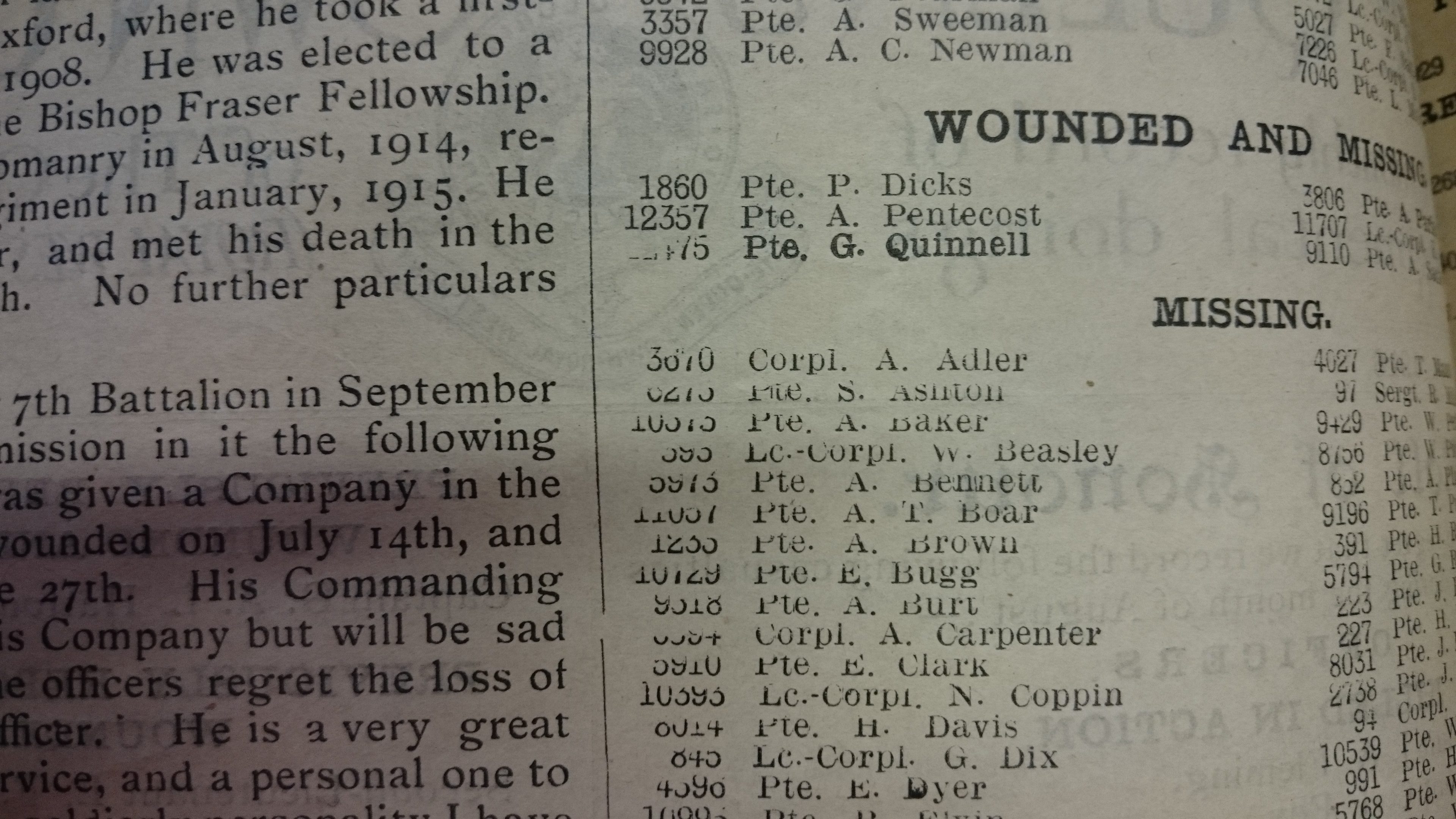

Most other alchemists did not suffer quite so dramatic a reversal of fortunes, but the legality of alchemy was dubious and throughout history it was often concealed in coded language or symbolic imagery. Renaissance legal scholar, Sir Edward Coke, wrote on its illegal status in The Third Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England (1644), citing the 1404 Act Against Multiplication, which forbade ‘multiplication […] That is, to change other metals into very Gold or Silver’ (Institutes, p.74). Robert Boyle campaigned to overturn this law and it was repealed in 1689.

As the eighteenth century wore on and the scientific method took hold, alchemy became increasingly discredited and chemists, wanting to distance themselves from alchemists, succeeded in separating the disciplines.The decline of alchemy in Europe was in conjunction with the rise of modern science, which placed a high significance on quantitative experimentation and which regarded the “ancient wisdom” so highly prized in alchemy as redundant and useless.

Starting with gold? I thought we were trying to make it! This is alchemy for the 1%.

Did alchemy work? Mostly not, but it was the forerunner to modern chemistry. Advancements in technology have now made some alchemical feats possible. For instance, it is now possible to turn lead into gold. It takes a chemist who knows what he is doing and a lot of time, energy and money, but changing lead to gold has been done. The method of doing so is nothing like what is recommended in the various alchemy books within the collection but the once scoffed at dream is now a possibility.

The Alchemist may treat its subject matter as a joke and its practitioners as charlatans but the tangible contribution of alchemy to scientific knowledge should not be undersold. As Sherwood Taylor notes, ‘the hopeless pursuit of the practical transmutation of metals was responsible for almost the whole of the development of chemical technique before the middle of the seventeenth century, and further led to the discovery of many important materials.’ (x, F. Sherwood Taylor) They may not have attained everlasting life or succeeded in transmuting lead to gold, but the alchemists did pave the way for their successors to develop modern scientific theory.

Tune in for the next blog post where we will be investigating the man behind the Maddison collection, R. E. W. Maddison!

Further reading

On Alchemy

John Read, Prelude to Chemistry (London: G. Bell and Sons Ltd., 1939) [Maddison 23B1]

J. S. Thompson, The Lure and Romance of Alchemy (London: George G. Harrap & Company Ltd., 1932) [Maddison 24A14]

Sherwood Taylor,The Alchemists: Founders of Modern Chemistry (London: William Heinemann Ltd, 1951) [Maddison 24A7]

Arthur Edward Waite, The Secret Tradition of Alchemy (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1926) [Maddison 24B20]

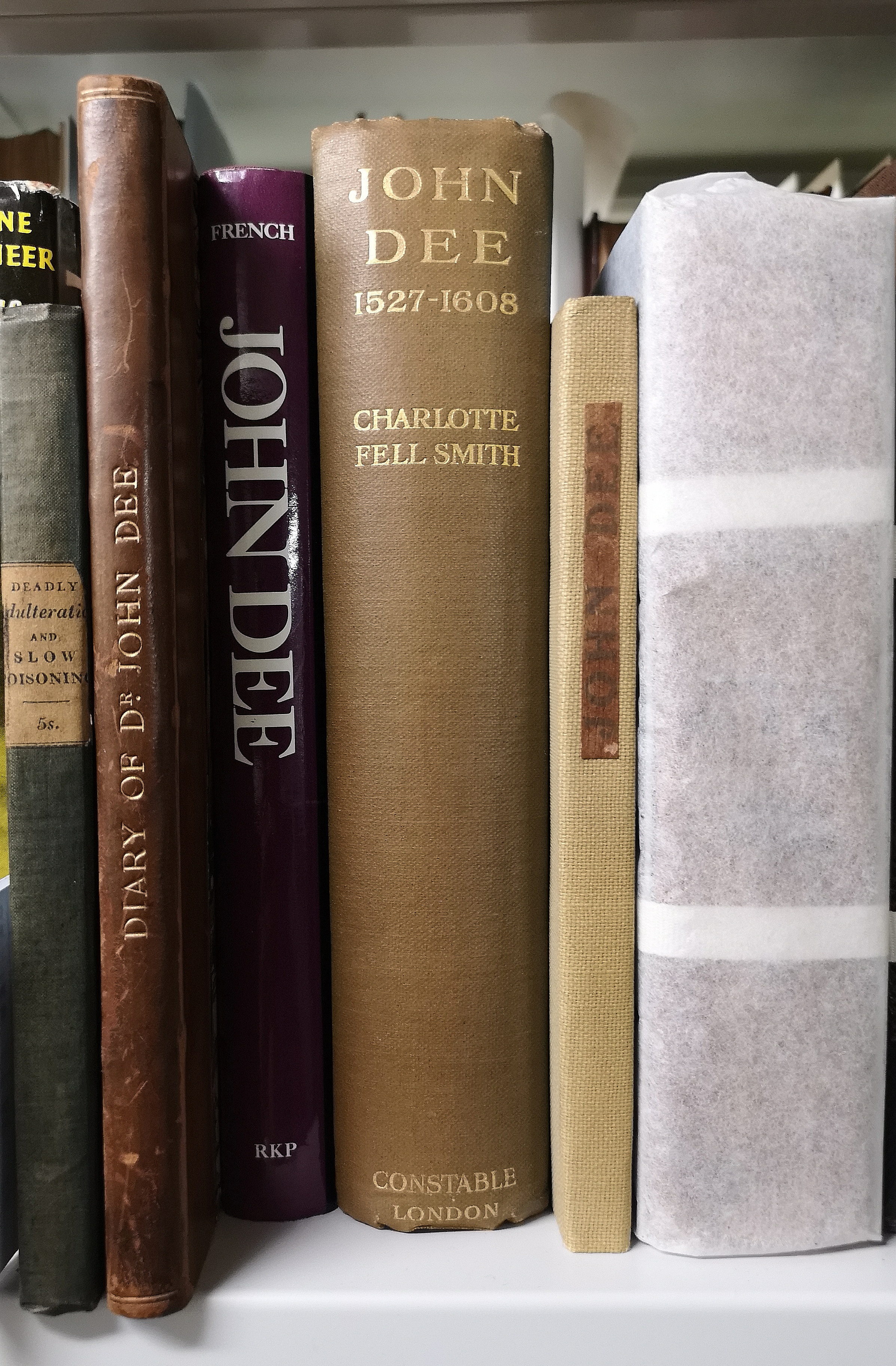

On John Dee

Charlotte Fell Smith, John Dee (1527-1608) (London: Constable, 1909) [Maddison 13C8]

Peter J. French, John Dee: The World of an Elizabethan Magus (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972) [Maddison 13C7]

Past exhibition at the Royal College of Physicians, 2016: ‘Scholar, Courtier, Magician: the lost library of John Dee’

On The Alchemist

Ben Jonson, The workes of Beniamin Jonson (London: W. Stansby, 1616) [Q C 616.JON]

Previously in Philip and Janee’s blog posts:

The honourable Robert Boyle; or, reaching Boyle-ing point?

Introduction; or, how do you solve a problem like the Maddison Collection?