It may no longer be summer (in fact, if anyone can remember a summer this year, I’ll be impressed), but that doesn’t have to stop us thinking about exotic locations and long, sunny holidays. Having said that, the latest stage of William Harris’ journey saw him reach Florence in November 1821 – where the temperatures were far from the heights he had enjoyed travelling across France since July.

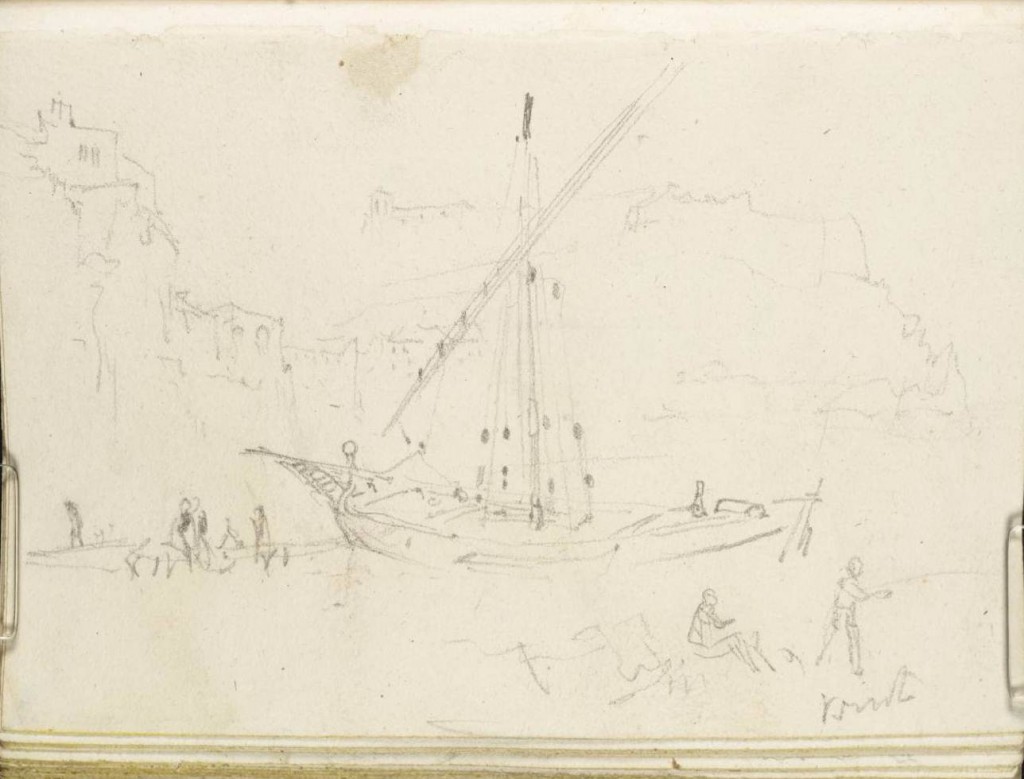

Sketch of a felucca by J. W. M. Turner (1828) (original held by the Tate)

In William’s previous letters to his father, he wrote about Dover, Calais, Paris and Mont Blanc. Having passed through Chamonix, climbed Mont Blanc and visited Geneva and Milan he then set sail on 25 October from Genoa. William and his friends sailed in a ‘felucca’, a traditional Mediterranean boat which could usually take around 10 passengers. On board, William and his three friends (Messrs. Brooks, Angell and Butts) met a Mr Edward Montagu, who was apparently educated at Cambridge and had spent the previous 8 months ‘cruising about the Mediterranean in a brig of war for his amusement’ – perhaps the nineteenth century gentleman’s equivalent of a late gap year.

As you may remember, William enjoyed his journey across the English Channel, although several other passengers were violently ill. His cruise from Genoa proved to be ‘a very pleasant little voyage’, despite the lack of comfort on the boat and some delays on the way. In the gulf of Spezia, the wind had been high and the sailors had taken on ballast – but by noon the sea was calm; the felucca ‘lay as a log on the surface of the ocean in sight of the celebrated marble quarries of Carrara’. ‘The sea agrees with me very well’, William wrote cheerfully.

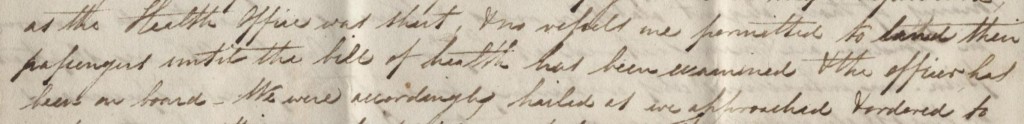

The architects entered entered the port of Leghorn at 9 in the evening, where, since the Health Office was closed, the group had to sleep a second night on the deck of the small boat. William explained,

“…no vessels are permitted to land their passengers until the bill of health has been examined and the officer has been on board”

The spread of diseases such as plague and yellow fever led to increasingly strict regulation by the British government during the eighteenth century; in 1752 the Levantine trade regulation act introduced a severe quarentine clause to traders in the area. These regulations became firmer in the ensuing decades, with a new act in 1805 and an enquiry in 1823-1824. Perhaps the all of these acts and regulations gave men like William, who was ‘compelled to pass a second night upon deck’, the feeling that the law makers were imposing unneccesary bars on their travel and trade. After the influx of cholera to Britain was not prevented by quarentine in the early nineteenth century, the practice largely disappeared from the British Isles.

The spread of diseases such as plague and yellow fever led to increasingly strict regulation by the British government during the eighteenth century; in 1752 the Levantine trade regulation act introduced a severe quarentine clause to traders in the area. These regulations became firmer in the ensuing decades, with a new act in 1805 and an enquiry in 1823-1824. Perhaps the all of these acts and regulations gave men like William, who was ‘compelled to pass a second night upon deck’, the feeling that the law makers were imposing unneccesary bars on their travel and trade. After the influx of cholera to Britain was not prevented by quarentine in the early nineteenth century, the practice largely disappeared from the British Isles.

Once he was able to enter the port, William found that he like Livorno, in the main. He approved of the “fine square and streets paved with longe [sic] flag stones laid diagonally and roughly tooled to prevent horses from slipping” and the considerable trade carried out in the town – “upward of 50 sail of British merchantmen were there”. The architects also discovered an English cemetery in the town, which William praised as being the neatest he had ever seen, apart from Pere-la-Chaise in Paris. “Tis planted with cypress trees casting a mournful shade,” he wrote poetically, adding that “many of the alabaster vases and chimney ornaments so numerous in London” were made in Leghorn.

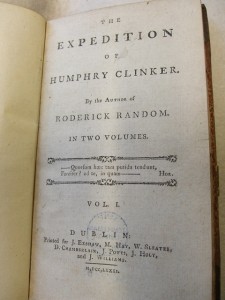

‘The Expedition of Humphrey Clinker’ was Smollett’s last novel.

The production of these ornaments was not the town’s final claim to fame for these travellers: in the English cemetery, they found a tomb to the memory of Tobias Smollett who had died in Leghorn in 1771 after retiring to Italy from his native Scotland. Smollett was a popular writer in the eighteenth century, who later alledgedly influenced Charles Dickens. The fact that William noted the tomb, along with his references in other letters to Byron and The Sentimental Journey by Laurence Sterne show that, like many other well educated gentleman of the day, he had studied British literature.

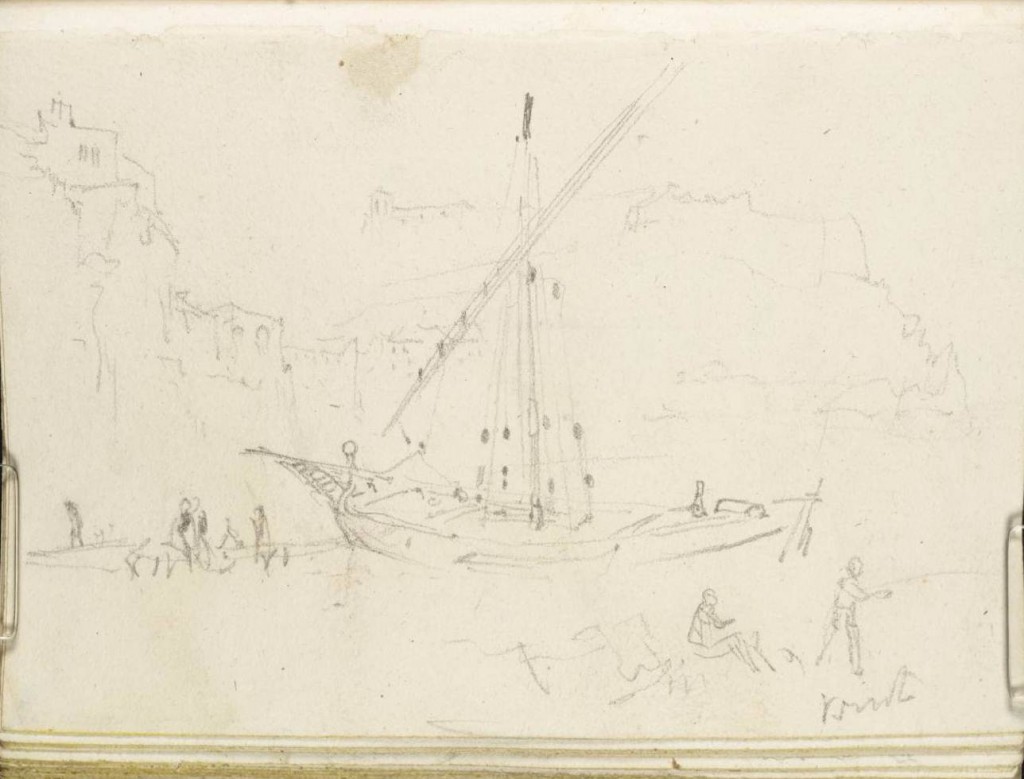

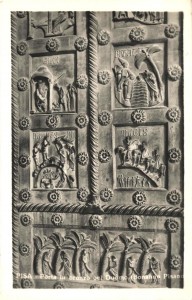

From Livorno, William and his friends then journeyed on to Pisa, where he was enraptured by the ‘Gotico-Tedesco’ (German Gothic) style of its architecture. He also noted

the most singular feature…is the celebrated leaning tower which actually overhands its foundation upwards of 13 feet and is almsot 180 high

Postcard showing 12th century doors to Pisa Cathedral (PC396)

In fact, the architects enjoyed Pisa so much that they prolonged their stay, ‘sketching and taking dimensions’. I hadn’t been aware of it before, but apparently nineteenth century architects spent a lot of time measuring things – from the number of young architects there appear to have been around the Mediterranean at William’s time, I think it’s impressive they all had the space to carry out their own measuring! There was, however, and important reason for Williams journey: improving his acuaintance with works of art.

After 6 days in Pisa, the group went on to Florence, arriving on 6 November. After Pisa’s hot sun, it was hard to adapt to the ‘very sharp’ wind and the frosty mornings. The onset of cold weather did, however, put an end to the annoyance of mosquitos, which William describes as ‘a very small kind of gnat’. The fact that he needed to describe the insects to his father suggests that they weren’t very prevelant in England – at least not in the fashionable part of London. Of course, we now know that mosquitos carry strains of malaria, which jeapordised the lives of many travellers…. But more on that later.

At the time when William and his friends were travelling, the modern nation of Italy didn’t exist. Instead, they travelled through various kingdoms on their way to Florence. In the terriroy of Lucca, William described

“Huge quantities of Indian corn are grown…may of the cottages were covered with large yellow ears suspended against the fronts to be dried by the sun”

Crossing the seperate territories involved passing numerous customs houses but to pass these swiftly, William advised, “the word ‘Inglese’ is really sufficient”. I doubt that such a self assured border crossing would be so easy now!

Crossing the seperate territories involved passing numerous customs houses but to pass these swiftly, William advised, “the word ‘Inglese’ is really sufficient”. I doubt that such a self assured border crossing would be so easy now!

Unfortunately, not everything has such an easy journey. As he travelled, William sent home the address of his bank at the next intended stop for any letters. At Florence, William blamed ‘the stupid banker’ for forwarding on a letter to his next intended stop, in Rome. The abashed banker ‘promise[d] to write immediately and rectify the mistake’. After William’s apparently straightforward experience of travel, and the talk of sending parcels and books across Europe, in an age before motorisation, it seems impressive that things didn’t go astray more often!

In Florence, William and his friends settled “at a ‘pension’ or boarding house at the Piazza Santa Maria Novella”, assuring his father that it only cost 45 shillings per head per week.

We sat down 13 [to the pension’s dinner tables] yesterday but that did not take away my appetite.

With all of the measuring he had still to do, it was probably a good thing that William was in such resolutely good health.

He closed his letter with an enquiry after Dick, the horse, and a summary of his expenditure to convince his father ‘not [to] imagine my dispursements have been more heavy than they actually are’. Concluding with ‘congratulations to the young married couple’ – another mystery to be solved – William set off to enjoy his weeks in Florence.

There, we leave him for the rest of November, until the small group of architects travelled south to spend the festive season in Rome, and discover all of the strange traditions which the ancient city could provide.

The landscape and the climate of the Switzerland, William explained, were largely the same as in England and ‘some of the cattle are as fine as our own’. After France, with its ‘endless straight roads’, the architectural eye found the ‘serpentine lines and hedges’ far more pleasing. William had little to say about Switzerland and his time spent in Geneva, only adding that there were delicious wild cranberries growing in the hedges on the road between Geneva and Sallanches. The journey from Geneva to the eventual arrival in Milan, however, offered plenty for William to write home about.

The landscape and the climate of the Switzerland, William explained, were largely the same as in England and ‘some of the cattle are as fine as our own’. After France, with its ‘endless straight roads’, the architectural eye found the ‘serpentine lines and hedges’ far more pleasing. William had little to say about Switzerland and his time spent in Geneva, only adding that there were delicious wild cranberries growing in the hedges on the road between Geneva and Sallanches. The journey from Geneva to the eventual arrival in Milan, however, offered plenty for William to write home about.