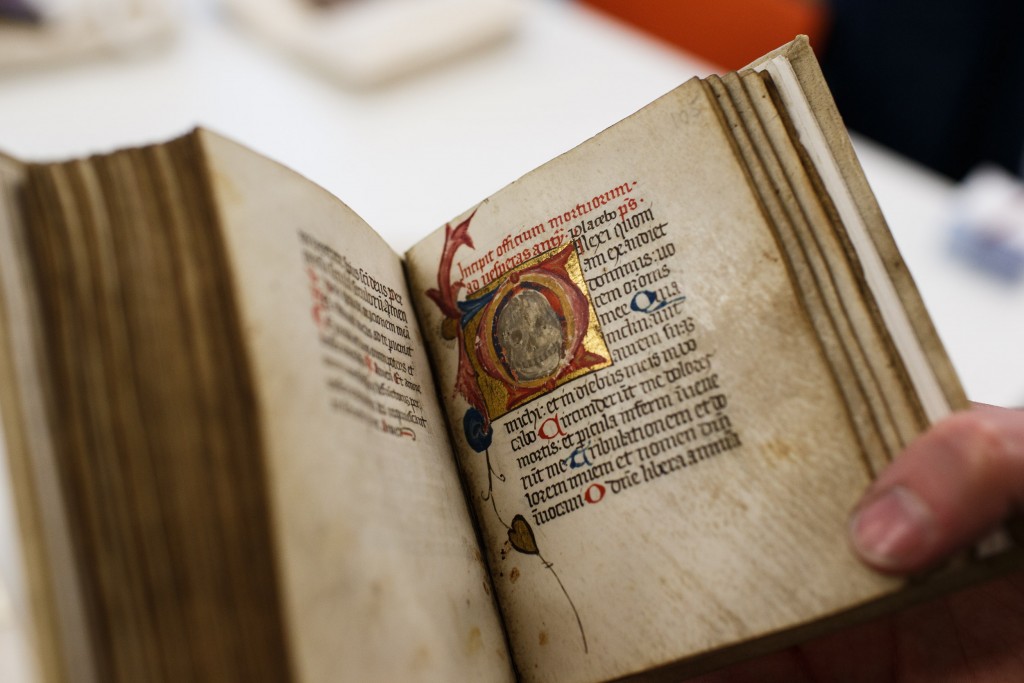

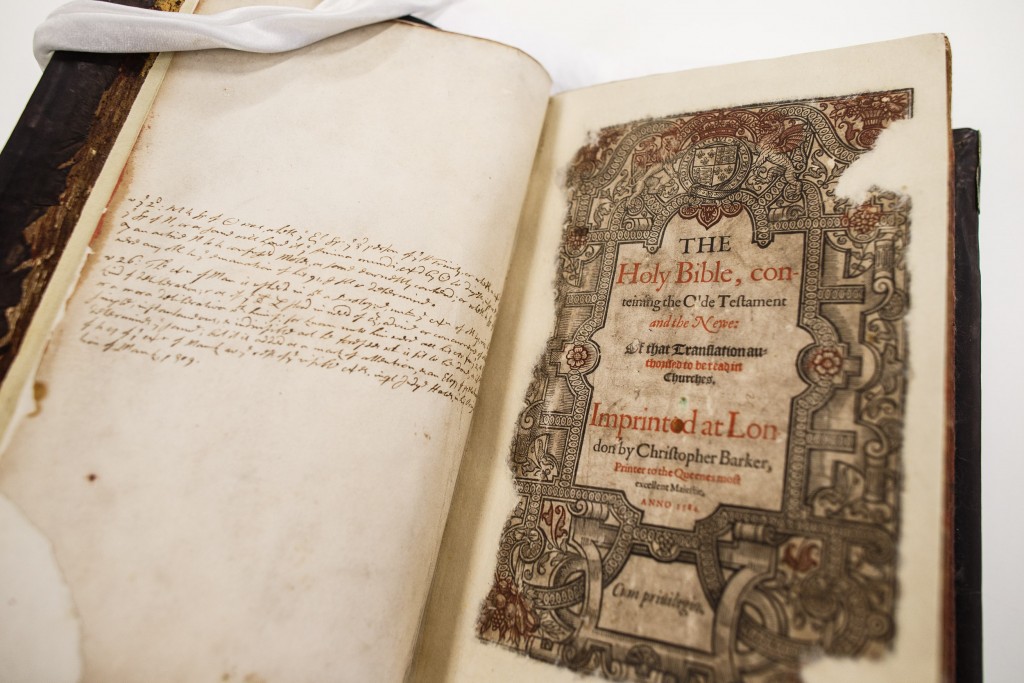

By walking in a labyrinth of ancient books and rare materials from the past, I’ve found some books which reminded me of my country and my homeland.

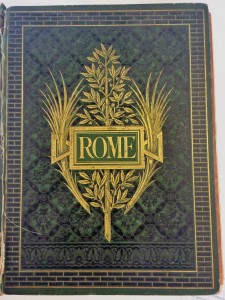

One of them was particularly eye-catching thanks to its size and its green cover full of detailed designs in gold and black. I knew it was about my Home because of the bright title marked on the centre of the cover: Rome. I could not control my instinct of curiosity and so I chose to read that one.

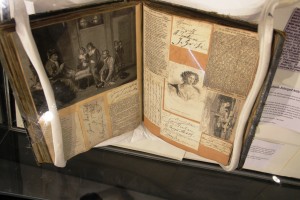

First of all I’ve found out that what I was holding in my hands was a book older than me, published in 1872 and written by Francis Wey. I thought it was going to be in Italian, but then I discovered it was in English and so I realised how much important traveling was, even in the ‘800s, and that human’s curiosity makes us travel seas and countries to be satisfied. And also, by going through some pages I’ve seen some really interesting illustrations: it was funny try to guess what part of Rome they were representing, and also it made me think about how the time changed those places during the years.

I had in my hands and in 552 pages one big wonderful city, my big wonderful city, and probably this is what made me choose the book at first sight.

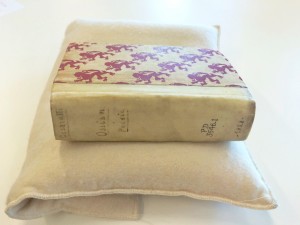

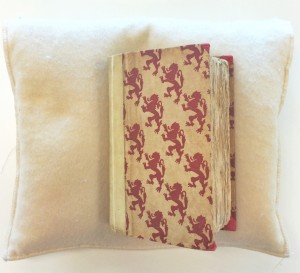

Another one that I decided to look at was a little book (quartos, I think they call them) from 1828 with a design of red lions on the front white cover made of a material that lasts well during the years and does not make the book look as older as it actually is [vellum]. The title, “Ossian Poesie”, was on the spine and it looked like someone else has written it on by using an old pen.

Unlike the book about Rome, this one was completely in Italian. I’ve found myself wondering about why there wasn’t any English in a book placed in a library in England, and I came to a conclusion about the fact that there might be some Italian students, or someone who was studying this language, that could have enjoyed it.

By reading some pages I understood the contest was about Irish royals, and it made me even more curious about why did an Italian writer, called Melchior Cesarotti, write about something which happened in another part of the planet.

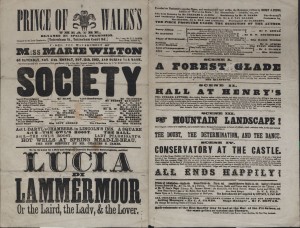

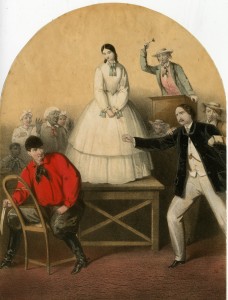

If it depended by me, I would have stayed around all those books for days and days, reading about everything from science to theatre, from geography to history.

Andrea Wlderk spent her Year 10 work experience placement with the Special Collections & Archives team this week. Having recently moved to Canterbury from Rome, she’s fluent in Italian, Spanish and English and wanted to know more about library work. Andrea learnt about how Special Collections departments are run and the activities we do, discovered our collections, shadowed meetings, was trained in basic conservation principles and worked in the stores with our volunteer team. Thank you so much, Andrea – we hope you had fun!