I thought I would let you all know that the new Special Collections and Archives Lecture Series was launched with great enthusiasm last night. Thanks to everyone who came along and enjoyed the lively talk – we were thrilled to see so many of you there.

John Butler talked about his experience of using the Hewlett Johnson Papers to write his book The Red Dean: the public and private faces of Hewlett Johnson. It was intriguing to learn about his ‘three star’ (with exclamation marks for extra special items) system which he used to identify key items while trawling through this vast archive when it was still in the very early stages of organisation. I think that Johnson himself would have been proud of John’s oration, particularly his recreation of Hewlett’s Maddison Square Gardens speech as he read out Alistair Cooke’s first Letter from America. John also outlined his contact with a Russian academic, Ludmilla Stern, who has been instrumental in bringing invaluable information about the shadowy Soviet organisation VOKS to Western researchers and his use of the National Archives to explore Johnson’s MI5 files. We are hugely grateful to John for taking on this daunting task of opening the new lecture series and hope that all of the rest of our lectures will be as enthusiastic and interesting.

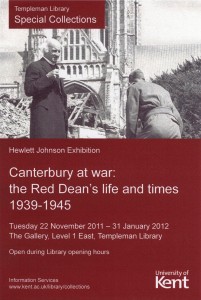

The exhibition, Canterbury at War: the Red Dean’s life and times 1939-1945, is now open in the Library Gallery space (left through the cafe in the Templeman Library, just outside the British Cartoon Archive). It will be running until January 31st during normal library opening hours and has already we’ve has some really positive feedback. Please do take the opportunity to have a look and let us know what you think.

It has been a challenge to set up the lecture series and the exhibition, but it’s been well worth the effort. Several thanks are due; firstly to Chris and Hazel for all of their hard work on the exhibition itself and to Nick and Jane of the Cartoon Archive for all of their advice and assistance with putting the exhibition up. Fran Williams and Angela Groth-Seary from IS Publishing have given us a huge amount of support in the printing and mounting of the display and also produced the publicity. Robin Armstrong-Viner and Karen Brayshaw were very willing volunteers on the night and we’d like to thank them for all of their help.

So, what next? Well, aside from the usual, we’re not finished with Johnson yet, as we plan to make the exhibition website live by Christmas – I’ll let you know how we get on with this. And, of course, there are two more lectures to go: Magic toads and twitching frogs: two natural history books from the seventeenth century which will be held in the Cathedral precincts and Doing damage from a distance: the art of British political cartooning which will be held in TR201 in the Templeman Library.

So our task of brining our collections out into the light of day has received an excellent boost – but we’re not finished yet!