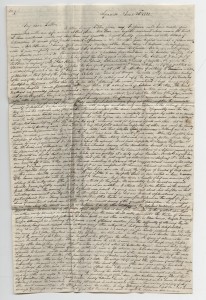

In the last post, I split William’s letter from Syracuse in two, since he (and I) had spent so much time talking about the delights of Taormina and the ‘original characters’ he discovered en route. As I mentioned, there was more than a little daredevil in these Georgian travellers, and the rest of William’s ninth letter is taken up with his ascent of Mount Etna. It seems this was one of the things which intrepid travellers tended to do at this period, but William has such an evocative writing stlye, I thought it would be a shame to cut the post short.

The shadow of Etna, stretching along in two distant lines meeting in a point might be plainly traced in the tranquil bosom of the ocean and slowly and majestically erecting itself in air, appeared embodied on the vapours and clouds suspended between earth and heaven, as the glorious luminary sank into the horizon.

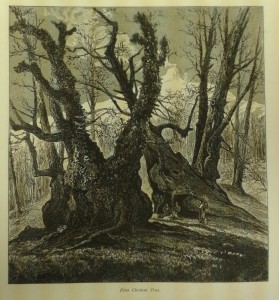

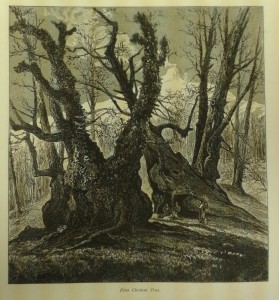

Illustration of ‘Etna Chestnut Trees’ from ‘Picturesque Europe’, p.200

As I mentioned last time, William had a journal with him, the entries from which he transcribed in his letter to his father – which we have in our collection. It’s unusual in that it offers a rather blow-by-blow account of the trip, including the specific dates. So we know that the group set off on 31st May 1822 at noon, having left Taormina for Nicolosi the day before. At this point, the group passed through a rather desolate area beneath a clear sky; finding that the sparse trees had been rather mutilated and were not particularly ‘fine’. Comparing the mountainside to the ‘Cultivated Regions’ lower down, which William had been singularly unimpressed with, he now considered those wooded regions ‘a paradise’. After meeting the obligitary mountain goats and being entertained with music from their herder, the group continued on:

The ascent gradually became more rapid and the keenness of the air became more sensible. Continuing our way through a country – perhaps ages long past smiling and fertile but now the empire of gloom and desolation, we finally lost all trace of vegetation and found ourselves every moment envelopped in the mist and clouds, which hastily swept along the sterile surface until they attained the loftiest ridgeof Etna, when they were instantly hurled away by a stronger and continuing wind to the mountain plains below, to commence another attempt equally futile to pass the forbidden ridge. The summit of the mountain (the grand crater) was occasionally visible through the clouds crossing each other in various directions. It was casting forth huge volumes of thick white sulphureous smoke.

Not to be put off by the obvious danger, nor the sudden cold and snow, the group went on to the ‘Casa Inglese’, a small house constructed, apparently, by a subscription of British officers in 1811. One can only assume that the ascent of Mount Etna was part of the package tour even in the early 19th century! Compared with today, however, the accomodation was basic:

It contains 3 chambers, the door opening into the centre room. Here the floor was covered with thick ice and in a closet was a mass of frozen snow at least 3 feet in height. We were lodged in one of the side rooms which had been divested of such benumbing companions and found a good charcoal fire which our avant-courier had prepared.

Leaving a man to prepare their dinner, William and his friends then went walkabout, to see the sunset and also marvel at the mysterious ‘Philosopher’s Tower’;

Some suppose it to have been erected for the reception of the Emperor Hadrian, when he visited this mountain; others imagine it to have been the mausoleum of some capricious being who wished his remains to be deposited in a place far remote from the haunts of man, but nothing is known with certainty.

Extract from Stockdale’s ‘Geography’, published in 1800 and perhaps an inspiration for William’s travels.

On their walk, it became clear how recently eruptions had been taking place; craters from the 1669 eruption were visible near Nicolosi, while the route to the Case Inglese was marked by a stream of lava from 1787, less than 50 years prior to William’s visit. The effect of the white snow alongside this ‘rich brown hue’ offered ‘a scene at once grand and perfectly novel’. The last eruption prior to their visit, it seems, was in 1819, but the dangers clearly did not concern the travellers as they enjoyed the scenery:

That side of the crater towards the Casa Inglese has two horns or points with a deep valley between them running down the side of the crater and partly filled with snow. In our lofty position we were the last human beings to whom the sun lent his rays in the same longitude and we were deprived of them a considerable time before they bad a short adieu to the towering pinnacles above. The shades of evening gradually stole along the plains till every remote object became indistinct. The clear silver moon shone in silent majesty and seemed to give token “of a goodly day to-morrow”. The air now became so piercingly cold, that we were glad to take shelter and close around our fire.

After a brief meal, and after the mules had been sent to the lower ground (to be watched over, presumably, by local guides), William and his friends tried to sleep. Using their saddles as pillows and wrapping themselves in their cloaks, in spite of all their adventuring spirit, did not work well. In any case, they rose at daybreak on the 1st June but found thick clouds swarming around the summit, so were unable to start the climb until 6am. In fact, William seems to have felt it rather less of a struggle than he had anticipated; ‘deceived by various exaggerated accounts we imagined it to be an Herculean task’, so losing the good weather they might have enjoyed had they begun the previous evening.

It took around an hour for the band of intrepid travellers to reach the summit, which was covered in thick smoke, with the cloud having rolled back in so that they ‘could distinguish only a few yards around us’. Reaching the ‘ne plus ultra’ seemed rather an anti-climx:

…thick vapourous smoke from every part which has so suffocating an effect that I scarcely hoped to be enabled to remain a single minute but on changing my position and thus getting to windward of it, the difficulty of breathing immediately left me. In some parts the ground was so hot under our feet it was impossible to remain there long. The sulphurous vapours were so dense and copious in the water, we could merely discern it had a rapid declination and judge of the distance by listening to the protracted noise occasioned by masses of stone rolled into it by the guide.

Of course, being men of the Enlightenment, it was not just the views which they had come to see. At the height of the volcano, they noticed a ‘varied grandeur of effects’, including the speed with which the clouds passed by, wrapping the little band in thick fog, unable to see one another while the land below was drenched in sunlight. From the summit, it also seemed as though the ocean ‘appeared to rise to our own level’.

We here observed a very curious effect produced by the sun beams, when now and then they shone through the clouds. Our shadows were cast on the vapours of the water and each of us saw his own enriched by a faint Iris of the hues of the rainbow and eccentric rays darting from it. We had observed a similar effect, but no Iris, from the shadow of the mountain on the vapours of the preceding evening, that is to say the eccentric rays alone.

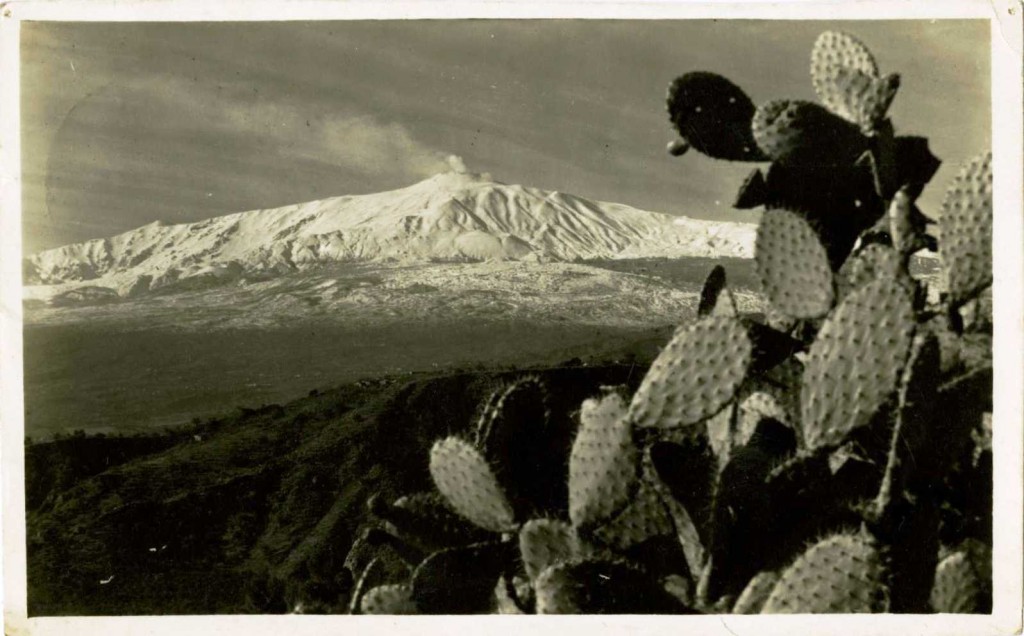

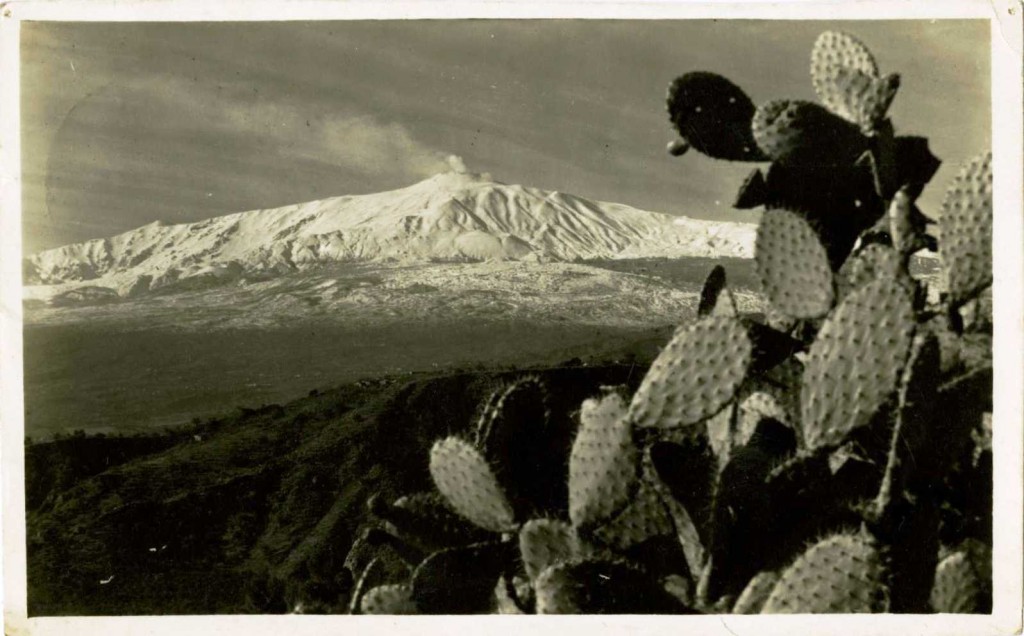

1930s postcard of Mount Etna, on which the volcano is described as “past all desription – BEAUTIFUL – early in the morning – with a blue sky & almond blossom”. From the Hewlett Johnson Collection.

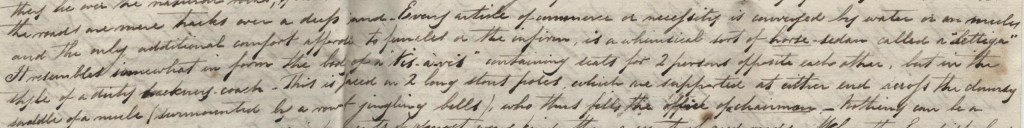

After two hours in the thin air and cold, the band descended to reach the Casa Inglese in half an hour, but were far from finished with the mountain. They decided to return to Nicolosi via the Valle di Bove so that they could see ‘the celebrated Chestnut of a Hundred Horse’ – the oldest known chestnut tree in the world. The cloud remained heavy during the descent, when they found themselves walking over the remains of two earlier eruptions – 1811 and two month long eruption of 1819, which had destroyed a significant portion of farmland. This area, William wrote, was ‘covered with ashes and wrapt in silence’, with the going hard, each footstep sinking them ‘a foot deep’ – ascent via this route was impossible, but the sights seem to have been worth the struggle. They passed a stream of lava from the latest eruption which were still smoking with sulphur. A little further on, the group paused to admire the view (and no doubt to get their collective breath back), but the guide warned them:

not to loiter on – as the masses of strata are apt to detach themselves and roll into the narrow valley below

After four hours, they came in sight of their goal, and another hour brought them to the Chestnut of a Hundred Horse – an impressive but apparently not entirely impressing sight.

It consists of 5 distinct trunks all very much decayed…but however one might be inclined to believe these several huge masses to have been formerly united (each…forms a noble tree) it required a greater degree of reliance on the tradition than we could summon…to feel convinced of such an apparent impossibility.

In spite of William and his companions doubting, the several thousand years’ old tree is apparently still connected to a single root system below ground, even though the trunks are now seperated above ground.

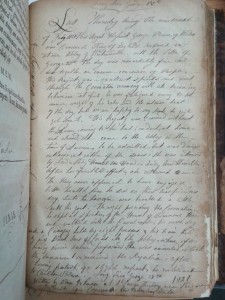

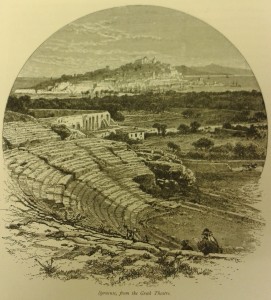

After their ‘day of contrasts’, William and his friends found lodgings in a nearby village for a well-earned rest, although they discovered their host ‘a profligate steward of our purses’ after presenting the extravagant bill. On returning to Nicolosi, their host was delighted to hear of their exploits and advised them that ‘our excursion…had never been undertaken by foreigners in his recollection’. From Nicolosi, the group journeyed on the Catania, then to Syracuse, where William and fellow architect Thomas Angell went back to their favourite task of measuring, this time the local Temple of Minerva and an ancient Greek theatre.

Illustration of ‘Syracuse, from the Greek Theatre’ from ‘Picturesque Europe’.

William closes his letter with an assurance that his expenses fall well within his allowance, and a plea for news from ‘Old England’. One of their number, Mr Butts, had returned to England earlier and William asked for news of his friends to be passed on, recalling their trip across the Mer de Glace at Chamonix and commenting that climbing Etna had been much easier. Perhaps he had become used to the excitement and hardship of travel, after a year roaming the Continent. From Syracuse, William and his friends journeyed on across Sicily, looking for adventure. I suspect that what they found was not what any of them were expecting… But that’s a tale for another time, and with three letters still left in this series, hopefully I’ll finish the story before it’s actually taken the length of William’s long trip!

enthusiasm for discovering more about his journey has diminished; in fact, the other day I was idly glancing through a holiday brochure and saw a package tour around Sicily, covering Mount Etna, Palermo, Siracusa and Taormina and got a bit over excited. No, this isn’t my planned holiday for this year (not at that price!) but this does follow the journey which William and his friends took nearly 200 years ago. In fact, it looks like William was part of the team which undertook some of the earliest work on these now very popular tourist destinations.

enthusiasm for discovering more about his journey has diminished; in fact, the other day I was idly glancing through a holiday brochure and saw a package tour around Sicily, covering Mount Etna, Palermo, Siracusa and Taormina and got a bit over excited. No, this isn’t my planned holiday for this year (not at that price!) but this does follow the journey which William and his friends took nearly 200 years ago. In fact, it looks like William was part of the team which undertook some of the earliest work on these now very popular tourist destinations.