It’s not uncommon that we’ve used this blog to look at how little things have changed over the past century – and sometimes more! Charlotte Daynton’s work looking at the Muggeridge Collections drew this out in terms of everyday objects she revealed in uncatalogued boxes of material, while a long time ago (or so it seems!), I was struck by the similarities between politics of the early twentieth century and that of today. Perhaps it’s just our nature to try to find links with the past (thought I wouldn’t necessarily argue that this happens more today than in previous generations) – it certainly reminds you that even if something is now in an archive, once it was a ‘working’ item, and meant a lot to its owner.

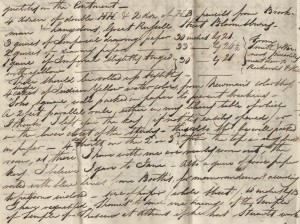

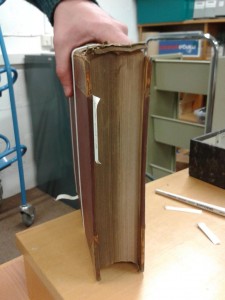

Historian Hugh Gault, currently working on the second part of his biography of Sir Howard Kingsley Wood, has drawn my attention to some interesting items in the press cuttings through which he’s been wading as part of his research. These particular cuttings are pasted into enormous scrapbooks which take at least two people to lift: quite why Wood had these created, or how he used them, remains a mystery. But what could be more relevant today than the ideas of preserving natural beauty spots, political debates in the media and the questionable ‘issue’ of ladette culture?

Few people can have failed to notice that we’re just a few weeks away from the next General Election – and it would have been hard to miss the issue of who should be included in the next round of televised political debates. While this has caused quite a stir in 2015, in 1933 there were claims that ‘independent’ views were being deliberately censored in upcoming wireless debates on the BBC. Three politicians (none particularly unknown to the Establishment), Winston Churchill, David Lloyd George and Austen Chamberlain, wrote to the Corporation complaining that, despite the assurance that ‘minorities should have their place’ in the radio debates, those not nominated by Party Whips were effectively being discriminated against (‘Politics on the Wireless’, The Times, 11 September 1933). J. H. Whitely, chairman of the BBC, responded by arguing that space necessitated a careful selection of speakers. He added that, while the Corporation had no desire to ‘curtail freedom of speech…it cannot guaranteed that…room will be found for the expression of all shades of opinion’.

Few people can have failed to notice that we’re just a few weeks away from the next General Election – and it would have been hard to miss the issue of who should be included in the next round of televised political debates. While this has caused quite a stir in 2015, in 1933 there were claims that ‘independent’ views were being deliberately censored in upcoming wireless debates on the BBC. Three politicians (none particularly unknown to the Establishment), Winston Churchill, David Lloyd George and Austen Chamberlain, wrote to the Corporation complaining that, despite the assurance that ‘minorities should have their place’ in the radio debates, those not nominated by Party Whips were effectively being discriminated against (‘Politics on the Wireless’, The Times, 11 September 1933). J. H. Whitely, chairman of the BBC, responded by arguing that space necessitated a careful selection of speakers. He added that, while the Corporation had no desire to ‘curtail freedom of speech…it cannot guaranteed that…room will be found for the expression of all shades of opinion’.

The complainants found this response unsatisfactory, responding via a letter subsequently published in The Times, that ‘a precedent is established’ which they considered would result in the ‘effective exclusion from the broadcast’ of anyone holding ‘non-official’ opinions.

In the same year, a different branch of the BBC, under the guidance of Wood as Post Master General, announced its ‘biggest drive against radio pirates’ (‘Biggest Drive Against Radio Pirates, Daily Mail, 25 September 1933). This would be undertaken by means of ‘new detector apparatus’ installed in detector vans and set on a pilot scheme from 1 October. The key intention of these new measures was to catch the ‘pirates’ who were listening to programmes without paying their license fee of 10 shillings a year. Wood himself championed these measures, according to an article in the Daily Mail, ‘realising that the autumn drive by the B.B.C. for better and brighter radio entertainments will attract thousands of new listeners…’

In the same year, a different branch of the BBC, under the guidance of Wood as Post Master General, announced its ‘biggest drive against radio pirates’ (‘Biggest Drive Against Radio Pirates, Daily Mail, 25 September 1933). This would be undertaken by means of ‘new detector apparatus’ installed in detector vans and set on a pilot scheme from 1 October. The key intention of these new measures was to catch the ‘pirates’ who were listening to programmes without paying their license fee of 10 shillings a year. Wood himself championed these measures, according to an article in the Daily Mail, ‘realising that the autumn drive by the B.B.C. for better and brighter radio entertainments will attract thousands of new listeners…’

The scale of this drive was expected to be monumental, beginning on the north-east coast, before spreading across the country. The article adds that, in the past, some had considered the detector vans ‘a gigantic bluff’, but quotes an unnamed source assuring readers that they should not ‘call’ the supposed bluff:

This so-called bluff will be an even more dangerous one to “call” than formerly, as engineers have for the past year been carrying out exhaustive experiments with new apparatus.

Advances in new technology were, of course, alarming to some, and nothing was so noticable as the impact on ‘England’s Beauties’ (‘Preserving England’s Beauties’, Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 6 September 1933). Wood felt a duty to preserve beauty spots such as the Peak District and the Derbyshire Dales, issuing instructions to his engineers putting up overhead wires to expand the reach of telephone systems advising them to ‘give careful consideration’ to any proposed lines which might ‘spoil a view’. Indeed, concerns had also been raised about the new telephone boxes: ‘originally designed for urban [settings], these boxes are not always appropriate in a village’. The bright red of the boxes was felt, by some, to be ‘out of harmony’ with its surroundings, and plans to paint some ‘a dull green colour’ had been put forward. It’s strange to think that the red phone box is often only seen in rural areas, now – if at all!

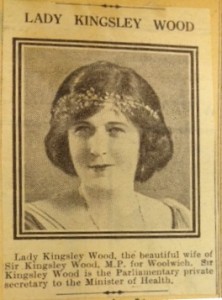

Agnes Wood, in 1923. Agnes was an independent woman prior to her marriage, and wrote articles to support her husband’s cause to new, female voters in 1918.

Finally, a perennial ‘problem’ has been the perception of the younger generation. In 1933, Wood was in his fifties, and the younger generation now coming to adulthood would have known little of the First World War through which their parents had lived. According to the journal ‘Queen’, there was disapproval of ‘modern girls’, supposedly ‘chiefly employed in drinking cocktails in nightclubs’ (untitled article, Queen, 20 December 1933). Given the changes in the legal and social status of women, particularly after women (over 30) were given the right to vote in 1917 and the vital role women played in the War, perhaps these ’employments’ were considered detrimental to this new-found status. However, Wood was reported as their ‘doughty champion’, saying:

The young woman of to-day…is no longer a clinging vine or the mental inferior and the dutiful handmaid of mere man. But she is self-reliant, tenacious and courageous, and is taking her part more than ever in the world’s work. I do not doubt that the younger generation will provide men and women able to rise to any emergency…. It is quite possible that they will do even better than their parents.

This generation of women would have been the first to grow up with the right to vote from the age of 21 (from 1928), unlike their predecessors who had fought for enfranchisement. It’s rather tragic to think that, six years after Wood’s ‘unquestionably true’ statement, this generation was indeed called upon to rise to an emergency, as their parents had been forced to, with the outbreak of another World War.

The Kingsley Wood Collection consists of 25 scrapbooks of press cuttings, four albums of photographs and a number of loose typescript materials. The first part of Hugh Gault’s biography of Sir Howard Kingsley Wood, ‘Making the Heavens Hum: Kingsley Wood and the Art of the Possible’ is available now; the second part is due to be published in 2017.