Many sides of Stalin – as drawn by Cummings

Starting work on new collections is always fun. For a start it means you’re decreasing the number of items that need working on, but you also get to go through something that’s completely new to you. Most recently, I have started cataloguing artwork by cartoonist Michael Cummings, who worked mainly for the Daily Express for a period of nearly fifty years. This particular selection of artwork dates from the early 1950s, a time that seems to be far away in the past, at the beginnings of the Cold War.

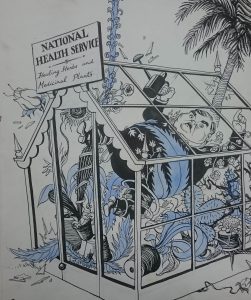

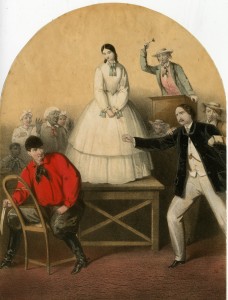

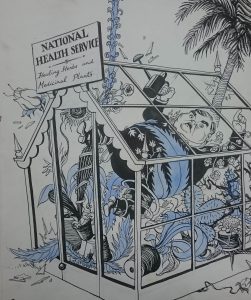

Now my first reaction was something along the lines of ‘oh no, I’m not going to know who anybody is’. As it turned out I was wrong. I recognized Clement Attlee, Winston Churchill and Stalin. This didn’t really give me a lot to go on. The 1950s are not exactly my strong point. I enjoy my history, but I enjoy my history quite a lot earlier than that. When I turned to the very first image and had literally no idea what was happening:

My first Cummings cartoon

My first reaction was, ‘this must be a Tory,’ based entirely on the caption. I had one other thing to go on, as somebody had very kindly written on the back of the artwork when the cartoon was published, and even what page it appeared on. As I knew all students and staff at Kent have access to UK Press Online, I decided to hop along and find the appropriate issue of the Daily Express. The cartoon was precisely where the artwork said it was, which was great. What was less great was the fact that there was nothing surrounding the image, no helpful arrows saying ‘this man is so-and-so’, and no articles relating to the image, as far as I could see, anywhere in the issue. So I hit a dead end. Extremely early on. Now what?

Well, perhaps unsurprisingly, Google searching ‘Conservative 1950s NHS’ didn’t get me very far. I had a look on Lexis Nexis but even narrowing down the date range produced more results to check than was feasible. I was almost on the verge of taking a photo on my phone and seeing if my Dad knew who it was, when I decided to check copies of the Express from the surrounding time period. This turned out to be the right thing to do – I came across a cartoon head of the very same man, this time with a caption telling me it was Aneurin Bevan.

Ok, so I basically got everything wrong. Bevan was a well-known Labour Politician, and at the time of the cartoon Minister of Health. At least I knew what the greenhouse was…

Getting the dimensions – featuring my tape measure, Colin

Establishing who people are in each of the cartoons is probably the hardest aspect of cataloguing them, for me. When I’m cataloguing I look out for specific information every time. First we need the basics: a title, artist, publication, date and size. Next comes recording anything that’s written in the cartoon, which we refer to as embedded text. This text and the image itself provides us with the information to assign subject matters to the item. This would be relevant political parties, or any celebrity and sporting news, or government policy mentioned. Other subjects can include setting, items or animals in the picture or emotions you think the people depicted are feeling. And then comes the time to add the people themselves to the record. This is also significant for the subjects; you can’t add the Chancellor of the Exchequer unless you know he’s actually in the picture.

When I first started cataloguing political cartoons, around two and half years ago now, I began with the more modern items. Part of our collections here at the British Cartoon Archive include the newspaper versions of cartoons that appear in the daily papers. This means our collection grows every day, and it’s partly my job to keep on top of this. I won’t pretend that I’ve ever had much of an interest in politics, (I knew next to nothing when I started), but I’ve definitely learnt a lot working here. I could at least recognise most of the Labour and Conservative politics, but my first big stumbling block was Danny Alexander. I think I found him by searching for ‘ginger Liberal politician.’

‘This is a Coalition Budget’ by Peter Brookes

In current cartoons, the colours actually plays a surprisingly large role in identifying who people are. It’s fairly obvious what party a politician is from based on what colour their tie is, (this is obviously a problem for women). This doesn’t work in artwork from the 1950s, which is done in black ink, with a blue wash which would appear grey in the published version. Another clue could be who the person is interacting with and how. If two politicians are having an argument about something it’s likely (although not definite) that they are from opposing parties. This also didn’t help me initially, as Aneurin Bevan was the only person in the first cartoon I catalogued, but it’s certainly helped along the way.

Once you get to know who someone is, there’s usually characteristics that most cartoonists exaggerate when they’re depicting them. For example, Theresa May is always wearing leopard print shoes, whilst Boris Johnson is mainly made of hair. Back in the 1950s, Winston Churchill always has a cigar. This wasn’t strictly speaking helpful, after all if you don’t know what Churchill looks like, where exactly have you been since the start of the 20th century?

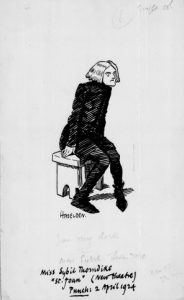

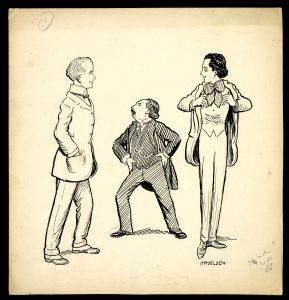

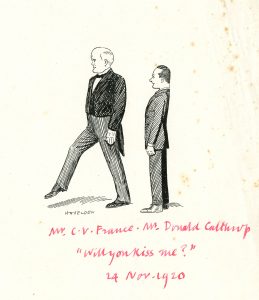

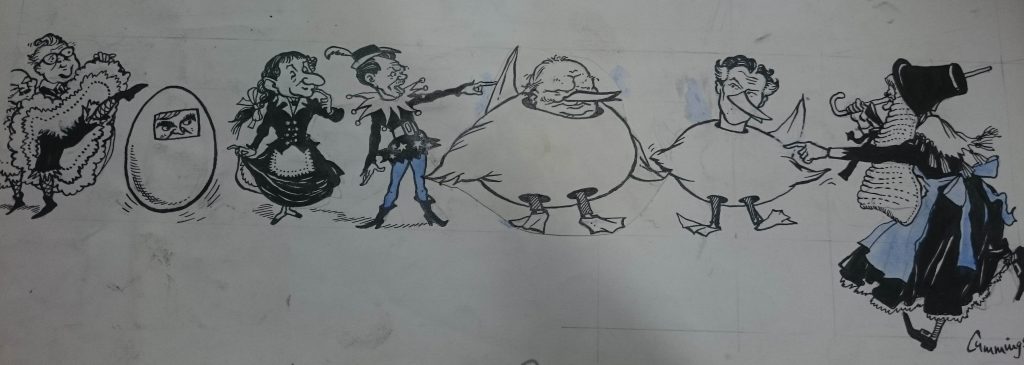

….and Strachey

Gaitskell…

Noses and eyebrows are also quite often notable. Aneurin Bevan always has large black eyebrows paired with his neat white hair. Emanuel Shinwell, (“Who on earth?” – me about a month ago), has a very prominent, bulbous nose. Unfortunately, John Strachey and Hugh Gaitskell seem to have the same long, pointy nose, so initially I had to check which hairstyle any pointy-nosed men had to establish who they are. Here the differences seem obvious, but when you don’t know who they are and their images aren’t next to each, it’s not so easy.

There is an odd enjoyment in all this hunting for people and discovering who they are, even though I often sit there in mild despair when all my methods have failed. I wonder if Poirot ever felt like that.

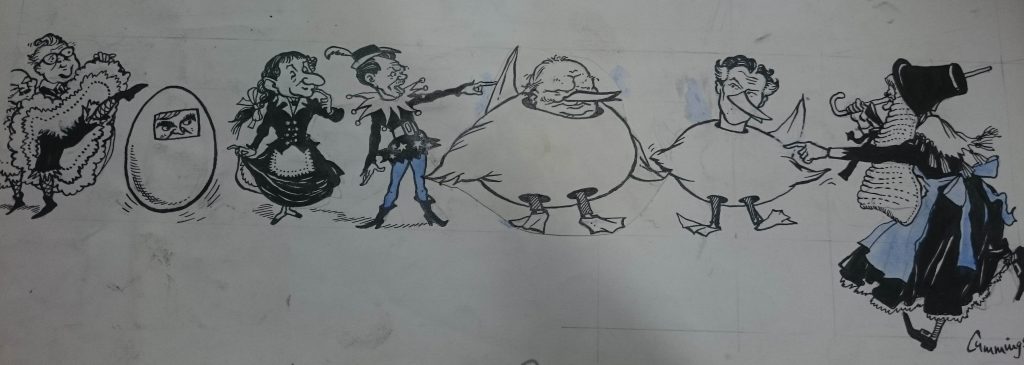

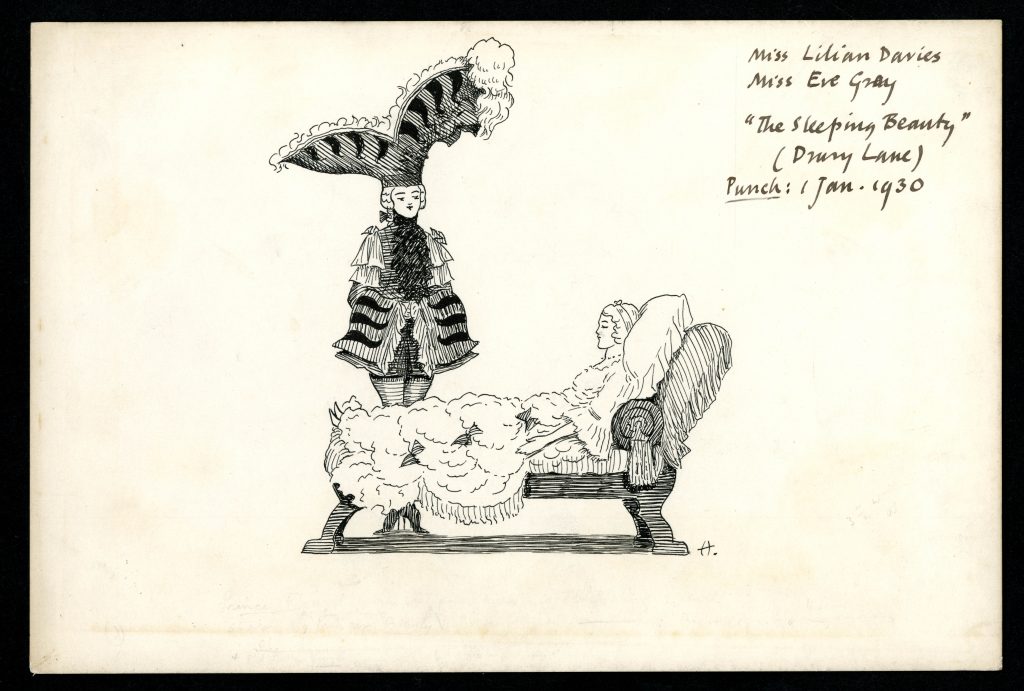

This brings us to my favourite Cummings cartoon:

‘The New Elizabethans’ by Cummings

I love this for two reasons. 1. It is genuinely a fabulous cartoon. I love the detail and the period costume. Elizabethans are much more my style. 2. The published version of the cartoon has a key that tells you who everyone in the picture is. That was a happy moment for me.

I’m going to let you all into a little secret now. One of the reasons I have particularly been enjoying my work with the Cummings Collection is that it’s a nice break from cataloguing the cartoons of today. Sometimes working on this kind of material can get a little wearing. Recently there’s been a lot of cartoons focusing on terror attacks, and a lot about Brexit and the US presidential elections, and for the most part these cartoons aren’t overly positive. This is because the cartoonists genuinely believe what they’re depicting, and the whole point of them is to draw your attention to things that they consider need changing. But it can get very repetetive, so the 1950s is like a little holiday in history for me.

Now obviously terrible things happened in the 1950s. The Korean War and the Cold War for a start, and Stalin certainly did some terrible things. But it’s strange how the distance of time can weaken the effects of this in the present day. If it wasn’t something you lived through, or even something your parents lived through, it’s very difficult to get a proper grasp on how it must have felt at the time. If it does affect you, then you know you’ve just come across a powerful cartoon.

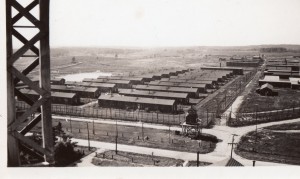

So far, this has happened to me only once whilst cataloguing this collection, when I came across the cartoon on the left. Published in early 1953, initially I didn’t have a lot to go on. It was obviously the shadow of a soldier, and that was enough for me to know if was referencing World War II. I don’t know how common this is generally, but in my head the 1950s and World War II are very, very separate. Even though I knew that 1953 was only eight years removed from the end of the war in Europe, and rationing was still ongoing. Even though I knew that war criminals were being tried, it never really occurred to me that this was something I would come across working on this collection. And that’s what this cartoon is depicting, the trial of men accused of taking part in the massacre of the village of Oradour.

For once the published cartoon actually stood alongside a relevant article in the newspaper, which allowed me to identify what it referenced easily. I had not heard of Oradour before, so I had to read the article to establish what exactly happened. I also used the internet to read more about it, and I was shaken. It wasn’t news to me that this sort of atrocity took place, but I wasn’t prepared for finding it amongst the cartoons.

I do think it’s extremely important that this cartoon, and others like it, exist. Sometimes images can convey more than words, particularly at a distance of seventy years, and cartoons certainly have their place amongst records of history, alongside sources like written accounts and photographs.

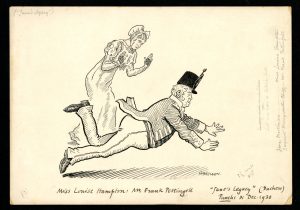

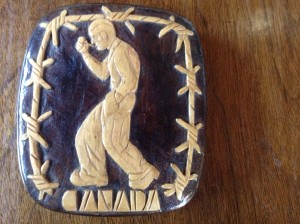

But it’s also important to keep things light. So here’s Churchill dressed as a goose:

A Politician’s Panto

All cartoons (c) Express Syndication Ltd, except Peter Brookes, (c) News UK

On the 12th October, the UK Philanthropy Archive hosted it’s second annual Shirley lecture, and first to be held in person on the University of Kent’s Canterbury campus. Following on from the success of last year’s online event where Dame Stephanie Shirley launched the series by talking about her life, and what has influenced and driven her philanthropy, this year saw Fran Perrin of the Indigo Trust speak on the importance of open data in the philanthropy sector.

On the 12th October, the UK Philanthropy Archive hosted it’s second annual Shirley lecture, and first to be held in person on the University of Kent’s Canterbury campus. Following on from the success of last year’s online event where Dame Stephanie Shirley launched the series by talking about her life, and what has influenced and driven her philanthropy, this year saw Fran Perrin of the Indigo Trust speak on the importance of open data in the philanthropy sector.