My name is Josie Caplehorne and I am currently working on a very exciting project in partnership with Rochester Cathedral to catalogue over 2000 of their rare books!

I have been a cataloguer since early 2013 when I began my role as a Metadata Assistant with the University of Kent. After a short time I began to work with the Special Collections & Archives teams to catalogue undiscovered materials, all the while continuing to undertake my day-to-day duties as a member of a growing team.

Excited conversations started to take place in the office (around mid 2014), that the University of Kent would work in association with Rochester Cathedral. This certainly caught my ear and I was very eager to be part of this. I had so far really enjoyed working with the university’s special collections, and was very excited about the opportunity to work with another rare, unique and culturally significant collection. In early 2015 I applied for the role of Rochester Cathedral cataloguer and, as you’ve probably worked out, I got the job!

Another rare book cataloguer was also recruited along with me and the collection will take us approximately six months to catalogue, with the work being undertaken at the University of Kent’s Templeman Library.

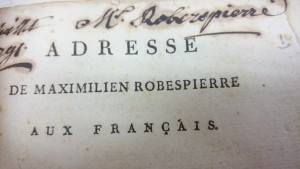

The collection is a fascinating one, and with the oldest book believed to be dated from 1498, the books I am cataloguing are rich in the history of the Church, Diocese and it’s Bishops.

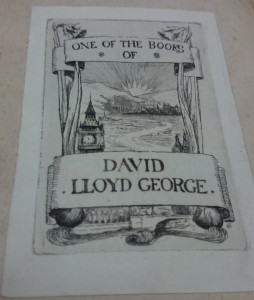

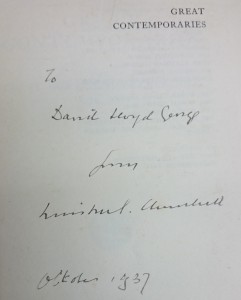

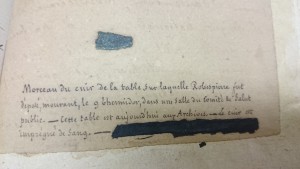

I am constantly fascinated by the journey the books themselves have taken through their long lifetimes, and with the presence of bookplates, handwritten inscriptions and letters held within the pages for hundreds of years, I feel like history is literally in my hands. I feel extremely fortunate to be involved in this work.

Once my colleague and I have finished the cataloguing, the collection will return to Rochester Cathedral Library. The library itself is currently being renovated to resemble its original form, where the books will be housed on handcrafted replica medieval wooden shelving. I am very much looking forward to visiting Rochester Cathedral in the future to see the books in a home that befits their history and beauty.

I look forward to telling you more about this collection as we uncover more of these fascinating books.