This series is now one of the longest serving on our blog; I wrote several posts ago that I hoped it would not take as long to reveal as the journey which William Harris undertook around Europe between 1821-1823. Well, I have a feeling that I may have already broken that record, but at least it’s given us all a sense of the length of time which this journey from Dover, through France to Italy and then to Sicily actually took!

William continued to number his letters for his father.

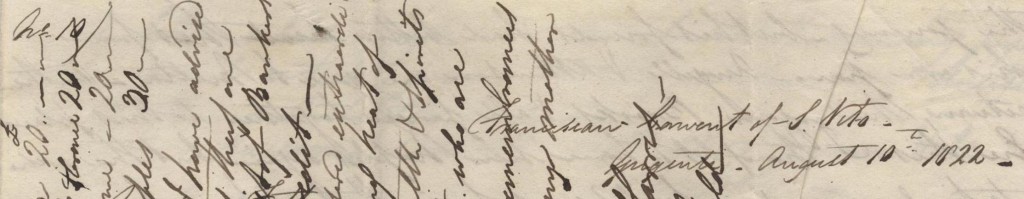

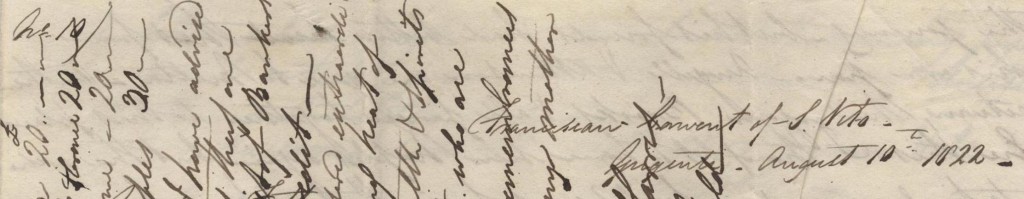

In the last post, William had just scaled Mount Etna with his band of architect friends, and found the undertaking rather easier than he had expected. By August 1822, however, William was lodging in the Franciscan convent of S. Vito, near ‘Grigenti’, alone. From my initial reading of this letter, I got the impression that William had been ill, but a second look shows little evidence of this. The group had intended to stay at a monastery before, at Taormina, but their plans were foiled when they discovered it to be full of priests awaiting the election of the new superior. So the fact that he was alone at a convent could simply be that it was a suitable location for his exploration of the ‘pure’ architectural remains of Sicily. In any case, perhaps he would not like to tell his father, so far away, that he was ill. After all, William Harris Snr., back in Norton Street, London, would wait months to receive the letter and then be unable to do much to help his son.

Of the remaining members of William Junr.’s group (two had left before the ascent of Etna), one certainly was ill: Brooks (who I described in an earlier post as the comedy partner) seems to have had bad sea sickness after the crossing from Catania. Thomas Angell and Mr. Atkinson were, however, made of sterner stuff, and had set out to explore Malta. William’s delight in the architectural remains in Sicily had been his reason, he told his father, for remaining alone. In any case, the friends were expecting to reunite, William thought, around the 21 August.

I suppose one of the other reasons why I suspect that all may not have been well with William is the brevity and directness of this letter. In the past, he had written very eloquent descriptions of places he and his friends had visited, and offered opinions on local habits. This letter, however, offers no description of his surroundings, nor of any of the ‘architectural’ (probably archaeological) sites which he visited.

William sent his letters home via his friend Mr Hunter, who lived in Paris.

Instead, the letter focuses on news from home, in London, which he had left more than a year earlier. We have already established that William’s mother did not enjoy the best of health; William considered that his parents’ removal to Peckham (at this time outside of London) would offer ‘cheerful society and a change of air’ which he was sure would be ‘very beneficial’. As well as his parents, William had a sister, Margaret, married to another architect, Thomas. In an earlier missive, he had learned that, for reasons of economy, they were removing from their home in order to let it. Because of this, he opens his letter having enclosed a letter for them, too, since he did not know where they could be reached. Again, the realities of the distance between William and his family, in terms of both time and miles, must have been playing on his mind. It had been 16 weeks prior to his sister’s letter since he had heard any news from ‘Old England’, having had no reply from his previous letter (no. 8, from Rome). Of course, he writes, his father may have replied to Naples, expecting William to be there, but the change in his plans meant at least a two month stay at Gingenti, rather than returning straight to Italy.

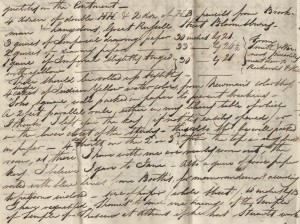

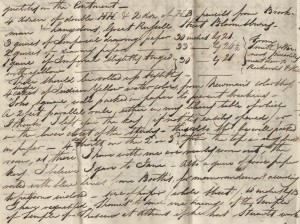

In spite of his desire to hear from home, time was obviously pressing: “As post time draws nigh I will now proceed to business and fill up the leisure if any remains afterwards”. This business consisted of a shopping list of materials and supplies, which William asked to be sent out to Sicily. Including pencils (from Brockman and Langdon’s, Bloomsbury), paper and watercolours, William explained that such drawing materials were ‘not to be obtained of even tolerable quality on the Continent’. Aside from these artists’ supplies for his sketching of classical ruins, William also requested that his father send out ‘a 2 feet parallel rule’, recalling that he had left it ‘either in my library table…or in the lower closet of the study’, paper ‘for memorandas’ and, from his brother-in-law Thomas, ‘tracings of the Temple of Theseus at Athens’. Finally, he asked for ‘4 day shirts…as those I have with me are nearly worn out.’ Unlike his friend Brooks, who had insisted on trunks of the latest fashions being sent out to Rome, William seems to largely have made do with that he had taken with him. Architecture and adventure seem to have been a much higher priority, for him, than clothes and supplies!

William’s shopping list.

This is the first instance of William requesting a significant amount of material from home, although he had previously mentioned in passing the cost of his travels, particularly his own frugality when living off his father’s allowance. Evidently, William had been able to spend some free time looking at his father’s responses, as he adds:

I now subjoin a list of the bills I have drawn on different bankers as they do not appear to agree with the memoranda you forwarded me

Lady Elizabeth Foster (1787), Duchess of Devonshire 1809-1824

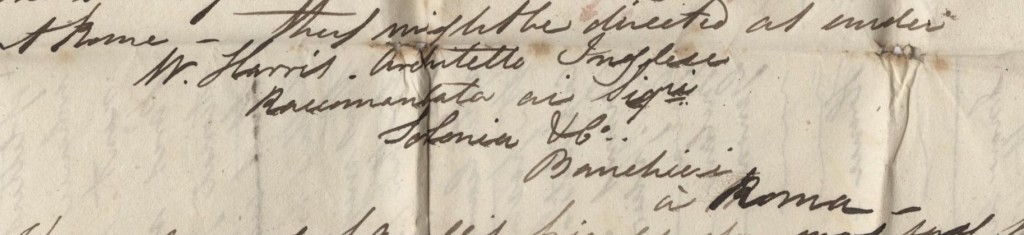

Although far from home, William clearly moved in circles of society which spanned the whole of Europe. Having previously visited contacts professional and personal, he asks for a letter of introduction from a mutual friend for the Duchess of Devonshire who was to stay in Rome over the winter. This was Elizabeth Christina Cavendish, who had married the fifth Duke of Devonshire, William Cavendish, in 1809 and retained the title of Duchess after the succession of his son to the title in 1811. The fifth Duke had been married to the celebrated Georgiana, but Elizabeth had lived with them since 1782, having separated from her husband Lord Foster, mystifying polite society. Elizabeth certainly had two children by the Duke prior to their marriage, and some whispered that she was lover to both the Duke and Duchess. In any case, she developed a love for the continent, even accompanying Georgiana during her exile designed to hide her illegitimate pregnancy from polite society. Following the death of the Duke, Elizabeth moved to Italy and developed an interest in antiquities, even financing the excavation of the Forum for eleven years. It is likely that this interest in classical architecture, and the circles in which she moved, were the main draw for William’s hopes of an introduction, but there must still have been a touch of scandal around this 65-year old widow as well.

The tone of this letter seems, to me, to be one of stocking up, preparing to start work again after a period of inactivity. Rather than tell his father about his exploits, as in previous letters, William is anxious to make sure he has the necessary materials to continue his adventure, but is also eager to hear more from home. He mentions ‘Jane’ once more, whom his father had removed from his house in the previous autumn, noting that he had given her the key to the drawer in which his shirts were kept. Perhaps the answer to this mystery is than Jane was a servant, presumably a long term and respected servant, since William had been sorry to hear of her departure. Thinking of home also led William to think of the horses: a favoured mount, Dick, had undergone an operation in the summer of 1821. ‘Pray let me know if Dick has recovered his lameness’, William writes in his closing paragraph.

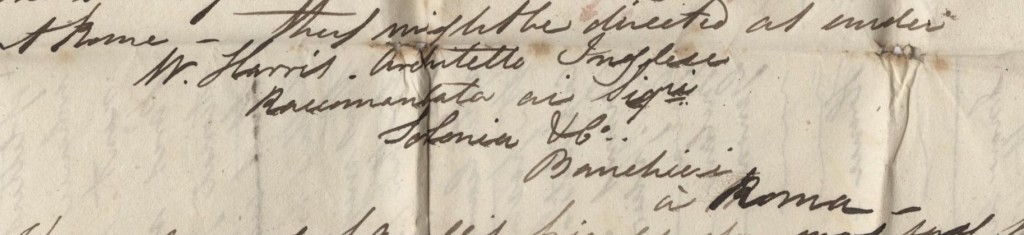

William had plenty of recourse to bankers during his trip – including to collect his post!

In spite of the time it took to journey around Europe in the early 19th century, it was evidently not an insurmountable exercise – at least not for those with the funds to support it. Postage, bankers and even letters of introduction to the seemingly web-like networks of society brought together like-minded individuals right across the Continent. But even with those modern developments, the distance from home could indeed feel great, and leave the intrepid traveller in danger of isolation. Yet William’s thirst for adventure took him still further in his discoveries – right into one of the biggest antiquarian scandals since the exploits of Thomas Bruce, seventh Earl of Elgin, at the beginning of the century.

A happy 2015 to you all; perhaps this year will see the closure of William Harris’ adventure!

To start with, on Tuesday this year’s student curated exhibition on Victorian and Edwardian Theatre was launched. This module has been running for 5 years, with each year bringing new and exciting developments, and an excellent exhibition as the final piece of work (and this year was no exception)! Throughout the term, second year students have been working with the Theatre Collections here at Kent, and digital collections available elsewhere, whilst learning about theatre between 1860-1910. For the final assessment, the students work in groups, picking a topic of their choice to explore and then present their findings as an exhibition, with an associated website.

To start with, on Tuesday this year’s student curated exhibition on Victorian and Edwardian Theatre was launched. This module has been running for 5 years, with each year bringing new and exciting developments, and an excellent exhibition as the final piece of work (and this year was no exception)! Throughout the term, second year students have been working with the Theatre Collections here at Kent, and digital collections available elsewhere, whilst learning about theatre between 1860-1910. For the final assessment, the students work in groups, picking a topic of their choice to explore and then present their findings as an exhibition, with an associated website. Tuesday turned out to be rather a busy day, since we were also hosting student book launches all day in the reading room. This was part of the third year Book Project module, in which students create their own, original piece of writing an publish it as a physical item. The launch event is a chance for the students to read sections from their work (in front of a supportive audience) and to sell copies to guests. We’re currently in the process of ensuring that we have copies of all of these works in Special Collections, to complement the twentieth century small print press materials in the Modern First Editions Collection.

Tuesday turned out to be rather a busy day, since we were also hosting student book launches all day in the reading room. This was part of the third year Book Project module, in which students create their own, original piece of writing an publish it as a physical item. The launch event is a chance for the students to read sections from their work (in front of a supportive audience) and to sell copies to guests. We’re currently in the process of ensuring that we have copies of all of these works in Special Collections, to complement the twentieth century small print press materials in the Modern First Editions Collection. A huge congratulations to all of the students involved in both of these exciting pieces of work: we hope you enjoyed being a part of it!

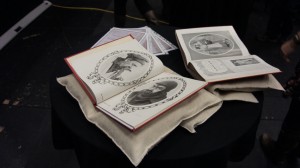

A huge congratulations to all of the students involved in both of these exciting pieces of work: we hope you enjoyed being a part of it! Cathedral Library, hosted by Cathedral Librarian Karen Brayshaw. Those who came along got to see rare and valuable books from the earliest years of the printing press through to the 19 century, including the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493) and a Bible translated into a Native American language. Alongside this, of course, we got to enjoy the ambiance of the historical library and its beautiful books – and several people enjoyed the smell of rare books!

Cathedral Library, hosted by Cathedral Librarian Karen Brayshaw. Those who came along got to see rare and valuable books from the earliest years of the printing press through to the 19 century, including the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493) and a Bible translated into a Native American language. Alongside this, of course, we got to enjoy the ambiance of the historical library and its beautiful books – and several people enjoyed the smell of rare books!