Yet again 2022 has been a year packed with activity and fun! We’ve seen a number of changes for the Special Collections and Archives team; adapting back to life on campus, welcoming new colleagues, fully reopening our Reading Room service post-pandemic, and embarking on new projects. We’ve also had a bumper year for volunteers, who have been working with our theatre collections, British Cartoon Archive, and medieval and early modern manuscripts.

As is tradition, it’s time for us to take a step back, reflect on what we’ve achieved, and tell you about some of the highlights…

Karen (Special Collections and Archives Manager)

It’s been an exciting year in special Collections and Archives. We’ve seen a number of changes in our team. In February we welcomed Beth Astridge to the role of University Archivist – you’ll recall that Beth was our project archivist for the UK Philanthropy Archive so it was exciting to be able to welcome her to a fulltime position. Beth has made her mark already in organising and delivering some excellent projects – you can read more about that in Beth’s section. We welcomed Rachel to our team on secondment from the Collections Management team. Rachel is working parttime as the project archivist for the UK Philanthropy Archive continuing the amazing work Beth was doing. In the spring we said goodbye to Jo, who worked as our Senior Library Assistant for almost a decade. Jo now has a fabulous job in London – though she still finds time to pop in and see us occasionally! In the summer we welcomed Christine in Jo’s place. Christine is now firmly established as our Special Collections and Archives Coordinator. Christine is doing a brilliant job of curating already established and new content for seminar groups as well as assisting with the research and selection for our latest exhibition 100 Years: T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land.

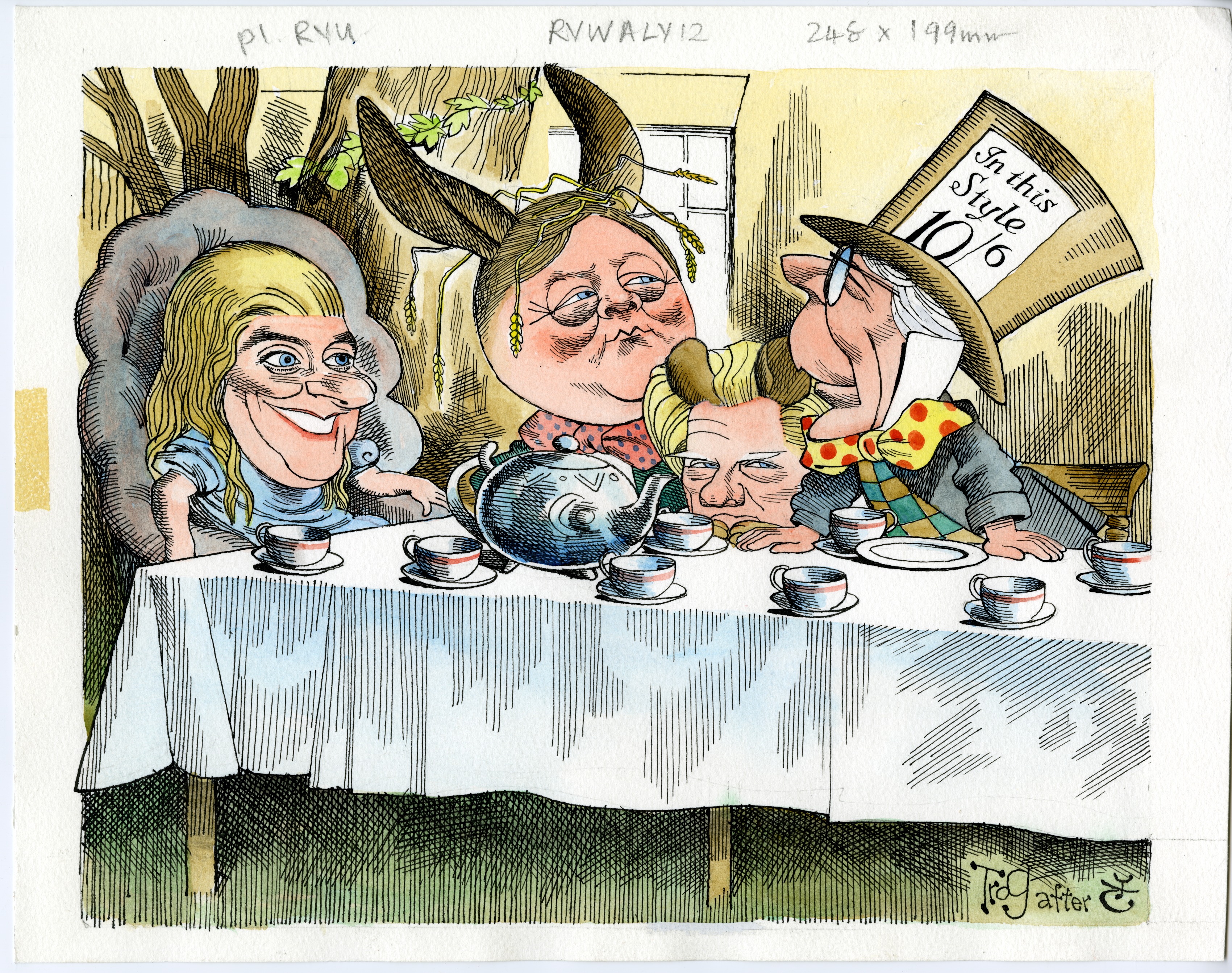

A poster advertising our Eliot exhibition, featuring a cartoon by John Jensen of Eliot in profile (JJ0584).

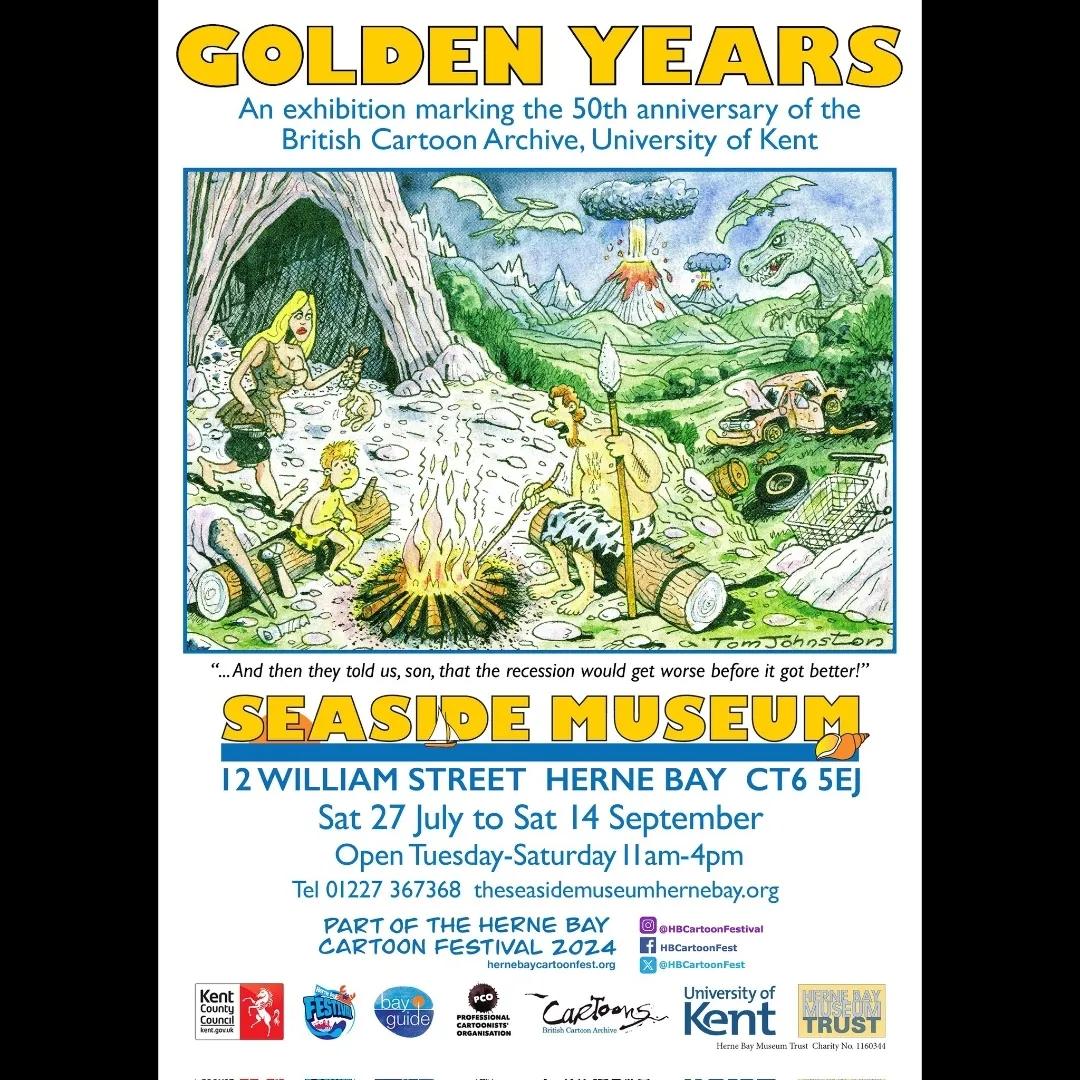

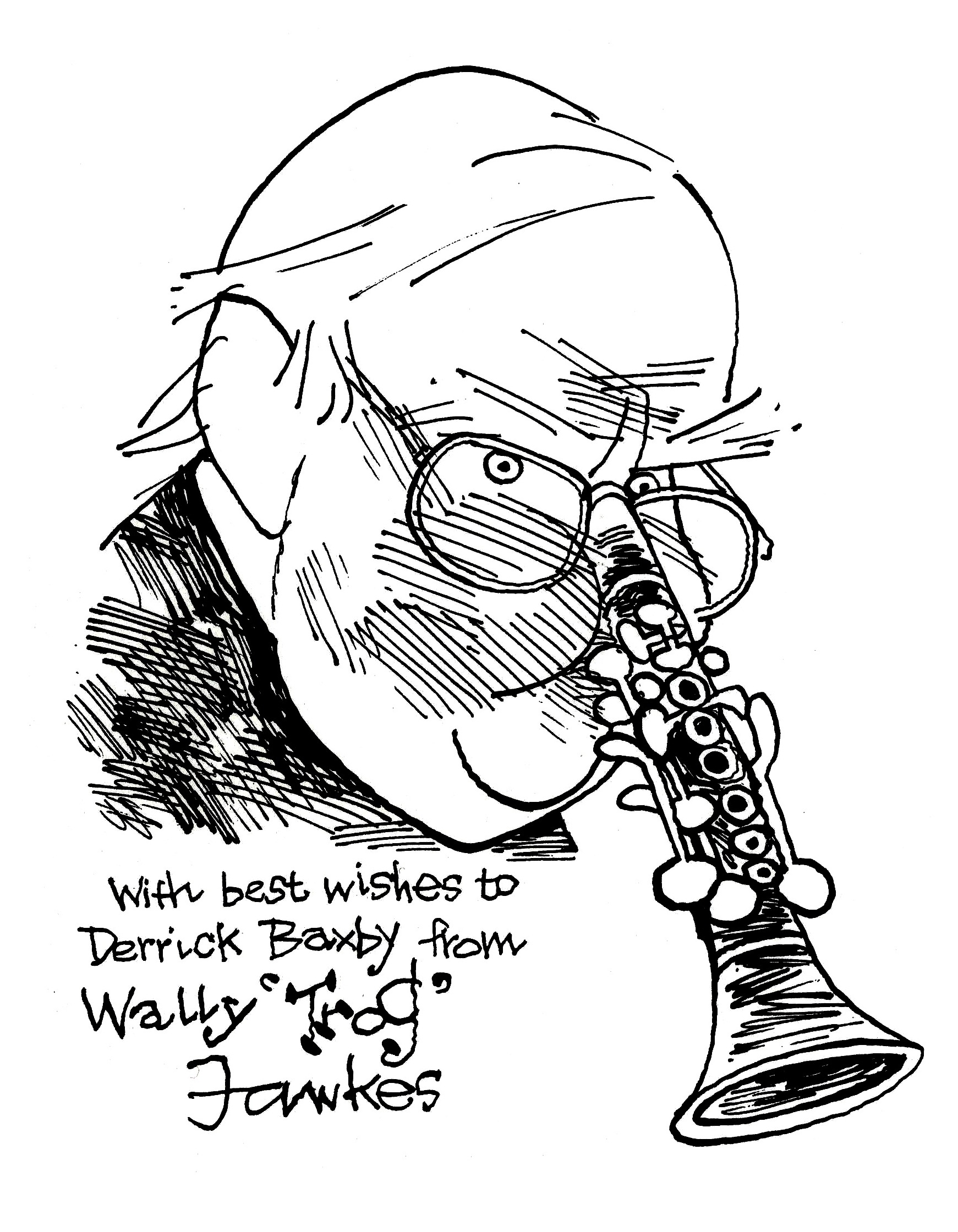

Clair and I had great fun meeting and working with Major and Mrs Holt to prepare their Bairnsfather Archive for addition the British Cartoon Archive – see Clair’s piece for a taste of what we have. We are also working on acquiring some other significant cartoon archives in the next year – which is especially thrilling as in 2023 we celebrate 50 years of Cartoons at Kent! Watch our social media for more details soon.

Mandy has been beavering away making sure our cuttings collection is kept up to date as well as digitising the beautiful photographs of Canterbury that we acquired a few years ago. You can see some in examples in Mandy’s section below.

Digitisation work has moved forward in a huge way this year. The Phase One kit is now fully functional and being put to good use – see what Alex and Matt have to say below for the latest from them.

We’ve also been lucky to tempt our former colleague Jacqueline back to the fold – Jacqueline has been working as a project cataloguer to get the books from Carl Giles Archive catalogued. Many of the books are now available on our online catalogue with more to follow in the New Year.

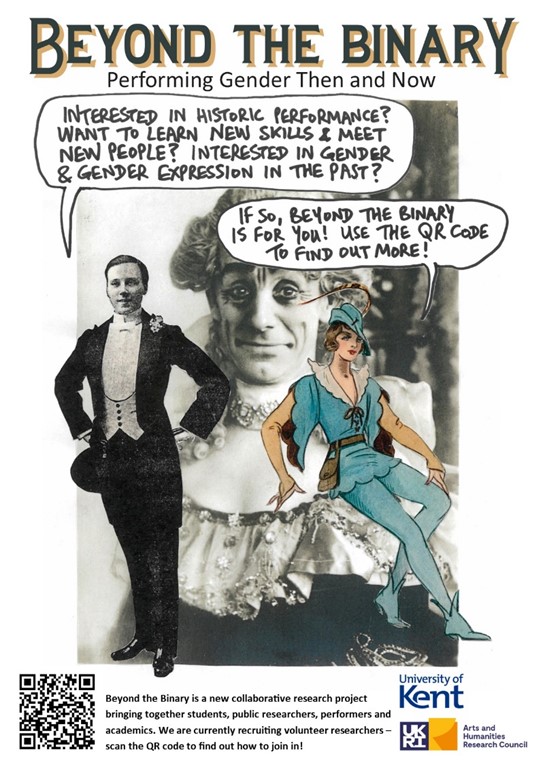

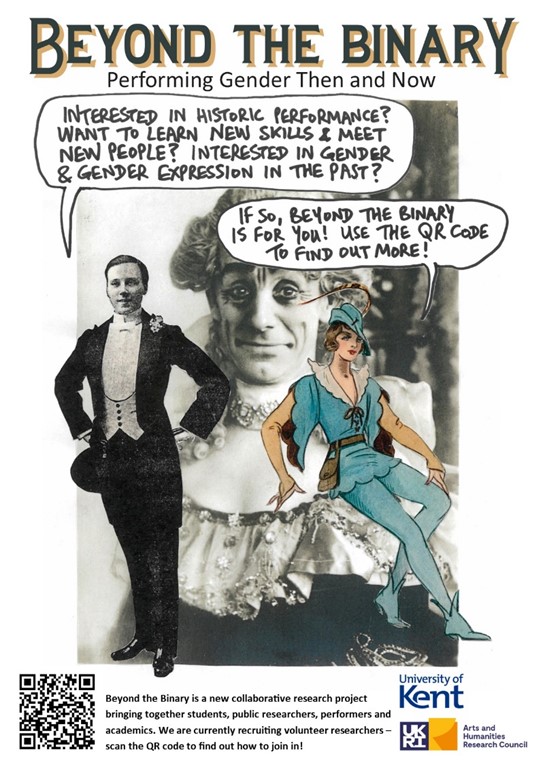

Earlier this year we received a small grant from UKRI AHRC to support some new collaborative research. We were delighted to work in partnership with our colleagues at the University’s School of Arts, Professor Helen Brooks and Dr Oliver Double, with Helen being primary investigator and Olly and myself acting as co-investigators. As a group, we were particularly interested in exploring representations of gender in popular performance, giving us the opportunity to contribute to the discourse on gender expression and new audiences with diverse, inclusive histories of performance and gender.

Poster for the ‘Beyond the Binary’ project

Beyond the Binary: Performing Gender Now and Then, brought together students, public researchers, performance-makers, archivists and academics from all backgrounds and from across the gender spectrum to undertake original research into our historic music hall and pantomime archives. They worked together on line to unearth histories of gender play and presentation hidden within the collections.

The research group also had the opportunity to spend a day in Special Collections and Archives and helped us to deliver a day at the Beaney Museum.

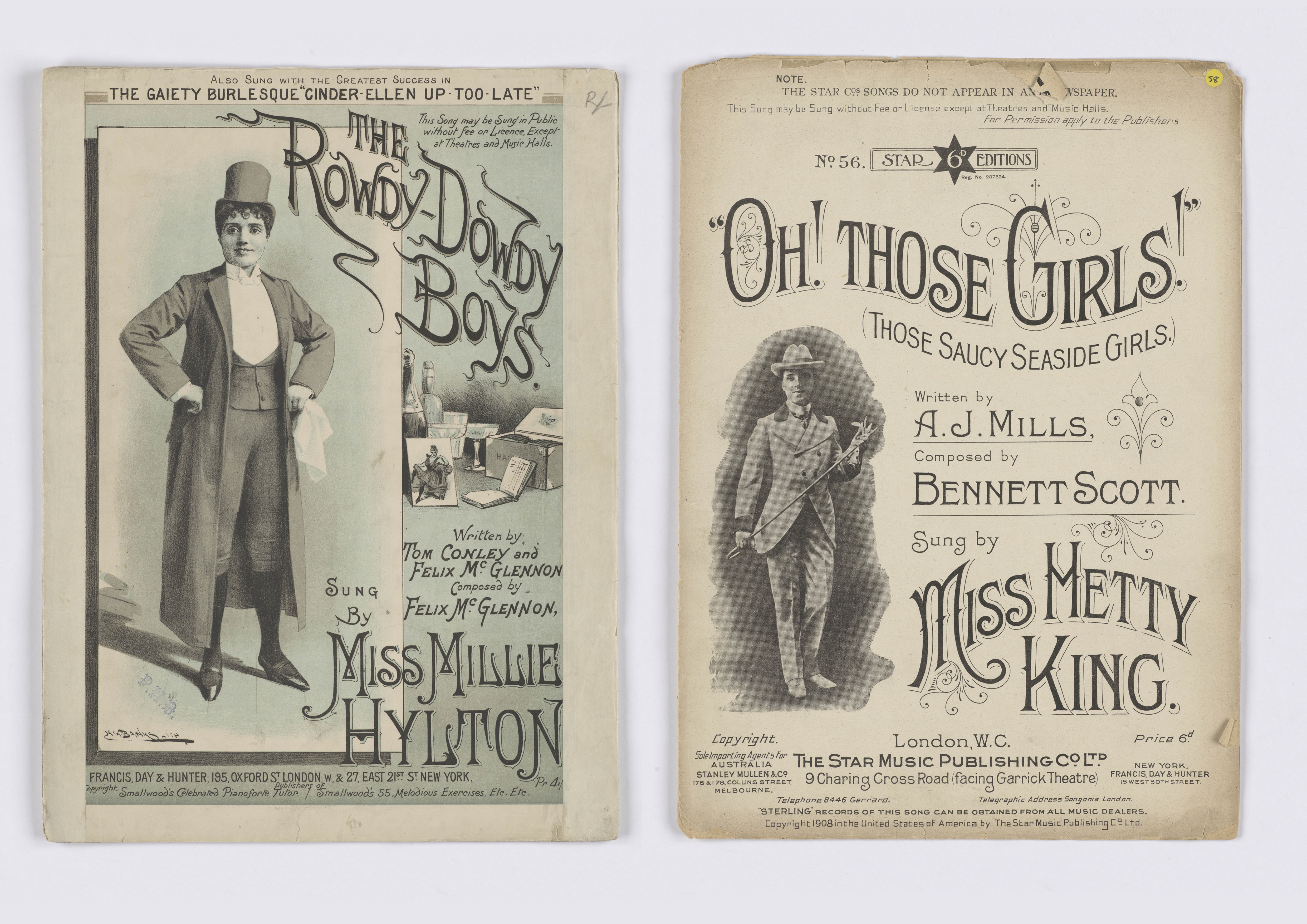

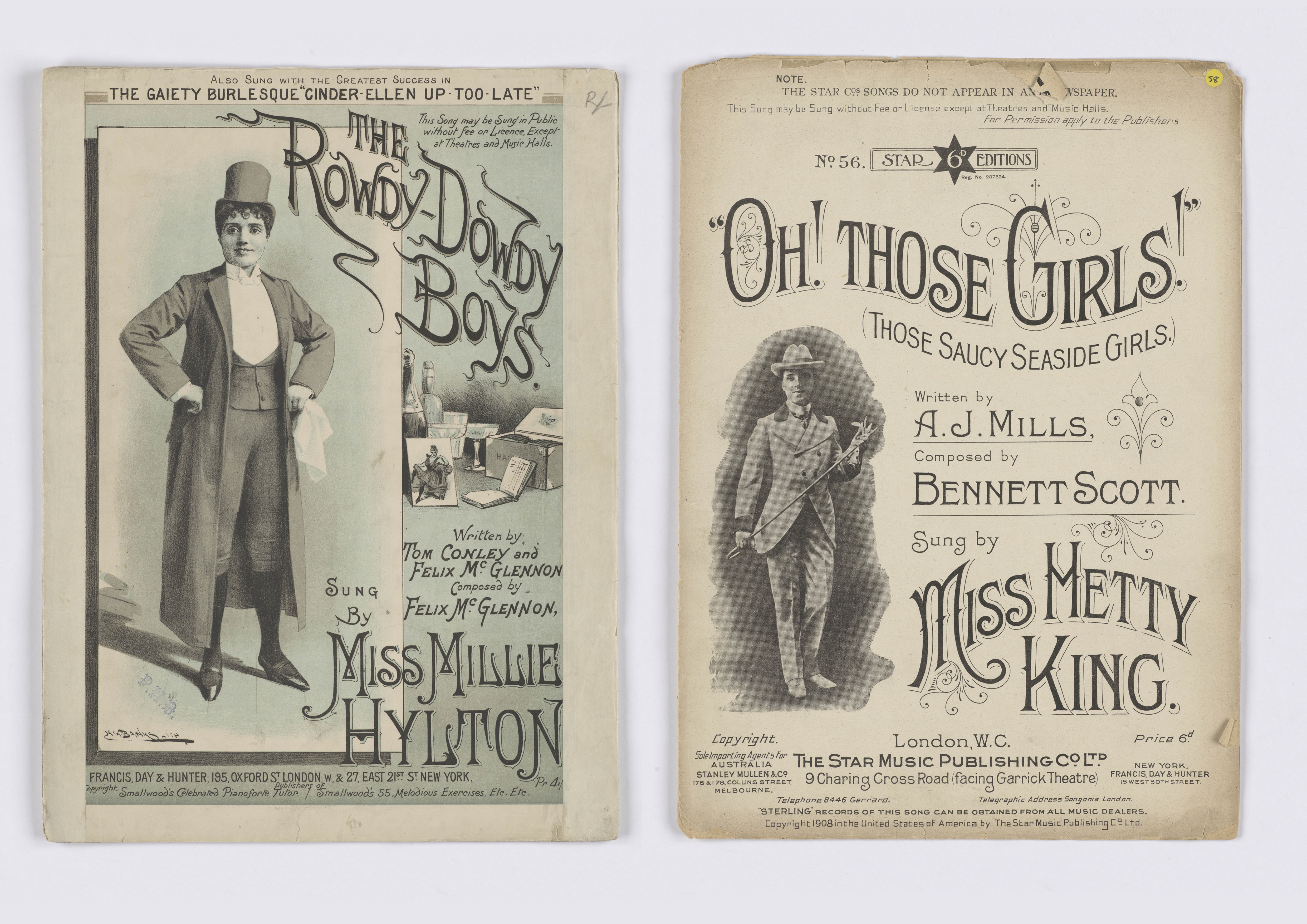

The final event of Beyond the Binary took place on Thursday 29 September, with a spectacular show, Rowdy Dowdy Boys and Saucy Seaside Girls at the Gulbenkian Arts Centre, Canterbury. The event brought together music, comedy and history. This new performance-lecture was co-created with non-binary folk performers, the Lunatraktors and featured comedian Mark Thomas. The Lunatraktors created new work inspired by items in the collection, which were displayed on a screen and on the stage – including comedy boobs, which were displayed on a specially made stand (adapted from a music stand) alongside one of the pantomime Dame costumes worn by Eddie Reindeer. Mark Thomas performed a hilarious piece he had written on the day – again inspired by the collections.

Two songsheets: Mille Hylton, ‘The rowdy Dowdy Boys’; Hetty King, ‘Oh! Those girls! (those saucy seaside girls)’

This year we were also delighted to succeed in our bid for the Archives Revealed Cataloguing Grants scheme. Our cataloguing project –Oh Yes It Is! – will be starting early in the New Year and will continue throughout 2023. The funding award will make an enormous difference in how we make the David Drummond Pantomime collection accessible to everyone. We will unlock its potential for researchers, historians, performers, and all those interested in the history of theatre and pantomime. We can’t wait to get started!

Some items from the David Drummond Pantomime Archive

Stop the Press! We’ve also just heard that in the New Year we will be receiving material from the first British Muslim pantomime Cinder’Aliyah. I can’t wait to share more news about it with you all when we have the details.

I think 2023 is also going to be filled with activity and fun!

Beth (University Archivist)

2022 has been my first year as University Archivist, as well as finishing off a few projects relating to the UK Philanthropy Archive, so there has been a lot going on!

Highlights of the work on our philanthropy collections include researching and installing the ‘Exploring Philanthropy’ exhibition which was up from April to November and allowed us to display items from the UK Philanthropy Archive for the first time and introduce visitors to the history of philanthropy; welcoming Fran Perrin to the University to deliver the second Shirley Lecture on open data and philanthropy; and presenting at the Association of Charitable Foundations conference in November 2022, alongside Felicity Wates (Director of the Wates Foundation) and Sufina Ahmad (Director of the John Ellerman Foundation) about the value of projects that reflect on the history of trusts and foundations with some ‘how to’ tips about dealing with your archive records. A lovely celebration to finish the year was that Dame Stephanie Shirley – the founder of our UK Philanthropy Archive – visited Canterbury to receive her honorary degree. It was my first Canterbury Cathedral gradation, and it was wonderful to experience it with Dame Stephanie!

Fran Perrin delivering the second Shirley Lecture, ‘Open Data and Philanthropy’

In University Archive work, I managed a team of amazing student interns who worked on a survey of the paintings, sculpture, photographs and other artworks on display in the College buildings. This survey led to some new acquisitions to the University Archive as we explored the Colleges! We located the archive records of Rutherford College and also some of the records relating to the early days of Darwin College. These have now been added to the University Archive collection and I’ll be looking at cataloguing the Eliot, Rutherford and Darwin College archive collections later in 2023.

We have put on some fantastic exhibitions this year which definitely deserve a mention in this summary. In June, with funding from the Migration and Movement Award Fund, we installed the exhibition ‘Reflections on the Great British Fish and Chips’ after working with a Research and Curation Group of volunteers, and our colleague Basma El Doukhi, who explored the collections and co-curated a display of original material looking at themes relating to migration, movement, global food production and the fishing industry.

The launch event for the ‘Fish and Chips’ exhibition.

With further funding from The National Archives’ Archives Testbed Fund we recently held a brilliant sensory event – Taste the Archive – where were hosted a food sharing viewing of the exhibition where we tasted fish and chips, falafel, ma’amoul, hummous and Arabic breads – all of which are featured in the exhibition. It was lovely to share food and learn more about other traditions and cultures in this sensory way.

The ‘Taste the Archive’ event

We ended the year with a new exhibition celebrating 100 years since the publication of TS Eliot’s The Waste Land. This is a great exhibition featuring some unique items from across the collections so come along and see it before April 2023!

Clair (Digital Archivist)

This year seems to have gone by so quickly; it’s a little hard to come to terms with the fact that we’re already writing our highlights of the year! Nevertheless, here we are in December.

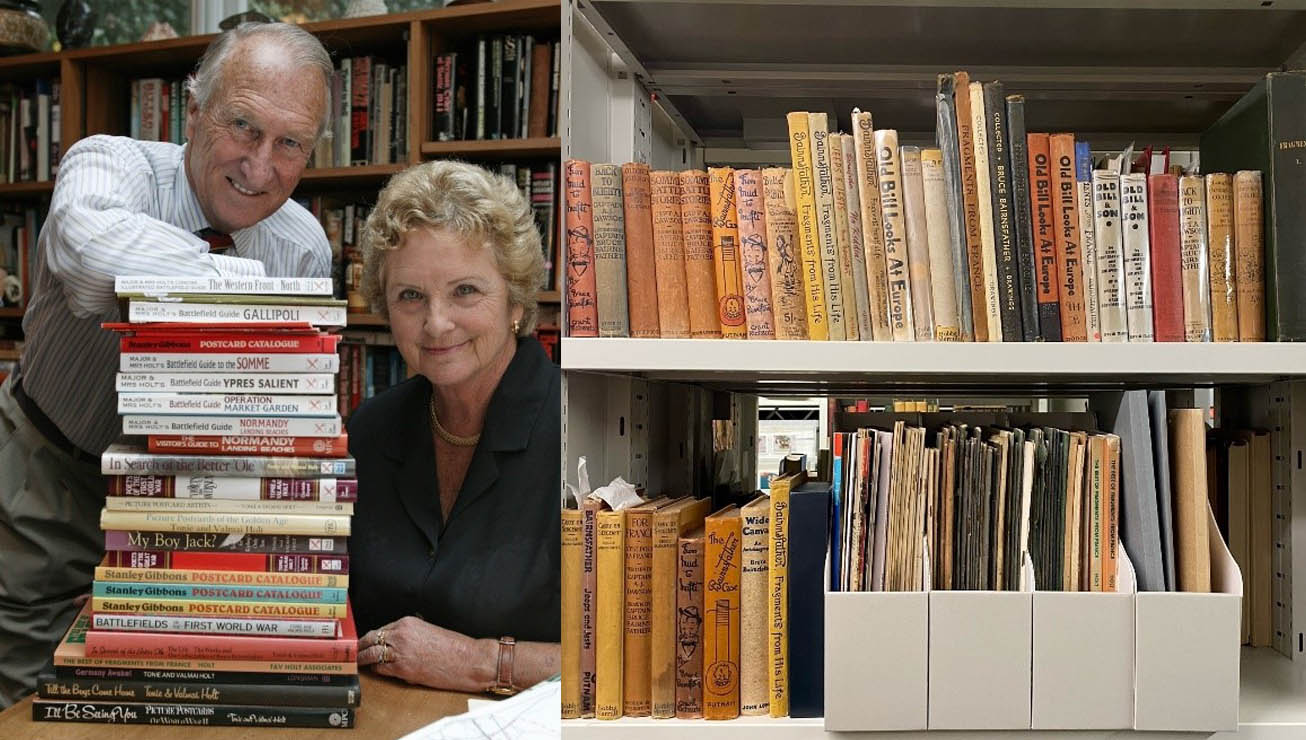

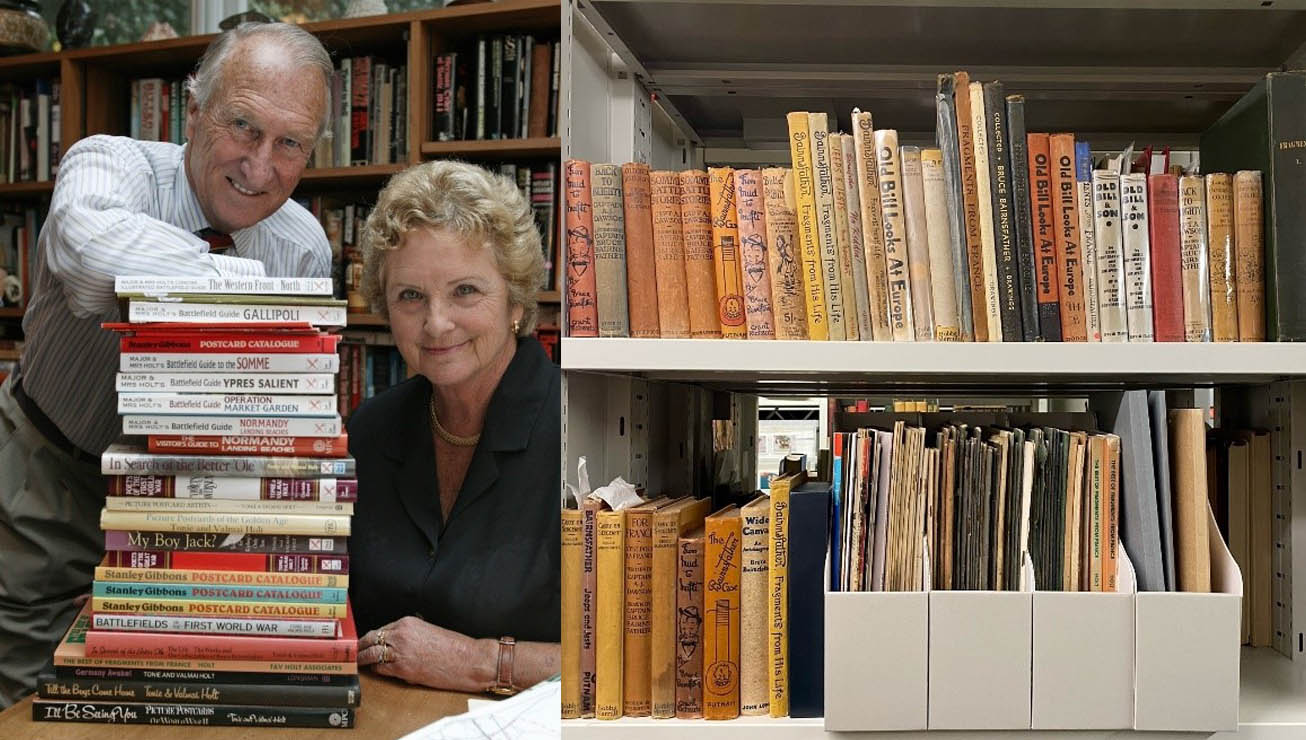

This year I had the pleasure of surveying and accessioning the Holt Bairnsfather Collection. Major Tonie and Mrs Valmai Holt are a couple who live in East Kent. They founded Major and Mrs Holts Battlefield Tours in 1978, offering tours to the public of famous battlefields across the world, before becoming authors. Together they have published over 30 books, including a biography of Bruce Bairnsfather. Their passion for Bairnsfather began in the 1970s, and since then they have amassed an extensive collection of Bairnsfather memorabilia, artworks and collectables.

Left: Major Tonie and Mrs Valmai Holt with their publications. Right: some publications from the Holt Bairnsfather Collection.

Tonie and Valmai welcomed Karen and I into their home to assess and survey the collection, before we listed and packaged it up for the archive. It includes pottery, china, books, journals and magazines, ephemera, metalware, sketches and artworks. An incredible collection, it really gives an insight in to the impact of Bairnsfather’s work and the popularity of Old Bill and the Better ‘Ole, even some 60+ years after his death.

A comparison of Bruce Bairnsfather’s ‘Well, if you knows of a better ‘ole, go to it’ (A Fragment from France, 24 November 1915) and Martin Rowson’s ‘Great War Studies – Module 8’ (Guardian, 06 Jan 2014. ©Martin Rowson, MRD0392)

We will continue to sort and organise the collection and hope to be able to add it to our catalogue in detail over the next year. 2023 brings the 50th anniversary of the British Cartoon Archive, and I’m sure this collection will play an important part in celebrating its continued value, and historic significance.

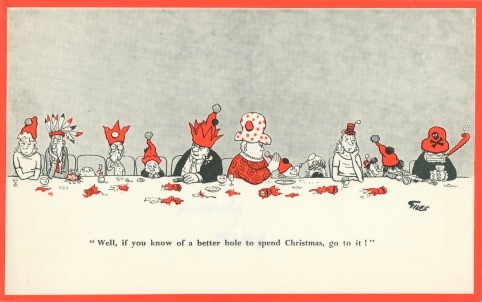

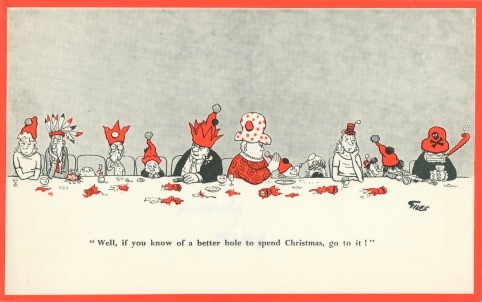

Ronald Carl Giles, ‘Well, if you know of a better hole to spend Christmas, go to it!’, Sunday Express, 1954. ©Express Syndication Ltd (GAC0102)

We’ve also made some positive steps this year towards improving our digital storage capacity and structure, after experiencing some challenges over the last few years with third party storage and disparate SAN locations. This work will have a real impact on our ability to continue to preserve and protect our digital and digitised collections in a robust and standardised way.

Christine (Special Collections and Archives Coordinator)

The greatest joy for me this year has been in planning and delivering diverse workshops in Special Collections and Archives to support graduate skills training and taught UG and PG modules. Over the course of 11 different sessions, I had the opportunity to meet and work with 135 students from the University of Kent and beyond, whose engagement with our materials established new insights and lines of enquiry.

Delving deeper into the archives of Monika Bobinska and Josie Long – two stand-up comedians and comedy club managers – I got to appreciate the home-spun and community-driven nature of their endeavours. These were/are truly pioneering women in their sector who cultivated emergent talent by emphasising inclusivity and creative freedom. Their clubs – respectively, the Meccano Club and the Lost Treasures of the Black Heart – provided space for experimental performance and audience participation. Just look at these charismatic felt audience contributions representing stops on the London Underground…

Creations that represent areas of London where audience members live (BSUCA/JL/2/6/4/4)

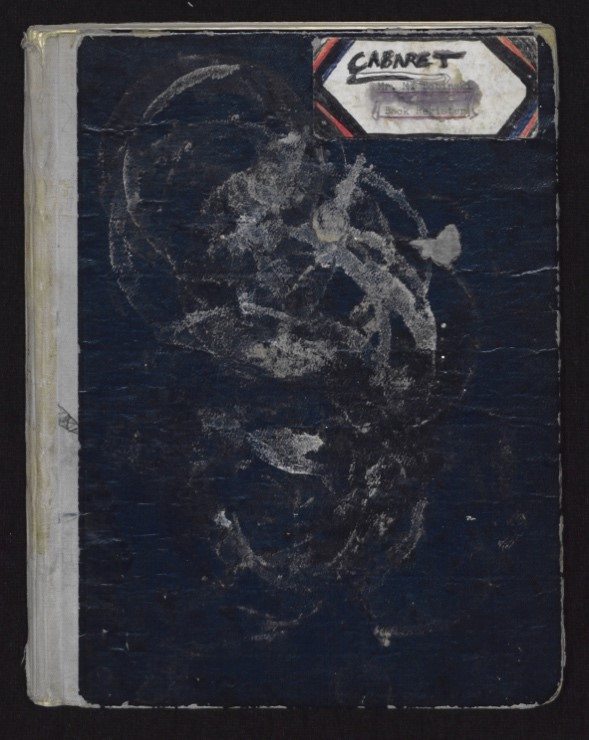

And this unassumingly pub-battered, pint-stained, contacts book that lists the crem de la crem of the alternative cabaret circuit – from Jo Brand to Mark Thomas.

A contact books for the Meccano Club with contacts for comedians, agents and venues (BSUCA/MB/1/1/6)

Another collection I’ve particularly enjoyed getting to know this term is our Modern Firsts Poetry collection, which boasts an astonishing variety of rare small press items and even unpublished proofs from British and American poets of the 20th century. Some of our wonderful volunteers have worked on repackaging this collection this term in order to better preserve the more delicate items – many of which are loose leaves, single sheets, or folded or bound in intriguing ways. This hands-on work has enabled us to not only improve our catalogue records and archival practice, but also to uncover some truly unique items. With examples that are at once abstract and incredibly tactile, this collection surely epitomises Modernist aesthetics and critical thought; ‘these fragments I have shored against my ruins’ testify, too, to the enduring legacy of T.S. Eliot – check out our current exhibition celebrating the centenary of The waste land!

Rachel (Project Archivist)

This year I moved into the role of project archivist for the UK Philanthropy Archive here at Kent, so a highlight for me was learning about the amazing collections we hold! This year saw us add two new collections to the Philanthropy Archive – those of the Wates Foundation and Craigmyle Fundraising Consultants.

The Wates Foundation archive is our first collection from a fully family run organisation. The organisation was first set up by three brothers, Allan, Norman and Ronald Wates. The Foundation has three family committees, one for each of the brothers, which means that the work they support is hugely varied. The archive contains project files for each organisation the Foundation has supported, ranging from city farms, to local sports teams, to crime and drug rehabilitation. There is also a wide range of literature and media outputs from these projects.

Four items from the Wates Foundation Archive

The Craigmyle Archive is a fascinating one, looking at philanthropy and fundraising from a different perspective from our other collections. Until now all our material has been from philanthropists themselves, whereas Craigmyle are professional fundraisers, working with charities and organisations who are looking to fundraise for projects. The company was founded in 1959, at a time where professional fundraising in the UK was basically non-existent. Their early focus was on supporting fundraising for schools, and there is a huge amount of material relating to all the work they have done in that area. The collection even has records of their work with other people who feature in our archive, such as Dame Stephanie Shirley, our founding donor! Clients supported by Craigmyle include Salisbury Cathedral, St. Paul’s School for Boys, Macmillan Cancer Relief, Kingston Theatre Trust and The Woodland Trust, to name just a few. This is by far the biggest collection the Philanthropy Archive has taken in yet, and a dedicated archivist will be being employed to work with it next year, so watch this space!

Outside of the collections, my highlight for this year has definitely been attending the degree congregation at Canterbury Cathedral last month where the University of Kent awarded Dame Stephanie Shirley an honorary degree.

A photograph from the graduation ceremony. Left to right: Dr Beth Breeze, Dame Stephanie Shirley, Rachel Dickinson, Beth Astridge.

I graduated from Kent in 2012, but this was my first time seeing a ceremony from the other side. Canterbury Cathedral is such a lovely setting for a graduation ceremony, it feels appropriately grand for recognising all the work put in by our students to achieve their degrees. This was also my first time meeting Dame Stephanie in person. We discovered it was honorary degree number 31 for her, but she was still incredibly grateful for the recognition and genuinely had a wonderful time in a glorious setting. The speech she gave referenced her support of the University, including her ties to our archive and her work with the Tizard Centre, and her message to all our graduands was heartfelt and really well received.

Matt (Digitisation Manager)

As Alex has alluded to below, after the install and learning phase of 2021, 2022 has been the year of the Phase One. It’s made a huge difference to our digitisation abilities as we’ve learnt to make the most of the whole system. As we progress with our pre-planned projects we’ve started to consider what it can do for us in the next years and the other collections we can digitise. When looking at collections we’ve had for years it’s exciting to have a new perspective on them now that we can digitise them in such amazing detail.

We’ve also spent some time in the last few months refurbishing a new space for our digitisation systems so that we can bring it all into one custom space, (and also so that we can finally relinquish half of the Special Collections work room back to our colleagues). We’ll be moving in at the start of next year.

Our new digitisation space in the Templeman Library

Earlier in the year we completed a project assessing our preservation and access systems for our digital collections which means next year we can move forward into testing and hopefully acquiring a new system that will mark a significant step forward in our digital offering to users of our various services.

Mandy (Special Collections and Archives Assistant)

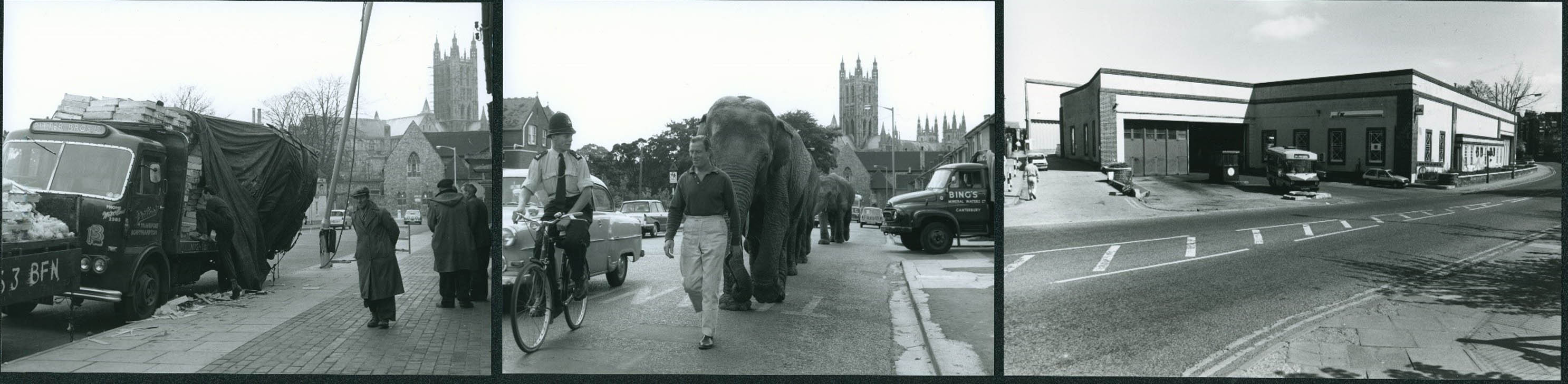

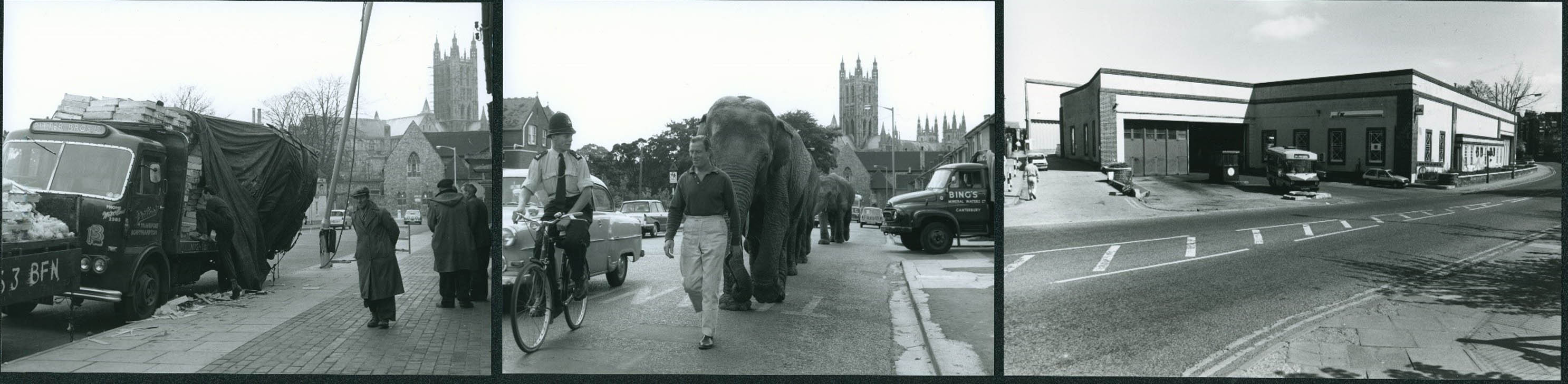

Here are a few photos that I have been lucky enough to scan over this past year.

Three photographs from the Crampton Canterbury Photograph Collection

They are from our Crampton Canterbury Photograph Collection, and show how much Canterbury has changed throughout the years.

Alex (Digitisation Administrator)

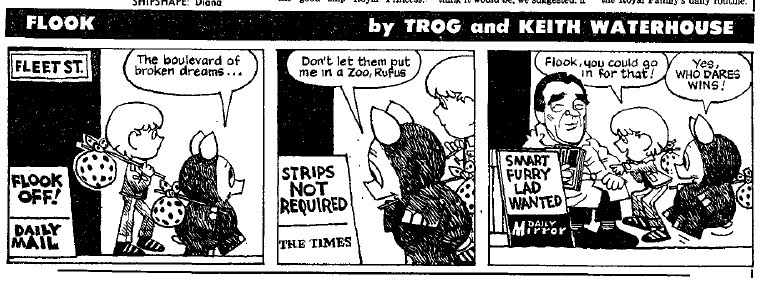

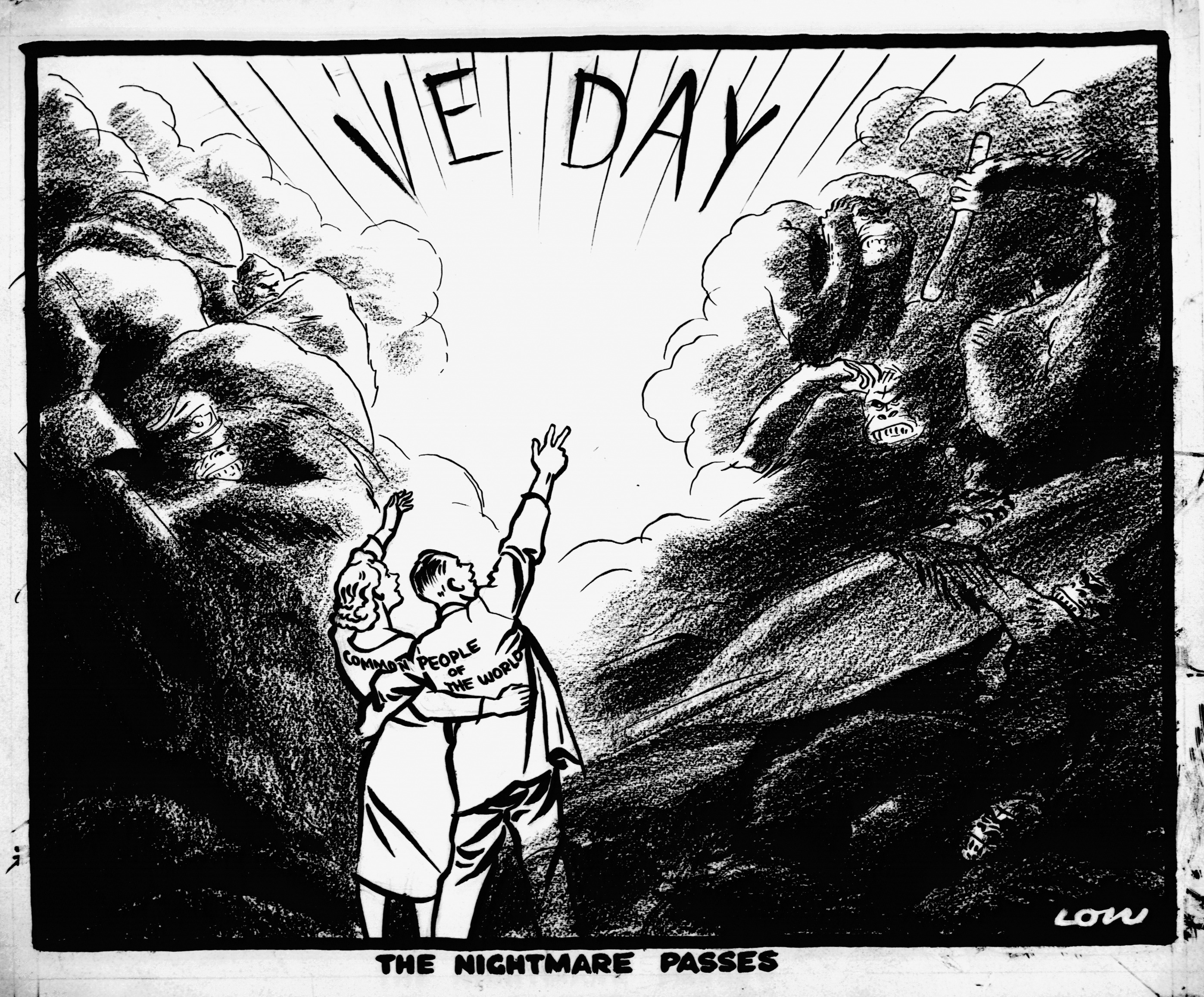

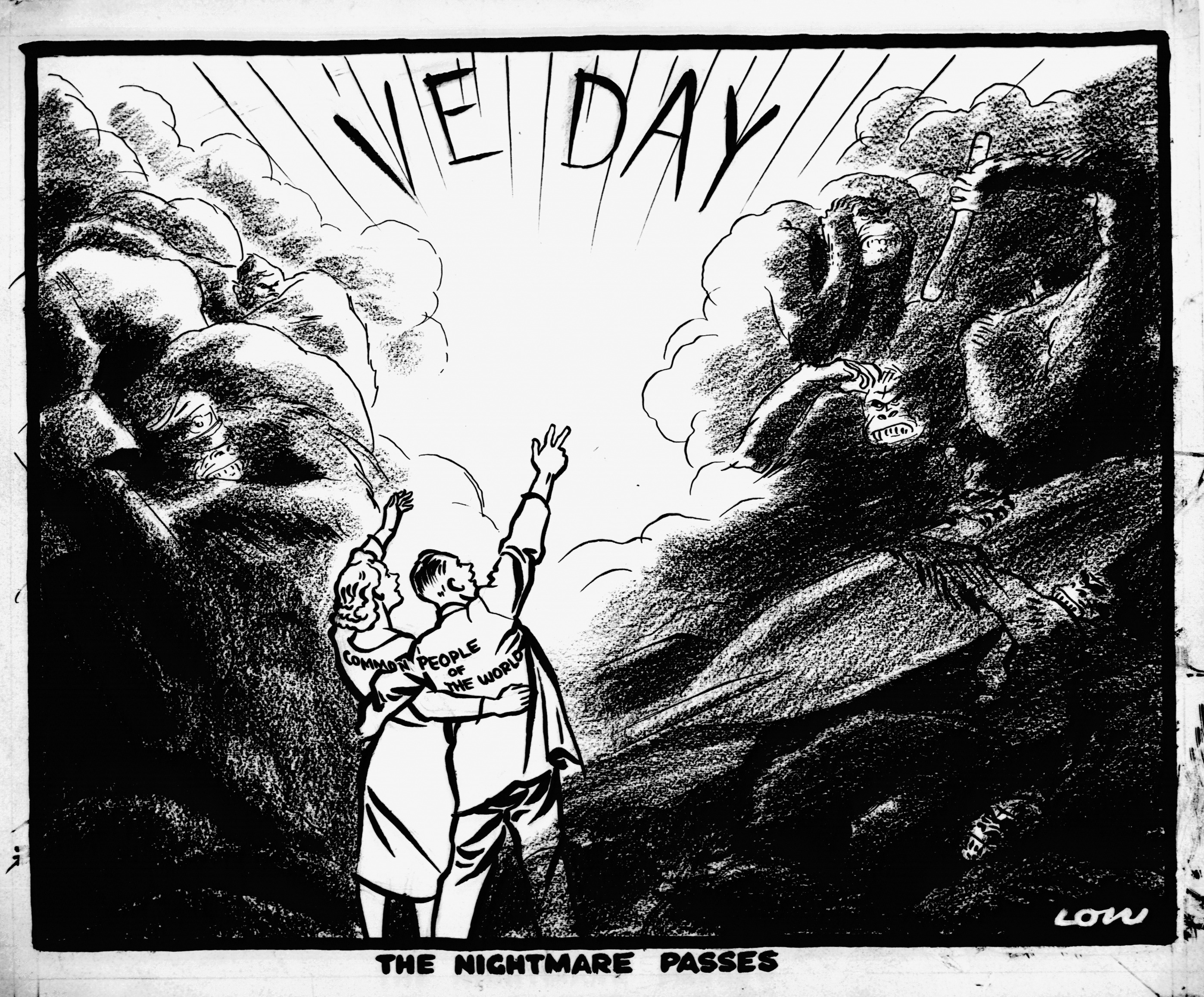

2022 has seen the new Phase One photographic reproduction rig come into its own. Alongside colleagues Matt and Clair we developed efficient work processes for the digitisation of artwork and objects within the collections. Once we had the rig up and running in early February the main focus has been on the Beaverbrook Collection of cartoon artwork. The Beaverbrook collection is significant, containing original cartoon artwork by major cartoonists published in some of Britain’s leading newspapers from the 1930s through to the 1960s. To date we have captured around half of the entire collection, over 4000 high-definition images. I’ve found it a fascinating process, particularly the insight it provides to the day to day “talking points” during a turbulent period of global history.

A David Low cartoon from the Beaverbrook Collection, ‘The Nightmare Passes’, Evening Standard, 8th May 1945 (DL2416)

In the audio-visual domain, I completed the digitisation the University of Kent Archive collection of vulnerable analogue magnetic audio cassette tape recordings in the first part of 2022. Since then, I have moved on to digitise of a number of smaller audio cassette collections within the greater Special Collections and Archives stores. These have included recordings from the British Stand Up Comedy Archive, the Ronald Baldwin local history collection and the R. W. Richardson collection of recordings relating to the 1980s Miners’ Strike, particularly in East Kent.

One of the many audio cassettes Alex has digitised this year!

Most recently I have been digitising a series of interview recordings carried out by the University’s Dr Philip Boobbyer. The interviews were conducted during the 1990s in post-Soviet Russia. The subjects of the interviews were various activists and dissidents from the Soviet period. The content has particular contemporary relevance in light of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

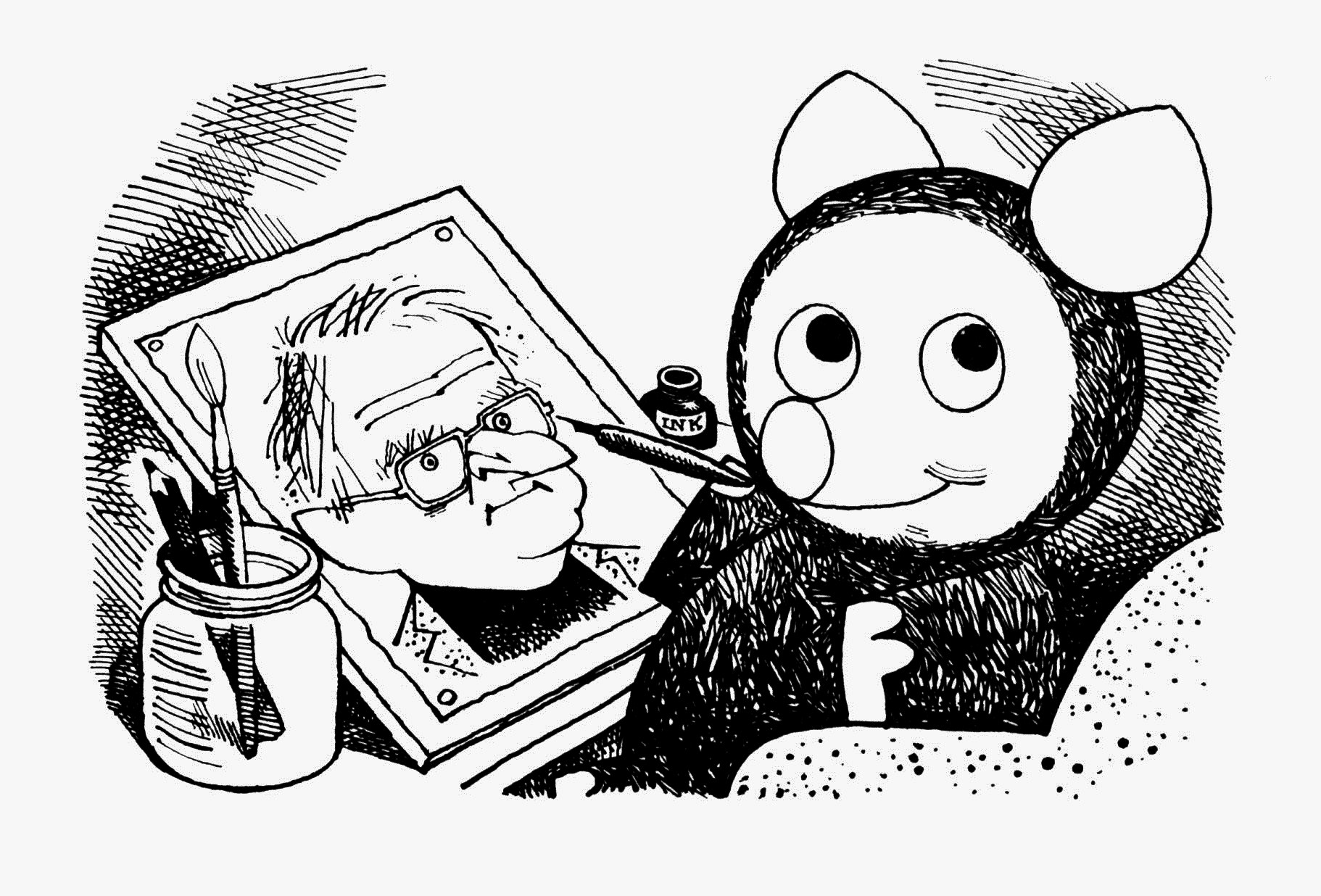

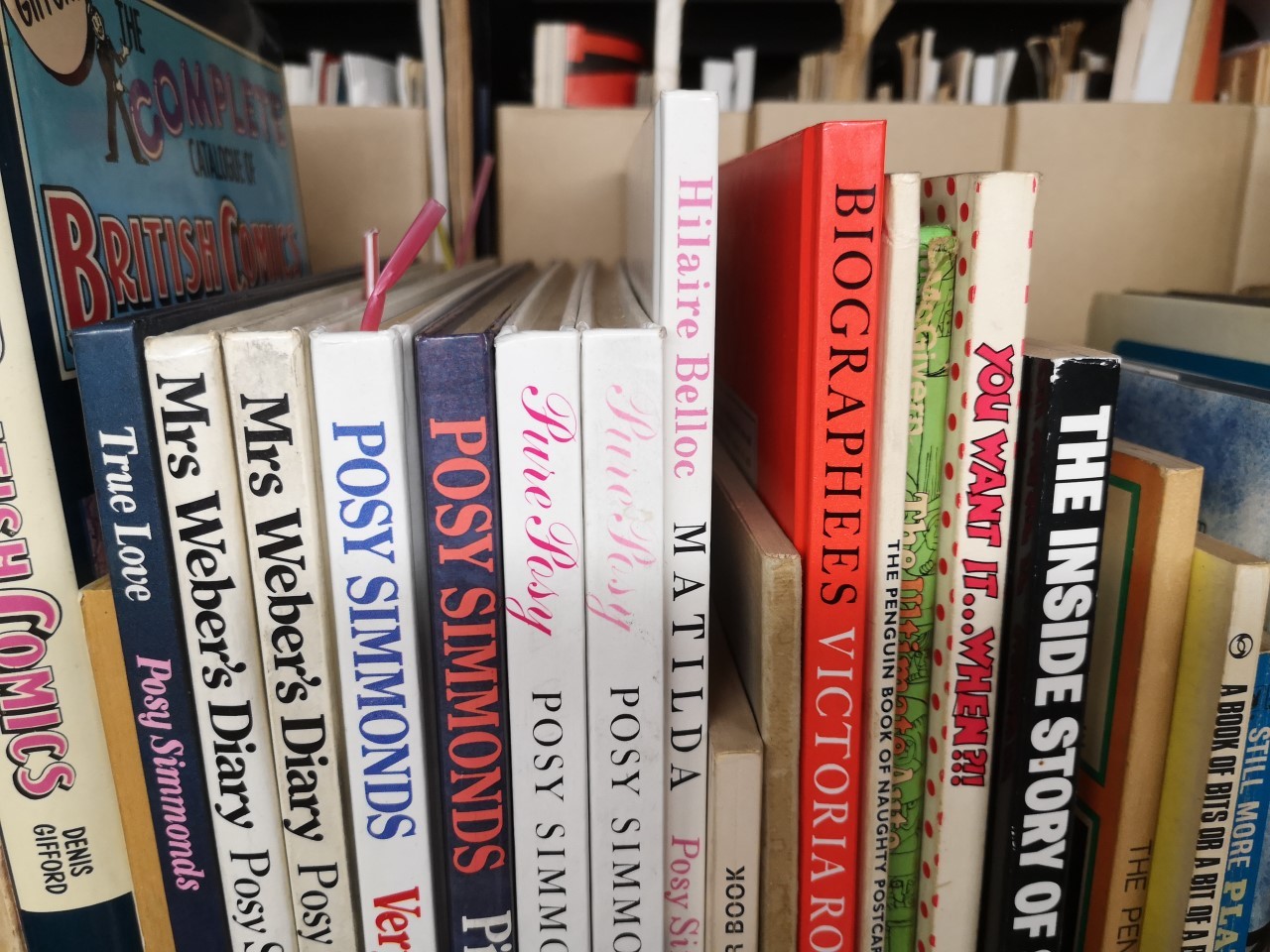

Jacqueline (Project cataloguer)

I am cataloguing the personal library of Giles the cartoonist kept within his archive in the British Cartoon Archive. The library shows Giles’s distinctive set of interests reflecting both his work as a cartoonist and home life near Ipswich in Suffolk. He indexed books with coloured drinking straws to mark images that he might use as references. His collection of works of cartoons from the two world wars, together with contemporary photographic books give a poignant insight into lived experience of those events.

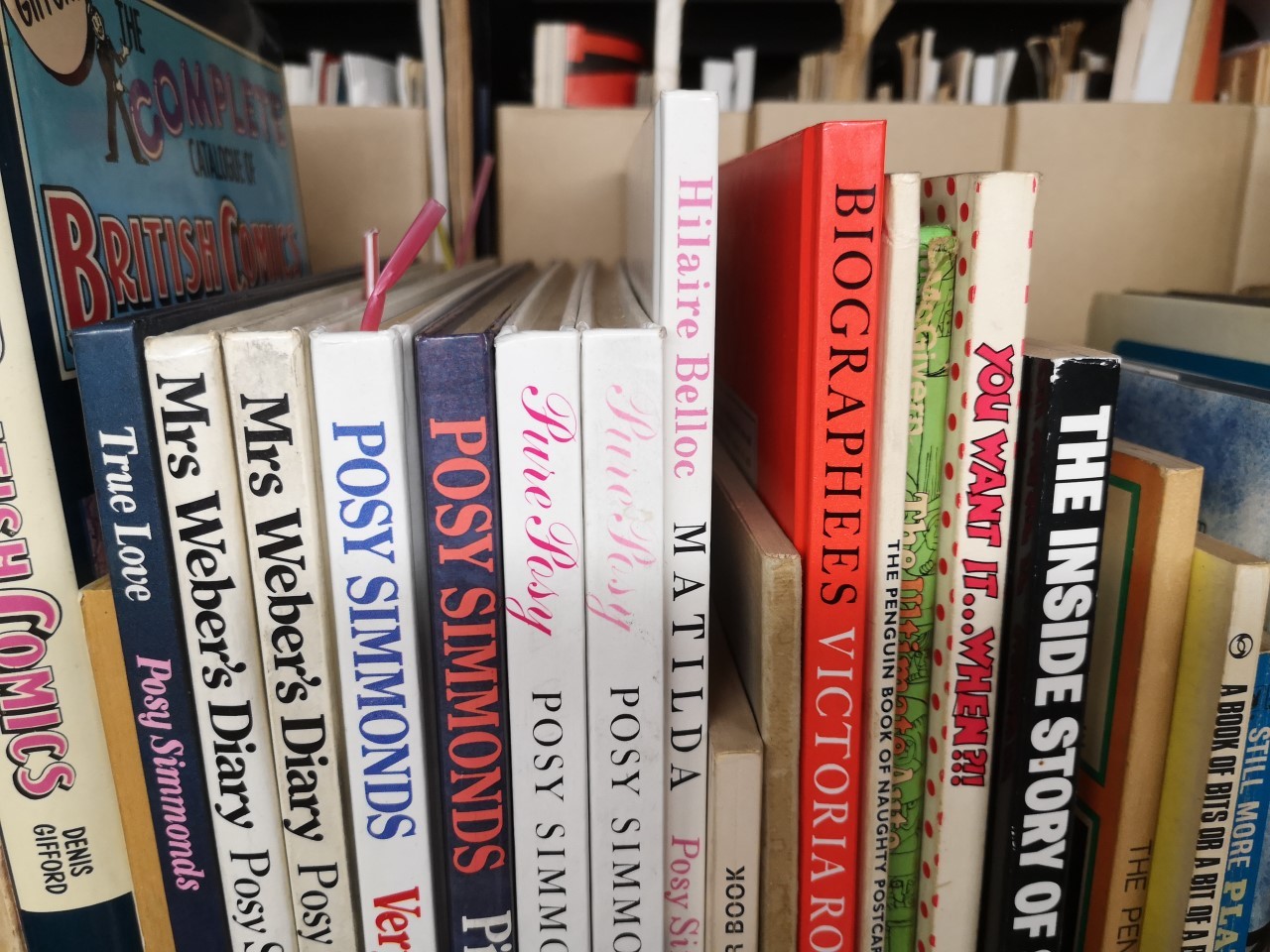

An image of books from the Giles library

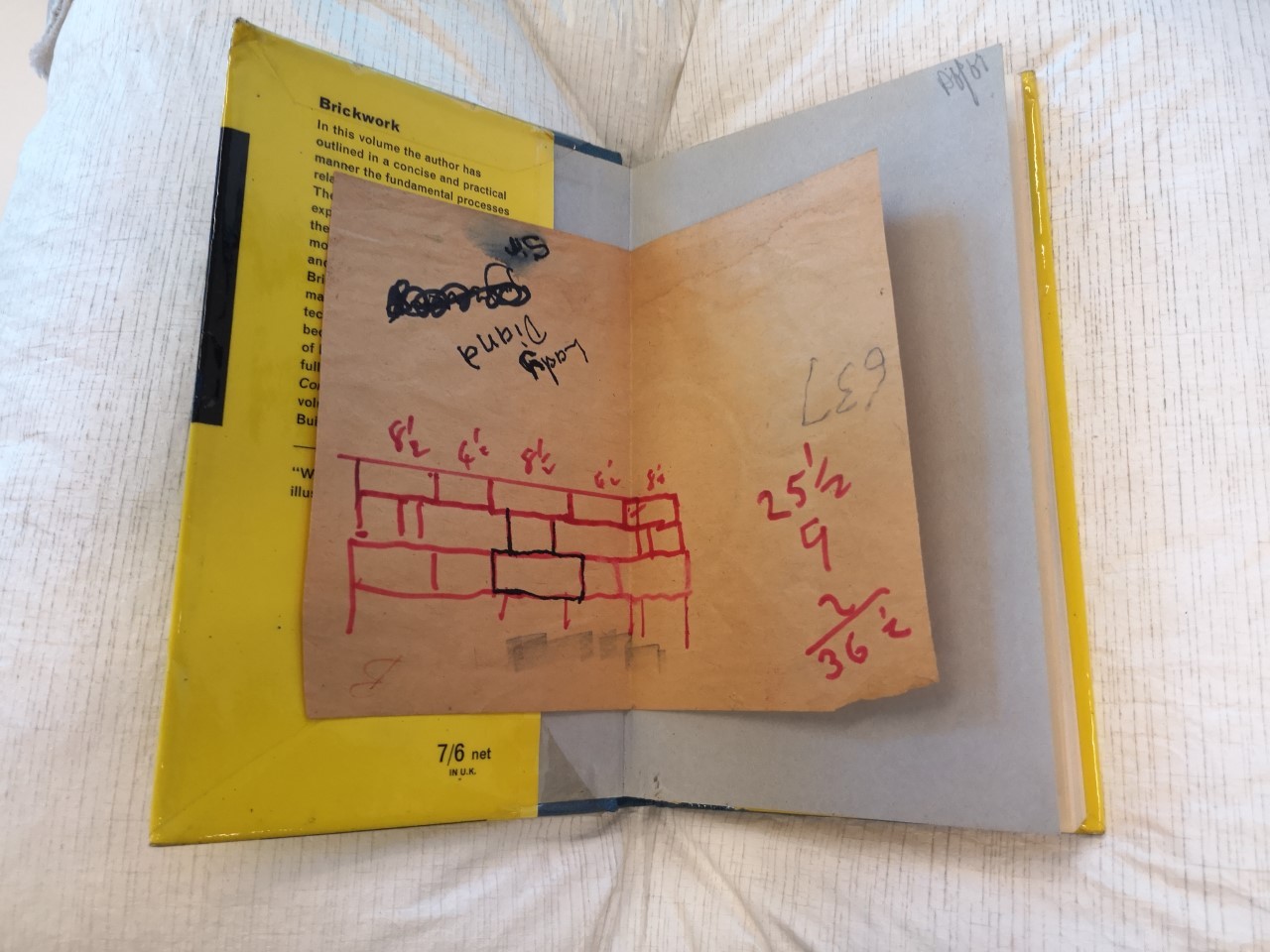

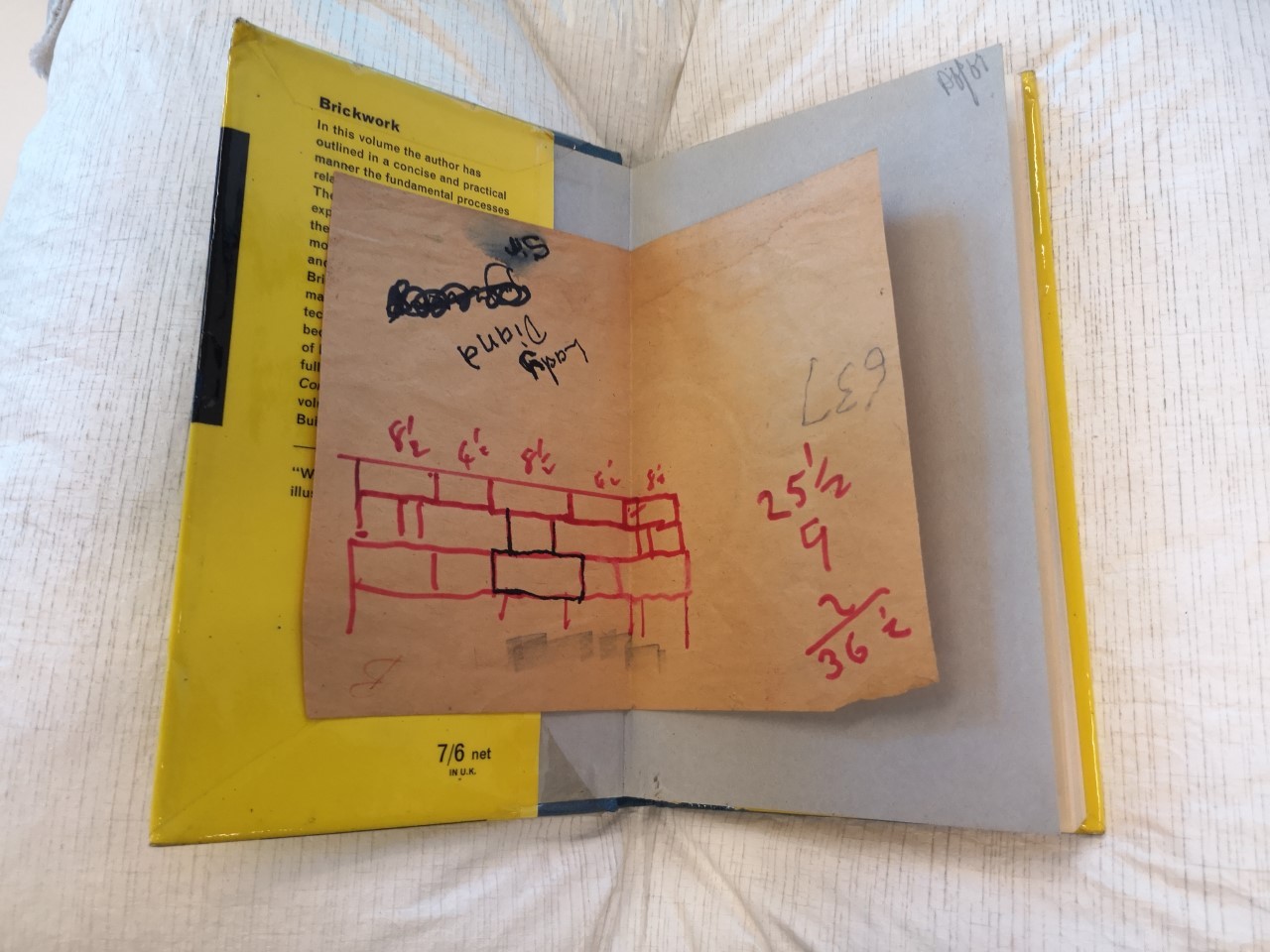

There are sections on farming, on architecture, sailing and ships and series of how to draw books, I-Spy books and even an Argos catalogue. The mix of ideas for cartoons and his everyday life appears here in his copy of ‘Teach yourself brickwork’ with “Lady Diana” written the other way up on his plan for a brick wall with measurements inside the front cover.

An image of the inside of ‘Teach yourself brickwork’ with an inserted note inside